How natural resources contribute to the prosperity of nations is much-debated. There is little doubt that a) natural resources can be wasted, mismanaged etc, such that a country well-provided for by nature still ends up pretty poor (Zambia is my favourite example, partly because I worked there), and b) that it is perfectly feasible for some countries to do very well indeed with little in the way of natural resources (one could think of Singapore or Japan, but also Belgium or Switzerland). The quality of the human capital of the people in a place, and the “institutions” that are put in place or sustained, make a huge difference. Location looks as though it might matter too.

But equally, it is easy to think of countries where it is pretty clear that natural resources have made a great deal of difference indeed in lifting the economic prosperity of the nation. One could think of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Brunei, Equatorial Guinea and so on. It isn’t natural resources in isolation that makes them rich – Iraq and Iran still manage to mess themselves up – but in combination with some basic level of property rights, institutional quality, and human capital (native or imported) the natural resources have lifted living standards in such countries above levels that could otherwise readily be explained.

The quantity of natural resources in each country is fixed. That doesn’t mean that what can be done with those resources is fixed – able people and smart technologies find more efficient ways of extracting the resources or utilising them. We’ve seen that in New Zealand with the growth of agricultural sector productivity over 150 years or more. But the fact that the endowment is fixed means that each additional person added to the country reduces the average per capita value of that endowment. If the natural resource stock is small to start with, it isn’t a point worth bothering about (and so a lot of economic models largely ignore fixed factors). But if it is a large part of what an economy produces, and exports, it can matter rather a lot. It is why I’m unconvinced that rapid immigration policy driven population increase makes a lot of sense in New Zealand or Australia, where the overwhelming bulk of what we sell abroad is natural resource dependent. The point is more immediately pressing in New Zealand – where we haven’t uncovered major new natural resources for a long time – than in Australia, but is no less conceptually relevant there.

In this post, I wanted to illustrate the point by looking at the experience of Norway and Britain with North Sea oil and gas. The oil and gas were always there, but weren’t known about for most of history – and even if they had been known about, it wasn’t until offshore drilling and processing technology got to a certain point that the resources had much value. By the 1970s, Britain and Norway were beginning to get into oil and gas production.

Britain and Norway were both advanced economies in 1970, drawing on the skills and talents of their people and growth-friendly institutions and cultures. Natural resources probably matter a bit more in Norway, but oil and gas weren’t then among those resources. And in 1970, OECD data indicate that GDP per hour worked in the two countries (converted at PPP exchange rates) were about the same. As it happens, GDP per hour worked in New Zealand then was around the same level.

These days, by contrast, GDP per hour worked in Norway is around 60 per cent higher than that in the UK (which is in turn quite a bit higher than New Zealand’s). Norway has among the very highest material living standards of OECD countries, and the UK is still in the middle of the pack.

These days, by contrast, GDP per hour worked in Norway is around 60 per cent higher than that in the UK (which is in turn quite a bit higher than New Zealand’s). Norway has among the very highest material living standards of OECD countries, and the UK is still in the middle of the pack.

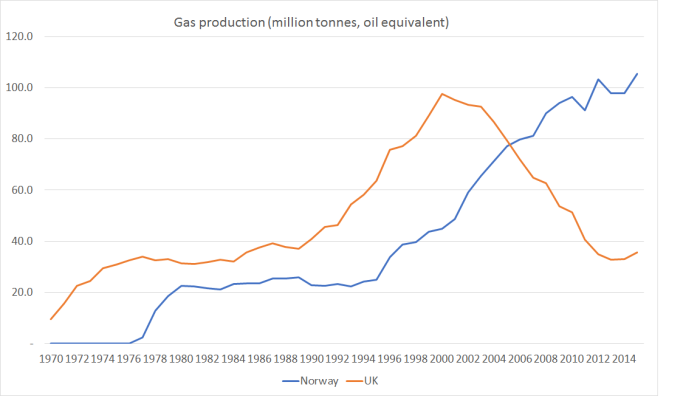

Here are the charts for total oil and gas production in the two countries since 1970, using data taken from the BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

First oil

And then gas

Over the 40 years to 2015, the two countries each produced roughly the same amount of oil and the same amount of gas.

There are all sorts of differences between the two countries. I’ll come back to some of those, but the first I wanted to emphasise was population. Norway now has around five million people, and the UK currently has around 65 million.

Here is per capita oil and gas production for the two countries.

That “windfall” – the discovery of large recoverable oil and gas resources – made a big per capita difference in lightly populated Norway, and not much of one in heavily-populated Britain.

Determined sceptics might argue that it is all a mirage and that somehow Norway would have got to its current living standards anyway. If I was focusing on GDP per capita they could, for example, point out that in Norway a materially larger share of population is employed than in the UK. But, as it happened, I was focusing here on GDP per hour worked (and if anything, employing a higher share of the population should probably lower, at least a bit, average output per hour, if the less productive people are the last to be draw into the workforce). As it happens too, the employment/population gap between Britain and Norway is narrower than it was in 1970.

Perhaps too people might set out looking for areas in which Norwegian policy is superior to that in the United Kingdom. But there isn’t much to find. As a share of GDP, for example, government spending in Norway has typically been larger than it is in the UK.

And I went through the structural policy indicators released last week as part of the OECD’s Going for Growth. Norway isn’t badly run by any means, but on a majority of the indicators Norway scores less well than the UK.

Location probably favours the UK as well – the south of England is very close, and accessible to, the high productivity populous countries of France, Belgium, Netherlands, Germany. Norway isn’t remote – certainly not by New Zealand standards – but it isn’t quite as advantageously located for prosperity as the UK is.

In sum, don’t think any dispassionate observer would doubt that oil/gas – combined with the responsible management of the revenue – is what explains Norway’s rise over the last few decades to the top of the OECD league tables. And if, by some historical chance, there had been 65 million people living there, rather than the five million who actually were, it just wouldn’t have made very much difference. For the UK, the oil and gas were a “nice to have”. For lightly-populated Norway they made a great deal of difference.

For New Zealand, for whom extreme remoteness is a given, and where fixed natural resources make up so much of our export earnings, it is something to think about. There is a reasonable alternative story to tell under which the average New Zealander would have been better off – given the current state of global and local technology etc – if there were three million of us not 4.7 million. Perhaps that would have been the case, if we hadn’t restarted large scale immigration after World War Two.