If Steven Joyce had simply noted that the Labour Party appears to have made so many specific policy promises that if they were to form the next government it would be very hard to deliver on those specific policy commitments, meet ongoing increases in the cost of normal government activities, and yet at the same time meet the specific spending, surplus, and debt numbers they’ve outlined in their fiscal plan, a useful and constructive exchange might well have followed. My summary stance: I think that looks like a reasonable conclusion. How much it matters probably depends largely on how much weight you put on the importance of those surplus and debt numbers.

I didn’t read the Labour fiscal plan when it was released. The specific policy promises had already been announced and in an MMP era, in particular, documents of this sort always seem like not much more than opening offers going into potential negotiations around the formation, and conduct, of a new government. They also involve a degree of ritual obeisance to the belief that economic forecasts have much value; a ritual belief that while entirely conventional leaves me cold (whether opposition parties or government agencies are doing it).

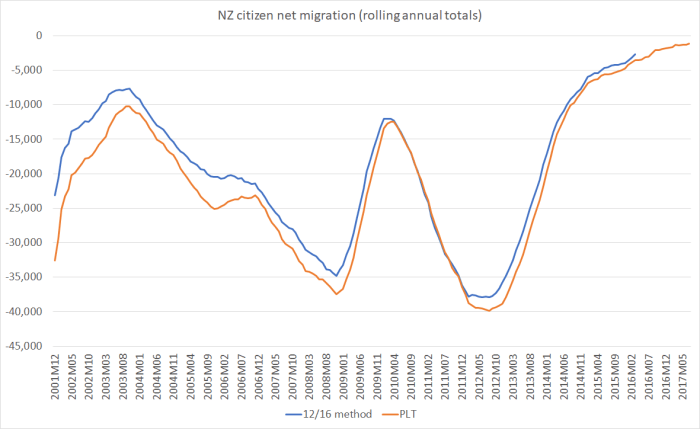

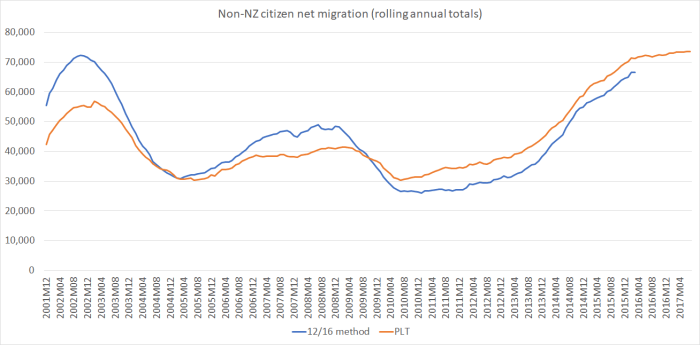

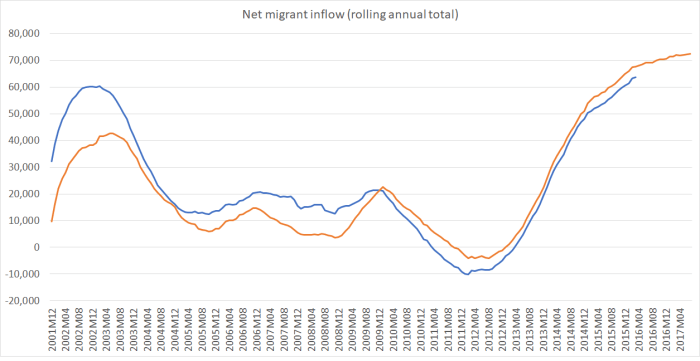

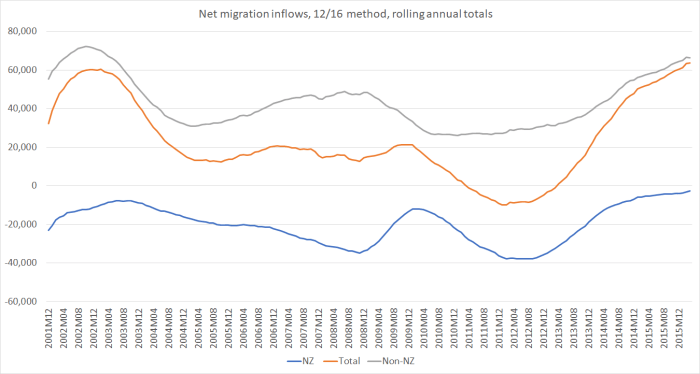

None of us knows what the terms of trade will do over the next few years, or net migration, or the myriad of other things here and abroad that will affect the economic and fiscal outlook. Even the rate of inflation will affect how large the operating allowance should sensibly be each year (since it is nominal – and cost pressures will be different if the Reserve Bank delivers inflation at 1.2% than if it delivers 2.2% inflation). Of course, we want specific promises to be costed, and on a multi-year basis. But this debate hasn’t been about specific policy costings. And beyond that, the amount of information in these documents is really quite limited. Among other things, Labour’s numbers use exactly the same GDP track as in the PREFU, but presumably they expect their wider economic policy measures to make some difference to that (eg somewhat less immigration – at least in the first year – and perhaps appointing a Reserve Bank Governor who might generate a bit less unemployment and a bit more inflation – two measures deliberately used here because they have offsetting effects on nominal GDP).

But, for now, lets play the game.

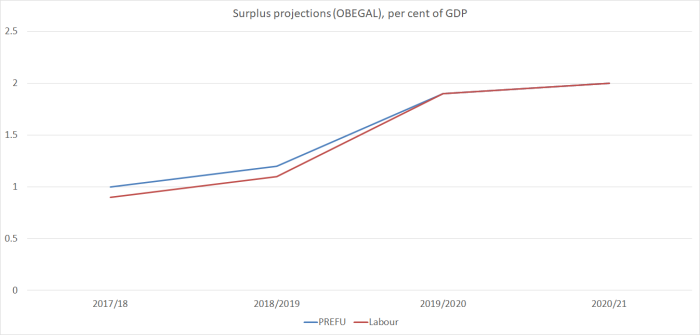

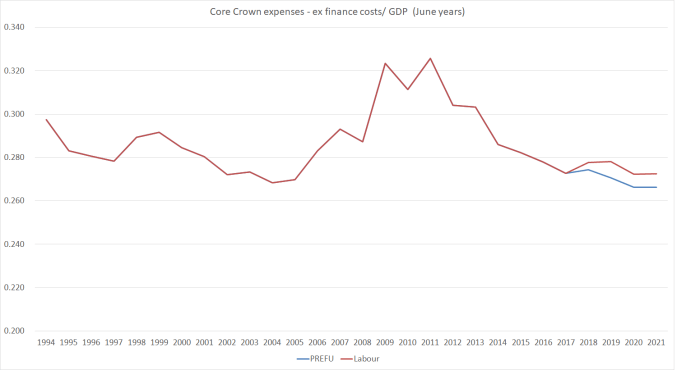

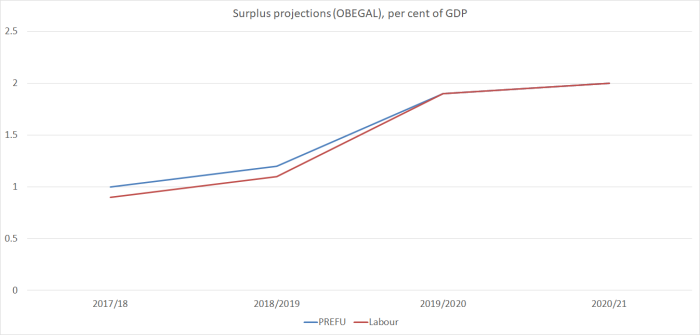

Labour has laid out their numbers in a series of summary tables. They have explicitly identified numbers for each of their (revenue and expenditure) major policy initiatives, and made explicit summary provision for the cost of a group of less expensive policies. And they identified how much (or little) still unallocated money they would plan to have available. The resulting operating surplus numbers are almost identical to those in PREFU, but where they do take on a bit more debt – to fund NZSF contributions and the Kiwibuild programme – they also allow for additional financing costs.

And then they had BERL go through the numbers. People on the right are inclined to scoff at BERL and note that they are ideologically inclined to the left. No doubt. But all they’ve done on this occasion is a fairly narrow technical exercise. They haven’t taken a view on the merits of any specific policy promises or even (as far I can see) on the line item costings Labour uses. And they haven’t taken a view on the ability of a Labour-led government to control spending more broadly. They’ve taken the Labour numbers, and the PREFU economic assumptions and spending/revenue baselines, and checked that when Labour’s spending and revenue assumptions are added into that mix that the bottom line numbers are

consistent with their stated Budget Responsibility Rules and, in particular

- The OBEGAL remains in surplus throughout the period to 2022

- Net Core Crown debt is reduced to 20% of GDP by June 2022

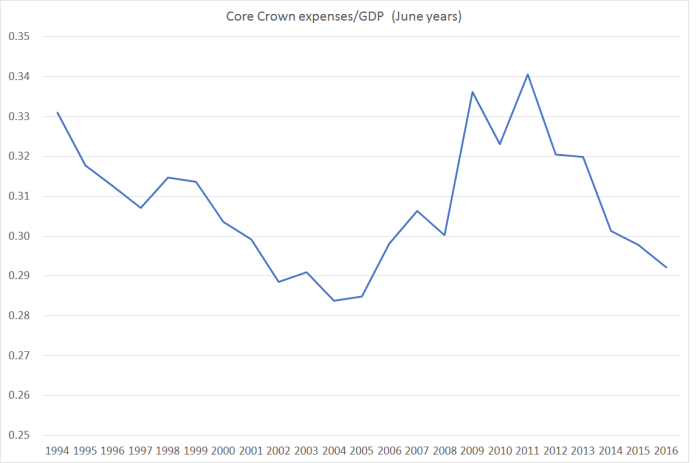

- Core Crown expenses remain comfortably under 30% throughout the period to 2022.

An economics consultancy with a right wing orientation would have happily signed off on the same conclusion. The numbers add up, on the material they were given. In that sense, there is no $11.7 billion “fiscal hole” and the opening claim by Steven Joyce on Monday was simply wrong. Arguably, irresponsibly so from a serving Minister of Finance.

But where there is more of an issue is that Labour’s spending plans on the things they are promising mean that to meet these surplus and debt objectives, on these macro numbers, there is very little new money left over in the next few years. That might not sound like a problem – after all, why do they need much “new money” in the next few years when the things they want to do are already specifically identified and included in the allocated money in the Labour fiscal plan. The answer to that reflects the specifics of how the fiscal numbers are laid out, and how fiscal management is done. Government departments do not get routine adjustments to their future spending allowances to cope with, say, the rising demands for a rising population, or the increased costs from ongoing inflation (recall that the target is 2 per cent inflation annually). Rather, they are given a number to manage to, and only when the pips really start squeaking might a discretionary adjustment to the department’s baseline spending be made. Any such discretionary adjustments comes from the “operating allowance” – which thus isn’t just available for new policies.

You can see in the PREFU numbers. Health spending rose around $600 million last year, and is budgeted to rise by around $700 million this year (2017/18). And then….

|

$m |

| 2017/18 |

16432 |

| 2018/19 |

16449 |

| 2019/20 |

16481 |

| 2020/21 |

16396 |

No one expects health spending to remain constant in nominal terms for the next three fiscal years. But there will need to be conscious decisions made in each successive Budget to allocate some of the operating allowance to health – some presumably to cover new policies, and much to cover cost increases (wages, drugs, property etc, and more people), all offset by whatever productivity gains the sector can generate.

And here is why I think there are questions about Labour’s numbers. By 2021, they expect to be spending $2361 million more on health than is reflected in these PREFU numbers. About 10 per cent of that increase is described as “Paying back National’s underfunding” and the rest is labelled as “Delivering a Modern Health System”.

This is how they describe their first term health policies

Reverse National’s health cuts and begin the process of making up for the years of underfunding that have occurred. This extra funding will allow us to invest in mental health services, reduce the cost of going to the doctor, carry out more operations, provide the latest medicines, invest in Māori health initiatives including supporting Whānau Ora, and start the rebuild of Dunedin Hospital.

That sounds like an intention to deliver materially more health outputs/outcomes (ie volume gains, or reduced prices to users).

In response to Steven Joyce’s attack, Grant Robertson is reported as having told several journalists that Labour’s health (and education) numbers include allowances for increased costs (eg rising population and inflation – and inflation in the PREFU is forecast to pick up) as well as the costs of the new initiatives. Perhaps, and if so perhaps a pardonable effort to put a favourable gloss on the proposed health (and education) spends – ie sell as new initiatives what are in significant part really just keeping with cost and population pressures. I say “pardonable” because governments do it all the time.

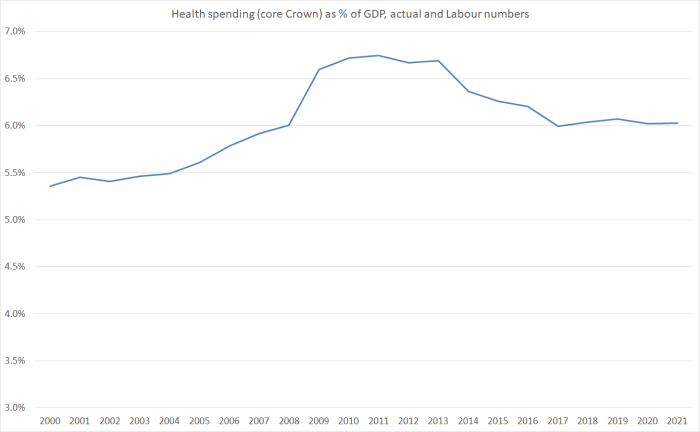

In this chart, I’ve shown core Crown health expenditure as a share of GDP since 2000, and including Labour’s plans for the next three budgets. (Labour show total Crown numbers, but I’ve taken their policy initiative numbers – ie changes from PREFU – and applied them to the core Crown data, which Treasury has a readily accessible time series for. The differences between core and total Crown in this sector are small.)

In other words, on these numbers health as a share of GDP over the next three years would be less than it was for most of the current government’s term, and virtually identical to what it was in Labour’s last full year in government, 2007/08. Some of the peaks a few years ago were understandable – the economy was weak, and recessions don’t reduce health spending demands. But even so, we know that there are strong pressures for the health share of GDP to increase, as a result of improving technology (more options) and an ageing population. Treasury’s “historical spending patterns” analysis in their Long-term Fiscal Statement last year had health spending rising from 6.2 per cent of GDP in 2015 to 6.8 per cent in 2030.

Without seeing more detail than Labour has released there really only seem to be two possible interpretations. Either Labour hasn’t allowed for the ongoing (ie from here) population and cost increases in their health sector spending numbers, or there must be much less in the way of increases in health outputs than the documents seem to want to have us believe (eg “reversing years of underfunding”). One has potential fiscal implications. The other perhaps political ones. Glancing through Labour’s health policy, which seems quite specific, I’m more inclined to the former possibility (ie not allowing for population and cost pressures), but I’d be happy to shown otherwise.

Eyeballing that chart – and as someone with no expertise in health – it would look more reasonable to expect that health spending might be more like 6.5 per cent of GDP by the end of the decade, in a climate where a party is promising more stuff not less, and with no strategy to (say) shift more of the burden back onto upper income citizens.

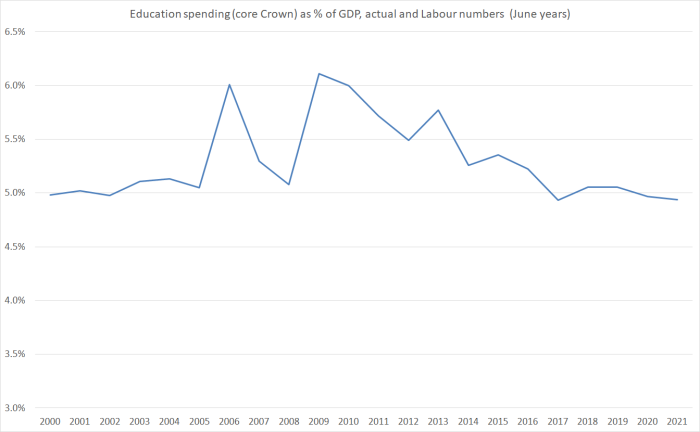

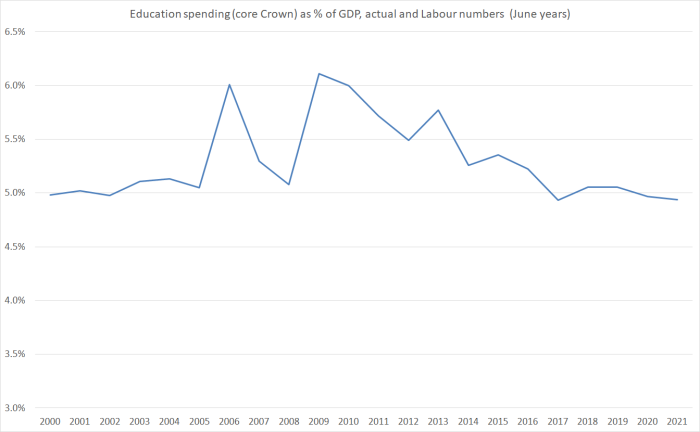

One could do much the same exercise for education. Labour has seven line items in its “new investments” table. Most of them are very specific (including increased student allowances and the transitions towards zero-fees tertiary education). There is a general (large) item labelled “Delivering a Modern Education System” but in the manifesto there are a lot of things that look like they are covered by that. There isn’t any suggestion that general inflation and population cost increases are included, but perhaps they are. But again, here is the chart of education spending as a share of GDP, including Labour’s numbers for the next three years.

I’m not altogether sure what some of those earlier spikes were (perhaps something to do with interest-free student loans), but again what is striking is that Labour’s plans appear to involve spending slightly less on education as a share of GDP than when they were last in government. And that more or less flat track from here doesn’t suggest a party responding to this stuff

National has chosen to undermine quality as a cost-saving measure. After nine years of being under resourced and overstretched, our education sector is under immense pressure and the quality of education is suffering. The result is a narrowing of the curriculum, more burnt out teachers, and falling tertiary education participation.

and at the same time committing to flagship policies around things like student allowances and fee-free tertiary study.

Again, it begins to look as though Labour has included in its education numbers the ongoing multi-year costs of its own new policies, but not the ongoing cost increases resulting from wage and price inflation and population increases. Again, I’d happily be shown otherwise.

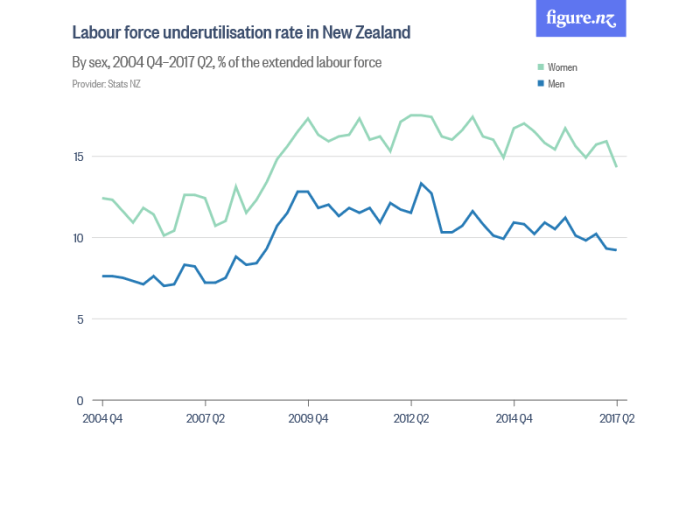

Of course, there is some unallocated spending in Labour’s numbers, but the amounts are very small for the next few years, and some of these sectors are very large. And although population growth pressures are forecast to ease a little in the next few years, inflation is forecast to pick up and settle around the middle of the target range, so there are likely to be increased general cost pressures (including, for example, wage pressures if as Labour state in the fiscal plan document “by the end of our first term, we expect to see unemployment in New Zealand among the lowest in the OECD, from the current position of 13th”).

How much does it matter? After all, we don’t know many specifics on the policy initiatives National (and/or its support partners) might fund in the next term, and there was the strong suggestion the other night of a new “families package” in 2020 (which would come from any operating allowance). Quite probably the next few years will be tough, in budget terms, for whoever forms the government. After all, the terms of trade isn’t expected to increase further, and inflation is. And there is a sense that in a number of areas of government spending things have been run a bit too tight in recent years. On the other hand, Labour participated in this ritual exercise and it looks as though they may have implied rather more fiscal degrees of freedom than were actually there, if – critical point – they happened to want to produce a surplus track very like National’s. Gilding the lily isn’t unknown from either side of politics of course.

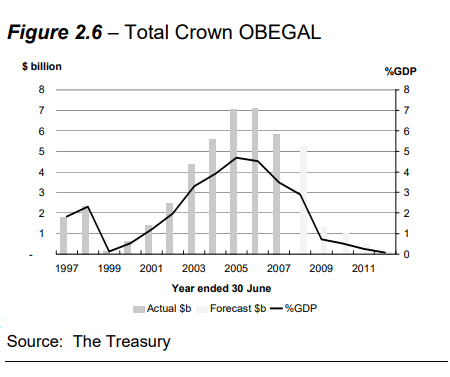

But perhaps the bigger question one might reasonably put to both sides is why the focus on (almost identical) rising surpluses? These are the numbers.

When net core Crown debt is already as low as 9.2 per cent of GDP – not on the measure Treasury, the government and Labour all prefer, but the simple straightforward metric – what is the economic case for material operating surpluses at all? With the output gap around zero and unemployment above the NAIRU, it is not as if the economy is overheating (the other usual case for running surpluses). Even just a balanced budget would slowly further lower the debt to GDP ratios. One could mount quite a reasonable argument for somewhat lower taxes (if you were a party of the right) or somewhat higher targeted spending (if you were a party of the left, campaigning on structural underfunding of various key government spending areas).

When net core Crown debt is already as low as 9.2 per cent of GDP – not on the measure Treasury, the government and Labour all prefer, but the simple straightforward metric – what is the economic case for material operating surpluses at all? With the output gap around zero and unemployment above the NAIRU, it is not as if the economy is overheating (the other usual case for running surpluses). Even just a balanced budget would slowly further lower the debt to GDP ratios. One could mount quite a reasonable argument for somewhat lower taxes (if you were a party of the right) or somewhat higher targeted spending (if you were a party of the left, campaigning on structural underfunding of various key government spending areas).

Labour is promising to spend (and tax – thus the surpluses are the same) more than National. But their commitment (rule 4) was to keep core Crown expenditure “around 30% of GDP”, not “comfortably below 30 per cent”.

28.5 per cent is quite a lot lower than 30 per cent (almost $5 billion in 2020/21 – not cumulatively, as GDP is forecast to to be about $323 billion). And 30 per cent wasn’t described as a ceiling. And in the last two years of the previous Labour government, core Crown spending was 30.6 per cent of GDP (06/07) and 30 per cent of GDP (07/08).

It is a curious spectacle to see a party campaigning on serious structural underfunding of various public services and yet proposing to cut government spending as a share of GDP. It would be difficult to achieve – given the various specific policy promises – but you have to wonder, at least a little, why one would set out to try. We simply aren’t in some highly-indebted extremely vulnerable place.

Finally, the affair of the last 48 hours has revived arguments for some sort of offiical costings unit to be set up, as Labour and Greens have called for (in their Budget Responsibility Rules) and people like the New Zealand Initiative have also apparently favoured. I’m much more sceptical of such proposals, and covered some of the reasons in earlier posts (when the Greens first made a play of this issue last year, and when the Labour/Greens rules were announced). I support the idea of a Fiscal Council – as Labour/Greens have proposed, and as past external reviewers have suggested – although would favour something more macroeconomic focused (ie advice and review functions on monetary policy as well as fiscal policy), but I don’t think the case for a costing unit has been made.

As I noted in one of those earlier posts

On balance, I still think there is a role for something like a (macro oriented) fiscal council in New Zealand, perhaps subsumed within the sort of macroeconomic or monetary and economic council I suggested here (but perhaps that just reflects my macro background). And there is probably a role for better-resourcing select committees. But when it comes to political party proposals, if (and I don’t think the case is open and shut by any means) we are going to spend more public money on the process, I would probably prefer to provide a higher level of funding to parliamentary parties, to enable them to commission any independent evaluations or expertise they found useful, and then have the parties fight it out in the court of public opinion. The big choices societies face mostly aren’t technocratic in nature, and I’m not sure that the differences between whether individual proposals are properly costed or not is that important in the scheme of things (and perhaps less so than previously under MMP, where all promises are provisional, given that absolute parliamentary majorities are very rare). If there are serious doubts about the costings, let the politicians (and the experts each can marshall) contest the matter.

And this particular dispute wasn’t even about the details of the costings of individual policy proposals. It seems to have been more or less sorted out through the cut and thrust of political debate and expert commentary. That feels to me like the way I’d want the system – competing political parties, open democracy – to work. No non-partisan experts can reasonably decree that one set of spending plans is or isn’t feasible or appropriate – much of that is inevitably about politics. There are gaps in our debate – it was notable in the last couple of days that no academics were quoted, even though for example, Victoria University likes to hold itself out as policy-focused, and they even have a professorial chair in public finance – but it isn’t clear that spending more taxpayers’ money to cost political party proposals (according to the particular model of that particular group of technocrats) is a high priority use for scarce fiscal resources.

(I noticed a couple of journalists last night describing me as “dryish right” and thus happy to fling mud at Labour. I’d probably accept “dryish right” broadly speaking, but I’m sufficiently disillusioned with the total failure of this government to deal with housing, and the failures (and, what are in effect, lies) around productivity growth that I’d be more than keen to see a serious credible alternative. As it happens, Labour’s policies around monetary policy and the Reserve Bank – issues of some importance to me, even if not of wide general interest – seem to be heading the right direction. I’m more sceptical as to whether they have more of an effective economic strategy than the government does. Which is by way of saying that I like to think I’m an equal opportunity sceptic – who doesn’t usually vote on economic issues anyway – and if some of this post does identify some challenges for Labour, it isn’t because I’m champing at the bit to see Mr Joyce succeed.)

When net core Crown debt is already as low as 9.2 per cent of GDP – not on the measure Treasury, the government and Labour all prefer, but the simple straightforward metric – what is the economic case for material operating surpluses at all? With the output gap around zero and unemployment above the NAIRU, it is not as if the economy is overheating (the other usual case for running surpluses). Even just a balanced budget would slowly further lower the debt to GDP ratios. One could mount quite a reasonable argument for somewhat lower taxes (if you were a party of the right) or somewhat higher targeted spending (if you were a party of the left, campaigning on structural underfunding of various key government spending areas).

When net core Crown debt is already as low as 9.2 per cent of GDP – not on the measure Treasury, the government and Labour all prefer, but the simple straightforward metric – what is the economic case for material operating surpluses at all? With the output gap around zero and unemployment above the NAIRU, it is not as if the economy is overheating (the other usual case for running surpluses). Even just a balanced budget would slowly further lower the debt to GDP ratios. One could mount quite a reasonable argument for somewhat lower taxes (if you were a party of the right) or somewhat higher targeted spending (if you were a party of the left, campaigning on structural underfunding of various key government spending areas).

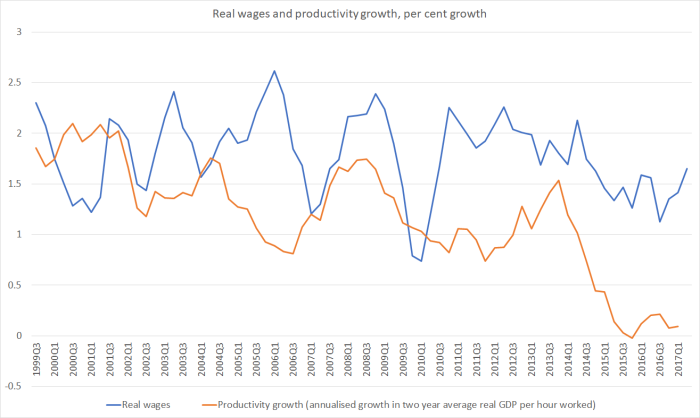

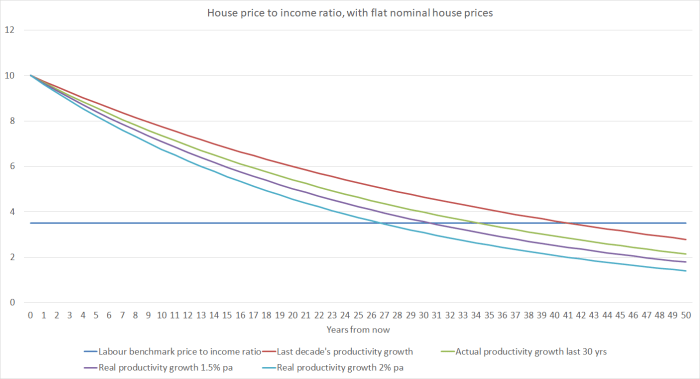

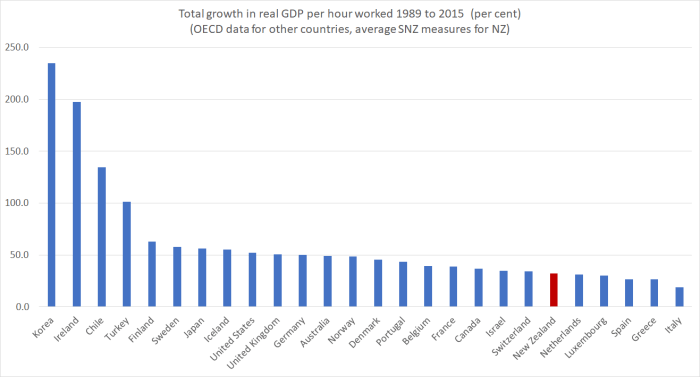

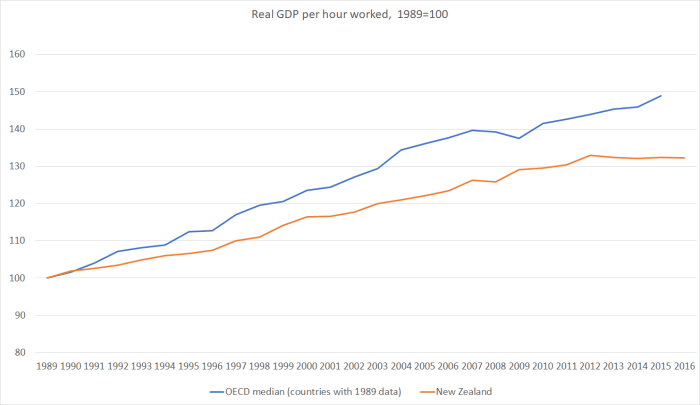

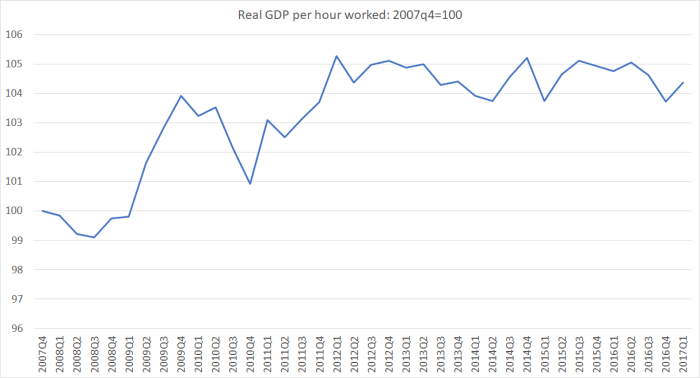

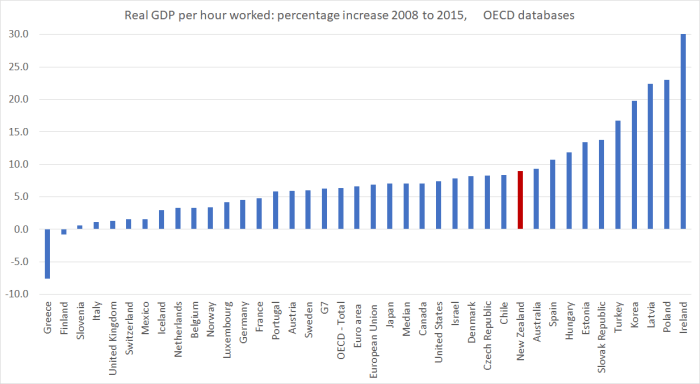

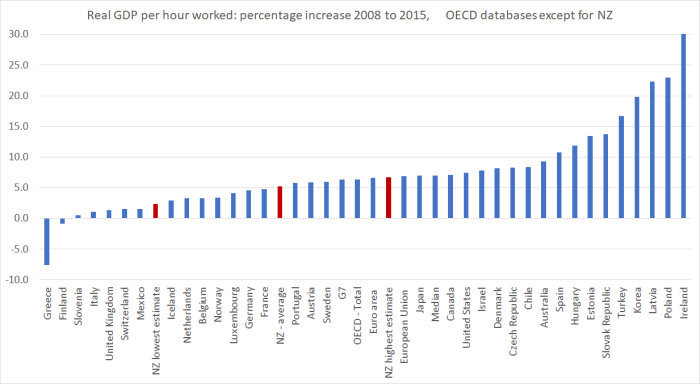

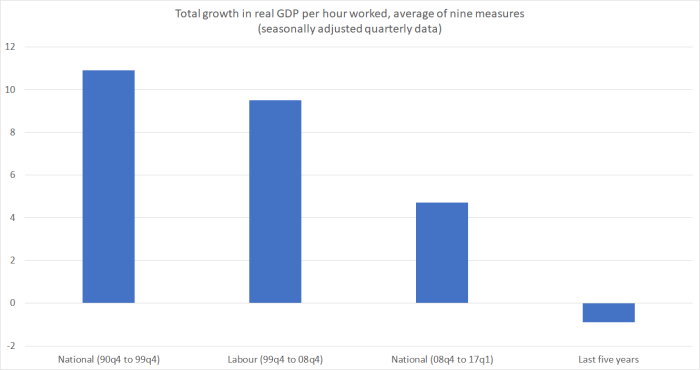

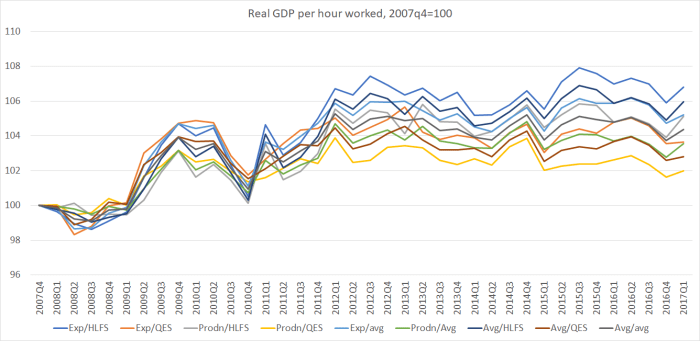

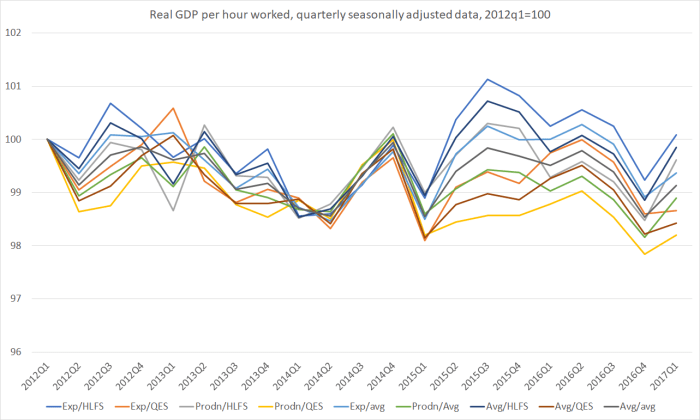

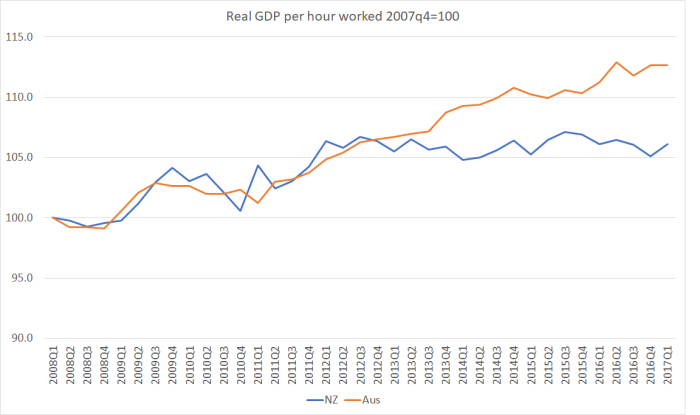

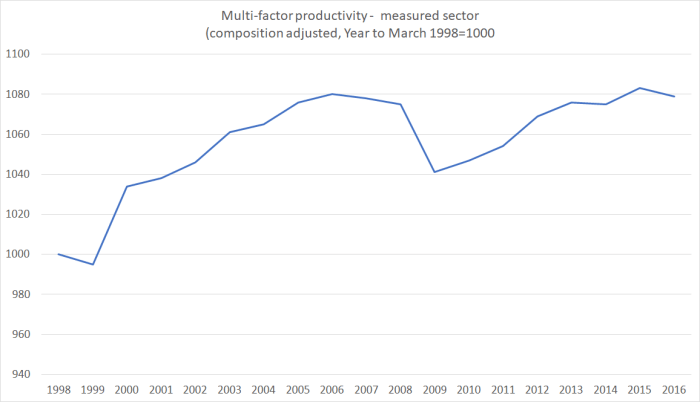

Not only have we had no labour productivity growth for five years, but our near-neighbour Australia – which the government was once willing to talk about catching up to – has gone on generating continuing labour productivity gains. Yes, there has been a productivity growth slowdown in much of the advanced world, dating back to around 2005. But our additional and more recent slowdown – well, dead stop really – looks like something different, and probably directly attributable to New Zealand specific factors. Things New Zealand governments have responsibility for responding to.

Not only have we had no labour productivity growth for five years, but our near-neighbour Australia – which the government was once willing to talk about catching up to – has gone on generating continuing labour productivity gains. Yes, there has been a productivity growth slowdown in much of the advanced world, dating back to around 2005. But our additional and more recent slowdown – well, dead stop really – looks like something different, and probably directly attributable to New Zealand specific factors. Things New Zealand governments have responsibility for responding to.

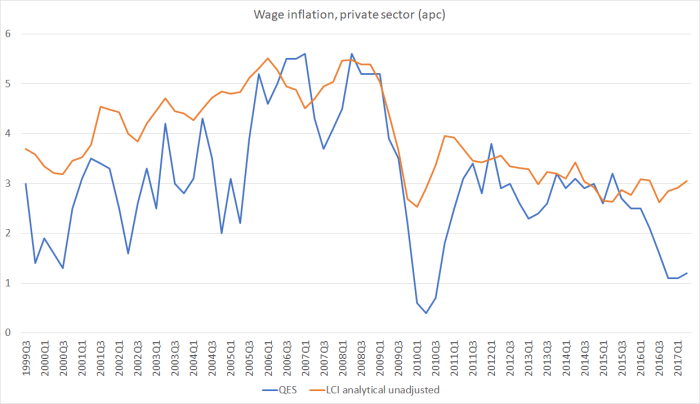

No economic analyst thinks wage inflation is anything like as volatile as the blue line – in fact, wage stickiness, and persistence in wage-setting patterns is one of the features of modern market economies.

No economic analyst thinks wage inflation is anything like as volatile as the blue line – in fact, wage stickiness, and persistence in wage-setting patterns is one of the features of modern market economies.