New Zealand’s interest rates have been higher than those in the rest of the advanced world for decades. Making sense of why is one element – I argue an important one – in getting to the bottom of why New Zealand’s relative economic performance has been so poor, and in particular why we’ve made up no ground relative to most other advanced countries in the last 25 years or so. Our productivity growth has been slower than that of most other advanced countries, and after a disastrous few decades we entered the 1990s already less well off than the typical advanced country.

If we had good comparable data for the earlier decades (say 1950s to 1970s), and market prices had been free to reflect underlying pressures, our interest rates would have been higher than those in the rest of the advanced world then too. Instead, we made much greater use of direct controls (on imports, credit, foreign exchange flows) than most advanced countries did. We don’t really get comparable interest data again until the mid 1980s.

When I say that our interest rates have been higher than those in other advanced countries, I really mean “real” interest rates. Differences in inflation rates really complicate the picture at times in the past – in the 1970s and 1980s for example, New Zealand had some of the highest inflation rates in the advanced world. But over the last couple of decades, inflation rates have been much lower and much more stable, across time and across countries. I could spend a great deal of time constructing estimates of “real” interest rates, but none of them would be ideal (eg there are no consistent cross-country measures of inflation expectations) . And so the charts I’m showing in this post, will use nominal interest rates. Where relevant, I will mention changes in inflation targets, actual or implicit.

And when I say that our interest rates have been higher than those in other advanced countries, I don’t necessarily mean “in every single quarter, against every single country”, but on average over time (actually, in the overwhelming majority of quarters, against the overwhelming majority of countries). New Zealand’s OCR actually got as low as the US federal funds rate target in 2000 (both were 6.5 per cent), but it didn’t last more than a few months. Changes in inflation targets do make a bit of a difference: in the early 1990s for example, we were targeting 1 per cent inflation. Australia didn’t have an explicit target at all for a while, and when they adopted one it was centred on 2.5 per cent. So our nominal short-term rates were somewhat relative to theirs in the early 1990s. Adjusting for (say) differences in inflation target, our policy rates have been higher than theirs throughout the last 20 years, with the exception of the peak of mining investment boom.

The point of this series of posts isn’t really to establish that our interest rates are, and have been, higher than those in other advanced countries. No one seriously contests that. But just to illustrate the point briefly, here are a couple of view ofs the long-term bond yield gap.

One line shows the gap between New Zealand and the median of the all the OECD countries for which there is data since 1990 (ie mostly excluding the eastern European countries), and the other is the gap between New Zealand and the median of Australia, Canada, Sweden and Norway, four not-large countries that control their own monetary policy.

The gap is larger than it was in the early 1990s – when we had an unusually low inflation target – and even if you take just the last 20 years (or even the last 10) there is no sign of the gap narrowing. There are cyclical fluctuations, of course, but our long-term interest rates are well above those in other advanced countries (with mostly quite similar inflation targets).

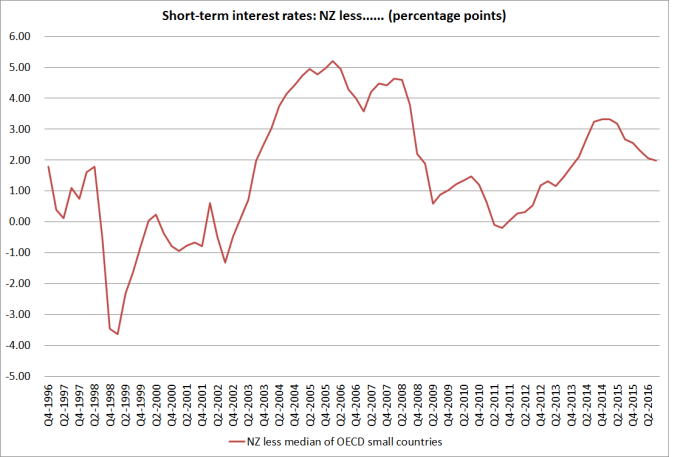

And here is the same chart for short-term interest rates (again, OECD data).

Again, no sign of any convergence occurring. Even the latest observations (on which almost no weight should be put – rates fluctuate) aren’t much different from the averages for the last 20 years.

And since commenters sometimes highlight small countries, here is the short-term interest rate gap between New Zealand and the median of the seven smallest OECD countries that have their own monetary policy for the last 20 years (a period for which the OECD has data for all of them).

So our interest rates (a) are and have been higher than those abroad, (b) this is so for short and long term interest rates, (c) is true even if we look just at small countries, and (d) is true in nominal or real interest rate terms. And the gap(s) shows no sign of closing.

But the really interesting question isn’t whether our interest rates are higher, but why. That will be the focus of the next post.

Well that was short… bit of a teaser really… The focus is rightly on real interest rates, so inflation should not figure that much in the discussion??

Some possibilities – narrow commodity based exports, small country and remote (unlike small European countries we don’t have some 500m people living close by), exchange rate driven by commodity price swings, credit rating differentials, productivity gaps (already fingered), over tightening by the RB…

Looking forward to part 2

LikeLike