There is an extraordinary column in the Herald this morning, by their excellent Kate MacNamara (complete with nice biblical allusions in the online version headlines, which may be lost on a younger generation of readers) on the travails of the Productivity Commission. If you can get access, and you care at all about economic policy and institutions in this country, you really should read it.

The Productivity Commission was set up a decade or so ago by the previous government. Inspired by the Australian Productivity Commission – which has done some good work over several decades – there were both cynical and genuine motivations behind it. On the cynical side, it was a cheap win for ACT (this was during the 2008 to 2011 term), and it offset the premature termination of the 2025 Taskforce. But on the more serious side, there was a recognition of the long-running New Zealand productivity failures, and a genuine recognition of the contribution of the Australian commission. There was, of course, no willingness by either the previous government or the current one to do anything serious about productivity-enhancing reform, but perhaps a small fairly inexpensive Commission might come up with some useful nuggets.

One can debate what value the Commission added in its first decade (a mixed bag on my telling), but this story starts 18 months or so ago when the government appointed Ganesh Nana as the new chair. Things seem to have gone dramatically downhill from there, and article reports several waves of staff departures, as well as reminding us of the departure of two commissioners (so bad has the government’s handling got, that one commissioner has had to agree to stay on a bit just so that the Commission has a quorum). Independent HR consultants had been hired (MacNamara got their report) and she has various staff (former and, quite probably, current) speaking to her. The Productivity Commission (PC) is a small organisation, and must be an even more unhappy place this morning.

Nana was clearly appointed by the Minister of Finance to bring a quite different ideological (charitably, analytical) approach to the Commission, but surely even Robertson must be surprised at how poorly Nana has handled the transition from running his own consultancy, to leading an established public sector agency. Some cynics reckon the intention all along was to gut the Commission. Perhaps, but state-funded commissions producing ideologically sympathetic – but perhaps good quality – reports have value to political parties, and it seems they probably aren’t even getting that. Instead, following on from the systematic degradation of the capability of the Reserve Bank, Robertson now seems to have done it to the Productivity Commission as well. Both have the hallmarks of a man who openly says he went into politics to be not Roger Douglas, and who really cares barely at all for the longer-term capability of our economic agencies, let alone the longer-term performance of the New Zealand economy.

But the main reason for this post was that I got mentioned in the article, in a way that may read a little unfairly to Nana (of whom I have been consistently critical since he was appointed, and whom I do not think is fit to hold that particular office). The context was the recent immigration inquiry.

First, it should be noted that the Productivity Commission, as is usual, invited submissions from anyone on both their issues paper and their draft report. I did not make a submission in the first round (although I did make a fairly short submission on the draft report) and, as far as I can recall, neither Eric nor the New Zealand Initiative made submissions at all. I did not make an initial submission for two reasons: first, that my views had long been on the record (and I knew Commission staff were aware of papers/speeches) but also because I had little trust in the willingness or ability of the Commission to grapple seriously with the analytics of the New Zealand experience with large scale policy-led immigration. Among other things, several years earlier Nana had openly championed a “big New Zealand” model in an RNZ discussion we had both participated in.

However, over the course of last year there were several interactions. In June, Commission staff invited me in to articulate my story (which had been outlined again in a recent speech) and to offer any perspectives on the Issues Paper they had released. I had a session at the Commission on 8 July where I noted (my diary)

…to my slight discomfort [given my past open criticism of him] even Ganesh turned up. Seemed to go quite well – Bill Rosenberg in particular quite tantalised – and I think I at least got them to the view that some sort of cross-country and historical analysis will be needed to do the job even remotely well.

I followed up the meeting by sending them a series of further observations, links to posts etc.

Several weeks later I had this unprompted email from a senior Commission staffer, cc’ed to the inquiry director

I wasn’t keen, for various reasons

Despite my expressed reluctance, Commission staff pursued the matter, and I had a phone discussion with Geoff Lewis. My diary records

Talked to Geoff Lewis about the paper the PC want me to write. I’m not keen – don’t think it would work for them or me (or my cause) – but Geoff has gone to sound out Graham Scott [former Commissioner] & might see if they can get parallel papers from Eric and me – which could work.

I don’t have records of this, but memory suggests it being mentioned at some point that Scott had shared my doubts. I don’t know whether staff ever approached Eric, but as you can see I was never keen, and frankly had I been Ganesh Nana I probably wouldn’t have been keen either. (Note that the views of both Eric and I on New Zealand immigration policy and economic performance were already well-documented in various references, speeches etc, including a couple in which we had shared a platform.)

But that wasn’t the end of my engagement with the Commission (staff or commissioners).

And we had that session on 1 October. From memory all the Commissioners attended, and most of the Commission staff. Arthur Grimes is pretty open about his general sympathy for an open-borders approach, and a big believer in large scale immigration to New Zealand (telling the Commissioners that the big gain from immigration was the higher house prices existing New Zealanders got to sell their houses at). Despite our vast differences on the wider issue, Arthur and I combined to strongly disagree with the suggestion the Commission was floating for trying to calibrate the non-NZ citizen inflow to changes in the net flow of NZ citizens. It was a simply unworkable scheme, even if in principle it had had any substantive merit (which I suspect neither of us thought it did).

I concluded my diary comments observing that

But the real problem is that not really any of the Commission people had a strong macro orientation and so much of the discussion appeared ill-anchored (and often not that aware of other experiences etc etc),

Ganesh Nana’s own comments and observations was particularly superficial. Staff seem to have had good intentions, but not necessarily the capability, and the Commission as a whole seems not to have been willing to hire or contract relevant expertise

Obviously I cannot speak to what was going on inside the Commission’s four walls, but I will give Nana credit for having turned up to both meetings.

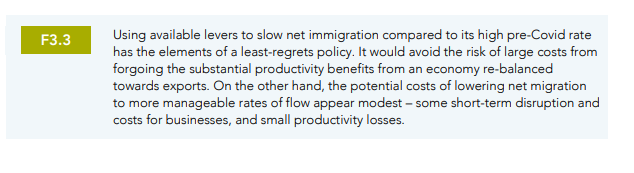

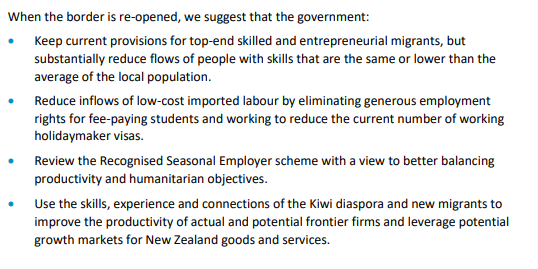

The Commission’s draft report was released in November. It was a dog’s breakfast, and thus suggestive of real tensions with the Commission. I wrote about the draft here under the heading “Productivity Commission at sea”.

In a background paper there was a reasonable discussion of aspects of what has become known as “the Reddell hypothesis”, but you would hardly have known it from the main draft report

As for the “Reddell hypothesis” itself , the Commission says

At this stage of its inquiry, the Commission is not taking a definite view on the Reddell story

Which, I suppose, is a legitimate stance for them to take, but there is nothing much in the report even indicating where their key uncertainties are, let alone a provisional overall interpretation that submitters could scrutinise and review. I don’t suppose that will seem very satisfactory to anyone, from any side of the debate, considering making a submission. It speaks of a Commission that just has not exercised the intellectual grunt to critically analyse, assess, research and review conflicting arguments and interpretations.

There seemed to be both weaknesses in analytical grunt, and the likelihood of disagreements within the Commission, and yet there was no sign of any serious effort to get to the bottom of the issues. It might have been an entirely reasonable conclusion, having thought hard about the New Zealand experience (past and present, abstractly and in light of literature of other countries’ experiences), that they could show that large scale immigration had in fact produced substantial economic gains for New Zealanders. Or to have become persuaded by something akin to my story. But they never showed any sustained sign of making the effort, either way.

I did make a submission at this point (link in this post), partly for the record and partly to back up a couple of other submitters (one of whom was running more or less my story).

In many respects, the final report was even worse than the draft. It was more or less devoid of any serious analysis of the economic implications of New Zealand’s experience with large scale policy-led non-citizen immigration. Even for those of a serious analytical bent who basically like something like the pre-Covid status quo, it can’t have been at all satisfactory – making no attempt to do anything more than offering up quite glib lines about there being small economic benefits from the New Zealand policy approach. Understanding was not advanced one jot – fallacious stories (whether mine or the policy-establishments) are not shown to be wrong, true stories (whichever) have no serious evidence advanced, or fresh analysis undertaken to strength our confidence in those stories.

It was, in the words of a former Treasury deputy chief economist (not at all sympathetic to my specific story) on Twitter the other day, the sort of thing one might easily have gotten an MBIE policy team to churn out: a few charts, a few bromides, a few minor bureaucratic recommendations, and no real added value – from an independent Productivity Commission – at all. Whether one is inclined to agree with their prejudices or not.

For me, it was perhaps summed up in a lunchtime seminar a couple of weeks back organised by Motu on the Commission’s report. The speakers/panellists were all pretty keen on large scale immigration to New Zealand, but what really caught my ear was Nana who (a) wanted to take politics out of immigration policy (what planet is he on, for such a significant structural policy choice) and (b) describing any doubts about a large scale policy-led migration to New Zealand could only sneer that any scepticism reflected a concern about “nasty migrants”.

And that sort of summed up a deeply inadequate inquiry from a seriously inadequate Commission.

The Productivity Commission should simply be wound up. It adds no obvious value and can never have the institutional depth and specialisation of the Australian version. It isn’t obvious that either Labour or National want serious rigorous in-depth economic analysis and research, but if they do we might as well concentrate public sector resources at The Treasury, who are supposed to be the government’s main advisers on such things.

In the meantime, you wonder which left-wing economists the government will eventually persuade to take on a Commissioner role, especially under Nana.