It must be quite a challenge for Rotary clubs to maintain a regular roster of speakers. Four years ago someone at the Wellington North Rotary Club had heard about my ideas on immigration policy and New Zealand’s lamentable economic performance and they invited me along to tell my story. The text I used then is here. A little while ago they invited me back and when we discussed what I might talk about I agreed to pick up where I’d left off in 2017 – at the very peak of the then immigration surge – and reflect on a better immigration policy for New Zealand as and when the borders eventually reopen (in the year to April, SNZ estimates a net outflow of about 9500 non-New Zealanders who’d been here for some substantial period of time.

So I spoke to them yesterday. One can’t cover everything – or even anything much in the depth the subject warrants – in 20-25 minutes, but for those interested my text is here.

Sadly, of course, the stylised facts of New Zealand’s economic underperformance haven’t changed for the better over the intervening four years. Productivity levels remain low and growth weak. Business investment has been pretty sluggish around low rates, and if anything the export/imports shares of GDP have probably fallen a bit more (even before Covid at least temporarily cut both further). Our real exchange rate stayed high, and if long-term real interest rates have fallen they were/are still well above those in almost all other advanced countries.

What has changed, for now anyway, is the substantially closed borders, which mean that it is very hard for most non-New Zealanders (Australians aside) to get in. No one envisages, or wants, current arrangements – or anything like them – to be permanent, but it does mean the conversation and debate starts from a rather different place than it might have a few years ago.

Perhaps what hasn’t changed so much is that much of the media debate – and apparently the political interest – seems to be on short-term visa holders. And almost every day now we hear stories from employers complaining about how hard it is to get staff, holding the border restrictions responsible.

It isn’t surprising that there has been some dislocation, disruption, and difficulty for some firms. After all, the borders were basically closed overnight, for public health reasons, and that disrupted a lot. That included typical sources of labour firms had become used to tapping, but it also included changes in the patterns of consumption demand (and the derived demand for labour). Add to the story, of course, the surprising pace of the overall economic rebound – spurred by huge fiscal deficits (not just last year when they were needed, but now when they aren’t) – which has led some economists to conclude that the economy and labour market are now operating at very close to full capacity. At full capacity you would hope it wasn’t always easy, or cheap, to find staff (on the other hand, it might be relatively easier for people to find jobs).

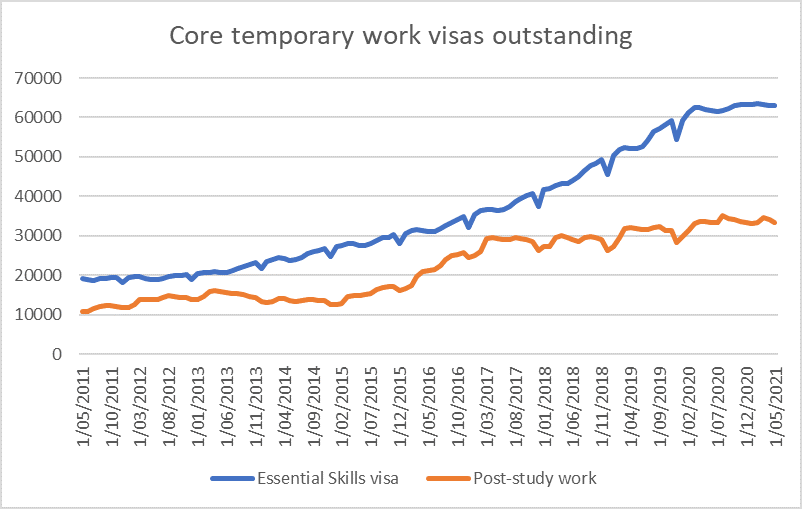

I don’t intend to make this a long post, but before running some quotes from my speech, I thought I’d include a couple of charts with some data that surprised me a bit when I dug it out. The first is the number people here on two of our main short-term work visa programmes – Essential Skills visas (a label that really should be in quote marks, or prefaced by “the so-called”) and Post Study Work visas.

I knew the government had offered visa extensions in many cases, but if you’d asked I’d have guessed that total numbers would have dropped anyway as a reasonable number of people went back home. But, in fact, the numbers here – in these two most skills-focused categories – are almost the same as they were at the start of last year. And numbers on both visas are a lot higher than they were even five or six years ago.

Now, there have been material drops in the numbers here in a couple of other categories (both series quite seasonal).

And those patterns are pretty much what I’d have expected. People have gone home as they’ve finished courses of study, or working holidays, and few/no new people have arrived. But on the working holiday front remember the counterpart – not too many New Zealand young people will have been heading off on their OEs over the last 15 months or so. The types of jobs (here) the two groups might have been looking for may have been a bit different – so some real mismatch issues in some places/roles – but it isn’t as if there are fewer potential workers overall.

As I noted in my speech – bearing in mind the rapid growth in short-term visa numbers in the run-up to Covid.

No doubt some firms have specific difficulties from the sudden dislocation. But there is something wrong with the story when it is seriously claimed – and this is the implication of what so many of these businesses are saying – that a low productivity economy, achieving underwhelming productivity growth, needs more and more immigrant workers each year just to function effectively. Such a story might – just might – have a modicum of plausibility if this was a dynamic fast-growing economy where more and more firms were finding more and more opportunities to successfully compete on a world-stage. But that is nothing like New Zealand’s story.

And, as I’ve noted previously, most OECD countries are not only more productive than New Zealand they are also less reliant on migrant labour. Many business concerns reflect – understandably so – the (sometimes quite legitimate) perspective of a company, but economic policy management is about a country, and the two are quite different.

All that said, one of the points of my speech was to argue that the longer-term immigration settings, around residency approvals, matters far more to economic performance than the rules around limited period work visas. At 45000 residency grants a year, in 22 years the population will be heading for a million more than otherwise (by contrast, at peak there are about 100000 people here on Essential Skills and Post-Study work visas). If you believe in the enabling economic power of immigration, or think that in New Zealand’s case large-scale non-citizen immigration has been quite damaging economically, that is really where one should focus. Open borders people do – in principle, they’d allow (almost) anyone in, to stay. And so do I.

Here is the text from the last couple of pages of my speech on the way ahead

A couple of weeks ago the Minister of Immigration gave a speech foreshadowing changes to policy settings around immigration, apparently with a focus on the limited period visas. There were no specifics, and there was no supporting analysis. There are probably some sensible changes that could be made, but like their predecessors, this government seems all too fond of having officials and ministers decide who should be able to use migrant labour, where and when. I’d rather go in the opposite direction and get officials out of things as much as possible.

I would favour two main changes. First, I would reverse the decision a few years ago to allow students to work while here. If you are here to study, study, don’t compete at the low end of the labour market. And I would get governments out of approved lists, or even salary thresholds, and replace it all with a model in which any employer could hire a person on a temporary work visa but that visa would be

- Subject to a fee, payable to the government (perhaps $20000 per annum or 20 per cent of the employee’s annual income, whichever is greater). That sets a clear and predictable test for whether non-New Zealand recruits are really required, and a genuine incentive on employers to search for and develop New Zealanders (especially for less well-paid positions).

- Subject to a term limit (no individual could be here on one of these visas for more than three years, without at least a one year return home)

But despite the headlines these short-term work visas are still the second order issue. Much more important is whether the government is willing to make any significant changes to the residency programme, or whether business as usual will shortly be resumed.

Neither the government nor the Opposition seen willing to engage on that issue. And if the government deserves a little credit for very belatedly asking the Productivity Commission to report on the New Zealand immigration model, strangely they seem to be proposing to make policy before the Commission reports.

What should they be doing?

First, we need to explicitly recognise that the residency programme (the driver of medium-term policy-led population growth) itself comprises several different types of people.

It includes people we are never going to restrict. If your daughter does an OE in London and finds a British man to marry, he’ll be entitled to move here permanently. No one would want to restrict those numbers, and there is no quantitative limit.

It includes those we take in as refugees. There is no economic motive for the refugee quota, it is all about humanitarianism.

But the bulk of the programme is purely discretionary. And the numbers involved have borne no relationship to the rather limited (highly productive) economic opportunities here.

There are all sorts of myths about migrants to New Zealand. By international standards the skill levels mostly aren’t too bad – being a distant island means you really only get in legally, and it is an economics (rather than family) driven programme. But the skill levels aren’t spectacular. And why would they be? Much as New Zealand is a pleasant enough, and peaceful, place to live it is (a) remote, and (b) now not very prosperous, and (c) small. The smartest and most ambitious and most driven of the potential migrants are much more likely to go to other migration-welcoming countries if they can get in. A country whose own people leave en masse isn’t a great advert for abundant economic opportunities.

And we aren’t even ruthless about demanding highly-skilled people. We run specific programmes for people from Pacific countries who don’t have the skills/education to qualify as skilled migrants. And we give extra points to people who are willing to live outside the main centres, even though the main centres are where most of the economic opportunities and higher paying jobs are. We structure the system to subsidise NZ universities, by favouring applicants with NZ degrees and work experience even though NZ universities are nowhere near best in the world, and NZ’s economy is a low productivity beast. And so on. There is talk from time to time about attracting the best tech people, but why would they come here – small, remote, not very wealthy, no great universities, no relevant centres of expertise or funding, and so on?

And so we bring in lots of pretty-average people, adding nothing systematically to NZers’ prospects There is nothing wrong with being “pretty average” – that’s most people – but it isn’t going to do anything to transform our productivity performance. Hasn’t so far, and no reason to suppose it will any decade soon.

New Zealand’s economy could do such much better. But all the signs are that it probably can’t match the best with a population that is growing rapidly – much more rapidly than the productivity frontier countries. Distance hasn’t been defeated and if anything may have become more important. There is lots of wishful thinking around the New Zealand debate, but any serious confrontation with the stylised facts of New Zealand’s experience, augmented with the experience of other former settler societies, is that large-scale immigration just hasn’t helped for a long time. You might think the US is an exception, but it isn’t really. It was – like us – one of the handful of richest countries in the world 100 years ago, and despite having had much more rapid population growth than European countries (and no ravages of war or communism) the gaps have narrowed. Denmark is probably the standout performer today.

If political parties were serious about reversing the decades of relative productivity decline – and there is no sign of it – there is a variety of things mutually reinforcing things that should be done, which together would prompt much more business investment and a more outward-oriented economy:

- We should take a much more open approach to foreign investment – I’d remove all controls in respect of investors from OECD countries.

- We should be lowering the tax rate on business investment – our company tax rate (which matters a lot for foreign investors) is in the upper part of the OECD range, and what you tax you get less of.

- We need to free up land use, within our cities and across the country.

One could list other things (GE issues for example).

But most importantly, we need to end the delusion – for that is what it is – that a very remote country, which lots of its own people leave, which has fallen steadily behind an increasing number of other countries, and where foreign trade is shrinking as a share of GDP, is a sensible place for government policy to promote large scale immigration. It wouldn’t make sense for Taihape; it doesn’t make sense for New Zealand. Immigration policy is one of the largest structural policy interventions in our economy. And now – before we reopen the borders – is the time to act.

So let’s not go back to granting huge numbers of residency permits. Cut out the Pacific quotas – no reason to favour people from those countries any more than those from (say) Britain and Ireland (that we once favoured), and cut back the total approvals to, say, 5000 to 10000 really highly-skilled people (if we can find them) with no preferences given to NZ qualifications and experience, simply looking for the best and most energetic. Add in refugees and the spouses/partners of New Zealanders, and you’d be looking at an overall number of residency approvals each year of 10000 to 15000. In per capita terms that would be a similar rate to the US.

Successful countries make their economic success primarily with and for their own people. We can again do it here. We have talented and fairly well-educated people, we have reasonably open markets, we have a history of innovation, but distance really works against us and we will mostly prosper by doing better and smarter with (and investing more heavily in) the natural resources we have – things that really are location-specific. Lots of other bright ideas are, and will be, dreamed up by people here. But if those ideas work well, they’ll typically be much more valuable abroad. You may not like it – neither do I really – but it is what experience shows. We’d be foolish to simply start up the same old model and expect better results in future.

despite being a temporary visa holder, I applaud you for an intelligently written post. your policy prescriptions will probably be ignored by the major political parties, but they make sense. kudos.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you Michael. My first post. While I disagree with many of your blogs, you are spot-on with this issue. NZ has not been well served by large-scale immigration. It has not increased our productivity, nor our per-capita wealth or income. It has put tremendous pressure on the housing market and on our broader infrastructure: water, sewerage, roading, health, education to name just a few. It has sidelined a generation who struggle to live here with dignity.

Immigration has congested our cities, all of which were poorly designed with little thought given to scale expansion. City assets are now typically delapidated and over burdened. Just look around Wellington or Hamilton.

Immigration has become entrenched as the only way of filling low skiiled jobs.

Politicians and others seem to extol the purported virtues of immigration, almost without exception. Evidence is not required on this issue! Not to repeat the immigration mantra is wrongly labelled racist or xenophobic, but the issues above are simply about population growth in excess of what a poor pacific backwater like NZ can handle. And so, as Covid recedes, more immigration will be on the cards – you can hear the talk already. Housing and infrastructure pressures will get worse, not better.

If the OECD had any integrity, it would immediately rescind NZ’s membership so that we could all acknowledge that NZ is no longer a developed country. We were once, but failed to keep up the maintenance. Sad but true.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. The OECD goes in the other direction and keeps letting in middle income countries who have the incidental effect of making NZ look a bit less bad on oecd rankings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Too many places where I completely agree with you. But it is fun disagreeing with an economist about arithmetic.

You are aiming for permanent residency approvals of 10,000 to 15,000 per year while having 5,000 to 10,000 skilled migrants. Taking your lower figure of 5,000 for skilled migrants and assuming it includes their partners and children then add these figures for 2017: 3,900 in the International/Humanitarian criteria, 9,442 partners with another 3,458 in the Parent/Sibling/Adult Child stream. You are over 17,000 before you start. Since 2017 NZ has increased its refugee quota.

Next piece of arithmetic: “”At 45,000 residency grants a year, in 22 years the population will be heading for a million more than otherwise””. Well that is 990,000 which heads to a million but you have forgotten the strong preference for new skilled residents to start families. Our two grandchildren attending up-market pre-schools in Auckland are in ethnically diverse classes; even the rare kids of Caucasian appearance have adults picking them up speaking in foreign tongues. Of course these kids are Kiwis by birth just like my Melanesian grandchildren but without the INZ’s approval of their parent’s permanent residency they would not be in NZ. I can only guess but I’d suggest NZ population growth over 22 years averaging 45,000 annual residency grants would be nearer two million.

It matters little if you or I have our numbers correct because either way it is certain that Auckland council will be astonished that they need more teachers, classrooms, roads, hospitals and doctors.

Thank heavens for emigration. Our government depends on it.

LikeLike

Hi Bob

On your first point, the skilled migration numbers incl current partners and children of the principal applicants. As we’ve discussed previously if the flow of principal applicants was dramatically slowed so too would the subsequent flow of later partners (many related to single male Indian migrants).

On your second point you are of course right about children but there is also the fact that some of the 45000 don’t stay long term. I could probably have phrased the sentence more accurately but I didn’t have words to spare (the text as it stands was fairly ruthlessly pruned to get to my time limit).

LikeLike

You simply cannot get pass the fact that old people are not dying. The longer they live the more health problems, with the need for hospitals, nursing homes, rest homes, drivers for Daisy vehicles to and from hospitals, recreation.

It takes 3 hours of a carer/helper for each meal to care for a dementia patient. That is already 1 young carer/helper for each dementia patient. You can dream on of fewer migrants and so does this impractical Jacinda Ardern government but increasingly the government will crack under the glaring headlines of “Senior person dies frozen on the toilet”.

LikeLike

We aren’t going to agree on the implications for appropriate rates of immigration, but eminent economist Charles Goodhart does argue that the point about the incidence of dementia etc is one reason why the world should expect much higher inflation and higher real interest rates in the next couple of decades.

LikeLike

I arrived as a ‘skilled’ immigrant in 2003 and have brought with me a partner (more skilled than myself) and her four children all of whom are now adult. Now I have three grandchildren. So one skilled immigrant arriving in 2003 has resulted in nine inhabitants – we own six cars congesting Auckland roads, have required various medical procedures, occupy four houses. We are all happy to be in NZ. My point is how hard it is to quantify the effect of each immigrant both in what they produce and what they consume.

I don’t have the figures I used to collect at hand but I remember being surprised as to how fairly evenly split the male/female figures were for principal applicants across all the main countries. Of course female graduates also may choose to go to India, China or the Philippines when looking for a partner. Maybe it is not an issue relating to male or India but to student.

LikeLike

Yes I agree that the full demographic impact is hard to calculate, but bear in mind that if a couple with two kids migrate and those kids have 1.7 kids between them ( the NZ TFR) the multiplier from migrants to total population increase over time is a lot less than in your own example.

Also worth noting that you point also holds to some extent for the outflow of NZers to Aus over the years (the total population implications are prob larger than than the headline numbers suggest).

LikeLike

https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/industries/123541263/nzs-welcomed-a-lot-of-nice-people-few-trailblazers-through-immigration-nzier

“”A report on migration from the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER) for the Productivity Commission concludes that the country’s high level of immigration has not resulted in improved productivity or a significant boost to gross domestic product (GDP).””

As Ms Julie Fry says “”New Zealand has welcomed large numbers of perfectly nice immigrants … having very modest impacts on GDP per capita””

LikeLike

Personal Experience

Back when the use of computers was exploding, my Wife and I established a key-punch data-entry bureau. Started with 5 employees, growing to employing 20 girls. In the early stages as we grew, adding an extra employee was always positive. Total productivity of the entire team went up, output of as it added to the companionship and harmony of the team. Then, suddenly, adding an extra 2 or 3 employees, the productivity of the whole operation nose-dived. Harmony among the staff reduced. We had to cut back on staff, because we had reached the level of numbers at which the marginal benefits dis-appeared.

For a number f reasons, I believe the same has happened with immigration. If there was a marginal benefit in increased immigration we would not see the downward pressure on wages and exploitation of employees having to pay $20,000 to be bonded to a liquor supplier, or working 80 hours a week and getting paid for 40 hours

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think you have left out the part where a key punch data entry businesses would have reached peak sales as the business model became obsolete and adding staff to try and boost a dying business was just desperate management judgement? Nothing really to do with more staff just desperate owners.

LikeLike

1) Population Strategy (to set Immigration rate to assist achieving target):

Target: Let overall NZ Inc Target = maximise gdp/capita growth – cost of externalities = wellbeing per capita growth of NZer’s and wellbeing of its environment.

2) Then set immigration rate

There needs to be a clearhouse determined by price for the immigration rate in 1)

Employers to bid for visas. They can then decide whether or not to import labour or train NZer’s.

3) Productivity

Most of NZ is small businesses. There are no economies of scale & few grow to large businesses.

The only big sector is farming which is maxed out & faces significant further growth issues due to water pollution, GHG emissions & in the long term synthetic proteins

Of the top 20 NZ companies (https://www.interest.co.nz/nzx50) only 3 make anything for export – Fisher&Paykel Healthcare, Ebos & A2 Milk, the rest simply service the domestic economy.

FDI may be the only way any large companies with an export focus and productive economies of scale can be established.

4) But should we be concerned with productivity only?

I say no. We can have a very productive economy by stripping out all human and environmental regulation. (seems we were still doing this illegally – https://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/AK2106/S00240/high-court-victory-for-tarakihi-recovery.htm)

The issue is we are only looking at GDP when considering productivity.

We need to look more broadly and be looking at, as above, gdp/capita growth – cost of externalities, i.e. wellbeing per capita growth + the wellbeing of NZ’s environment.

LikeLike

With only 1% urban use for our tiny 5 million people with land mass above water the size of Japan and the underestimated under water land mass the size of Australia, NZ access to natural and mineral potential resources is unsurpassed. Our population could easily be the richest people on the planet. We just refuse to exploit any of that vast resource. Only a wealthy country like NZ can decide to be poor by choice.

LikeLike

40% of Auckland is being powered imported low grade highly polluting Indonesian coal. NZ has High grade low polluting coal but cannot be mined due to draconian environmental and health and safety laws. NZ has one of the largest territorial waters in the world but has banned offshore oil and gas or any mining of its vast oceans.

LikeLike

Thanks for posting the link to the presentation. I think one of the most compelling parts was the narrative around the top of p8 – New Zealand is a nice enough place but it isn’t amazing economically, socially or culturally. It isn’t ‘world leading’ or ‘innovative’ despite what all the fluff you read from Ministers of various stripes in speeches written by MBIE or other Departmental officials. People continually saying so makes a rod for our backs as it starts the debate on economic performance from a position which is fundamentally incorrect. MBIE or whoever writing more speeches about how great NZ is will not magically make it the case and I think until there is a realisation on that point by officials and (largely captive) Ministers the debate and path to finding solutions to increase performance or productivity or whatever one wants to call it isn’t even in first, let alone top gear – people are just kidding themselves.

As an example, I remember at Treasury a senior person there boasting about how they had been to some big conference and lectured the Norwegian delegate about how good New Zealand was at something (budgeting or something equally dull), and how rubbish Norway was at it comparatively, and how we were world leading blah blah, nothing to learn from them. Norway is the wealthiest country on the planet pretty much. Would they trade their economic performance for ours if it meant their budget had the words ‘well-being’ on it and it had some ‘frameworks’ in it? Somehow I think not.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Norway is one of the richest countries in the world due to the fossil fuels it has extracted.

For a wider take on wellbeing see:

LikeLike

Re immigration:

Many NZ businesses have set themselves up to fail by outgrowing their staffing capabilities.

This extract from an article in todays Southland Times:

“The owner of five Southland dairy farms says the staffing shortage hitting the industry is a safety and environmental disaster waiting to happen.For the past two months his HR staffer has been trying to fill three 2IC roles on his farms, but without luck.

Abe de Wolde owns five Heddon Bush farms which milk 4500 cows and hires between 30 and 35 staff, depending on the season.

Of his 30-odd staff on farm, just two were New Zealanders.

“New Zealanders just don’t want to work on dairy farms,” he said.

“We employ nine different nationalities, India, Nepal, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Ireland, Brazil, South Africa, Holland [and New Zealand].””

Note the owner himself is an immigrant….

A consequence of corporatisation of farming, horticulture etc

LikeLiked by 1 person

NZ exports 95% of its primary production. We are the largest exporter of milk in the world. UK farmers do not want us in their market and will protest our FTA with the UK. Europe will never give us an FTA now that UK has Brexited. It is not that we are more efficient producers, It is very simply that the NZD is discounted by 50% to the British pound and discounted by 40% to the Euro. We are in the category of corporatised and highly organised product dumping.

LikeLike

The Synlait Youtuber Lee Williams was fired by Synlait and Westpac won’t have him as a customer (I think that is general not just his go fund me account). He is rough around the edges and they probably got him on aesthetics more than anything, but the charge was parodying the Maori Party. I suppose the lesson is that while you might think an MP in Viking garb blowing a horn is ridiculous you have to take it at face value as “their culture” and not judge?

But shouldn’t banks and other utilities be protected from activist pressure? It is looking like a person here being non-personed. Note how RNZ gave Ngai tahu researchers a free pass on their 7th century Antarctic explorations? How squeaky clean is Westpac?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Michael: “the overall economic rebound – spurred by huge fiscal deficits”

An interesting (and seldom discussed) question arises: what is the real economic growth rate absent unsustainable debt fueled consumption. GDP increase minus the increase in debt? You would have to separate out genuine investment in infrastructure and the like – “investment” in benefit increases not so much. I guess, at present, it would be deeply negative.

Any thoughts Michael?

LikeLike

Debt is only unsustainable if the RBNZ forces interest rates to a level that undermines the profitability of the businesses creating jobs.

LikeLike

Don’t forget that interest rates are a cost to businesses. The higher the interest cost, businesses have to increase prices to maintain profit. Therefore higher interest rates forces up inflation in a growing economy. The only time that higher interest rates dampen inflation is when interest rates reach a High enough level so that businesses start to shut down and employees are made redundant.

LikeLike

Thanks GGS but not particularly helpful.

Perhaps I should have said “increasing debt at unsustainable rates”. In any case business borrowing (and investment) is trending significantly downward, that is a concern but what interests me is quantifying the boost to GDP from increasing government borrowing and spending; what would the GDP figures look like minus that spending.

Say GDP was up 20 billion but the government injected 50 billion, do we keep pretending we have a healthy, growing economy? What happens when they stop? What happens when lenders and investors see our “thriving” economy is built on sand, a delusion? Will our currency crash and interest rates soar as a consequence? What can the RBNZ do in such a scenario?

LikeLike

There isn’t really a meaningful way to answer that David. Without the big fiscal deficits now, monetary policy would be set looser (OCR lower) than it now is (that is how mon pol works). Most likely the overall level of GDP would not be much different, but public debt (actual and prospective) would be quite a bit lower. Private debt might be higher in some cases – again that is how mon pol works – but the people who had taken on the added debt would have done so more voluntarily than the additional public debt the govt assumed for us all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Michael.

LikeLike

[…] https://croakingcassandra.com/2021/06/18/immigration-policy-for-new-zealand-post-covid/ […]

LikeLike