I’ve been looking at how advanced economies have performed since 2007. New Zealand has not done that well, contrary to some of the stories one sees around (eg the somewhat incredible “rockstar economy” phraseology that held sway for a while).

It surprised me that New Zealand had not done a little better since 2007. As I noted last week, we have had some of the strongest terms of trade of any OECD country. But we also had other advantages. For example, we did not have a substantial domestic financial crisis. No major financial institution failed, and although many finance companies failed they were fairly peripheral. Overall loan losses appear to have been relatively modest, and any disruption to the financial intermediation process – of the sort often discussed in the literature around the economic costs of financial crises – must have been slight at best. That New Zealand and the United States have had such similar paths of GDP in the last decade has left more sceptical than I was of the proposition that financial crises have large sustained real economic costs.

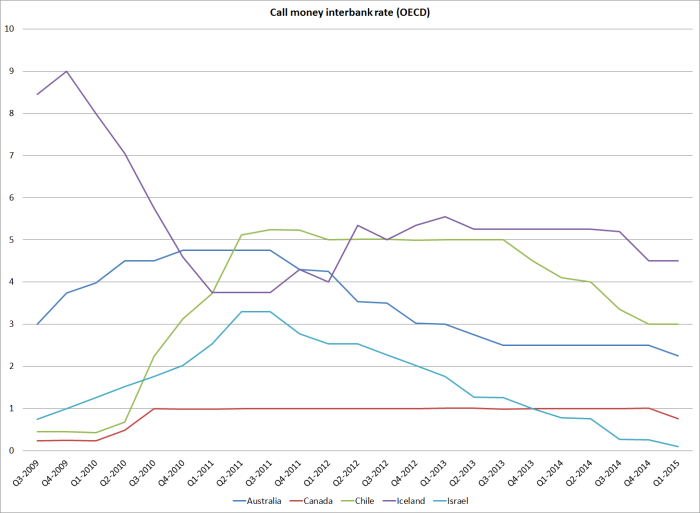

New Zealand also had more macroeconomic policy leeway than most countries. Macroeconomic policy tools – fiscal and monetary policy – don’t make much difference to a country’s long-term prosperity, but they can make quite a difference to a country’s ability to rebound quickly from shocks. Thus, for example, almost half the advanced countries I’ve been looking at are now members of the euro area. Individual countries have no national monetary policy (so they can’t adjust their own interest rates or their nominal exchange rates) and the region as a whole has been at or near the lower bound on nominal interest rates for years now. Many other advanced economies – the US, UK, Japan, Switzerland, Sweden, the Czech Republic – are also at the lower bound for nominal interest rate. In all cases except Japan, they were able to cut policy rates a long way when the recession hit, but then they ran into limits.

New Zealand did not run into such limits. In 2008/09 the Reserve Bank cut its policy rate, the OCR, by more than almost any of the other advanced country central banks. But even then the rate was still 2.5 per cent. There was plenty more leeway had that been judged warranted. And during the recession itself, our floating exchange rate fell very substantially..

But the other area of macroeconomic policy where we had leeway was fiscal policy. Intense debates rage around the role of fiscal policy in economic cycles. When a country is not at the zero bound it seems reasonable that the stance of fiscal policy won’t make much difference to the path of GDP (although it may affect the composition, and in particular that between tradables and non-tradables). But it is likely to be a different matter for a country at the zero bound. If there is little or no effective monetary policy leeway, changes in the fiscal balances are likely to have reasonably predictable “Keynesian” type effects: fiscal contractions will dampen recoveries, and fiscal expansions will support them. Of course, confidence effects can undermine those effects, but in reasonably well-governed countries with floating exchange rates, it takes a lot to lead to material adverse confidence effects. There is no evidence, for example, that the UK or the US came close to triggering serious adverse confidence effects during the years since 2007.

Turning to the IMF WEO database again, we can see what has happened to (estimates of) structural fiscal balances since 2007. I would stress the word “estimates” – no one can ever know the level of a structural fiscal balance with certainty, and current estimates for 2014 will be revised, in some cases perhaps quite substantially. But here is how structural fiscal balances have changed since 2007.

Around half the countries have had fiscal contractions over that full period, while the other half have had expansionary fiscal stances. Over the period as a whole, only seven countries are estimated to have had more expansionary fiscal stances than New Zealand. What I found interesting is that of the 15 countries to the left of the chart, 10 had floating (or flexible in Singapore’s case) exchange rates. Of the countries that have had contractionary fiscal stances, only a handful have flexible exchange rates.

Like most countries, New Zealand’s picture is one of two halves. There was a huge shift from substantial structural surpluses as recently as 2007 ( when only Singapore had a materially larger structural surplus than New Zealand) , to large structural deficits just a couple of years later. When I did one of these charts back in 2010, New Zealand had then had (depending on the measure used) either the largest or second largest expansionary shift in fiscal policy of any advanced economy. The odd thing about New Zealand’s shift was that almost none of it was fiscal stimulus measures initiated once the recession hit – it was all the effects of decisions made when it was thought (by politicians and their Treasury advisers) that times would stay good.

Since 2009 New Zealand, like many other countries, has been gradually reducing its structural fiscal deficit. My point here is simply that we had the flexibility to do so, fast or slow, without materially affecting the economic cycle, because we never ran out of room to use conventional monetary policy to offset the short-term demand effects of fiscal consolidation decisions. Having, on average, the highest real interest rates in the advanced world isn’t a good thing for our longer-term growth prospects (I argue) but in getting through the last few years it has had one distinct upside – we had more room to cut rates than almost anyone else. Given our disappointing economic performance, and weak inflation outcomes, one might argue that it is a shame that that leeway was not used more aggressively.

And finally, a chart of the IMF’s estimate of the level of each country’s structural fiscal balance in 2014. New Zealand looks pretty good on this score (although the terms of trade flatter our numbers somewhat).

Perhaps the saddest bars on both charts are those for Greece. Running structural fiscal surpluses, in an economy at the zero bound and with 27 per cent unemployment, would not normally be considered sensible. But that is what happens when a country loses market access, and yet lingers on in a straitjacket like the euro. I stand by my assertion a month or two ago that there is no politically acceptable deal (politically acceptable in both other countries and in Greece) that can allow Greece to stay in the euro and yet begin to make material ground reversing the catastrophic loss of output and the appalling unemployment rate. It increasingly looks as though the break is coming soon. When and if it does, it will be messy for a time, but it finally offers a way back towards a more fully-employed economy.