As most New Zealand readers will now know, TVNZ’s Q&A programme yesterday featured a debate around the economics of immigration. Unfortunately, the programme got prominence not for anything of substance that was said by the participants, but for a vulgar outburst by Shamubeel Eaqub. It was pretty unfortunate, but then this was the guy who only a few weeks ago was dismissing my analytical arguments as “that’s racist” , and then turned his attention to Fonterra, suggesting they were treating their investors as ‘scum’.

TVNZ got together Don Brash, Shamubeel Eaqub, and Massey University population/immigration professor, Paul Spoonley. They had asked me to go on the programme, but I don’t do work-like things on Sundays.

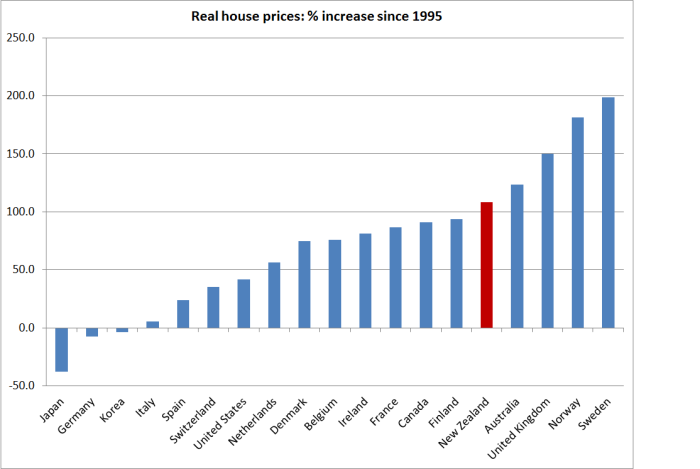

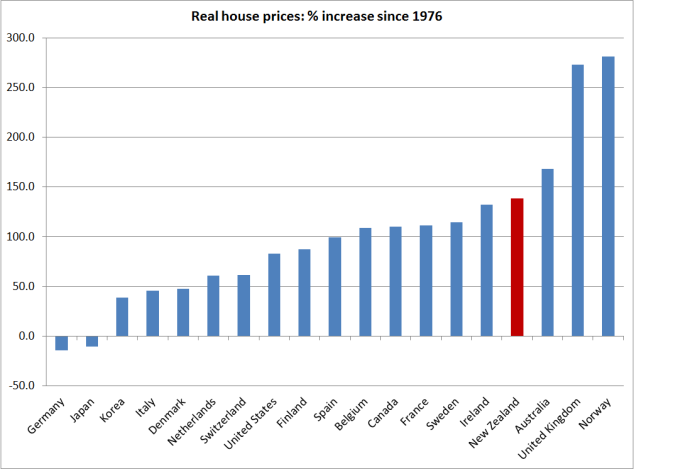

Don Brash articulated some of my macroeconomic arguments about the impact of our large-scale programme of targeting non-citizen migrants. I’ve argued that in an economy with modest savings, high average immigration inflows exacerbate pressures on real interest rates and the real exchange rate. We’ve had the highest real interest rates in the advanced world for several decades, and a real exchange rate that has been much higher than is consistent with our dismal productivity performance. In combination, the high real interest and exchange rates have squeezed out business investment – our levels have been low for decades – and skewed returns in ways that favour investment in the domestic or non-tradables sectors. Returns from investing heavily to tap world markets just haven’t been there, so even once we opened up our economy, business investment in the tradables sector has been subdued. None of this is a story about the last 12 months, or any short-term window, it is about average patterns seen over the last 25 years or so. (Unfortunately, some of the debate got bogged down in the last 12 months’ data.)

One should always try to ensure that one understands the arguments people on the other side are making, so in this post I have tried to identify the various points that Eaqub and Spoonley were making, and offer some comments on them.

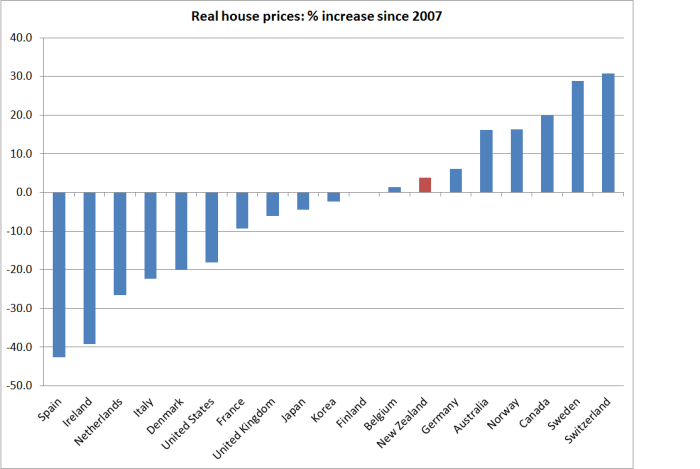

Eaqub started out by simply asserting that my arguments were wrong. He argues that volatility of net immigration is an important issue (“the short-term pressures are absolutely clear”) especially in the context of house prices. He argues that we need to “fix” housing supply responsiveness and associated infrastructure issues. He goes on to claim there is just a failure of political leadership, and that any “infrastructure” issues could be dealt with by more government borrowing, since the government faces no debt constraint.

Of course, I agree that housing supply responsiveness should be improved, and that the central and local government policies that impede these are a scandal. But he seems to totally miss the point of my argument. Real resources that are used for building houses or “infrastructure” can’t be used for other stuff, and the real exchange rate and the real interest rate move to free up resources to meet these population-based demands. We could have more investment in, eg, Auckland roads, but all else equal that would put more pressure on scarce resources. Meeting the demands of a rapidly rising population squeezes out other stuff – in this case, business investment, especially that in our tradables sector.

Eaqub also asserted at this point that “immigrants are good for New Zealand, as they been for centuries for New Zealand. They’ve increased our human and physical capital base”.

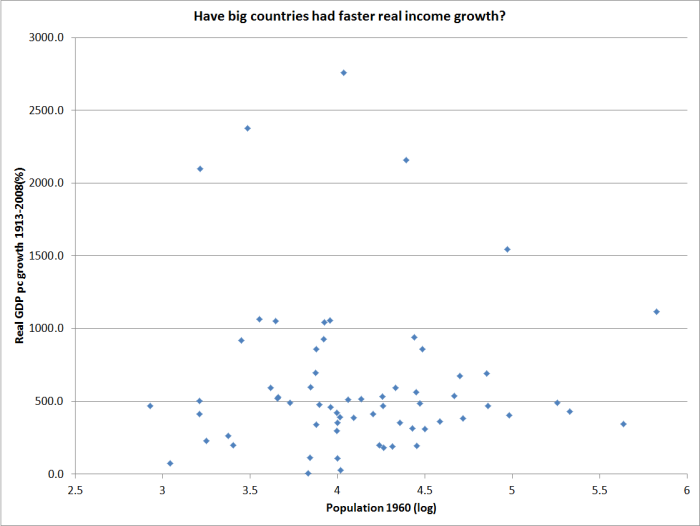

Don Brash challenged him as to whether the increase in the total size of the economy from the large scale immigration programme had had benefits for New Zealanders, noting that productivity growth in New Zealand had been weak for decades. He articulated a story in which the far-reaching reforms of the late 1980s and early 1990s had not reversed that underperformance, even though immigration policy had been materially liberalised at much the same time.

Eaqub responded to this by arguing that “perhaps they weren’t the right reforms”. That is a reasonable possibility to explore, but he didn’t back it up. He said that deregulating the economy had been “fantastic”, and the only policy he cited that he was uncomfortable with was the amount of student debt being “piled on” students. Reasonable people might have a range of different views on that one, but given the surge in New Zealand tertiary participation over the last 25 years, it is difficult to know what mechanism Eaqub had in mind for how student loans policy might explain much of New Zealand’s economic underperformance.

Eaqub also repeated the argument he made in his recent book that net immigration has not accounted for much of total population growth in the last 50 years. But as I’ve pointed out previously, net migration includes the coming and goings (mostly the latter) of New Zealanders, and that a discussion about immigration policy needed to focus on the flows of non-citizens (the bit the New Zealand government controls). As I’ve explained previously, and as Don highlighted, without non-citizen immigration, our trend population would now be flat or falling. There would be cyclical population pressures on the housing market, but no trend ones.

The interviewer drew attention to the 2006 Australian Productivity Commission study Don Brash has cited which concludes that any gains from immigration were captured by the migrants, and there was no gain to Australians. Don noted that there was no comparable study in New Zealand and that there is little or no evidence that New Zealand’s immigration programme has improved productivity or economic well-being for New Zealanders.

Eaqub rejected that proposition, advancing as evidence a recent NZIER piece. That seemed rash. The NZIER piece in question is a four page note, and its conclusion were based on a single unreported equation (the Australian Productivity Commission report was, by contrast, hundreds of page long). I went to a discussion on the NZIER paper at Treasury last year, and I think it would be fair to say that even the advocates of immigration who were at that meeting did not find it particularly persuasive. And, in any case, since the single equation looks only at total (per capita) GDP, which combines GDP accruing to New Zealanders and to immigrants, it does not shed light on the specific question at hand: if there are gains from immigration, how many (if any) of them have flowed to New Zealanders as distinct from migrants. Notwithstanding his claims for this NZIER note, Eaqub actually went on to acknowledge that the bulk of gains from immigration flow to the migrants, before asserting that it is “absolutely clear” that the type of immigration policy we have in New Zealand is improving skills and human capital. As Don noted, actually many of the migrants (temporary and permanent) don’t seem that skilled at all.

The interviewer interjected my past references to work done at the Reserve Bank suggesting that a 1 per cent of population immigration shock had boosted house prices by perhaps 7 or 10 per cent. Eaqub came back with his assertion again that the only thing that mattered was the volatility in net migration, reiterating this claim that net migration can’t explain most of growth in population, while ignoring the distinction between immigration of non-citizens (the bit the New Zealand government controls) and other flows. (Somewhat surprisingly, later in the show Eaqub actually claimed that New Zealand had relied on immigration for its population growth throughout its history)

In the second half of the show, the interviewer introduced some of the numbers I’ve run here about the number of shelf-fillers and checkout operators who had been given work visas under the Essential Skills category. He went on to suggest that “beggars can’t be choosers” and that perhaps the best people just wouldn’t want to come to New Zealand. Somewhat surprisingly, Eaqub rejected that suggestion (I’ve previously heard it acknowledged by leading academic advocates of immigration) asserting that we “generally” get “very highly skilled people”, [even though no more than half of the permanent residence approvals are even in the skilled/business category, which includes not just the primary applicant but their immediate family] before rushing on to the “massive shortages” in places like orchards. Eaqub argued that the challenge is to boost human capital, and that we need “more skills” to compete in the global economy. Despite our very large inward migration programme, he made no effort to show how this has actually been happening – in, for example, an economy where the share of exports in GDP is unchanged over 30 years, and where productivity growth has been among the worst in the advanced world. Paul Spoonley backed up Eaqub claiming that, while not defending the checkout operator approvals, “by and large we are bringing in the right people” and that we had a selection system that was the envy of the world. He has just returned from Europe, where people would “die” for our system. But here I should add that one of the advantages New Zealand has is that we have near-absolute control on who comes in – we don’t have boat people, or other illegal migrants, and only Australians have automatic rights to come here (and not many do). The question is whether there is evidence that the migrants we’ve had have added to the economic well-being of New Zealanders.

Discussion turned to the (quite large) family reunification component of our immigration programme (around a quarter of approvals). As Don Brash noted, many of these people don’t appear to be particularly highly-skilled migrants. Eaqub’s somewhat surprising response was along the lines of “there has to be a human element to it. You can’t just allow people in and then say they can’t maintain family connections, and we need empathy in policymaking”. But……immigration policy is supposed to set to benefit New Zealanders (that “economic lever” MBIE and ministers tell us about). No migrant is forced to come to New Zealand, and any are free to take holidays back home (or to have family holiday here). And unlike the 19th century, technology now enables people to talk to overseas family easily and cheaply as frequently as they like.

Eaqub went on to argue that there was no problem because immigrants as a whole provided a fiscal boost to New Zealand public finances. That is by no means certain, but even if we accept that the average migrant does makes a positive fiscal contribution, that need not be true of the marginal migrants, and as economists and policymakers we should be thinking at the margin. Many migrants probably make a positive fiscal contribution. But those who come under family reunification approvals in mid-life almost certainly do not (they typically don’t pay enough taxes for long enough to cover the full NZS and health entitlements). It was at about this point that his vulgarity occurred – the expletive perhaps being a substitute for a missing substantive argument?

Paul Spoonley offered a slightly more sophisticated defence, arguing that our family reunification policies help provide migrants with a reason to stay in New Zealand (the centre of the family is now here), and that the cheap childcare the grandparents could provide was an economic gain for New Zealand. His attachment story is a plausible argument, although whether it stands up to empirical scrutiny is another question. Perhaps instead primary migrants stay just long enough to get families into New Zealand and secure health and welfare rights? Having “bought the insurance” and secured the family, there is no compelling need for the migrant to stay. But even if Spoonley is correct, it simply puts more of a burden of proof on the advocates of immigration – if we need to bring in family members and parents, and provided associated welfare support, to get migrants to stay, we should be very sure that the primary migrants themselves are substantially benefiting New Zealanders by being here. There is little real evidence of that so far.

The interviewer also raised the question of our ability to attract high net worth investor migrants. Don Brash noted that it wasn’t matter of how many we attracted, or how much money they might bring, but of whether any inflow (of financial or human capital) boosted productivity for New Zealanders. For that, he asserted, the evidence was skimpy. Eaqub reiterated his claim that in fact the evidence is yes, that gains accrue over long periods of time, and that we have relied on immigration for population and productivity growth across all our history. In his view, it made no sense to arbitrarily look at the previous 25 years or so. This made little sense to me. First, as Don Brash pointed out our productivity growth (relative to other countries) has been atrocious for decades. And second, we actually had a major change of immigration policy 25 or so years ago, and a conventional approach to policy evaluation would suggest looking at what had happened in the economy in the subsequent years.

Eaqub was asked by the interviewer what level of immigration he would regard as too high. He argued that we need to focus on medium-term trends, not annual fluctuations. This seemed inconsistent with his story that the volatility of net migration was the only problem, but perhaps it wasn’t. He seemed to favour bringing in any number of “high quality and skilled people”, and that the only problem is other “broken markets” (presumably housing supply and immigration.

In concluding the discussion, neither Don Brash nor Shamubeel Eaqub seemed keen on the recent change to immigration policy that will give more points to those willing to settle somewhere other than Auckland. As I noted recently this will, more or less as a matter of algebra, lower the average quality of the “skilled” migrants we do get.

Spoonley didn’t weigh in much on the bigger economic issues. He thinks we choose migrants well – even though seriously high-skilled migrants make up only a moderate share of our overall immigration programme. But as Spoonley noted in his 2012 book “understanding exactly how immigrants contribute to economic outcomes is still somewhat fraught in the New Zealand context”.

Eaqub made most of the economic arguments in defence of New Zealand’s immigration programme, but in the end I was a little surprised at how thin his case seemed to be. Despite his comments:

- We simply have nothing comparable in New Zealand to the Australian Productivity Commissions studies on the economic impact of immigration.

- Housing market problems certainly could be fixed without touching immigration settings, but there is no doubt that policy-controlled immigration (the inflow of non-citizens) is now the only source of trend population pressure on the housing market. And annual fluctuations simply aren’t that controllable.

- A surprisingly large proportion of New Zealand permanent residence approvals are not coming in under the skilled or business stream, despite the official rhetoric about a skills-focused immigration programme. Even among those who are, many are dependents, not those who have independently demonstrated value to New Zealand, and a disconcertingly large share of the “skilled” migrants don’t seem that skilled at all

- Despite the repeated mantra about the need for more skills and more human capital, there is no evidence I’ve seen that New Zealand is now particularly short of human capital, or that large scale migration can easily resolve the gaps there might be. We now have high levels of tertiary participation, and rather low estimated economic returns to tertiary education, suggesting that availability of “skills” isn’t the pressing constraint on lifting New Zealand’s medium-term productivity performance.

- We need to be thinking about immigration (like all policies) at the margin, not as an average. I’ve no doubt that there are some migrants who make a huge contribution to New Zealand, and to New Zealanders. But I think there are some pretty good arguments that the 45000th permanent residence approval is unlikely to be generating a net gain at all. If there really are material gains to be had from immigration, we could presumably capture most of them with, say, an annual target of 20000 permanent residence approvals, especially if we wind-back further the family categories and focus on genuinely high-skilled migrants.

There may be other good explanations for the stylised facts around New Zealand:

- Persistently high real interest rates

- A persistently high average real exchange rate

- Persistently weak productivity performance, despite much-lauded liberalisation in the 1980s and early 1990s

- Persistently weak business investment,

- A persistently modest export sector

- A persistently high level of net international debt, despite the strong government balance sheet.

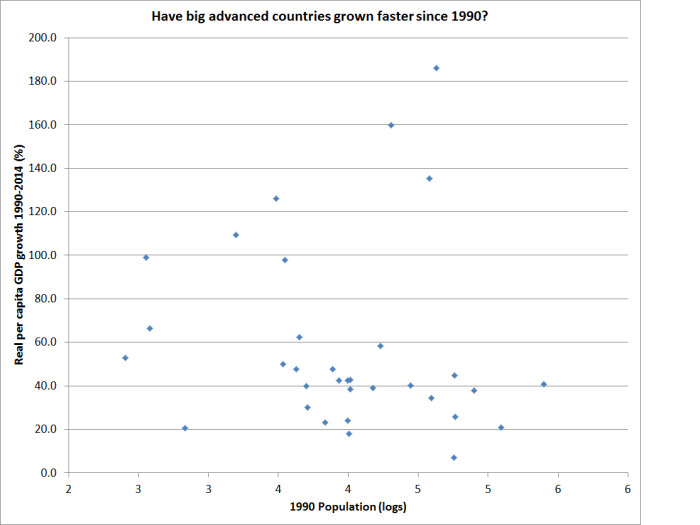

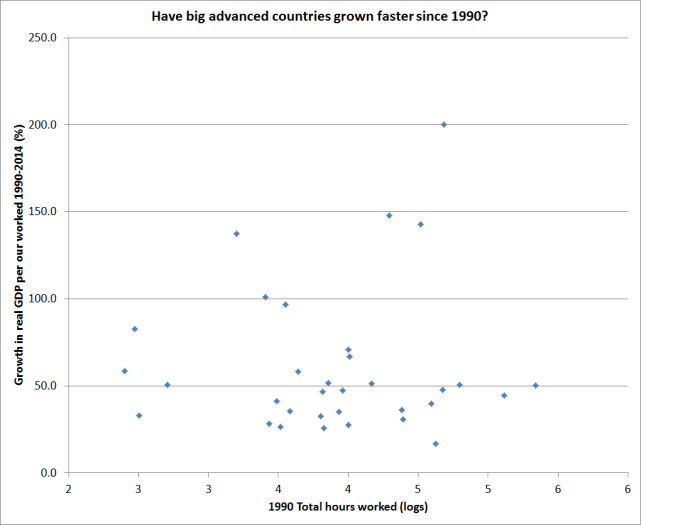

But against that backdrop, the very large scale non-citizen programme that New Zealand has run over the last 25 years – a really big policy experiment – looks a plausible candidate for what might have gone wrong. At best, the advocates of the large experiment are still struggling to show that there have been any real benefits for New Zealanders. At worst, if my story is right, much of the expansion in total GDP that we have had in the last 25 years might have been at the expense of the sort of productivity gains that would benefit all New Zealanders. Since 1990, not many advanced countries have had more growth in total real GDP than New Zealand, and not many have had less growth in real GDP per hour worked.

There is apparently a great deal of faith among New Zealand elites that our large-scale immigration programme is “a good thing”. As I’ve noted previously, in the biblical book of Hebrews, there is a verse that reads “Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen”. The evidence of the economic benefits to New Zealanders from one of the largest controlled immigration programmes anywhere still remains largely a thing not seen,