[An Australian website yesterday reproduced, without my permission, my entire post on the new government’s immigration policy, running it under the heading “Is Jacinda Ardern a fake?”. That heading does not – even in the slightest – represent my view. I’m assuming the new government will do as they said in their manifesto. And while I’m a bit sceptical as to how committed the new Prime Minister really is – the policy having been adopted under her predecessor and she never having talked about it in public fora – the point of the article was (a) that the policy itself does not represent any significant change in the likely future contribution of immigration to population growth, and (b) that various overseas commentators have taken the, quite clearly laid out, Labour policy as something much more dramatic than it actually is.]

A few weeks ago, my 14 year son, mad-keen on ancient history and starting to study economics as well, brought home from the library a book about the economy and society of ancient Greece. I’m not sure he read much of it, but I found it fascinating. Among the things I learned was that the ancient Greek states, Athens most notably, generally banned foreigners – even resident foreigners – from owning land. These states were typically actively engaged in international trade, and often encouraged foreigners with particular specialised skills to settle among them. So it clearly wasn’t an autarkic approach – some sort of isolation and national self-sufficiency.

But it caught my attention partly in the context of the change of government here, and the proposed new restrictions on non-resident foreigners being able to purchase existing dwellings. But the issue goes wider than that, and the ambivalence about foreign investment and foreign ownership of New Zealand assets dates back decades at least. And the Labour-New Zealand First agreement commits to

“strengthen the Overseas Investment Act and undertake a comprehensive register of foreign-owned land and housing”

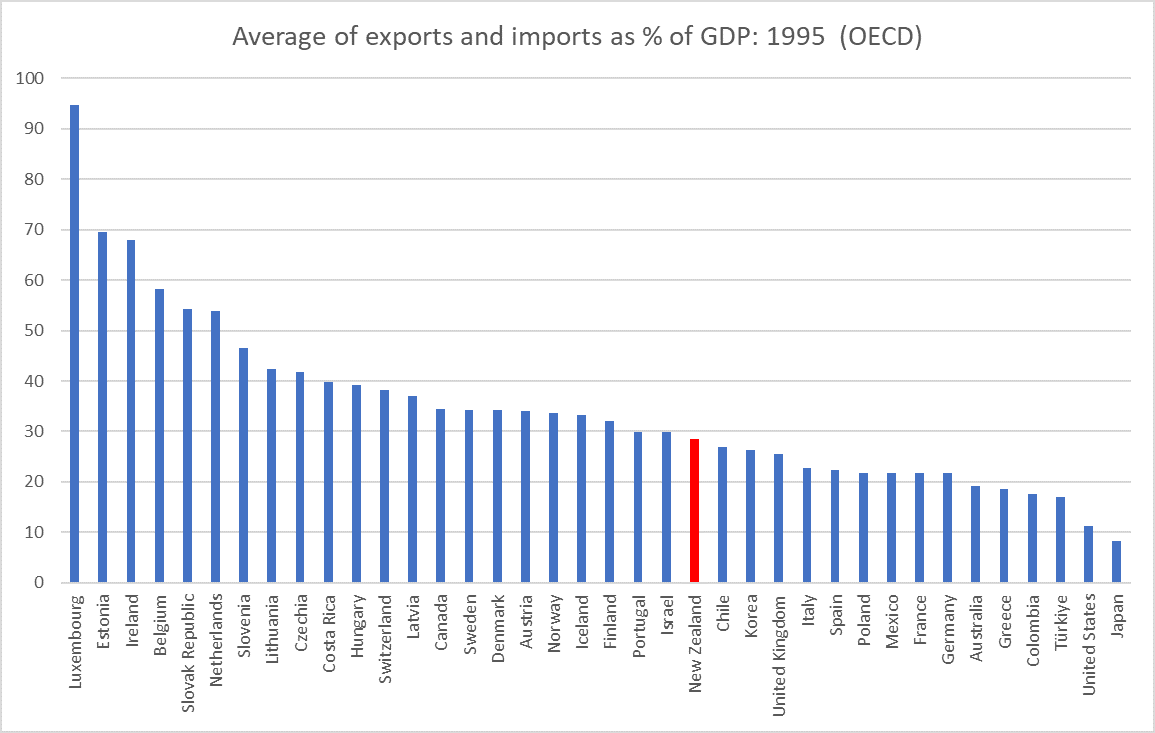

This in a country where the OECD already rates our existing restrictions on foreign investment as more severe than those of almost any other advanced country (even if there is some genuine debate about how restrictive our screening regime – what counts in the index – actually is).

Of course, the proposed ban (which could yet turn into a heavy tax, to get around FTA constraints) on foreign purchases of existing properties, isn’t really much of a ban on foreign ownership at all. Non-resident foreigners would be able to purchase a brand new house, with no particular restrictions, but not an existing house. Since new and existing houses are, to a considerable extent, substitutes – especially if you aren’t planning on living in the house – it isn’t even clear why the proposed ban would do more than throw a little sand in the wheels. And land-use restrictions have been the main source of driving house+land prices far beyond sensible levels – the best alternative use of those resources. So it isn’t clear why a restriction on non-resident foreign purchases of existing houses will do anything to lower the price (increase effective supply) of developable urban land. If governments can’t, or won’t, fix the land market, there might be more logic in a total ban on non-resident foreigners purchasing dwellings in New Zealand. Were there to be strong evidence of a significant effect on our market of such non-resident foreign purchases, I could see a reasonable second or third-best case for such a restriction. I’d prioritise the ability of our own people – immigrant or native – to buy a house+land over the freedom to sell to non-resident foreigners. That’s a value judgement, but one I’m comfortable with.

To be honest, I’m not sure what to make of the data we have. Lots of people are quite sceptical of the LINZ data, but I’m still struck by how high the non-resident numbers actually seem to be, at least in Auckland and Queenstown (the numbers are very small elsewhere). For the first six months of this year, almost 5 per cent of Auckland gross sales were to buyers wholly or partly non tax residents of New Zealand. In Queenstown-Lakes, the proportion was more than 10 per cent. There were non-resident sellers as well, of course. And some of those people (on both sides) were New Zealand citizens – eg a New Zealander who has settled in Australia, no longer treated as a tax resident of New Zealand, and a few years later sells a New Zealand property. But at a time when Chinese data show that capital outflows from China have hugely diminished

it is rather surprising how many purchases (net) were still being made by Chinese tax residents, even on the LINZ data with all its limitations. (In Auckland, net Chinese purchases make up more than the total net foreign purchases – ie people tax resident in other countries were net sellers.) And recall that China is the issue simply because the place is currently so badly governed – absent the rule of law – that its own people don’t feel safe keeping their money in their own country: we never had an influx of Japanese, French or British purchasers.

With a well-functioning urban land market, sales of houses/apartments to non-resident foreigners – even ones that just sat empty – could be just a modestly rewarding export industry. But we are a very long way from that sort of well-functioning market.

In Eric Crampton’s piece the other day, he highlighted that the proposed restriction would affect those here on work visas, as well as those who were not resident at all. If so, that was something I hadn’t realised. But his argument against drawing the line there wasn’t particularly persuasive

If someone is building a life here, it shouldn’t matter what visa they’re on.

But it does. If you are here on a student visa, or a temporary work visa, you might well hope you are now on a path to “a life here”. There might even, in some cases, be an implied expectation that that is how things will turn out. But New Zealand has not made a decision, at that point, to grant your wish. It does that only at the point where you get a residence visa (and then permanent residence). At that point we’ve said you can stay, but not before. If there is going to be ban or a tax, I don’t have a strong view on where the line should be drawn (there are avoidance issues wherever it is drawn). In practice though, not many people going to another country (or even another city) for just a couple of years will buy a house – the transactions costs are just too high – so if we are going to impose restrictions, I’m not convinced drawing the line in a place that banned those on temporary visas would be particularly problematic.

But restrictions on non-resident purchases of urban dwellings are mostly a second-order distraction from the real regulatory failures that have rendered house prices here – and in similar places abroad (eg Australia, UK, California) – so unaffordable.

Perhaps more sensitive, and more difficult, issues are around other foreign ownership issues. In reading around how they did things in Athens, I noted that foreigners might not have been able to own property, but they had the same access to the courts as citizens. These days, however, we – and many other countries – go one further and give foreign investors better access to dispute resolution than we provide to domestic investors, through the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) provisions included in numerous preferential trade and investment agreements, including TPP (and presumably the replacement for it, now close to finalisation). I wrote about these provisions back in 2015, quoting a writer for the New Yorker

“these provisions have been opposed by an unusual coalition of progressives and conservatives”

and a contributor to – not exactly left-wing – Forbes magazine that ISDS provisions represent a

“subsidy to business that comes at the expense of domestic investment and the rule of law”

In a country with a good quality legal system, it should simply be offensive and unacceptable that we provide foreign investors access to different courts and dispute settlement procedures, under different rules, than are available to domestic firms (even in the same industry). Equal status before the law is – or was – one of the cardinal principles of our democracy. At very least, citizens should always have at least as good rights as non-citizens or non-residents. (And that should apply to our citizens when operating in other countries, relative to the citizens of those countries – but that is an issue for those governments, not ours.)

What of the foreign investment itself?

There are easy cases, at either end of the spectrum. I don’t suppose anyone much is going to have a problem with a foreign investment fund owning an office block in Queen St. And I don’t anyone would have opposed restrictions if, say, the Soviet Union had found willing sellers for the whole of Stewart Island.

The hard stuff is where to draw the line between those extremes. There is a case – I think generally quite a good one – for a pretty relaxed view for most potential buyers and most potential assets. In part, that is a property rights view. If I own an asset and want to sell it, government restrictions on who can buy the asset lowers, probabilistically, the price I can command. It is, in the jargon, an uncompensated regulatory taking. Then again, a lot of the value of any (location-specific) asset arises from choices society has made collectively, about institutional quality, rule of law, good governance etc. Auckland airport, for example, wouldn’t be worth much if New Zealand were an ill-governed hell-hole.

There is also the argument that the New Zealand and, in time, New Zealanders generally will benefit most if the assets are owned by those best able to utilise them. When foreign investors bring technology or management expertise to a New Zealand industry or opportunity that isn’t as developed here, it is likely that in time there will be a wider benefit to New Zealand. That was how, for example, Tasman Pulp and Paper was set up, under government sponsorship in the 1950s. Or Comalco. (And, yes, I deliberately choose examples where there might be some doubts as to whether these firms should have established here in the first place.)

There are also diversification arguments. It bothers some people, but doesn’t really bother me, that most of our banking system is foreign-owned. There are some possible downsides – and we might have been better off if the foreign ownership was not so concentrated in Australia – but my reading of the international (and New Zealand) experience is that we are probably better off (more stable) for having a largely-foreign owned banking system.

There are also bureaucratic competence/incentives arguments. Our current overseas investment act in many cases requires demonstrating that a proposed foreign purchase would be “beneficial to New Zealand”. Beyond the evidence of, say, a foreign buyer being willing to offer the highest price, how comfortable can we be that officials and politicians have the ability or incentives to make those judgements correctly?

There are also arguments about debt vs equity. You might, in some cases, worry about control passing to foreign owners. But if domestic owners are reliant on lots of foreign debt there can be different, but at times more intense, levels of vulnerability. Debt can be called up, or simply not rolled over.

Foreign investment has played a significant part in New Zealand’s economic history, and its economic development. Sometimes in quite odd ways: the protectionist insulationist policies of post-war New Zealand encouraged quite a high degree of private direct foreign investment, as the most cost-effective way for foreign firms to get their products into the New Zealand market (inefficient and costly as it may have been for New Zealanders). But my reading of the New Zealand evidence and data is that foreign investment restrictions aren’t to any material extent what holds New Zealand’s productivity performance back. It is a more a case of there being too few good profitable new potential investment opportunities, whether for domestic investors or foreign.

None of this is really an argument for a laissez-faire approach, even if I’d still be more hands-off than most New Zealanders might. National cohesion and national identity aren’t easy to pin down, but are both real and important. And part of that – perhaps especially in a small country – is the control/ownership of land. I find it quite plausible that there might be international agricultural operators who could add new and different value to New Zealand operations through ownership and management of substantial parcels of agricultural land. But if, on the other hand, a growing number of wealthy offshore people simply wanted to own South Island stations and install local managers to farm much as they always have, I also don’t care very much if political unease is real enough that we end up simply saying “no” to such purchases on a large scale. Again, at an extreme, if non-resident non-citizen buyers ended up owning 80 per cent of the land in some locality – be it Northland or central Otago, or wherever – then I think we’d have undermined something about what it means to be New Zealand – given undue weight, including in local government, to the interests of people who aren’t part of this polity – in that area. A country is some mix of people in some specific place; a bundle of tangible people and land, not just an idea.

How real are those particular risks? I’m not sure – perhaps the new register will help give us a better sense. And there are plenty of countries – other open liberal societies – that place few or no restrictions on such purchases. But perhaps things are a bit different in a small country?

And then there are the national security dimensions, which seem to be treated too lightly here. A standard response is “but the local government can always regulate things” . I don’t think it is typically an adequate response if, say, a hostile foreign power owned key telecoms networks or ports/airports: regulation and governments just aren’t that good, and can also become too responsive to the interests of the overseas investors. Of course, confronting this issue also involves identifying the minority of countries that count as potential “enemies” and, on the other hand, which are countries where there is (a) a substantial commonality of interest, and (b) where investors can be reasonably assumed to be working in their own interests, not those of their home governments. At a time when the Soviet Army was just across the border, the West German government would have been crazy to have allowed Soviet interests to have purchased and controlled major West German infrastructure or technology assets. We’d have been crazy to sell Stewart Island to Soviet interests.

Today’s Soviet Union is China, with the difference that these investment hypotheticals are increasingly real, used as a direct means of extending political reach. That is nothing about race, and everything about (geo)politics. I don’t think that taking these issues and threats seriously means banning all, or perhaps even most, Chinese foreign direct investment. But it means a greater degree of realism, than tends to have pervaded recent governments, that their interests are not our interests, that all or most Chinese corporates are effectively under the thumb of the government and Party, and that not all voluntary transactions are likely to be beneficial for New Zealand as a whole even if they benefit both the buyer and the immediate seller.

There is no particularly strong conclusion to this post. Drawing appropriate lines – and translating them into legal rules – isn’t easy, and that is often a good reason for restraint. And yet neither is defining, or fostering and sustaining, nationhood. But that something is hard isn’t an excuse for simply ignoring the potential issues. Part of doing that well is perhaps first fostering a compelling and convincing sense that governments are governing in the interests of New Zealanders as a whole. Of course, different people will see those interests, and the policies that best serve them, differently – that’s politics. But finding the right answers – as perhaps around immigration – is unlikely to proceed best by simply exchanging slogans.