Alex Tarrant, at interest.co.nz, has done a couple of interesting interviews, one each with the current Minister of Finance, Steven Joyce, and with the man who would replace him, Labour’s Grant Robertson. There are various things in each interview that I might comment on in the next few days – including in particular Robertson’s comments on his plans re the Reserve Bank.

In the interview with Joyce, this blog even got a mention, as the Minister was forced to concede that five years of no productivity growth (at least as measured at present) might perhaps be something that should be taken seriously.

“Productivity has been a struggle everywhere. If you look across the eight years – and let’s be clear, these people that talk about productivity measures over a year, they’re really…”

I cut in: former Reserve Bank economist, and Croaking Cassandra blogger Michael Reddell’s talking about the last five years, when productivity growth has been negative by most measures.

“Five years is getting more like it,” he accepts. “The thing about measuring productivity is it’s generally measured more effectively a couple of years after the fact, which is very frustrating for those us who are focussed on it,” he said.

So now, apparently, we are reduced to just hoping that the last few years’ data end up revised away? Maybe……

But today I wanted to focus on Joyce’s comments around the New Zealand export performance and the government’s export target, partly because on this occasion he has articulated his perspective more fully than I’ve seen previously. Here is the heart of that section of the interview

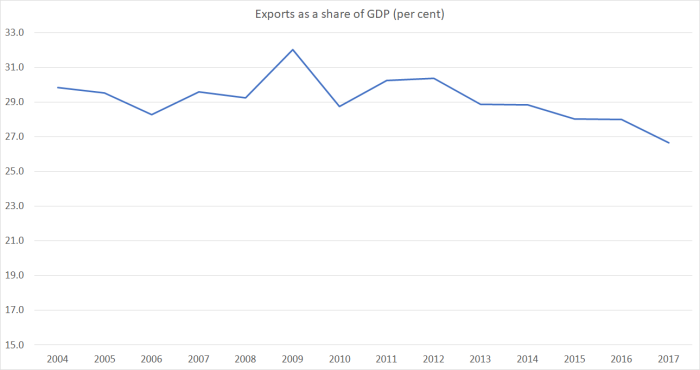

I ended by putting a couple of numbers to Joyce – one was on the goal to increase exports as a proportion of GDP from 30% to 40% by 2025. It hasn’t shifted from 29% since 2008. Is he disappointed?

“I’d like to see more growth in that.” He couldn’t really have said much else. “But you have to go and look at what’s been happening under the hood. And under the hood, world trade intensity has dropped.

“So, if you look at New Zealand relative to say, your Singapores, your Denmarks or so on, which are the big traders, they’ve gone back a bit, because we’ve had an extended period of a decline in world trade,” he says.

“We’ve held our own. Again, it’s nothing to write home about necessarily, except that we haven’t slipped back the way other countries have.”

Another thing New Zealand had been dealing with was our biggest export had been “down a bit of a hole over the last two or three years,” Joyce said (about dairy).

Actually, Tarrant’s introduction is a bit generous. Exports as a share of GDP in New Zealand were 29.2 per cent in the year to March 2008, rose quite a bit when the exchange rate plummeted in the following year, but were down to 26.7 per cent in the year to March 2017. The last time the export share was lower than that was 1990.

What of the Minister’s claim about what’s gone on in the rest of the world? It isn’t entirely clear how relevant it is to New Zealand anyway, given that the government has set, and regularly updated, the New Zealand target, including in the Business Growth Agenda refreshes as recently as this year. But set that to one side for the moment. What do the data show, and how do we compare?

For the whole world, the best source of data is the World Bank. Often it is only available with a bit of a lag.

For the world as a whole, exports as a share of GDP have indeed dropped slightly since 2007 or 2008. But that is very largely a China story – after a couple of decades of very strong export-led growth, the story of China in the years since the 2008/09 recession has been a domestic credit and infrastructure phase. The foreign trade share of GDP has fallen back a long way – and is probably still above what would expect in the long-term for a country the size of China. For high income countries (a World Bank category) exports haven’t grown markedly as a share of GDP, but they have grown. Of the Minister’s other examples, Singapore’s export share is very high and quite volatile, and has fallen back somewhat – as I illustrated in a post a few months ago, they’ve had a huge increase in their real exchange rate – but Denmark’s hasn’t.

The usual group we compare New Zealand against is the other advanced economies in the OECD. Here is how New Zealand has done relative to the median OECD country.

The shifts aren’t dramatic but (a) we’ve done less well than them, and (b) we were the country whose government set a target for a dramatic change.

If we use calendar year 2007 as a reference point (the last full year before the recession), there are a few countries whose (nominal) export share of GDP has dropped by materially more than New Zealand’s. They are Chile, Israel, and Norway. Of them, Chile and Norway have experienced very substantial falls in their terms of trade – sustained falls in copper and oil prices. By contrast, New Zealand(despite the ups and downs in dairy prices) and Israel have had the largest increases in the terms of trade of any OECD country over that (almost) decade. All else equal, a rising terms of trade should have tended to lift a country’s export share of GDP relative to those in other countries (matched, in time, by a higher import share of GDP, as the proceeds of the better prices are spent).

All of these numbers to date have been measures of the nominal value of exports relative to nominal GDP. The government has expressed its export target in terms of volumes. As I’ve noted before, ratios of real variables don’t make a lot of sense, and Statistics New Zealand advises against using them. But one way of looking at volumes that does make some sense is to compare the volume growth of exports to the volume growth of GDP over a reasonable period. In this case, I’ll look at the most recent year (to March 2017) relative to that last pre-recession year, calendar 2007.

In this chart I have calculated the total percentage growth in the volume of exports since 2007 and substracted from that the total percentage growth in real GDP over that same period. (It might be more proper to do this multiplicatively, but I’ve checked and it doesn’t change the rankings.)

There are OECD countries that have had a weaker relative export volume performance than New Zealand over this period, but not many. And the median country’s experience is very different than ours has been. And that is even with all those subsidised additional education exports and (as the Opposition parties might note) additional unpriced water pollution and methane emissions associated with the growth in agricultural exports.

Recall too that the whole logic behind the government’s export target was about closing some of those income and productivity gaps to the rest of the advanced world. As Mr Joyce noted elsewhere in that same interview “productivity has been a 30 to 40-year issue for New Zealand” (longer than that actually). One of the ways in which sustainable success of an economy tends to manifest is in the ability of firms based in a country to sell more stuff successfully abroad, enabling us to purchase more stuff from them.

In a post the other day, I highlighted our experience relative to a bunch of other countries that had been setting out to catch up, eight (now) fairly-advanced central and eastern European former communist countries.

Here is how (nominal) exports as a share of GDP have done in New Zealand and in those countries since 2007.

and here is a chart showing the gap between the growth rate of export volumes and the growth rate of real GDP (again, latest 12 months compared to calendar 2007).

And, drawing this towards a close, in case anyone was hoping (against hope) that the services sector might provide a more encouraging export story (death of distance as technology advances etc) here is the chart of how services exports as a share of GDP have done.

But no.

Were I trying to make a case for the defence, I would highlight two relevant considerations that Steven Joyce didn’t mention:

- first, the impact of the Canterbury earthquakes. Real resources have had to be used for the repair and rebuild process that simply couldn’t be used elsewhere (eg to build export industries), particularly as much of the cost was covered by offshore reinsurance (which gave people cash, but not more real resources to do the rebuilding with). As that phase passes, resources will be freed up and we might expect them to flow back towards the tradable sectors of the economy,

- second, the unexpected sharp and persistent reduction in interest rates which (for a country with a large private external debt) represented a considerable windfall. We have been able to consume more without having to produce (or export) more. It is a windfall, but in the longer-run it is no substitute for a policy climate that supports productivity growth and the growth in both the export and import share of our economy.

And, on the other hand, you might have noticed that I mentioned earlier that Israel had been somewhat like us. Exports as a share of GDP had fallen further than in New Zealand, and the terms of trade had increased over the last decade by about as much as New Zealand’s had. The other thing that constantly marks out Israel is the rate of population growth, from a mix of high (but falling) birth rates and high rates of immigration. Israel’s population has increased by just over 20 per cent since 2007 (New Zealand’s population has increased quite rapidly by international standard, but “only” by about 12 per cent).

Just like the earthquake story, real resources required to build the considerable infrastructure (houses, road, offices, factories, schools etc) associated with a rapidly growing population aren’t available for growing other industries. In New Zealand’s case that rationing process works through a persistently high real exchange rate and real interest rates persistently high relative to other advanced countries. I’ve written previously about Israel’s underwhelming long-term productivity performance, and suggest that, as with New Zealand, rapid population growth in an unpropitious location, has made it hard for firms based in either country to take on the world (economicially) and succeed. The experience of recent years – remember, no productivity growth at all in New Zealand for five years now – looks like another straw in the wind in support of that suggestion.

Relative to the government’s target, export performance in New Zealand has been poor. Relative to other advanced countries, it has also been poor. And all that notwithstanding very favourable terms of trade. Exports aren’t everything by any means, but the only OECD country in the last decade that has had a worse overall export performance than New Zealand and had a good terms of trade has been the one advanced country with a consistently faster rate of population growth. Export volumes have grown quite a lot in the last decade – just over 20 per cent – but they’ve barely kept up with overall GDP growth (in most countries, there has been much more export volume growth), and even then only through new subsidies (export education) and unpriced environmental externalities. It is a flawed strategy. And it is an unsustainable one.