Last week I wrote a post about the Reserve Bank’s announcement that it had increased Westpac New Zealand Limited’s minimum capital requirements – by quite significant amounts – “after it failed to comply with regulatory obligations relating to its status as an internal models bank”.

Two things in particular annoyed me last week:

- the complete lack of any serious explanation, from either the Reserve Bank or Westpac, as to what had gone on and why, how and by whom the errors were uncovered, what remedial steps had been taken (in both institutions), how we could be sure similar problems didn’t exist in other banks, and

- the absence from both statements (Reserve Bank and Westpac) of any reference to Westpac’s directors, even though under our system of bank regulation and supervision, the directors have primary responsibility for attesting to the accuracy of disclosure statements, and face potential civil and criminal penalties for (strict liability) offences for publishing false information.

One can understand why Westpac would not want to say anything more, even if (for example) they thought the Reserve Bank had overreacted: don’t upset the regulator is one of the watchwords of the banks, because even if your concern might be justified on one point, the Reserve Bank has many other ways to get back at you on other issues (where, eg, approvals are needed) if you make life difficult.

The Reserve Bank’s stance is more disconcerting. It is, after all, a government regulatory agency, responsible to the public for the exercise of its statutory powers, and for the management of its own operations. And yet, as so often with monetary policy, they seem to think it is up to them to decide how much they will graciously tell us, rather than to be accountable and answer the questions that people have. I gather they are refusing to explain themselves further at all. If, as it says it is, the government is serious about increasing the transparency of the Reserve Bank, this is just another example of why reform – and a new culture – is needed.

When I wrote last week, there were several things I didn’t notice.

First, I noticed the lack of any sign of contrition in the Westpac statement, but didn’t go on to draw the obvious conclusion that lack of any sign of contrition – even feigned for the public – might suggest that they felt they were being rather unjustly dealt with in this matter. Had they been caught out doing seriously bad stuff, you’d have expected them to, if anything, overdo the public contrition (mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa and all that).

Second, the Reserve Bank’s statement was clearly designed to have us believe that there had been systematic problems for nine years now, ever since Westpac was first accredited to use internal models. Why do I say that? This is what they said.

The report found that Westpac:

- currently operates 17 (out of 35) unapproved capital models;

- has used 21 (out of 32) additional unapproved capital models since it was accredited as an internal models bank in 2008;

But someone pointed out to me Westpac’s initial disclosure of the problems in its September 2016 disclosure statement. In that statement (page 9) Westpac disclosed a couple of trivial errors dating back to 2008 (in sum, lifting risk-weighted assets by $44 million on a balance sheet of $86 billion). And what about the model approvals errors? Well, this is what the directors’ disclosure says:

“The Bank has identified that it has been operating versions of the following capital models without obtaining the Reserve Bank’s prior approval as required under the revised version of the Reserve Bank’s Capital Adequacy Framework (Internal Models Based Approach)(BS2B) that came into effect on 1 July 2014”

If it is correct that prior to July 2014 internal models banks did not require Reserve Bank approvals for specific models (and I have now have vague recollections of internal discussions on exactly this point in 2013/14, and an earlier version of BS2B does not have the requirement) that would put a rather different light on Westpac’s errors than was implied in the Reserve Bank statement. Transition problems associated with a pretty new requirement look rather different than a failure that had run for nine years since the inception of the Basle II regime.

The original conception of allowing banks to use internal models to calculate risk-weighted assets (for capital adequacy purposes) had not been to have the Reserve Bank micromanaging the process, but rather reaching an overall judgement about the ability of banks to responsibly use such models, while imposing supervisory overlays where the Reserve Bank thought the models were producing insufficiently cautious results (as we did from day one in respect of housing mortgage exposures). Over the years, the Reserve Bank grew less confident in the internal models approach, culminating (apparently) in the 2014 requirement that all models have prior Reserve Bank approval.

As the situation stands now

Registered banks may only use approved internal models for the calculation of their regulatory capital adequacy requirement. Banks must advise the Reserve Bank of all proposed changes to their estimates and models before implementing them.

There are specific requirements laid down about the information banks have to submit to the Reserve Bank when seeking such approvals. I’ve been told that the Reserve Bank can then take up to 18 months to work through the process of approving any change (there are, after all, 32 models for Westpac alone, and four internal-models banks).

The Reserve Bank also requires that

A bank that has been accredited to use the IRB approach must maintain a compendium of approved models with the Reserve Bank. This compendium has to be agreed to by the Reserve Bank and only models listed in that compendium may be used for regulatory capital purposes. The compendium is to be reviewed and relevant sections are to be updated at least once a year. The compendium must be updated as soon as practicable after a model change has been approved by the Reserve Bank. The compendium lists basic model-related information such as version number, approval date, risk drivers, key parameters, as well as information from the most recent annual validation report on RWA, EAD, validation date and model outlook, and any other model-related information required by the Reserve Bank.

All of which sounds sensible enough, but it raises some obvious questions. If this was a new requirement in 2014 (but in fact whenever the requirement was introduced), surely the Reserve Bank would have insisted on a compendium from each bank of the models that bank was using at the time, and then would have put in place a process to (a) monitor any changes it was approving, and (b) ensure, whether by directors’ attestation or whatever, that any changes to the models banks were using actually had prior Reserve Bank approval. But did any of this happen?

Since we don’t have anything in the way of a good explanation from either Westpac or the Reserve Bank we can only guess at what must have happened. I’m pretty sure Westpac didn’t consciously set out to deceive the Reserve Bank – the banks are gun-shy, terrified of breaching conditions of registration – and the Reserve Bank’s own statement seems to accept that story.

Perhaps there is a clue in this line from the Reserve Bank statement as to what the independent investigation found. Westpac New Zealand

failed to put in place the systems and controls an internal models bank is required to have under its conditions of registration.

Most or all of the risk modelling work is likely to have been being done in Sydney (by the parent bank) and not by Westpac New Zealand at all. Quite possibly, people on this side of the Tasman only ever see the bottom line numbers, and pay no attention to the modelling or (small?) changes in it. Perhaps Sydney went on refining risk models, including updating the models for changes in data composition (as the composition of individual loan portfolios changes), and just didn’t know that they were now (unlike the first few years as an IRB bank) required to notify and get Reserve Bank approval for each and every change? If so, it is still a system failure – and potentially of concern for the way it highlights how things could go more seriously wrong – and shouldn’t have been allowed to happen, but it doesn’t seem like the most serious failing in the world. Did the Reserve Bank see Westpac’s model compendium in 2015, and if so did they confirm with the Westpac risk people in Sydney (presumably who they are primarily dealing with) that the models in the compendium, and only those models, were being used? If so, why it did it take another year to uncover the problems. And if not, why not?

Without a proper explanation, we don’t know if this is the story. But depositors and creditors should be owed an explanation by Westpac, and the public are owed one by our regulator, the Reserve Bank.

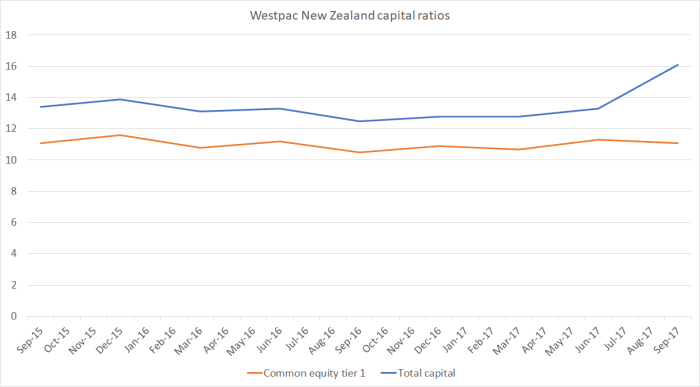

The third thing I didn’t pay much attention to last week was the statement that Westpac now had a total capital ratio (share of risk-weighted assets) of 16.1 per cent. It seemed surprisingly high, but it was higher than the (temporarily increased) regulatory minima, and than the level Westpac had undertaken to maintain, so I passed over it quickly, and I shouldn’t have.

Here are Westpac New Zealand’s capital ratios (common equity tier one, and total capital) for the last couple of years. The data are taken from disclosure statements and, for September 2017, from Westpac’s press release last week.

I couldn’t find any reference anywhere to Westpac New Zealand Limited having issued any capital instruments on market in the September 2017 quarter. But the Westpac New Zealand branch did issue $US1.25 billion of perpetual subordinated contingent convertible notes in September. Those instruments would qualify as Tier One capital (though, of course, not as common equity). Since we don’t yet have the September disclosure statement, we can’t be sure what went on, but it looks as though the proceeds of that issue might have been used to subscribe to (eg) a private placement of similar securities by Westpac New Zealand to its parent. Whatever the story, it seems unlikely that the sudden increase in Westpac New Zealand’s capital ratio had nothing to do with the fight they were then no doubt in with the Reserve Bank about the appropriate response to the model-approvals issue.

Again, we deserve a better explanation from the Reserve Bank (and Westpac) as to what actually went on. For example, did the Reserve Bank insist that Westpac take on more capital, even beyond the temporarily increased regulatory minima, and then let Westpac raise the additional capital before letting the public (and depositors/creditors) in on what was going on? Perhaps not, but the alternative – in which Westpac New Zealand just happened to decide to raise more capital just before the regulatory sanction was announced – seems a bit implausible. The news coverage would have been at least subtly different if last week’s announcement of the model approvals errors had been accompanied by the statement that Westpac New Zealand would need now to take steps to increase its level of capital (as distinct from just glossing over a fait accompli).

Which also brings us back to the unanswered questions? We don’t know how much difference the use of unapproved models actually made to Westpac’s risk-weighted assets – in fact, we don’t even know if the Reserve Bank knows. And we don’t know if the Reserve Bank insisted on this new capital – although it seems likely given that they noted that

In addition, the Reserve Bank has accepted an undertaking by Westpac to maintain its total capital ratio above 15.1 percent until all existing issues have been resolved.

when 15.1 per cent is well above even the temporarily higher regulatory minima for Westpac.

But if so, is the penalty proportionate to the offence? It is impossible to tell, on the information the Reserve Bank has so far made available, and that isn’t a good state of affairs – no basis for holding this (weakly-accountable) regulator to account.

And, to return to one of the questions I posed last week, why wouldn’t prosecution of the directors have been a more appropriate penalty, and one better-aligned with the design of the regulatory framework? I’m not suggesting anyone should have gone to prison, but if what actually went on here was a governance design failure, surely it is an obvious case for trying out the penalty regime designed to ensure that directors do their job (of, among other things, ensuring that management do their job)? A fine on each director – for what are, after all, strict liability offences – looks as though it could have been a more appropriate penalty. But if such prosecutions had been contested, that might have forced the Reserve Bank to disclose more, including about their own system failures, than perhaps they would have been comfortable with? Bureaucrats protect themselves, and their bureau.

As I said last week, I hope journalists use the opportunity of the Financial Stability Report press conference next week to pose some of these questions to the “acting Governor” and Geoff Bascand, the new Head of Financial Stability. They can’t force the Reserve Bank to answer questions, but if the Bank continues to stonewall, in the face of repeated questions from multiple journalists, in a news conference that is live-streamed, it won’t be a good look for the Reserve Bank (or for Geoff Bascand personally, if he is still in the race to become the next Governor).