Late last year, veteran Australia journalist and author George Megalogenis’s new book Australia’s Second Chance was published. Despite the single economic market, it is often hard to become aware of new Australian books, and not always easy to get hold of them either. Somehow I stumbled on a reference to this book and read it a few weeks ago.

Megalogenis appears to be highly-regarded by the liberal-left in Australia, at least judging from the reviews of his previous book (which was launched by Prime Minister Julia Gillard) that are quoted on the inside cover of this one. Wikipedia says he once was once married to the woman who is now Labour premier of Queensland and, whether because of that or despite it, he appears to have it in for Queensland – not helped, it seems, by the large number of New Zealanders living there.

It is a well-written easily-read book, and for those who don’t know too many details of Australian history since 1788 it is full of interesting facts. It is just a shame that the thesis that shapes the book is almost certainly almost totally wrong.

Megalogenis argues that immigration is what has made Australia rich, and is what will make it richer still in future – if only the naysayers, sceptics, racists etc just get out of the way, and let Australia fulfil its manifest destiny.

You may think I am over-egging his story, but here are some lines from the last page of the book

Australia matters more than most nations because it remains a settlement with potential. Our unique strengths…..come with a burden. The rest of the world expects Australia to succeed, given our small population and resource endowment. Our previous eras of poor performance were punished so severely because the world believed we had let it down. This is the pragmatic argument for openness, because history tells us the alternative is an isolated belittled Australia. A globally minded Australia will continue to thrive, because the world will project its best self on us.

and a page or two earlier, concludes that Australia’s

standard of living depends on the migrant

The test for Australia now, we are told, is “to keep them coming”.

It is really a very odd argument.

As one person I mentioned the book’s thesis to noted, in one sense it is clearly true. Had there been no immigration to Australia since 1788, it seems most unlikely that per capita incomes of Australians would anything like as high as they are today. They aren’t in, say, Botswana or Mongolia.

Then again, as far as we can tell from the historical estimates that are available, Australia’s per capita incomes were the highest in the world in about 1890. Australia has not matched that performance in the 125 years since.

According to Megalogenis, Australia’s success has rested on repeated waves of immigrants, and when the flow slowed times were not typically good for Australians. Mostly, it is a story that seems to reverse cause and effect. Migrants are attracted to economic success and opportunities. In the 19th century it was hugely expensive to immigrate to Australia (or New Zealand) and people did so in large numbers either when someone else paid them to do (assisted migration) or when really good new opportunities (large expected income gains) opened up.

Early European Australia was a penal colony, hugely heavily subsidized by Britain, with few export opportunities and not particularly attractive as a place to relocate to (the total European population in 1820 was 33000). The first big natural resource shock was the discovery of the natural pasturelands in western New South Wales in the 1820s. In 1830, Australian wool accounted for 8 per cent of British wool imports (German states had been the dominant supplier), but by 1850 Australia accounted for more than half of a fast-growing market. The associated income growth markedly boosted both the Australian colonies ability to support themselves, and to support a much larger population at the sort of living standards (or better) they might have been used to at home.

The gold rushes of the 1850s (and sustained high gold production for several subsequent decades) had a similar effect. Whole new incomes could be generated in Australia, supporting high living standards (and associated imports) for a larger population. Immigrants flooded in – as they did later to New Zealand in our gold rushes. Australian exports as a share of GDP rose to around 40 per cent – a level never achieved since. But there is nothing in the economic histories to suggest that the immigrants created the prosperity. Rather, the prosperity made Australia (and especially Victoria) attractive to immigrants. Since the typical immigrants was a single male, content with a pretty rough standard of accommodation – so there weren’t huge initial capital stock requirements – the standard result in Australian economic histories is that the huge inflow of immigrants dampened wages in Australia (relative to a counterfactual in which the gold discoveries had to be exploited only by people already there).

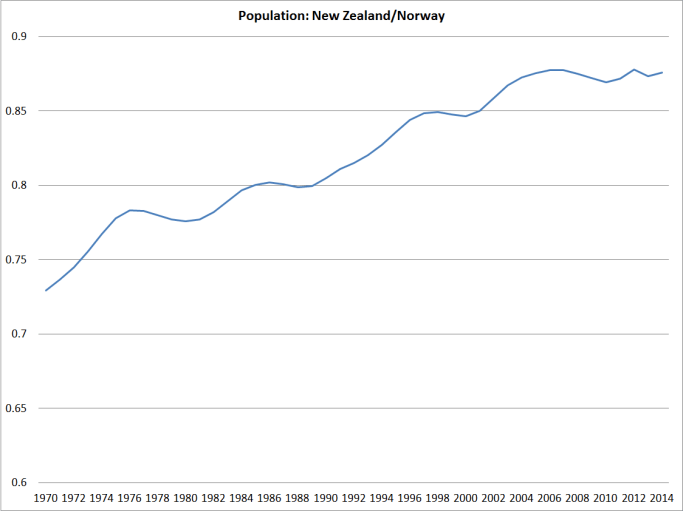

After a final gold rush in Western Australia in the 1890s, there were no great natural resource discoveries in Australia for decades. Agricultural productivity gains continued to lift farm output – and refrigerated shipping and new dairy technologies assisted Australia, although to a lesser extent than New Zealand – but the best land was already taken. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these weren’t great decades for remote Australia. By global standards, it remained a rich and successful country, but no longer at the forefront- indeed, on some of best measures around there wasn’t much per capita growth from 1890 until World War Two. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the rate of population growth wasn’t as rapid – European migrants weren’t quite so keen on coming as they had been (and, as in other settler countries, Asian migration was severely restricted). For the first half of the 20th century, Australia was much like New Zealand – an agricultural exporter, primarily to the United Kingdom. Overall, the two countries generated rather similar living standards – and still had some of the faster rates of population increase anywhere in the advanced world.

Minerals began to come back to prominence in Australia from the 1960s. Australia stopped doing stupid stuff to itself- bans on iron ore exports were lifted, prospecting rights were improved etc – and some combination of new discoveries and new opportunities (the rise of Asia) provided a whole new, increasingly large, income stream for Australia. New foreign income opportunities support higher consumption demands from an existing population, and can sustain a higher population. Mineral exports from Australia had been 1 per cent of total exports in 1951. They were 18 per cent in 1974, 28 per cent in 1989, and 55 per cent in 2009. And exports as a share of GDP were materially higher than they had been in the 1950s and 1960s. New Zealand, of course, has had nothing similar (some argue that there is plenty of mineral potential, but if laws make it difficult or impossible to exploit, it doesn’t matter much whether the enthusiasts are right or wrong).

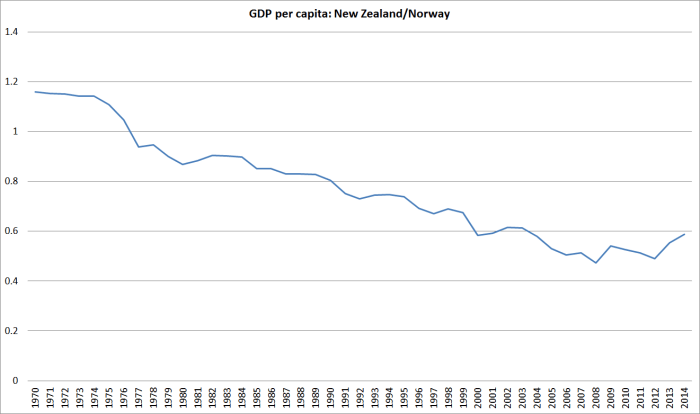

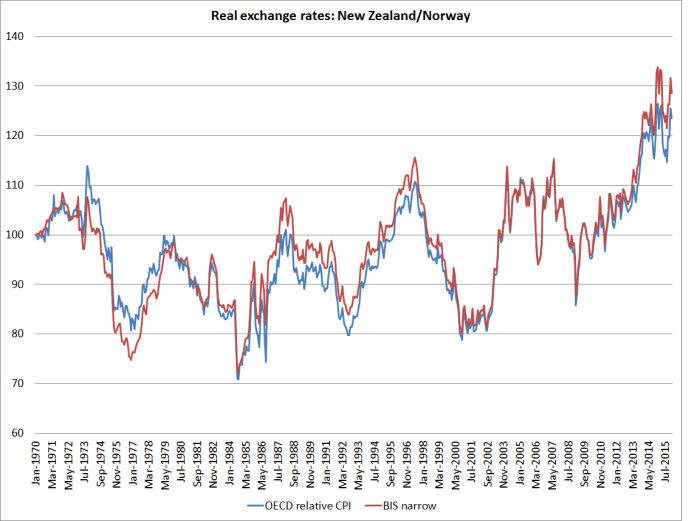

But, contrary to Megalogenis’s thesis, there is just nothing in the data to support the idea that the rapid (immigration-fuelled) population growth has been the basis for strong per capita income growth (over decades). Rather it is the rapid total income growth – particularly associated with mineral developments over the last 40 to 50 years – that has enabled Australia to support pretty good incomes for a growing number of people. Again, we in New Zealand had nothing similar on the income side, and so overall returns (eg GDP per hour worked) available to the growing number of people have continued to languish.

Now, to be clear, this is not some crude story in which physical resources inevitably make a country rich. There are so many counter-examples I’m not going even going to attempt to list them. But new physical resource discoveries, when combined with capable people, and strong institutions, have proved able to generate high per capita incomes for people in places where one might not otherwise have expected such good outcomes. Norway is one example – balancing all three components of that mix.. With more emphasis on the resources than the human capital or institutions, Brunei or Kuwait are other examples (or Equatorial Guinea and Gabon). Australia is closer to the Norwegian end of the story – the same North European combination of people and institutions, that have made for the most prosperous settled societies in history, augmented abundant natural resources (but spread over considerably more people than Norway). Australia doesn’t seem like the sort of location that, natural resources apart, would easily generate top tier incomes – never in its history has it looked like developing seriously internationally competitive manufacturing or services industries based in Australia.

Readers may be skeptical of the story I’ve been telling. But don’t take my word for it. Most of it (and most of the data I’ve quoted) is based on one of my favourite economics books Why Australia Prospered, published in the prestigious Princeton Economic History of the Western World series, and written by the recently-retired leading Australian economic historian Ian McLean. The value of the book is partly that he explicitly considers Australia through a comparative lens, looking at other settler economoies, including New Zealand. I reread it after I’d read Megalogenis, and his story is essentially the one outlined in the previous paragraph. There is no sense, anywhere in the entire book, that anytime in the entire modern history of Australia immigration has been an enabler – allowing Australia to lift its per capita income above what it would otherwise have been.

And what of that bastion of careful economic analysis, the Australian Productivity Commission? They produced a big report 10 years ago, that concluded that there were probably few or no benefits to Australians from modern immigration inflows. And late last year, in response to another government request for a report on immigration, they produced another lengthy draft report. I’d seen a few media reports suggesting that they had reached a positive conclusion on the benefits from immigration, but when I dug into the chapter on the economywide impacts of immigration (from p 263), I found that in their baseline scenario productivity growth and wages were lower in the scenario in which current immigration levels continued than in a scenario without immigration. The differences are very small, and my only point here is that there is little or no support for the sort immigration-boosterism reflected in a book like Megalogenis’s. The Productivity Commission do run an alternative more positive scenario – but essentially it amounts to “what if we just assume that skilled immigration materially boosts productivity growth”. If one assumes gains going into the analysis, one gets gains out the other end.

Over the broad sweep of modern history Australia and New Zealand have had pretty similar approaches to immigration. And they’ve had similar institutions, and similar sorts of capable people. In neither case is there any evidence that continued high rates of immigration have done anything to lift either country’s longer-term economic performance. Rather successful economies successfully absorbed more people at little cost to their own people. The big difference between the two countries in the last 100 years has been the discovery and exploitation of the vast mineral resources in Australia. That has enabled Australia to continue to offer fairly high incomes to a lot more people – including many New Zealanders. Without the new opportunities, products or markets, New Zealand has struggled to cope with its population growth, and continues to drift further behind the rest of the advanced world – putting more people into a place with few natural advantages.

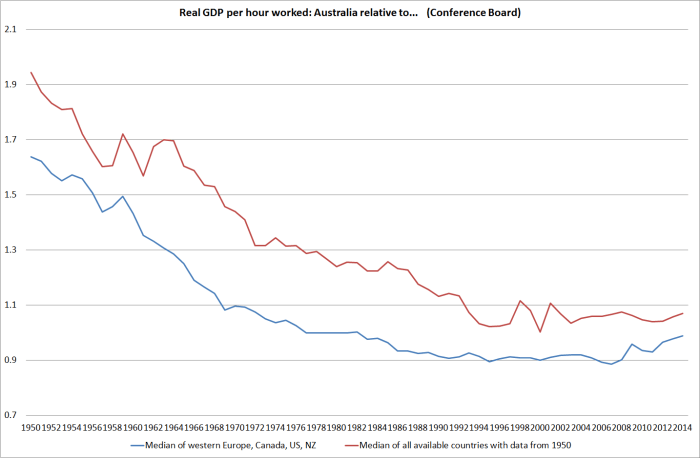

I described Australian incomes as “fairly high”. And yet for all its huge natural resources, Australia’s real GDP per hour worked – while a lot better than New Zealand’s – is no higher than the median of advanced countries. For decades it fell relative to other advanced countries, and even over the last 20 years has done little better than hold its own.

As a topic for another day, might its people also have been better off without such rapid immigration-fuelled population growth?