For the leader of the National Party, Bill English, that is, for announcing yesterday that if his party is in government after September’s election it will seek to

(a) lift the residency requirement from 10 years to 20 years, starting some way down the track, and

(b) lift the age of eligibility for New Zealand Superannuation from 65 to 67, but not starting until 2037.

It is a topsy-turvy political world in which at the last election the National Party was campaigning on, in essence, no changes to NZS ever (talk of everything being “affordable” for the next 50 years), while the Labour Party was campaigning on a rather faster move to age 67 than the National Party is proposing now. But now the Labour Party appears staunchly opposed to any increase in the eligibility age. Perhaps if Bill English and David Cunliffe had held the reins at the same time, a cross-party accord might have been in prospect?

It is also a bit odd when media start talking as if political promises made today, even if enacted next year, actually make very much difference to what will happens in 2037 and beyond. For all the talk of “giving people certainty”, it is most unlikely National will be in office for the next 20 years and all-but-certain that Bill English won’t be. Office-holders change, and so do circumstances.

In 1859, no one really envisaged the Land Wars, gold rushes, or the massive transfomative effects of the Vogel public works and immigration programmes.

In 1879, no one was probably planning on having a state age pension at all (let alone the economic opportunities of refrigerated shipping etc). That came in 1898.

In 1899, no one was expecting World War One, and the huge toll of lives and money that took.

In 1919, no one was expecting the Great Depression, or an overhang of debt so severe the New Zealand government defaulted on its domestic debt, and almost had to do so on its foreign debt.

In 1939, even if people anticipated war, they probably neither conceived of one as long and devastating as it was (globally), or that over the following couple of decades New Zealand would enjoy high commodity prices, and end up with very little public debt.

In 1959, few people probably planned on the basis on the “end of the golden weather” – the severe and sustained fall in our terms of trade over the late 60s and especially in the mid-late 70s, that undermined fiscal prospects and opportunities for improved living standards.

In 1979, probably not many envisaged Think Big as the massive fiscal disaster it was, or the disruption (and loss of revenue) that the (overdue) economic reform and liberalisation process would entail.

In 1999, well…..perhaps there have been fewer disruptions in the last couple of decades (even allowing for earthquakes and a serious recession). But it seems unlikely that history is ending.

No one knows what the next 20 years hold, for good or ill, and it would be crazy for anyone to plan today based on a political party’s promise of what welfare payments might be available 20 years hence. My (considerably younger) wife was stunned to learn yesterday that if the new proposed policy carries through she will be eligible for NZS at 65. Since anything can happen in 20 years, I discouraged the idea of starting planning for an extra overseas holiday

And government plans and policies do change, often considerably. In the late 80s, the then Labour government announced a very slow increase in the NZS age, only to have that overturned (and rapidly accelerated) by an incoming government only two years later. And in the 25 years from the early 1970s to the late 1990s, we went through numerous, quite substantial, changes in NZS policy, each no doubt intended by the governments that proposed them as “providing certainty”.

If the National Party really thinks change is needed, they should have promised something that might have involved gradual increases in the eligibility age starting in the next term of Parliament – age-indexed beyond that. If not, they should have bequeathed the issue to their successors.

My own view, outlined in a couple of posts late last year, is that the case for changing the NZS eligibility age (and residence requirement) isn’t primarily one about future fiscal balances. As I noted when the Treasury released their long-term fiscal statement,

Treasury included this chart in the report.

As I noted then, one could reasonably run this under a headline “no urgent need for any big fiscal changes for 20 years”. On these projections, in 2035 the spending share of GDP would be around where it was five years ago. Actual fiscal policy changes happen all the time, and the base on which revenue is raised changes too. It wouldn’t take much for spending as a share of GDP in 2035 to be not much different from where it has been on average over the last decade. One can’t reasonably generate “fiscal crisis” headlines – or urgent official advice to ministers – out of that sort of scenario.

And perhaps that is the sort of thinking the National Party had in mind. There just isn’t a pressing near-term fiscal issue (although, of course, taxes could be lower, or the money spent on other priorities).

My take was different.

To my mind, issues around New Zealand Superannuation are substantially moral in nature, and the debate would be better if centred on those dimensions, rather than on fiscal policy. Our level of government debt isn’t that low, but by international standards it isn’t high either, and if anything looks likely to drop as a share of GDP over the next few years. So the issue shouldn’t be “can we afford to pay a universal welfare benefit to an ever-increasing share of the population?” – ever-increasing, on the assumption that adult life expectancy continues to increase. We probably could. But rather “should we?”, or “is it right to do so?”. Economists quickly get uncomfortable with “is it right” type questions, sidelining them as “political choices”, but almost all the important political choices are about conceptions of what sort of society or government we want – competing visions of what is “right”. Of course, there are practical dimensions, and areas where experts can offer technical perspectives – eg the implications of particular choices for other things we care about (eg labour force participation, incentives to save etc) – but the key choices shouldn’t really be seen as technocratic in nature.

For me, there is simply something wrong about offering a universal income to an ever-increasing share of the population. Governments don’t exist to support us all,

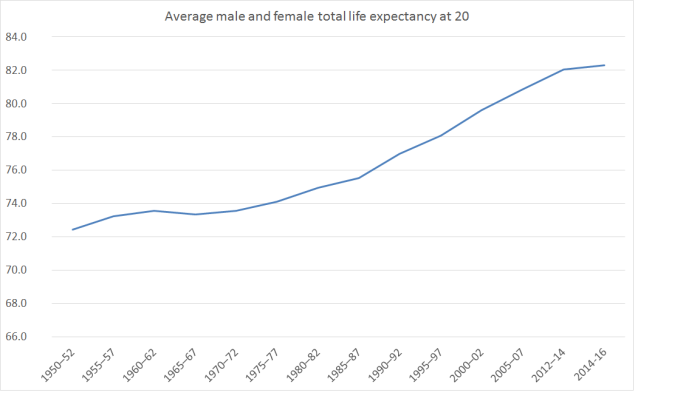

From the SNZ life tables, we can trace changes in life expectancy since 1950. Here I’ve shown life expectancy for those reaching age 20 (ie old enough to have reached the workforce).

The observations aren’t always evenly spaced (especially towards the end), but over the full period, of 64 years, average (across male and female, Maori and non-Maori) life expectancy for people who get to age 20 has increased by 9.8 years – about 1.5 years per decade.

At the first observation, centred on 1951, life expectancy at birth for males was only around 67.2 years. Too many died very young – in 1948 (the first year with data on Infoshare), just over 10 per cent of all male deaths were of children under 5. But around 1950 a large chunk of the men who reached adulthood, and the taxpaying years, still died before they were 65 (around a third of all male deaths of those over 20 occurred before age 65. The female numbers weren’t that much lower. None of those people lived to collect a state pension payable from age 65.

By contrast, in 2015 only 18 per cent of adult deaths occurred before age 65.

It is quite true that, on SNZ estimates, life expectancy at 65 has not increased as rapidly as overall life expectancy (up 6.6 years over 64 years), or even that at age 20.

But the fiscal burden doesn’t just arise from how long people live once they get to 65, but what proportion of adults get to age 65 at all.

Here is a chart showing life expectancy at 20, and the NZS eligibility age. The final two dots are what might have happened by 2040 if the life expectancy gains continue at the same rate as since 1950, and the NZS eligibility age if yesterday’s National Party policy proposal comes to pass.

Over that full period, 90 years, the NZS eligibility age would have risen by two years, and adult life expectancy (those getting to 20) would have increased by about 13.5 years. By 2040 it will be amost 40 years since the NZS age got back to 65. In that time, adult life expectancy is likely to have risen by 5 to 6 years, and yet the NZS age will have risen only by two years, if the new National Party policy is implemented.

Something seems bad out of whack there, and that is before allowing for the fact that the typical person now enters the fulltime workforce considerably later than they did in earlier decades: many fewer leave school at 15, and now most do tertiary education as well. The period the typical adult will be receiving NZS for, as a share of their time in the workforce (paid, or raising children) just keeps on rising. And that seems wrong. For some, no doubt, working until 67 or beyond would be physically difficult, or impossible. In the past, for very many, even living to 65 was aspirational.

Overall, National’s proposal yesterday was a pretty feeble one. Better than Labour’s stance – which seemed to involve potentially reducing future pensions, but not increasing the age – but so far in the future it should probably be discounted back to very little. Perhaps it would have deserved a little more credit, if they had been willing to embrace – and campaign on- the notion of formally indexing future increases in the eligibility age to future changes in life expectancy. But they couldn’t even manage that, not even for the hypothetical adjustments that might occur in the decades after 2040.