There are some interesting things in the Reserve Bank’s Financial Stability Report, some questionable ones (including, at the mostly-trival end of the scale, Grant Spencer’s assertion that he is “Governor” when by law he is, at best, “acting Governor”) and some things that are missing altogether.

The Reserve Bank observes that banks have tightened their own (residential mortgage) lending standards

Banks have tightened lending standards, reducing the borrowing capacity of households. Typically, banks are using higher interest rates when assessing the ability of borrowers to service a new mortgage and their existing debt, restricting the use of foreign income in serviceability assessments, placing stricter requirements on interest-only lending, and ensuring that living expenses assumed in a loan assessment are reasonable given the borrower’s income.

If so, you have to wonder why the Reserve Bank is still intervening in such a heavy-handed way in the decisions banks would otherwise make about their mortgage lending.

But they go on to back their claim with an interesting, but on the face of it somewhat dubious, chart

The overall impact of the tightening in banks’ lending standards is illustrated by the Reserve Bank’s recent hypothetical borrower exercise, which asked banks to calculate the maximum amount that they would lend to a range of hypothetical borrowers. This repeated an exercise that was conducted in 2014. The 2017 results suggest that maximum borrowing amounts have declined by around 5-10 percent since 2014 (figure 2.3).

But it is hardly surprising that, with the same nominal income, banks would lend a little less now than they would have been willing to do so in 2014. After all, there has been three years’ of inflation since then. Even if the borrowers had declared the same monthly living expenses to their bank, banks use their own estimates/provisions for living expenses in deciding how much to lend. Supervisors, indeed, encourage them to do so, and to be sure to leave adequate buffers. An income of $120000 would comfortably support more debt in 2014 than the same income does in 2017 (the reduction in the maximum amount lent to owner-occupiers was 3.5 per cent in the chart). It would probably be better to do all these comparisons using inflation-adjusted inputs.

In this FSR, the Reserve Bank reports the results of their latest set of bank stress tests. This year’s macro stress test didn’t seem particularly demanding in some ways.

Previous scenarios have featured falls in house prices of more like 50 per cent (in Auckland) and 40 per cent nationwide, which seemed like suitably tough tests. Previous test also featured an increase in the unemployment rate to 13 per cent (which was so implausible that I pointed out then that no floating exchange rate advanced country had ever experienced such a large sustained increase in its unemployment rate).

But there are several unrealistic things about this scenario

- it is highly improbable that even a severe recession in another country would lower New Zealand house prices by 35 per cent. A massive over-supply of houses here might do so, or even the end of a massive credit-driven speculative boom, but neither an Australian nor Chinese recession is going to have that sort of effect. In the 2008/09 recession – as severe a global event as we’d seen for many decades – we saw about a 10 per cent fall in nominal house prices in New Zealand.

- it is also highly unlikely that house and farm prices would fall by much the same amount in this sort of scenario. Why? Because in this scenario it is all but certain that the exchange rate would fall a long way (helped by the fact that the Reserve Bank has more scope to cut interest rates than their peers in other countries), in which case the dairy payout (and any fall in farm prices) will also be buffered relative to the fall in prices of domestic-focused assets.

- But perhaps most implausible of all was the requirement that “banks’ lending grows on average by 6 per cent over the course of the scenario”. Governments of the day might, at the time, be keen for banks to keep taking on more credit exposures, but those private businesses – amid a pretty severe shakeout – are unlikely to be willing to do so. And there wouldn’t be many potential borrowers. If the asset base was stable – or even shrank a bit, as it would tend to do naturally with sharply lower asset prices – a fixed stock of capital goes quite a bit further.

As it is, once again the stress tests suggests that on the lending practices banks have operated under over recent years – and they can change – our big banks are impressively resilient. Here is the key chart.

The chart is presented to make the deterioration in banks’ capital positions look large (by being presented as a margin over the minimum regulatory capital, rather than an absolute capital ratio – creditors lose money when banks run out of capital, not when they get to the regulatory minimum). But even then, look at the results. The blue line is the result if the banks do nothing in response. Which bank would do that in the middle of a period of multi-year stress? But even then, at worst, the banks in aggregate end up with a buffer of capital of 2 percentage points above their required minimum. With mitigants – the red line – they never even dip into the capital conservation buffer (the margin over the minimum; if banks dip into that zone there are limits of their ability ot pay dividends).

It is good that the Reserve Bank does these stress tests. It would be better if they provided more information on the results (eg in this scenario they tell us that half the credit losses come from farm lending and residential mortgage lending, but don’t provide the breakdown – from previous tests’ results, I suspect the residential contribution is relatively small – and don’t give any hint where the other half of the losses is coming from (given that housing and farm lending get most of the coverage in FSRs).

It must surely be hard to justify onerous and distortionary controls on access to credit for one large sector of borrowers when year after year the results come back showing that the banks look pretty robust to pretty severe shocks. And when the Bank also tells us that the prudential regime isn’t designed to avoid all failures. In combination, could one mount an argument that banks aren’t being allowed to take enough risk?

Operating in a market economy, banks in New Zealand – and those in Australia and Canada – appear to have done a remarkably good job of managing their own risks and credit allocation choices. It is, after all, more than a 100 years since a major privately-owned bank has failed in any of those three countries. Things can go wrong – and often have in heavily distorted financial systems (eg that of the United States) – and bank regulators are paid to be vigilant, but it might be nice – just occasionally – to hear senior Reserve Bankers pay credit to the competent (never perfect) management of the risks our banks take with their shareholders’ money.

I mentioned things that were missing entirely from the FSR.

The Reserve Bank Act requires FSRs to be published

A financial stability report must—

(a) report on the soundness and efficiency of the financial system and other matters associated with the Bank’s statutory prudential purposes; and(b) contain the information necessary to allow an assessment to be made of the activities undertaken by the Bank to achieve its statutory prudential purposes under this Act and any other enactment.

That second item is no less important than the first. And when the Reserve Bank has, during the period under review, imposed significant regulatory sanctions on a major bank you might have supposed that in the next FSR there would be a substantial treatment of the issue (there is, after all, more space than in a press release). It is, after all, an accountability document, designed to allow the public (and MPs) to evaluate the Reserve Bank’s handling of its responsibilities.

But in the case of the recent Westpac breach (operating unapproved capital models), which resulted in big temporary increases in Westpac’s minimum capital ratios and – it appears – a requirement that Westpac issue more capital over and above those minima you would be quite wrong. I read the entire document yesterday and didn’t spot a single reference. A proper search of the text revealed a single footnote, which simply noted that Westpac’s minimum capital ratios had been increased, with a link to last week’s Reserve Bank press release.

This really should be regarded – by the Board, by MPs, by citizens and other stakeholders – as unacceptable: an organisation, that despite its constant claims, seems to regard itself as above any sort of serious public accountability, despite the clear requirements imposed by Parliament. You will recall that last week I noted that there was a range of unanswered questions about this whole episode (here and here). The FSR answered none of them. For example:

- who discovered the error, and how?

- how did it happen (both at the Westpac end, and at the Reserve Bank end)?,

- what confidence can we have that there are not similar problems at other banks?,

- what changes has the Reserve Bank made to its own procedures to reduce the risk of a repeat?

- why was there no reference in the Reserve Bank statement to the failures of Westpac directors (even though director attestation is supposed to be central to the regulatory regime)?

- did the Reserve Bank compel Westpac to raise new capital?

- how much difference did the use of unauthorised models make to Westpac’s capital ratios?

Jenny Ruth of NBR (who covered the story in a column last week, noting that the Bank’s failure then to provide more information was “appalling”) asked some questions about the issue at press conference yesterday. The answers weren’t particularly clear or helpful.

She asked why no directors were prosecuted (these were, after all, strict liability offences, and director attestations are a key part of the regime). Grant Spencer basically refused to answer, just claiming that the steps they had taken were a “strong regulatory response”.

She asked about the other internal-ratings banks and whether there were such problems with them. The first answer seemed to suggest that the Bank was confident, having checked, that there were not. But as Spencer and Bascand went on, even that seemed to become less clear. By the end it seemed to be a case of “we aren’t aware of any other problems and we are encouraged that some are having a look to check”. It didn’t exactly seem like an aggressive pro-active response by the Reserve Bank, to a potential problem it has known about for more than a year (since the Westpac issues first came to light). It turns out that ASB has had other problems around its capital calculations (apparently without penalty).

We learned one thing. Asked who first uncovered the issue – Ruth suggested she had heard that Westpac had uncovered the problem itself – the Bank representatives responded that they had had their own suspicisions and had raised the matter with Westpac, who had then confirmed that there was a problem. That was good to know, but it was only one small part of the questions that should be answered.

It is, perhaps, getting a bit repetitive to say so, but if the new government is at all serious about more open government – and serious media outlets have raised questions about that in recent days – then the Reserve Bank would be a good place to start. The culture needs changing, and culture change is only likely to come from the (words and actions at the) top. How the government can expect to find a Governor who would lead the Bank into a new era of openness and transparency when they are relying on the Board – always emollient, always keen to have the Governor’s back, never revealing anything, never even documenting their meetings in accordance with the law, – is a bit beyond me. Sadly,a more probable conclusion is that the government doesn’t really care much, and that the repeated promises by Labour, the Greens, and New Zealand First around the Reserve Bank were more about being seen to make legislative changes, rather than actually bringing about substantive change in the way this extraordinarily powerful, not very accountable, agency operates. If so – and I hope it isn’t – that would be a shame.

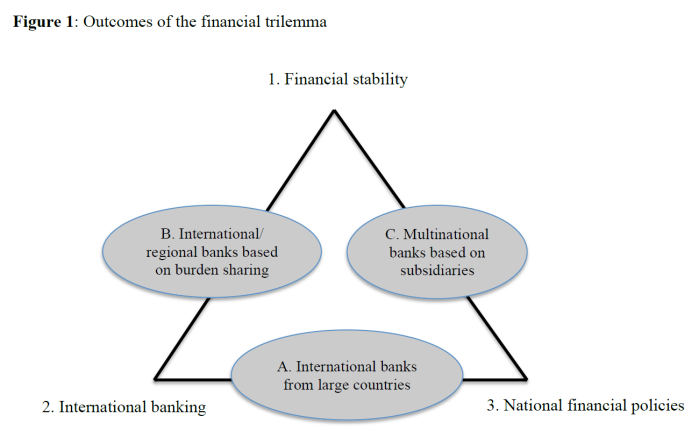

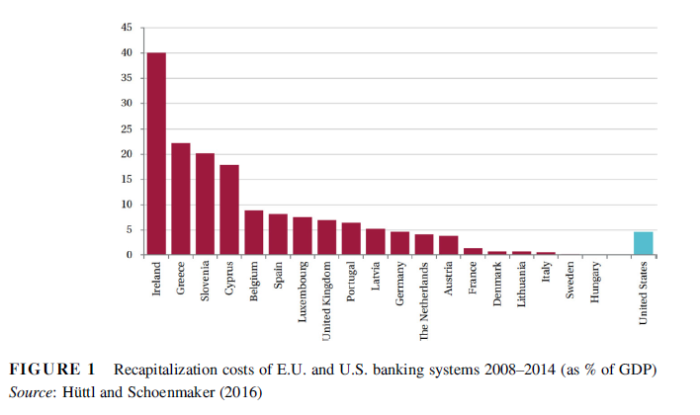

As he notes, the first four countries on the left of the chart couldn’t cope themselves and needed either IMF or EU support, and Spain also needed external assistance. But all these countries were in the euro-area, and thus not only lost the capacity to adjust domestic interest rates for themselves, but also couldn’t do anything to adjust the nominal exchange rate. By contrast, the UK’s bailout costs – not that much lower than Spain’s – never ever raised any serious questions about the UK’s fiscal capacity. And that was with a far higher starting level of public debt (as a share of GDP) than, say, Ireland had.

As he notes, the first four countries on the left of the chart couldn’t cope themselves and needed either IMF or EU support, and Spain also needed external assistance. But all these countries were in the euro-area, and thus not only lost the capacity to adjust domestic interest rates for themselves, but also couldn’t do anything to adjust the nominal exchange rate. By contrast, the UK’s bailout costs – not that much lower than Spain’s – never ever raised any serious questions about the UK’s fiscal capacity. And that was with a far higher starting level of public debt (as a share of GDP) than, say, Ireland had.