It was Paul Krugman, winner of the economics pseudo-Nobel Prize who famously captured one of the fairly basic insights of economics. When it comes to material living standards in the medium to longer-term, if productivity isn’t everything, it is almost everything. The terms of trade bob around, but probably won’t do much (harm or good) over the longer term, as they haven’t in New Zealand over 100 years. But productivity growth – managing to produce more per unit of inputs – is the basis for improved material living standards. The best timely and accessible measure of productivity, widely used in international comparisons, is real GDP per hour worked.

Productivity growth in New Zealand has been pretty lousy in New Zealand for many decades, really since around the end of World War Two. We’ve had the odd decent run, but over the decades we’ve had one of the lowest rates of productivity growth of any advanced country. We’ve slipped down the OECD league tables, and now part of the way we maintain reasonable living standards is by putting many more hours, over a lifetime, than the typical person in an advanced country.

Across the advanced world, productivity growth seems to have slowed from around 2005 (before the financial crisis). We didn’t need to share in that slowdown, because productivity levels in New Zealand were so far below those of the OECD leaders. Countries like the Netherlands, France, and Germany – which historically we were richer and more productive than – now have labour productivity levels around 60 per cent higher than those of New Zealand. We should have been able to close some of the gap in the last decade or so, utilising existing technologies, even if advances at the technological and managerial frontiers were slowing. Various other poorer OECD countries – notably the former Soviet bloc countries that are now part of the OECD – have done so. We haven’t.

Several weeks ago the Prime Minister and the Minister of Finance were repeatedly claiming that New Zealand’s productivity performance in recent years had really been pretty good. In fact, they suggested that under their watch we’d managed faster productivity growth than in other advanced economies and that the gaps were beginning to close.

I went to some lengths to unpick those claims. New Zealand doesn’t have an official measure of real GDP per hour worked (unlike Australia, where the ABS routinely reports numbers as part of their national accounts release). Instead, we have two measures of real GDP (expenditure and production), and two measures of hours (HLFS and QES). Instead of just picking on one combination, I calculated all the possible methods, and looked at them individually and on average (nine in total).

For broad-ranging international comparisons, it often makes sense to use annual data, because not all countries have easily accessible quarterly data. Unfortunately, the annual data are often only available with a lag, and the OECD doesn’t yet have annual data on real GDP per hour worked for all countries for calendar 2016. But in the years from 2008 to 2015, on not one of the possible New Zealand productivity measures did New Zealand quite manage productivity growth as fast as that of the median OECD country.

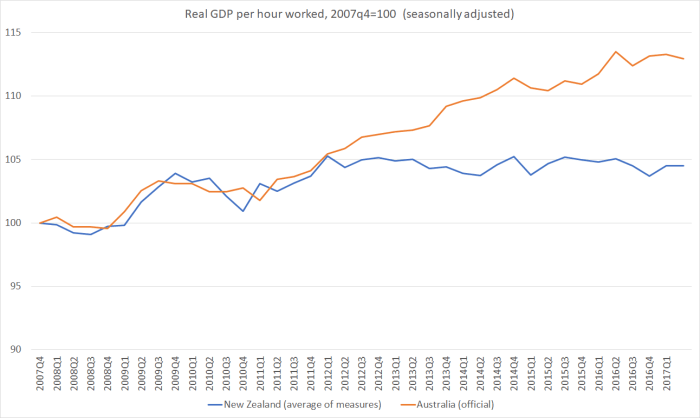

This morning Statistics New Zealand released the latest quarterly national accounts, which enabled me to update the various quarterly productivity series. In this chart I’ve shown the average of the various possible measures, and compared the performance of New Zealand relative to that of Australia (using the official Australian data). I’ve started the chart in the last quarter of 2007, just before the 2008/09 recession began.

Over the first few years, through the recession period and in the year or two beyond, productivity growth in New Zealand and Australia was modest, but we more or less kept pace. But what is striking is how increasingly large and persistent the deviation has been since around the start of 2012. Over the five years, we’ve had no productivity growth at all, and Australia has managed quite reasonable growth. And over the last five years, using the average measure for New Zealand doesn’t mask anything: from the second quarter of 2012 to the second quarter of 2017, the strongest of the nine series recorded productivity growth of 0.8 per cent (that is, in total over five years) and on the weakest, the level of productivity fell by 0.6 per cent (in total over five years). Best guess: zero.

Recall that at the start of the period the average of level of productivity in Australia was already well above that in New Zealand. That gap has widened still further. In the early days of this government readers will recall that there was a goal to close those gaps to Australia by 2025, only eight years away now.

It has been a dismal performance. Productivity isn’t mostly about how hard people work, but is much more about the ability of firms to find opportunities here that generate high incomes, and in particular high wages. That is very difficult when the real exchange rate is as persistently high as it has been here. Particularly over the last few years, very rapid population growth has underpinned the strength of the real exchange rate, driving up the prices of non-tradables relative to those of tradables.

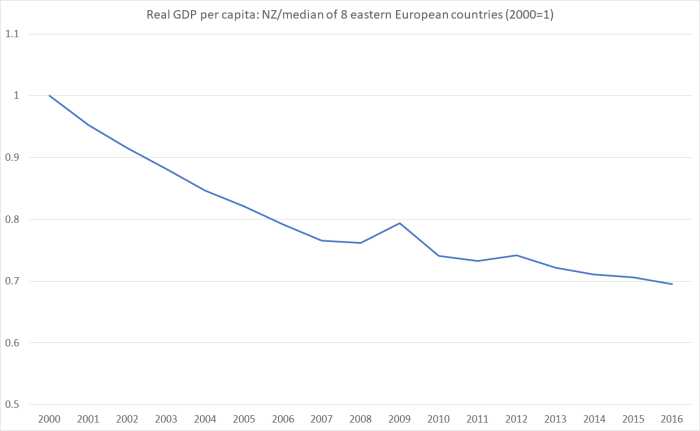

And what of the comparison I mentioned earlier with the former Soviet-bloc central and eastern European countries (Slovenia and Slovakia, Poland and Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia)? Thirty years ago, all of them were in a much worse state than New Zealand, but like New Zealand they had an aspiration to reverse decades of economic underperformance and catch-up with the richer countries in the OECD – in their case, particularly those in western Europe. But here is how we have done relative to them over the period since 2000, when there is consistent data available for all the countries (and by then all the other countries had got well through the nasty shakeouts immediately after the fall of communism).

It is a steady and substantial decline in our productivity levels relative to those of these central and east European countries. The data are only annual, of course, but as you can see in earlier chart, we’ve had no productivity growth at all recently so not incorporating the last couple of quarters won’t help the picture. Some of these countries – communist-era basket cases 30 years ago – now have levels of productivity very similar to New Zealand’s. Most are on a path that may well take them past us in the next decade or so. Most, as it happens, have little or no population growth. They make the most of their opportunities – which are considerable, being close to western Europe – with their own people.

To sum up, New Zealand has lagged a bit behind the median advanced country since 2007/08, and has had no productivity growth at all for the last five years. We continue to drift further behind our closest neighbour, Australia, and now face the likelihood that before too long we’ll be overtaken by countries that, throughout modern history, were never previously as productive as New Zealand was, and which 30 years ago we’d have looked on as pretty hopeless cases. We could do much better, but there is absolutely nothing to suggest that we will manage to do so pursuing current economic policies. Sadly, there isn’t much sign that any of the parties competing for your vote on Saturday are offering anything materially different, that might finally begin to reverse almost 70 years of continuing relative decline. The apparent refusal of our leaders to face the reality, and make steps to change, won’t alter the fact of our continuing relative economic decline.

Michael, I share your frustration, but, as tempting as it may be, it just doesn’t pay to get too excited about this triennial pre-election circus that parades as ‘democracy’ in this country. Rather than getting our hopes up, it would pay to listen to “the markets” instead. As Cameron Bagrie said on RNZ this morning: “New Zealand is very centralist with respect to where economic and policy direction tends to go, so it [the outcome of the election] doesn’t really matter … the broad basic economic framework is going to remain in check .. by and large the economic direction is not going to be too dissimilar post election.”

And Derek Rankin adds: “… overall the international investors, you gotta remember, don’t see there is a lot of difference between National and Labour … the two parties are not that far apart on an international scale.” As in most other ‘Western democracies’, the political and economic system is fairly well buffered against change – until next time the proverbial hits the fan again.

LikeLike

“Two sides of the same coin” is the way I’ve described the two main parties in various posts here over time.

I have very little expectation, sadly. But in a sense that’s fine. The same problems, the same failures, the same political-corruption (see the China posts) will be here on Monday, and I’ll keep writing about them. The worry is, of course, the next generation. In a few years my kids will be leaving school. Sadly, I’m not sure I could encourage them to stay, at least on economic/financial grounds.

LikeLike

…re you final point:

http://www.epicwestport.co.nz/

https://www.trademe.co.nz/property/residential-property-for-sale/west-coast

“No such thing as bad weather – just inappropriate clothing….”

LikeLike

Not bad if, say, one wanted to be a primary school teacher: national salary, and subnational house prices. Fortunately one of them does….

Then again, as past commenters have pointed out occasionally, you can buy brand new houses on the outskirts of growing US cities for those sorts of prices.

LikeLike

The economic/financial grounds in NZ certainly is great at the moment for my daughter. She finishes off her undergraduate degree in Europe over the next 6 months and will return to job that she secured prior to leaving for Europe. I have suggested that she looks at a UN position while she is in Europe. But she is quite adamant about returning to NZ with a $50k position already secured with a large multinational company.

As she studied at University of Auckland, I had secured an apartment for her which she funded through her interest free student loan and she rented out a room to her friend to help pay for the apartment. Afterall why pay rent when you can own.

The property has been setup under a corporate trustee structure with the Family Trust as the owner. With Labour and greens intending to tax 2nd properties which pretty much is a inheritance tax. I am unsure if her property under the family trust will be considered a 2nd property.or my daughters 1st property. Looks like a lot of restructuring work for lawyers and accountants.

If you plan properly for your kids then I see no reason why your kids would not have a Bright and exciting future in NZ. It is failure to plan and a failure to do the hard work that leads to failure economically and financially in NZ. NZ is a land of milk and honey as far as I am concerned.

LikeLike

GetGreatstuff: your post reminded me of Billie Holiday’s lyrics that start:

Them that’s got shall get

Them that’s not shall lose

So the Bible said and it still is news

and in the 3rd verse

Rich relations give

Crust of bread and such

You can help yourself

But don’t take too much

However I did much the same with my daughters studying in Auckland a decade ago – ended up buying a city apartment that neither daughter ever occupied but which has been a great investment ever since.

LikeLike

Two imports talking to one-another

LikeLike

I fear that the quality of politics, democracy and governance will take a turn for the worse. There is a very good chance that NZ politicians will realise that post-truth politics is a successful strategy -that it worked in 2017, so they will double down on it in the future. Like bad money driving out good. Post-truth politicians will drive out those of integrity. This will surely reduce the likelihood that NZ’s tackles its pressing social and economic problems

View at Medium.com

I too worry about my boy’s future.

LikeLike

Apropos this comment from an earlier article

https://croakingcassandra.com/2017/09/21/immigration-the-election-and-shelf-stackers/#comment-18648

This article is about Productivity of New Zealand but relies on GDP and Hours Worked

Summarising a number of articles we are informed that the “growth” in outright GDP is largely attributable to immigration levels at a greater than any other country in the OECD – to some purpose – IMO it is to breed our first-nations people out of existence

NZ should be able to measure

(a) Total GDP

(b) GDP attributable to immigrants

(c) GDP attributable to locals

(d) what sectors migrant are flowing to tradeables v non-tradeables

We need some evidence of how and where the benefits are coming from

Without that information obtained in an official form nothing will change

On the face of it Statistics NZ has been subjected to budgeting-out while the population gets bigger, migration keeps on unhindered, government keeps striving for surpluses at the expense of – you name it

LikeLike

Worth reading Paul Krugman’s “Notes on Immigration” from 2006 https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2006/03/27/notes-on-immigration/?_ where he explains the economic effects of immigration at a level I can just about grasp. Strangely he is rarely mentioned when we are told economists have proved immigration is good for the economy.

LikeLike

“Beijing: The plight of a Chinese student whose parents sold their home to pay for an Australian university education but only found a job handing out product samples has sparked debate in China questioning the value of overseas education.

The worsening job prospects for graduates returning to China could send a chill through Australia’s third largest export market – international education – which is worth $21.8 billion annually”

http://www.smh.com.au/world/chinese-students-question-australian-education-sending-chills-through-industry-20170919-gykfgi.html

Make hay while the sun shines which means this export market may be dwindling fast in the future without the nonsense from Labour. Jacinda Ardern with her loose tongue and her shoot from the hip Captain’s call about taking out international students by 30,000 would be hugely costly for a $4 billion export industry. Totally unnecessary and could be very discouraging for the millions of dollars spent by the Universities and colleges in marketing NZ institutions overseas.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the info. Jacinda and the Labour party have been very quiet about their immigration plans. At a public meeting in Highbury when Andrew Little was still the boss Jacinda and Andrew carefully made no mention of immigration despite Highbury being one of the most contentedly multi-ethnic communities in Auckland. My understanding of their policy was a desire to remove the rorts and worker exploitation involved with current student visa regulations; if so they will not stop any student who is coming for education but will be dissuading those who are looking for permanent residency. Whether that will cause all 30,000 to stop coming to NZ is debatable. It certainly makes sense for a party called ‘Labour’ to be concerned about exploitation and the driving down of wages for low-skilled Kiwis.

LikeLike

[…] The actual level of GDP is now a bit higher than had previously been reported, but what caught my eye was the reported claim from the former Minister of Finance, Steven Joyce, that the new data suggested that there was no productivity growth problem after all. You’ll recall that for some time I – and others – have been highlighting data suggesting that there had been basically no productivity growth at all in New Zealand for the last five years. […]

LikeLike