I watched the TVNZ Q&A interview with the Prime Minister yesterday. Apparently, the National Party has a widely-distributed brochure suggesting that interest rates are set to rise if the Labour Party takes office after the election. I haven’t seen the brochure, but the Prime Minister seemed determined to defend the claim, even as he had to concede that – of course – he couldn’t guarantee that interest rates would not rise over the next three years if his own party was re-elected. When pushed, his claim seemed to reduce to the proposition that interest rates were more likely to rise, and perhaps might rise more, if Labour was in office.

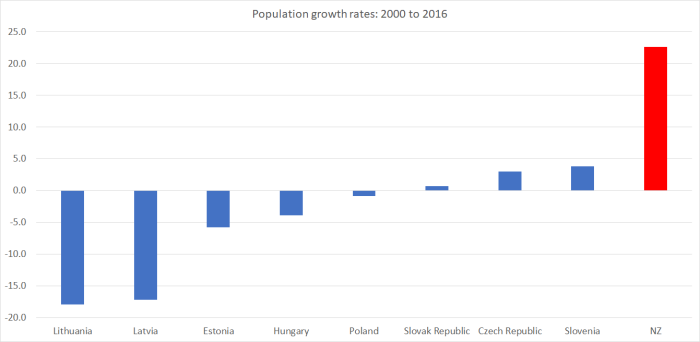

I know that a lot of people now have a lot of debt, and most New Zealand loans reprice pretty frequently (floating rate or short-term fix). But no serious person will argue that interest rates are quite low at present because the economy is doing well. Market interest rates around the advanced world (and central bank policy rates) have been very low for some years now, despite all the public and private debt, because demand (real economic demand) at any given interest rate isn’t what it was. Population growth has slowed in most countries (not New Zealand of course), productivity growth has slowed, and there just don’t seem to be the number of profitable investment opportunities there were. Globally, higher interest rates would, most likely, result from some improvement in the medium-term health of the economy. That would be true here as well (with the caveat that ideally one day some government would make the sorts of policy changes that would allow the persistent gap between New Zealand and “world” interest rates to close.)

But the Prime Minister’s claims about interest rates were also odd because:

- actual retail interest rates (those ordinary people pay and receive) have been rising over the last year, and

- both the Reserve Bank and The Treasury have official published projections showing policy interest rates rising over the next three years.

The increases in actual interest rates over the last year havn’t been large (about 25 basis points for floating rates, and something less for deposit and business overdraft rates). But as we’ll see, those are large changes compared to the sorts of effect the Prime Minister seemed to be talking about.

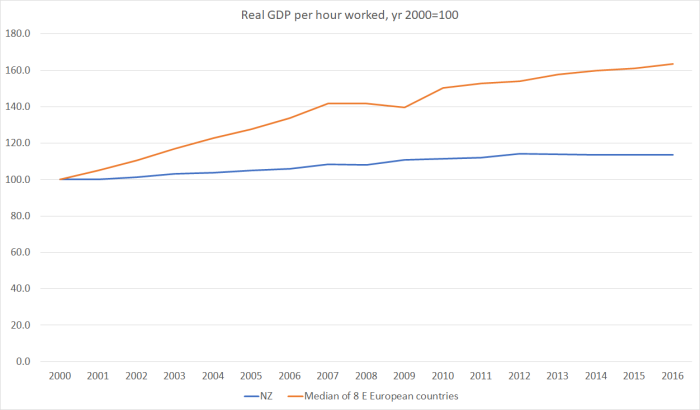

And what about the next few years, on current policies (monetary and fiscal)? These are the projections from the latest Reserve Bank Monetary Policy Statement and from The Treasury’s PREFU.

The Reserve Bank doesn’t expect much of an increase in the OCR over the next three years, but it is an increase nonetheless. The Treasury seems quite gung-ho – by the time of the next election, they expect we’ll have seen 150 basis points of interest rate increases. I suspect that Treasury’s numbers are too high, but both sets of projections are (a) upwards, and (b) well within the historical margins of uncertainty. Neither agency gives enough weight, at least in what they are saying in public, to the possibility – again well within historical bands of uncertainty – of materially lower interest rates. It seems unlikely that the Prime Minister would welcome a world in which such interest rate cuts were required.

The Prime Minister’s specific claim seemed to be that the Labour Party’s fiscal policy would result in higher interest rates than the fiscal policy adopted by the National Party. He attempted to muddy the water with talk of what any Labour coalition parties might demand, but of course on current polling it seems likely that any National-led government would also have to face coalition party demands. So, for now, lets just focus on actual main party plans – National’s as per the PREFU, and Labour’s as per their published fiscal plan.

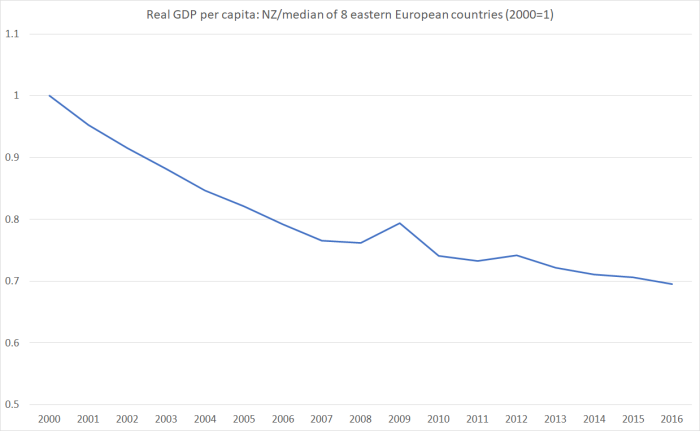

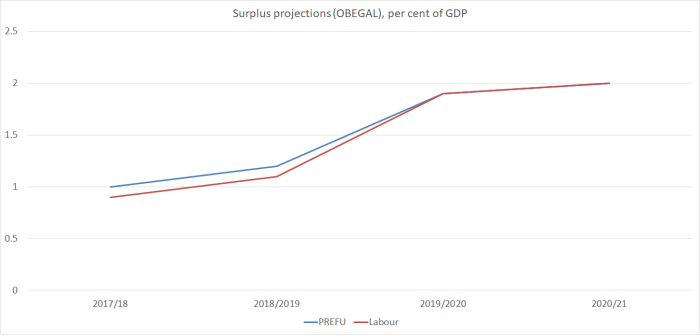

There would seem to be two plausible channels through which fiscal differences might mean different interest rates. The first would be if Labour was to run materially lower surpluses, or even deficits. The increased demand that would flow from those annual spending or revenue choices might, all else equal, lead the Reserve Bank to raise the OCR. But here (as I’ve shown before) are the two surplus tracks.

They are all but identical, especially when one bears in mind that the Reserve Bank is typically looking a couple of years ahead in setting interest rates. If Labour does take office, no Reserve Bank Governor – acting or otherwise – is going to be looking at that track, with a slight difference in 2018/19 and none beyond that – and altering his or her interest rate projections.

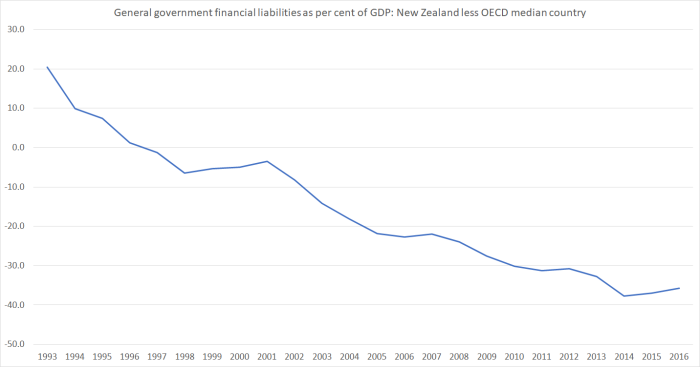

The other channel is through a stock effect; the effect of a higher accumulated stock of debt. The Minister of Finance has attempted to highlight that Labour’s plans involve around $7 billion more of net core Crown debt in 2020/21. Sounds like a lot of money. In fact, the difference is 2.2 per cent of GDP. And around half that difference doesn’t show up in a true net debt series (such as that reported by the OECD) at all: it is the additional $3 billion of contributions to the NZ Superannuation Fund. I don’t happen to think that resuming those contributions is particularly sensible, but both main parties do – their only difference is timing – and if contributions to the NZSF add a bit more risk (variability) to the Crown balance sheet, they don’t make us poorer. It is very very unlikely that raising a little more gross debt to put money in an investment fund like the NZSF will have any effect at all on New Zealand retail interest rates.

But what does the research show? Disentangling the determinants of New Zealand interest rates isn’t easy, and I’m not aware of (m)any new studies over the last decade or so. But a couple of prominent New Zealand economists did some interesting modelling work on the issue back in 2002, for Westpac. Adrian Orr is now head of the NZSF – and perhaps a contender for being the next Governor – and Paul Conway is head of research for the Productivity Commission. They looked at the impact of net government debt (not idiosyncratic national definitions, but drawing from international databases), and this is what they found

Table 2 shows the marginal and total impact of government debt on real bond rates. Moving from a net debt level of 10% of GDP to 20% of GDP adds only 3bps to real rates and the total contribution of debt to the risk premium is only 6.5bps.

As one might expect, the effects were quite a bit larger when debt levels were a lot higher than they are in New Zealand.

On these internationally comparable net debt measures, current net government debt in New Zealand is about 9 per cent of GDP, and on both National’s plans and Labour’s will fall from here. Labour reduces public debt a bit less than National does over the next few years, but recall that by 2020 even on the Treasury measure of net debt the difference was 2.2 per cent of GDP. Applying the Orr/Conway model results (that 6.5bps for 10 percentage point change in debt), and even that increase will produce only around a 1 basis point change in interest rates (with significant margins of uncertainty around those estimates). And these are long-term government bond rates they were modelling. Any effect on short-term retail rates – probably zero – would be indiscernible.

Are they other possible differences in interest rates that might show up depending on who wins the election? These ones occurred to me:

- both parties, but perhaps particularly Labour, look likely to have some difficulty keeping to their announced spending plans in the next few years, given baseline cost and population pressures and the recent electoral auction. Whether that would result in smaller surpluses depends on what other offsetting actions respective governments might take (and, of course, what happens to revenue flows).

- one reason why Labour’s net debt numbers are a bit higher than National’s is Kiwibuild. In the Labour fiscal plan, they allow $2 billion of new and additional debt to get the Kiwibuild programme going (intending to roll that forward as new houses are built and sold). I suspect that much of the Kiwibuild activity will displace private sector construction, but if it doesn’t – and it actually adds to total construction activity – that would put more pressure on available resources and – all else equal – increase the chances of OCR increases in the next few years. But since both sides agree that more houses need to be built, it is hard to see how either could describe any such increase in the OCR as a bad thing – if anything, in their own terms, it would be a mark of success.

- Labour is talking about reducing net immigration inflows. I’m a bit sceptical as to whether they would carrry through on that, given the evident decision to downplay the issue since Ardern took over. But if they do follow through, there would be a reasonably material reduction in overall demand and resource pressures over the next 12-18 months (especially as their proposed cuts are focused on the student sector). All else equal, that would reduce the chances of OCR increases in the next couple of years.

- Labour is promising Reserve Bank reforms. Much is likely to depend on the key individuals they appoint, but – all else equal – their proposal to add an unemployment objective would be likely to reduce the chances of near-term OCR increases. (In the longer-term there is a risk, that would have to be managed, that such a reform could slightly increase longer-term inflation expectations, and thus the level of nominal interest rates.)

In the end, this is fairly silly debate. The differences in fiscal policy are small, and the track record of the two main parties over 30 years now is of pretty responsible fiscal management. Debt levels are low and, absent a severe crisis, near-certain to remain so.

And interest rates do move around. In well-managed countries they most often rise when economies have been doing pretty well, and they fall when something bad happens. What will determine what happens to interest rates – market and official – over the next three years? It won’t (overwhelmingly) be our choice of Prime Minister, but – in the famous phrase of Harold MacMillan, former British Prime Minister – “events, dear boy, events”.

And we, they (politicians) and the Reserve Bank should fear the sort of events that could yet take our interest rates quite a bit lower than they already are.