Still working my way through the various articles and documents that turned up just before Christmas, I got to a lengthy issue of the Reserve Bank Bulletin, headed “Independence with acccountability: financial system regulation and the Reserve Bank”. It is, I suspect, designed to fend off calls for any significant reform.

The Bulletin speaks for the Bank, and although as I read through the article I noticed distinct authorial touches and tendencies, when all is boiled down the author was sent into the lists to make the case for how things are done now: powers, governance, and accountability. He does a pretty good job of presenting the party-line, against significant odds in many areas. Even where one disagrees with the Bank’s case, it is a useful and accessible addition, in part because the Bank’s powers and responsibilities in regulatory areas have grown like topsy over the years and are scattered across various pieces of legislation.

Much of the first half of the article is designed to make a case for an independent prudential regulator, by reference to the theory and to the writings of the Productivity Commission. But, for my tastes, it was far too broad-brush to add much value. Probably no one disputes that we want the rules applied fairly and impartially, with politicians largely kept out of the process. In the same way, we don’t want politicians deciding which person gets arrested and which not – we want an operationally independent Police for that – or who gets convicted – independent courts – or which airline passes safety standards and which not, and so on, so we don’t want politicians deciding to look favourably on one bank’s risk models and not on another’s. There are many independent regulatory agencies – or even government departments where the chief executive exercises responsibility in independently applying the rules – but to a very substantial extent they apply and administer the rules, while other people make the policy/rules.

The Reserve Bank wants to make the case that in its area the rules/policy shouldn’t be set by elected people (whether Parliament itself, or ministers by regulation), but by an independent agency, and that the same agency should both make and apply the rules (without any possibility of substantive appeal). It is the “administrative state” at its most ambitious – unelected officials (a single one at present, not even directly appointed by a Minister) are lawmakers, prosecutor, judge and jury (and quite possibly the equivalent of the Department of Corrections as well).

The Bank seeks to rest a lot on the notion of time-inconsistency, a notion from the academic literature that is sometimes used to try to explain the high inflation of the 60s and 70s, and to make the case for an independent central bank to make monetary policy. The idea is that even though one knows what is good in the long-run, the short-term benefits of departing from that strategy (and endless repeats of the short-term) mean that the long-term gains are never realised. The solution, so it was argued, was to remove the short-term management of the business cycle from politicians. I’m not particularly persuaded by the model as it applies to monetary policy (a topic for another day), and it is curious to see a central bank putting so much weight on that model after year upon year of inflation below target. But today’s topic is financial regulation and financial stability, where the Bank would have us believe it is desirable/important to have the rules themselves – the policy – set by someone other than politicians.

No doubt it is true that there can be some tension between the short and the long-term around financial stability. But that is surely so in almost every area of government life and public policy? Underspending on defence now frees up more resources for other things now, but one might severely regret doing so if an unexpected war happens later. Skimping on educational spending now won’t make much difference (adversely) to economic performance or the earnings of anyone (teachers aside I suppose) for a decade or two. Running big fiscal deficits now can offer some short-term benefits, but at the risk of heightened vulnerability etc a decade or two down the track. But in none of these areas do we outsource policymaking: they are political choices, and we then employ officials and public agencies to administer and deliver those choices. The Reserve Bank has, as far as I’m aware, never offered any explanation as to what makes their specific area of policy different. Sometimes they draw on academic authors writing about financial regulation, but many of those specialists fall into the same trap – they see their own field, but never stand back and think about how democratic societies organise themselves across a wide range of policy.

As it happens, the current system around the Reserve Bank and financial regulation is a bit ad hoc and inconsistent to say the least, a point that the article more or less acknowledges. Thus, for banks the Reserve Bank can vary the “conditions of registration” to change all sorts of big policy parameters, without any formal involvement from elected politicians at all (all the variants of LVR policy, from the first Wheeler whim were done this way). But even for banks rules around disclosure have to be done by Order-in-Council, and thus require ministerial approval. No one would write the law that way – such different regimes for two different aspects of bank regulation – if starting from scratch (the actual legislation has evolved since 1986).

For insurance companies, the Reserve Bank itself can issues solvency standards (effectively, capital requirements for insurers), but for non-bank deposit-takers capital rules (and other main prudential controls) can only be set by regulation, again requiring the involvement and approval of the Minister of Finance. (Incidentally, this is why LVR rules apply to banks but not non-bank deposit-takers: Wheeler could regulated banks directly, but couldn’t do the same for non-bank deposit-takers.

(And, as the Bank notes, it has “no direct role in developing rules associated with AMLCFT”, even though it administers and applies those rules for banks.)

At very least, there would appear to be a case for streamlining and standardising the procedures for setting the rules. It isn’t clear why the Reserve Bank Governor should have almost a free hand when it comes to banks, but such limited scope to set policy when it comes to non-bank deposit-takers. And, if anything, the case for ministerial involvement in settting the rules for banks is greater than that for the other types of institutions because (as the Bank acknowledges) bailouts and recessions associated with financial crises etc have major fiscal implications, and one might reasonably expect elected ministers to have a key role in setting parameters that influence the risk of systemic bank failures. And, again as the Bank acknowledges, it isn’t easy to pre-specifiy a charter – akin to say the Policy Targets Agreement – for financial stability policy.

The Bank attempts to cover itself against suggestions that it might be, in some sense and in some areas, a law unto itself, by highlighting various ways in which the Minister of Finance might have some say. There are, for example, the (non-binding) letters of expectation, the need to consult on Statements of Intent, and the potential for the Minister to issue directions requiring the Bank to “have regard” for or other area of government policy. These aren’t nothing, but they aren’t much either – and as the Rennie report noted, the power to issue “have regard” directions has never been used. Even budgetary discipline is so weak as to be almost non-existent: there is a five-yearly funding agreement, but it isn’t mandatory (something that needs fixing in the current review), isn’t particularly binding, and doesn’t control the allocation of spending across the Bank’s various functions. The Minister of Finance doesn’t even get to make his own choice of Governor – and all Bank powers still rest with the Governor personally.

The contrast with the other main New Zealand financial regulatory agency, the FMA, is pretty striking. Policy is mostly set by the Minister (by regulation), advised by MBIE (to whom the FMA is accountable), and the powers of the organisation itself rest with the FMA’s Board, all the members of which are appointed directly by a Minister, and all of whom – under standard Crown entity rules – can be removed, for cause, by the Minister. Employees, including the chief executive, only have powers as delegated by the Board. The FMA model is now a pretty standard New Zealand regulatory model, and an obvious point of comparison with the Reserve Bank.

Somewhat cheekily, the Reserve Bank attempts to present their own model as providing more scope for ministerial input than for the FMA (see footnote 16, in which they note that for the FMA there is no power of government direction). As regards policy, it isn’t necessary, since the government sets policy and appoints (or dismisses) the Board. As regards the application of rules, one wouldn’t want – and doesn’t have – powers of government direction in either case. As regards the banking system, mostly ministers can’t set policy, can’t hire their own Governor, and can’t fire him (re financial system policy) either. The Governor and the Bank have far more policy power than is typical – across other regulatory agencies – appropriate, or safe.

The second half of the article is about accountability. As they reasonably note, when considerable power is delegated to unelected agencies, effective accountability needs to provided for. In their words “accountability therefore generates legitimacy and legitimacy in turn supports independence”.

It is, therefore, unfortunate that the Bank’s very considerable powers are matched, in this area in particular, by such weak accountability. After pages of attempting to explain themselves and what they see as the various aspects of accountability, even they end up largely conceding the point. These sentences are from the last page of the article

the BIS (2011) argues that financial sector accountability mechanisms should be focussed more on the decision making process rather than outcomes per se. This is because of the more intrusive nature of financial sector policy, and the issues associated with observing outcomes (lack of quantification and very long lags). Put another way, there should be less reliance on ex post accountability mechanisms and more obligations placed on ensuring decision-makers are transparent about the basis for their actions.

I’m not sure I entirely agree – although there is certainly the well-recognised point that absence of crisis is evidence of nothing – but at very least a focus on strong process might argue for:

- a more effective separation between policymaking and policy administration (as is customary for many regulatory entities, but largely not for New Zealand bank supervision),

- a decisionmaking structure in which power did not rest simply with a single individual, who is himself not directly appointed by an elected person,

- decisionmaking structures that involve real power with non-executive decisionmakers,

- effective and binding budgetary accountability,

- a high degree of commitment to transparency and to ongoing external engagement,

- a culture that is self-critical and open to debate,

- perhaps some more effective scope for judicical review (including on the merits, rather than just process),

- monitors with the expertise, mandate, and resources to ask hard questions and to critically review and challenge choices being made around policy and its application.

At present, as far as I can see, we have none of these for the Reserve Bank of New Zealand as financial regulator.

Take the formal monitors for example. Parliament’s Finance and Expenditure Committee has little time, no resources, and little expertise. The Treasury has no formal role, no routine access to Bank materials (or eg Board papers) and is probably quite resource-constrained in developing the expertise.

And what of the Bank’s Board? By law, they play a key role, as agent for the Minister of Finance in monitoring the Governor, and (now) obliged to report publically each year on the Bank’s performance. The Bank often likes to talk up the role of the Board – doing so provides them cover, suggesting the presence of robust accountability – but the latest article is surprisingly honest. The Board gets a single paragraph, which simply describes the legislative provisions. There is no suggestion of the Board have actually played a key role in holding the Bank (Governor) to account – not surprisingly, since in the 15 years they have been publishing Annual Reports, there has never been so much as a critical or sceptical word uttered. Of course, it isn’t surprising that the Board doesn’t do a good job: it has no independent resources at all (even its Secretary is a senior Bank staffer), the Governor himself sits on a Board (whose main role, notionally, is to hold the Governor to account) and the Board members themselves typically have little expertise in the areas (quite diverse) around which they are expected to hold the Governor to account for. (Their job is, of course, made harder by the rather non-specific mandate the Bank has in regulatory areas – there is nothing akin to the Policy Targets Agreement (which has its own challenges in monitoring).)

What of some of the other claims about accountability? The Bank points out that it is required to do regulatory impact assessments – but these are typically done by the same people proposing the policies, and there is (or was when I was there) nothing akin to the sort of process some government departments have for independent panels vetting the quality of the regulatory impact assessments.

They are also required to consult on regulatory initiatives, and must “have regard” to the submissions. But, except perhaps on the most technical points, there is little evidence that they actually do pay any real heed to submissions. For a long time, they also kept the submissions themselves secret – even attempting to claim that they were required by law to do so. They’d publish a “summary of submissions”, which highlighted only the issues they themselves chose to identify. As they note, and in a small win for a campaign by this blog, they have now started publishing individual submissions, belatedly bringing them into line with, say, Select Committees of Parliament or most other regulatory bodies. But there is no sign of much change in the overall attitude, or of any greater openness to ongoing debate and critical scrutiny.

Then, of course, there is the Official Information Act. The Bank is subject to the Act, but chafes under the bit, is very reluctant to release much, threatens to charge requesters, and generally seems to see the Act as a nuisance, rather than an integral part of an open and accountable government.

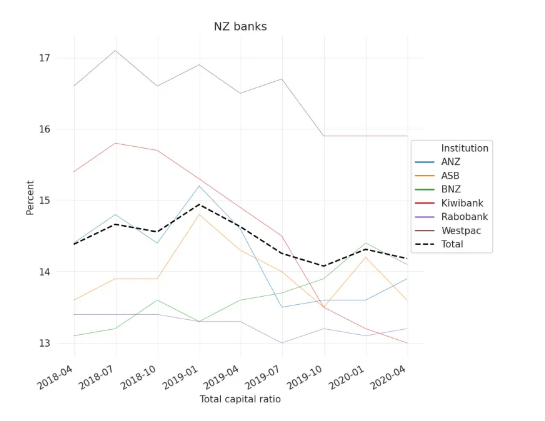

We had a good example just a couple of months ago as to how unaccountable the Bank is in its prudential regulatory areas. It emerged that Westpac had not had appropriate regulatory approval for some model changes used in its risk-modelling and capital calculations. But, as I noted at the time, the short Bank statement left many more questions than it answered, and no one – including journalists asking directly – has been able to get straight answers from them, even though capital modelling is at the heart of the regulatory system.

And, of course, if the formal monitors are lightly (or not at all) resourced, there isn’t much other sustained scrutiny. Banks are scared – and more – to speak out: this is where culture matters a great deal, as banks will always have a lot of balls in the air with the regulator, and in an open society should feel free to openly challenge the regulator, without fair of undue repercussions. Academics with much expertise in the area are thin on the ground, as are journalists with the time or expertise.

Mostly, in its exercise of its extensive financial regulatory powers, our Reserve Bank isn’t very accountable at all. Providing it jumps through the right, minimal, process hoops it can do pretty much what it likes in many areas of policy, and the public is left just having to take the Bank’s word (or not) that things are okay. That needs to change – and thus phase 2 of the current review of the Bank’s Act needs to be taken seriously. Making the changes isn’t about one single measure, and there are plenty of details that will take a lot of work, and thought, to get right. Part of it is about building a better internal culture, one that (from the top) really wants to engage, and which welcomes challenge and critical review.

After yesterday’s post I had an email from a reader with considerable senior-level experience in the banking sector noting just how weak much of the formal scrutiny of the Bank is in these areas.

From my perspective the Bank would benefit from independent challenge about their prudential responsibilities, and cost-benefit analysis. I am unsure if they have reviewed this post the Westpac capital model issues.

I am unsure how the Board discharges the independent prudential review role effectively given their experience – two Directors have insurance experience and no directors have Banking, payments system or other non-bank financial experience. Likewise experience of Insurance/Banking/Payments technology systems and risks. While there are some very good RBNZ executives they are not particularly strong in banking risk experience – funding, liquidity, credit etc.

…. I think it would be useful for the RBNZ at a governance level to have experience of how financial balance sheets, and liquidity operate under stress, they will have some very important decisions to make when the next financial crisis occurs.

Much of that rings true to me. We have typically had Governors with more experience of macro policy, and perhaps financial markets, than of banking – and yet financial regulation is a hugely important role in what the Bank does – and now have a new Head of Financial Stability with no background in banking or finance at all. We have a Board responsible for monitoring the Bank across monetary and regulatory responsibilities, and with little specialist expertise. The contrast with, say, the FMA is quite stark.

Quite what the right balance of a solution is, I’m not quite sure. I favour moving to a committee-based decision-making structure, and moving more of the policy back to the Minister (with the Bank as a key adviser), but even a Financial Policy Committee might only have three or four externals on it, and no such group is going to encompass all the right bits of expertise. As often, I guess it is partly about the willingness to ask the hard questions, and to be willing to commission independent expertise (whether from New Zealand or abroad, from academics or people with industry background) and to engage. If the Board remains as a monitoring agency – as Rennie recommends, but I’m sceptical of – it needs to be provided with resources. And the Minister needs to be willing to use his statutory powers to commission independent reviews of aspects of the Bank’s stewardship, to enable us (and the Bank) to learn from experience by critically evaluating performance (and process). Personally, I’m still tantalised by the idea of a small independent agency resourced to pose questions, and commission research, on the stewardship of fiscal, monetary and financial regulatory policy.

If not all the answers are clear, what is clear is that New Zealand is a long way from having got the model right: the right allocation of powers, the right accumulations of expertise in the right places, the right cultures, and the appropriate mix of formal and informal accountability that can really give New Zealanders confidence in the regulation of the financial system.

As he notes, the first four countries on the left of the chart couldn’t cope themselves and needed either IMF or EU support, and Spain also needed external assistance. But all these countries were in the euro-area, and thus not only lost the capacity to adjust domestic interest rates for themselves, but also couldn’t do anything to adjust the nominal exchange rate. By contrast, the UK’s bailout costs – not that much lower than Spain’s – never ever raised any serious questions about the UK’s fiscal capacity. And that was with a far higher starting level of public debt (as a share of GDP) than, say, Ireland had.

As he notes, the first four countries on the left of the chart couldn’t cope themselves and needed either IMF or EU support, and Spain also needed external assistance. But all these countries were in the euro-area, and thus not only lost the capacity to adjust domestic interest rates for themselves, but also couldn’t do anything to adjust the nominal exchange rate. By contrast, the UK’s bailout costs – not that much lower than Spain’s – never ever raised any serious questions about the UK’s fiscal capacity. And that was with a far higher starting level of public debt (as a share of GDP) than, say, Ireland had.

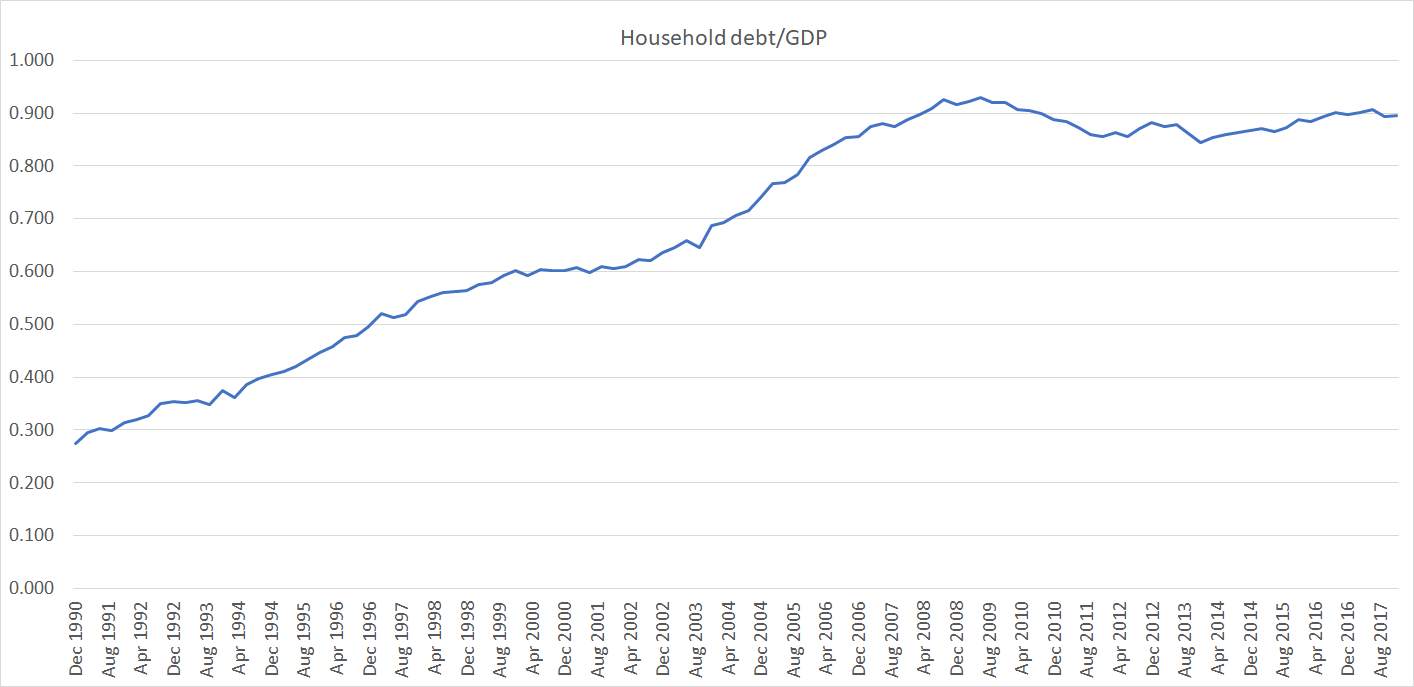

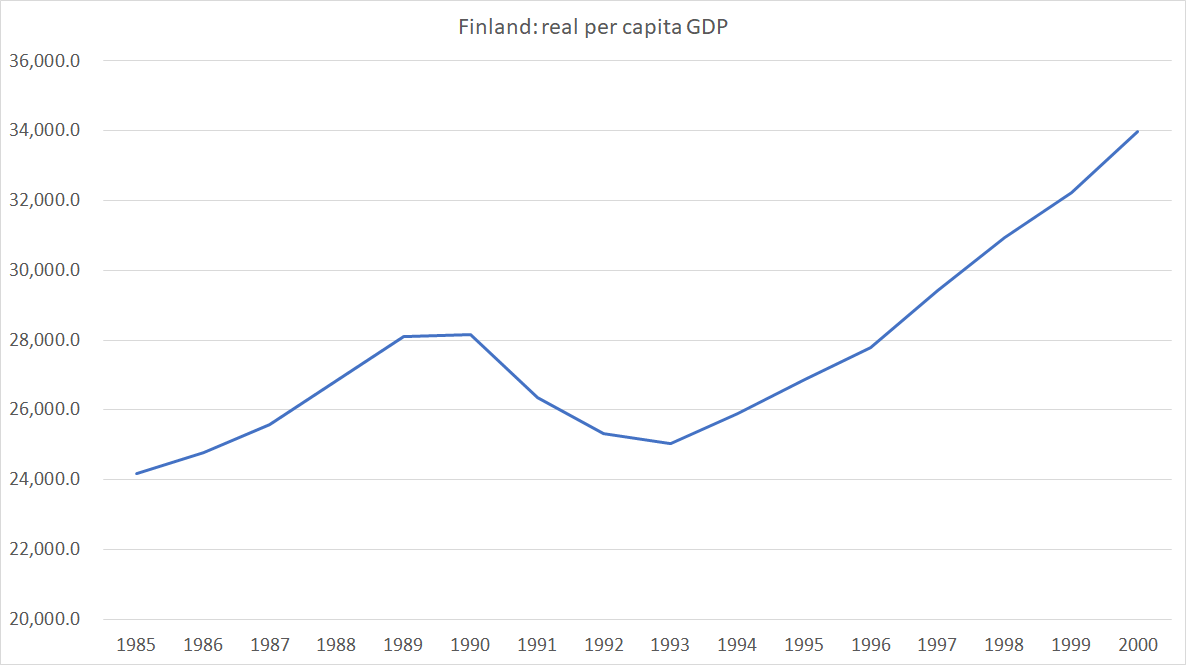

And consistent with a story I’ve run here in

And consistent with a story I’ve run here in