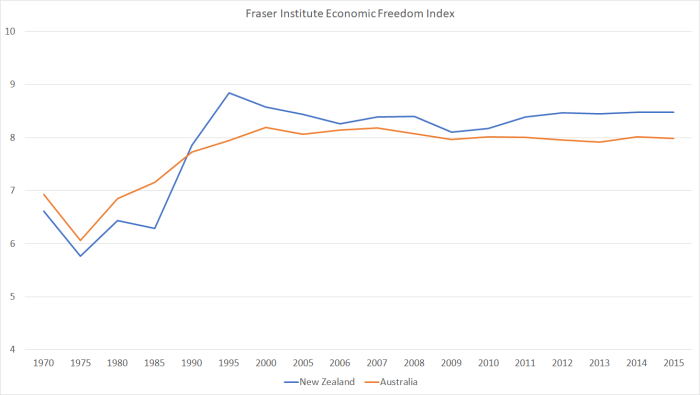

On Friday, I illustrated (again) just how large and persistent the gap between New Zealand’s long-term interest rates and those in other advanced countries has been. If anything, that gap has been larger in recent years (say, since 2009/10) than it was in the previous decade, but there has certainly been no sign of the gap shrinking. It is at least as large now as it was 20 years ago.

Previous posts have illustrated that the gap is large and persistent however one cuts the data. It exists whether one looks just at the big advanced economies (my charts on Friday focused on G7 countries) or just at the small ones (places like Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and Israel). Short-term interest rates are more variable than long-term ones, but on average the gap exists in short rates as well as long rates. (If you aren’t convinced of the relationship between short and long rates, here are the average short and long-term interest rates for the last decade for each of the 18 OECD monetary areas – ie countries with their own monetary policies, plus the euro-area as a bloc).

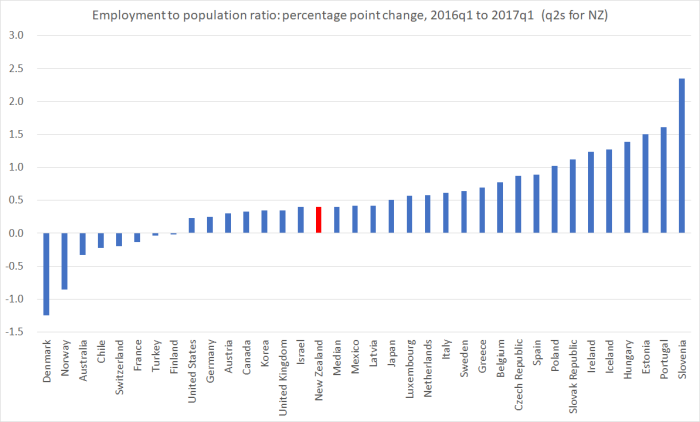

(The country on the far right of the chart is Iceland.)

Today’s post and tomorrow’s are about why those large and persistent gaps exist. They will repeat material I’ve covered in earlier posts over the years, but readers come and go, old posts can be hard to find, and the issue hasn’t shown any signs of going away. Much of today’s post is about a process of elimination: clearing away various possible explanations that, on my reading of the evidence, don’t take us very far.

10 years ago, the Reserve Bank wrote a short paper on exactly this issue. It was part of our submission to the inquiry being undertaken into monetary policy by Parliament’s Finance and Expenditure Committee. I wrote the paper, but it was of course signed out by the powers that be, including the then Governor Alan Bollard and his deputy Grant Spencer. Rereading it this morning, I don’t now agree with every word of that earlier document – partly because my own thinking has gone beyond where we had got to then – but it still does a good job of laying the foundations. I’d be surprised if today’s Reserve Bank sees any reason to disavow that 2007 interpretation.

In writing the earlier paper, one of our main concerns was to distinguish between things the Reserve Bank could sensibly be held responsible for and things that really had little or nothing to do with us. In particular, so we argued, the Reserve Bank sets the OCR, and expectations about the future OCR affect longer-term interest rates, but that does not mean that over prolonged periods of time the Reserve Bank gets to decide the average level of real interest rates in New Zealand.

In a mechanical sense, then, if short-term interest rates are persistently higher than those in other countries it is because the Bank put them there. However, the OCR is not set arbitrarily. Rather, the Bank looks at actual inflation outcomes, and at all the data on the outlook for inflation, before setting the OCR with the aim of keeping inflation comfortably inside the target range over the medium-term. If the Reserve Bank was consistently setting the OCR too high, we would expect over time to see inflation averaging towards the bottom end, or perhaps below the bottom, of the target range. In fact, inflation has consistently averaged in the upper half of successive target ranges – this decade, for example, inflation has averaged 2.6 percent. If monetary policy had been set consistently too tight, the solution would be easy. But there is no sign of that.

It has, at times, been argued that New Zealand’s inflation target was too ambitious and that this might explain why New Zealand’s interest rates have been persistently higher than those in other countries. In the early years of inflation targeting, our inflation target was lower than those in other countries, but …… our target (midpoint at 2 percent) has been firmly in the international mainstream. The most common developed country inflation target (actual or implicit) is around 2 percent. ……there is no convincing reason why achieving an inflation target of around 2 percent should, over time, be any more demanding in New Zealand than it is in other developed countries.

One thing has changed since then. (Core) inflation has been averaging a bit below the target midpoint, but even so the average inflation rate here over the last five or ten years has been very similar to that in the typical (median) advanced economy. Monetary policy settings that have been a bit tighter than necessary can, at most, explain only a small part of the average gap between New Zealand and international interest rates (nominal and real).

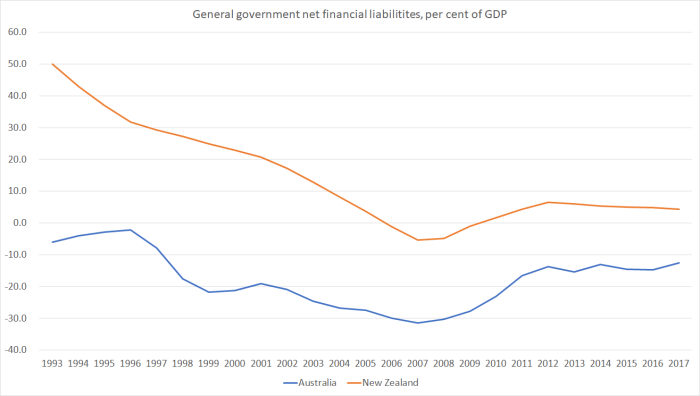

As we pointed out 10 years ago, credit risk wasn’t a compelling explanation either. That story feels even more robust today than it did then. Our government finances aren’t the very strongest in the entire OECD, but they are among the best. And the negative net NIIP position (the net indebtedness of all New Zealand entities to the rest of the world) is smaller, as a share of GDP, than it was 10 years ago. Plenty of observers worry about high levels of private sector credit but (a) as a share of GDP it isn’t much different now than it was 10 years ago, and (b) the crisis literature tends to worry more about quick increases in debt ratios at least as much as high levels.

(Small) size isn’t really much of an explanation either. There are a couple of possible strands to a story about size. The first would be something about secondary market liquidity. The New Zealand government bond market is tiny in comparison to those of, say, the United States, Japan, France, Italy, or even Germany. That makes it difficult, or expensive, to offload a very large position, and might (in principle) given rise to an additional “illiquidity premium” in our long-term interest rates.

In practice, it doesn’t seem likely to be a material part of the explanation. Over the last decade, for example, our real interest rates have been about as much above those of the small well-managed OECD countries as they have been above those of the G7 countries. And the “illiquidity premium” is a story that should apply to bond rates more than to overnight rates and yet over the last few decades our short-term rates have been higher relative to our long-term rates than has been the experience of most other advanced countries. Over the last decade, interpreting that relationship has been made more difficult as many other countries had short-term rates near-zero and felt unable to take them any lower even if they’d wanted to. But even over the last decade, there has been no sign that New Zealand’s long-term interest rates have been surprisingly high, given where short-term rates were.

I covered off another possible small country story in a post last November

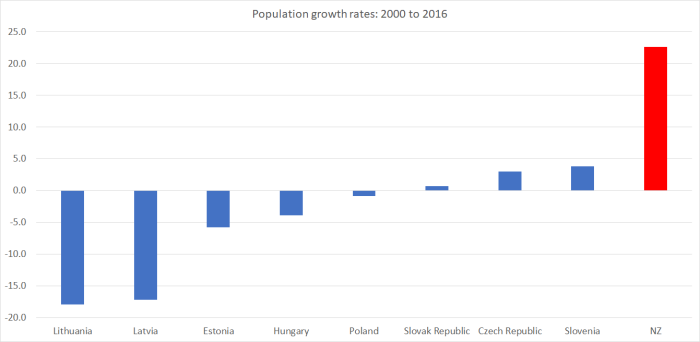

There is another possible story which hasn’t really entered the mainstream of the New Zealand debate, but should be covered off for completeness. It notes that New Zealand is a small country, with quite a volatile terms of trade, and that the currencies of such countries offer less-good diversification opportunities, suggesting that anyone investing here would require a higher return than elsewhere. It sounds initially plausible, but it has a number of problems. The first is that our interest rates have been persistently higher than those in other not-large countries with their own currencies …… And the second is that if this were an important channel, it would suggest that small countries face a higher cost of capital than large ones, which would limit the growth prospects of small countries. But (badly as New Zealand specifically has done) there is no real sign that small countries typically grow (per capita, or per hour worked) more slowly than large ones. At present, I don’t think it is a particularly strong candidate to explain New Zealand’s persistently high interest rates. Apart from anything else, if this were the story, why would New Zealand have accumulated – and maintained – such a large negative net international investment position (NIIP) (still among the largest of the OECD countries)?

Monetary policy doesn’t explain the gaps, and neither do size or credit risks considerations. Here was the Reserve Bank summary a decade ago

Standing back, it seems unlikely that factors such as credit risk, size and market liquidity help very much at all in explaining the persistent gap between our real interest rates and those in other developed countries. Apart from anything else, if these factors were (collectively) an important influence, we would expect to see New Zealand firms and household taking on less debt than those in other countries. In fact, of course, one of the well-recognised facts about New Zealand is that our households are highly indebted by international standards, and that the nation as a whole has been unusually willing to borrow, and raise equity capital, from abroad.

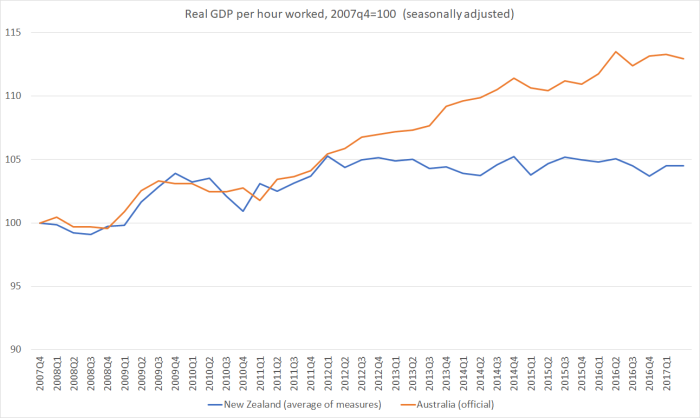

Productivity growth doesn’t help as an explanation either.

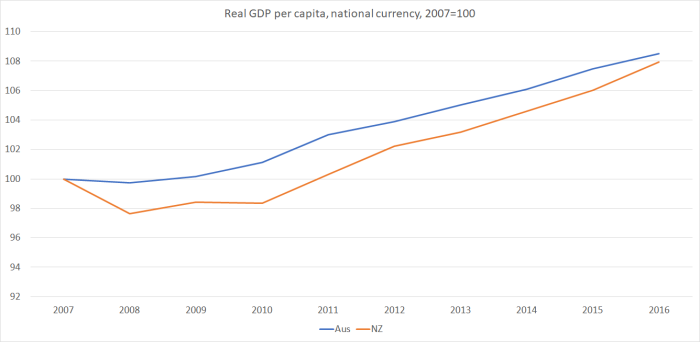

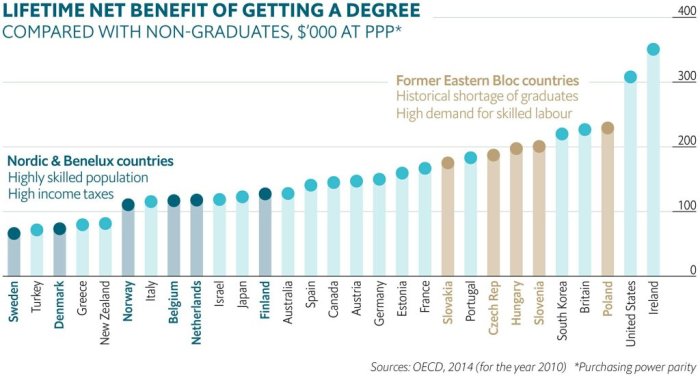

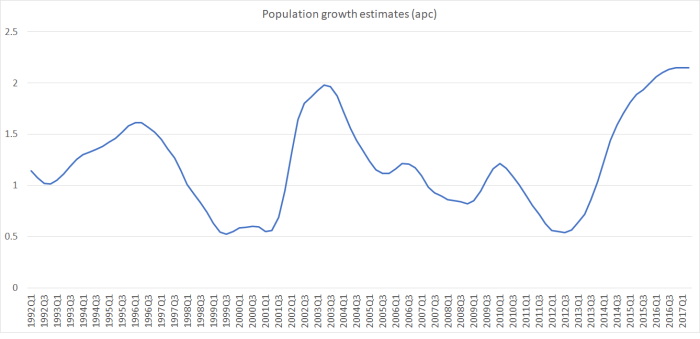

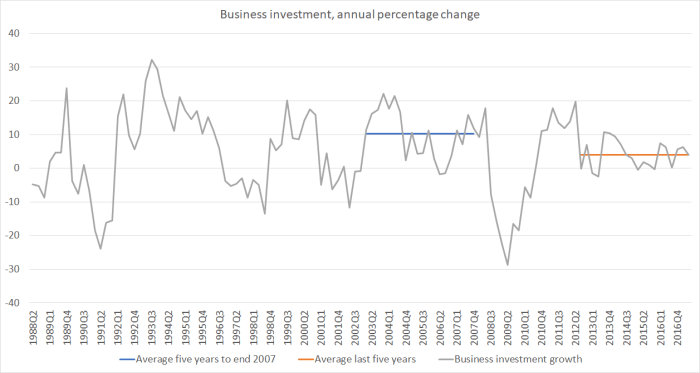

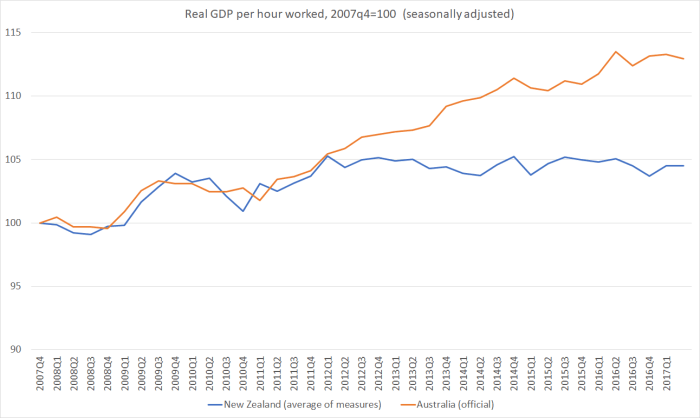

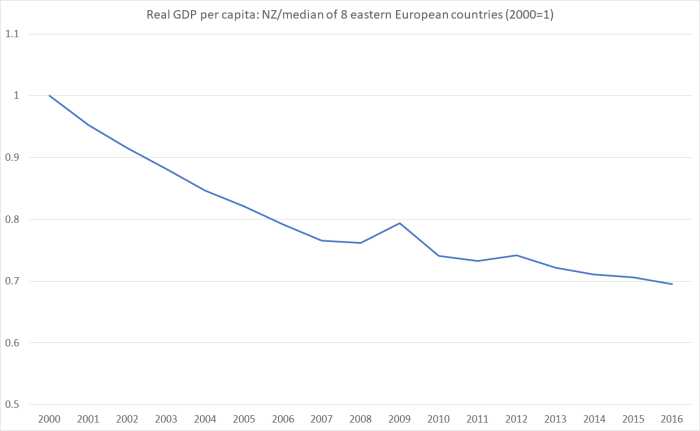

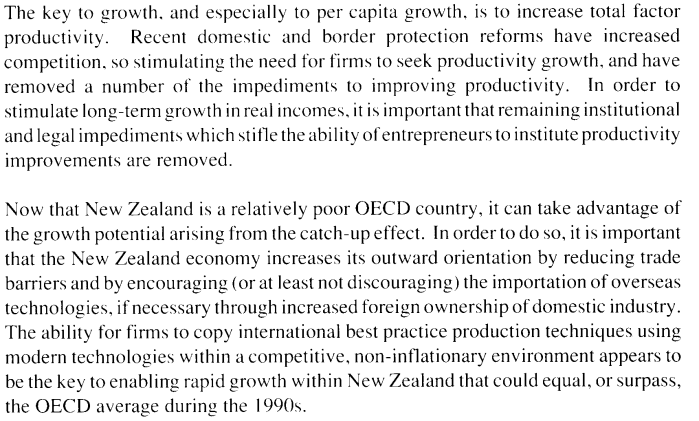

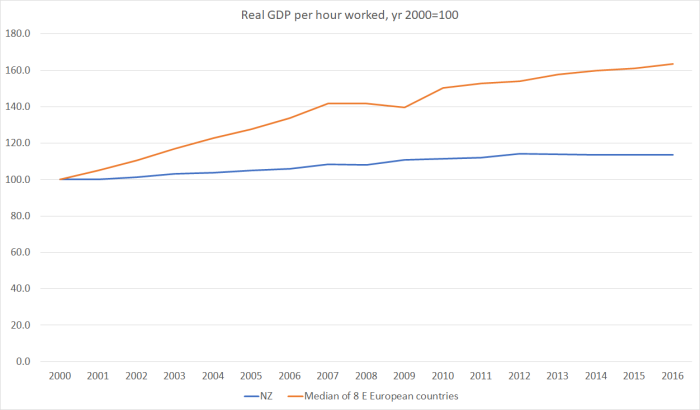

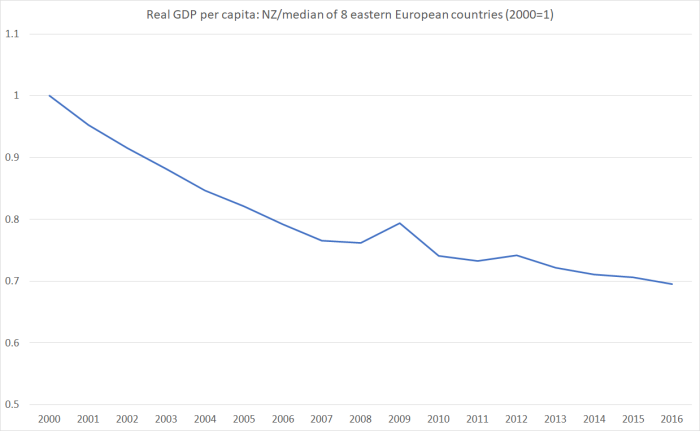

If a country had very strong persistent productivity growth it would, all else equal, tend to have higher interest rates than would be seen in other countries. There would be lots of profitable investment opportunities in that high productivity growth country, lots of (expected) income growth that people might be consuming in anticipation of, and so on. And over time, that high-productivity growth country could expect to see its real exchange rate rise. Unfortunately, high productivity growth isn’t the story of New Zealand in the last few decades. Indeed, more often rather the reverse. Over the last five years, we’ve recorded no labour productivity growth at all. Over the last 10 years, at best we’ve only been around a middling OECD country for productivity growth, and over longer-terms still we’ve had one of the worst records anywhere. I illustrated a few months ago, the depressing comparisons of productivity growth between New Zealand and the emerging economies of central and eastern Europe.

A more prominent explanation for New Zealand’s persistently high interest rates points to the large negative NIIP position and asserts that the explanation for high interest rates is pretty straightforward: lots of debt means lots of risk, and hence the need for a substantial risk premium on New Zealand interest rates. Taken in isolation – if someone told you only that a country had a large negative NIIP position this year – it might sound plausible. Once you think a bit more richly about the New Zealand experience it no longer works as a story.

Here was the Reserve Bank commentary on this possible story a decade ago.

But the fact that this correlation exists between net international positions and local interest rates does not explain very much at all. In particular, it does nothing to explain what leads countries such as New Zealand to take on such large amounts of foreign capital in the first place. More specifically (and given that the Crown now has no net debt), what motivates New Zealand firms and households to take the actions that lead to this accumulation of foreign capital? And having accumulated the foreign liabilities (and New Zealand’s, as a share of GDP, have not changed much in a decade), what makes higher interest rates sustainable here for prolonged periods?

First, our NIIP has been large (and negative) for a very long time now – for at least the last 25 years, and over that time there has been no persistent tendency for the NIIP position to get better or worse for long. By contrast, 20 years earlier than that New Zealand had almost no net foreign debt. The heavy government borrowing undertaken in the 70s and 80s had markedly worsened the position. It is quite plausible that foreign lenders might then have got very nervous and wanted a premium ex ante return to cover the risk. In fact, we know some (agents of) foreign investors got very nervous – there was the threat of a double credit rating downgrade in early 1991. But when lenders get very nervous, borrowers tend to change their behavior, voluntarily or otherwise, working off the debt and restoring their creditworthiness. And in New Zealand, the government did exactly that – running more than a decade of surpluses and restoring a pretty respectable government balance sheet. But the large interest rate differential has persisted – in a way that it did in no other advanced country (including those that went through much worse crises and threats or crises than anything New Zealand has seen in the last 25 years).

As I’ve already touched on, short-term interest rates are set by the Reserve Bank, in response to domestic inflation pressures. But long-term interest rates are set in the markets. If investors had really been persistently uneasy about New Zealand’s NIIP position, we might not have seen it much in short-term interest rates, but should certainly have expected to see it in the longer-term interest rates. (That, after all, is what we see in various euro countries that have lapsed in and out of near-crisis conditions). But in one obvious place one might look for direct evidence of such a risk premium, it just isn’t there.

And remember that when risk concerns about a country/currency rise, one of the first things one typically sees – at least in a floating exchange rate country – is a fall in the exchange rate. It is a bit like how things work in equity markets. When investors get uneasy about a company, or indeed a whole market, they only rarely succeed in getting higher dividends out of the company(ies) concerned. If the companies were sufficiently profitable to support higher dividends the concerns probably wouldn’t have arisen in the first place. Instead, what tends to happen is that share prices fall – and they fall to the point where expected dividends, and the expected future price appreciations of the share(s) concerned, in combination leave investors happy to hold those shares. In that process, an increased equity risk premium is built into the pricing.

At an economywide level, if investors had had such concerns about the New Zealand economy and the accumulated net debt position, the most natural places to have seen it would have been in (a) higher long-term bond yields, and (b) a fall in the exchange rate (and perhaps a persistence of a surprisingly weak exchange rate). But we’ve seen neither in New Zealand. Had we done so, presumably domestic demand would have weakened, and net exports would have increased. The combined effects of those two shifts would have been to have reduced the negative NIIP position, and reduced whatever basis there had been for investors’ concerns. Nothing in the New Zealand experience over the last 20 years or more squares with that sort of story.

And that is the really the problem with the most common stories used to explain New Zealand’s persistently high interest rates. They simply cannot explain the co-existence of high interest rates and a high exchange rate over long periods.

My story attempts to. More on that tomorrow.