As part of the current political debate about the relative capability of the two main parties to manage the government finances responsibly, I sometimes see references to the large deficit forecasts that greeted the incoming National government in 2008.

I wrote about this issue a few months ago, in response to some specific claims made by one analyst at the time. I’m reproducing the bulk of that post below (not indented). My bottom line, supported with documentation is

But on best Treasury advice, the then Labour government thought they were leaving an essentially balanced budget [ie the 2008 Budget, their final fiscal policy choices], on top of an already very low debt level, not deficits.

It is certainly true that when the current government took office in November 2008, official fiscal forecasts showed large deficits for many years into the future. But the last fiscal initiatives of the outgoing Labour government had been the 2008 Budget, the parameters for which were set out in the Budget Policy Statement released at the end of 2007.

Throughout much of the previous Labour government’s term of office, a key theme of fiscal policy developments had been the surprising strength in revenue. It was, in many respects, why the fiscal surpluses were so large during those years – Treasury and the government kept being taken by surprise, and Treasury was (prudently) cautious about treating the surprises as permanent. If it was just a series of one-offs, or something cyclical, it wouldn’t have made sense to increase spending or cut taxes in response.

The Treasury gradually revised upwards their assessment of the underlying fiscal position. Unfortunately, they took a particularly optimistic stance by the end of 2007. I can recall the then Prime Minister making much of the fact that Treasury was now assuming that most of the revenue gains would prove permanent (and thus could support some mix of increased spending and lower tax rates) without the risk of dropping back into deficits. I joined Treasury on secondment in mid-2008 and I have seen documents written to the Minister of Finance during early 2008 stating that reassessment. I was under the impression that some had been released, perhaps as part of the pro-active release of 2008 Budget papers, but on checking that link on the Treasury website, I couldn’t see the paper in question.

But the facts of the reassessment aren’t in dispute. Several Treasury staff produced a paper last year on the process of getting back to surplus, including the background to the deficits. Here is what they had to say

Over the period 2005-2008, the Treasury increased its estimates of structural revenues by around 1 percentage point of GDP each year, and by 2008 the Treasury considered most of the operating surplus was “structural”

and

When the tax reductions [along with further spending increases] were announced in Budget 2008, the Treasury was still predicting the operating balance to remain in surplus through the forecast period, albeit at a lower level.

With the benefit of hindsight, the degree to which the surpluses were structural was overestimated. Although the tax reductions announced in 2008 turned out to be well-timed from the perspective of stabilising the economy following the GFC, their permanent nature added to the subsequent structural deficits.

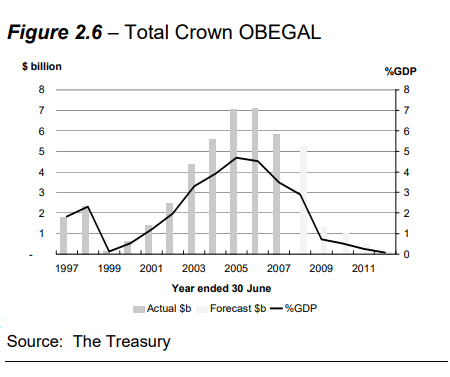

Here is the chart from the 2008 Budget Economic and Fiscal Update.

That document was signed off by the Secretary to the Treasury as representing his best professional assessment of the economic and fiscal outlook, incorporating the effects of announced government policy. In New Zealand – unlike many countries – the forecasts are those of the professional advisers, not those of the Minister of Finance.

On the basis of the economic and fiscal information available to it, the Treasury has used its best professional judgement in supplying the Minister of Finance with this Economic and Fiscal Update. The Update incorporates the fiscal and economic implications both of Government decisions and circumstances as at 9 May 2008 that were communicated to me, and of other economic and fiscal information available to the Treasury in accordance with the provisions of the Public Finance Act 1989.

John Whitehead

Secretary to the Treasury14 May 2008

The projected surpluses by the end of the forecast period were tiny – essentially the budget was projected to be in balance by then. The economic and revenue outlook had worsened over the first few months of 2008, after the broad parameters of the Budget had already been sketched out in the BPS. As we now know, New Zealand was already in recession by May 2008. But on best Treasury advice, the then Labour government thought they were leaving an essentially balanced budget, on top of an already very low debt level, not deficits.

Of course, the government was wrong in that assumption. But, specifically, Treasury was wrong in its best professional advice. Perhaps the government would have run quite expansionary discretionary fiscal policy anyway, even if Treasury had been less optimistic about how permanent the revenue was. They were, after all, behind in the polls, and the PM’s office – didn’t Grant Robertson work there? – would no doubt have been putting a lot of pressure on the Minister of Finance. But that hypothetical didn’t arise. They didn’t have to make such awkward political choices – their own professional advisers told them they could have tax cuts and spending increases, and still keep the budget in (modest) surplus. The Opposition National Party shaped its, more generous, tax cutting promises on much the same sort of Treasury forecasts and estimates. (And a few years earlier, the 2005 election had partly been a bidding war as to how best to spend the surplus – not whether there really was a structural surplus).

It wasn’t Treasury at its finest. It is, perhaps, a reason to be cautious about just how much a fiscal council might add. Would such a body, faced with similar circumstances – a long succession of revisions upwards in revenue – have really reached materially different judgements about the outlook then? Perhaps. We can’t know, but back in 2008 Treasury was using its best professional judgement, and the mistakes were still made.

There is a bit of a tendency afoot to suggest that the current National-led government has done a better job of fiscal management than the previous Labour government did. I’m not really convinced by that story. I’d accept that the previous government might have had an easier job than the current government has – since one inherited modest but growing surpluses, while the other inherited deficits. The current government had some nasty shocks (earthquakes) but also some of the best terms of trade in decades and the weakest wage pressures. But if we expect our politicians to be guided by professional advice in areas like this, the previous government did what most orthodox opinion advised them to, keeping on delivering surpluses and reducing outstanding debt. Probably they should have emphasised tax cuts more than spending increases, but this particular debate is about overall fiscal balances.

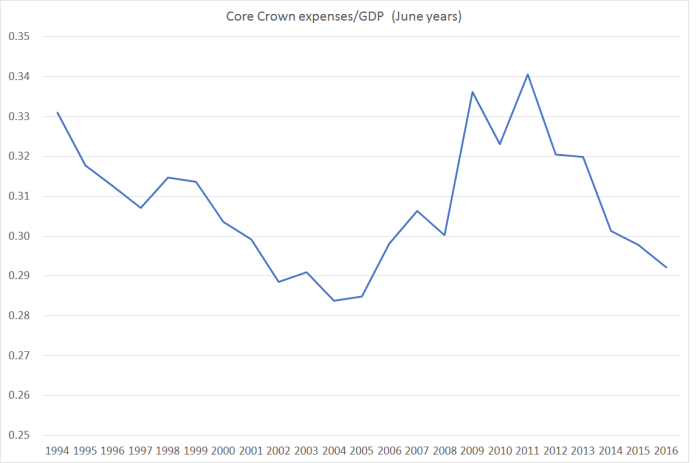

By the end of Labour’s term, government spending as a share of GDP was rising a lot – but then Treasury was telling the government the money was there to spend. And for all the talk of how the new Labour/Greens rules commit a new left-wing government to keep spending at around current National government levels, that level is around the average level that prevailed under the previous Labour government.

There are things I’d criticise about the previous government’s policy. Allowing big structural surpluses to build up, as happened in the first half of the term, set the scene for a big spend-up later (which would have been big tax cuts if National had won in 2005). It is probably better to recognise the limitations of knowledge and typically keep both surpluses and deficits small. But it is easier to say in hindsight than it might have been at the time. And in 1999 [when Labour had come to office], the severe fiscal stresses of 1990/91 were pretty fresh in everyone’s memory.

What is particularly annoying is having to spend $100k on public drainage and development levies on a 3 site subdivision and then being told that house price increases are being caused by property investors who are market followers and not market price setters.

Infrastructure costs should be the responsibility of the government and local council instead of being lumped onto developers who then have to try and make a tiny margin from the sale.

LikeLike

It is even more annoying when there are already 2 existing houses on a cross lease and I have to spend $100k in infrastructure costs to add a third house. Jacinda Ardern is going to be all talk and the only action will be tax water, tax land, tax capital gains for business, tax holiday homes, tax inheritance property, tax shares, tax capital gains on sale of business and also the fart tax.

LikeLike

Perhaps when thinking of what to do with surpluses, instead of tax cuts (Nats) or the alternative increases in social spending (Lab/Green) it would be better to invest in infrastructure? This might be the better way to improve our productivity per capita.

LikeLike

Highlights the dangers of reliance on models that forecast based on a deviation from trend. As you and McDermott point out (regularly) forecasting is hard (https://croakingcassandra.com/2017/07/27/keep-an-eye-on-the-earth-not-the-stars/), the key variables are unknown in real time, and are subject to large revision, undermining what seems like good advice at the time.

Thus a coherent strategy, irrespective of the ‘gaps’ is what is needed, and the spine to stick to your strategy in the face of aberrant data. Obviously the prospect of a close election and apparently lots of spare money made it very difficult in 2008.

LikeLike