A couple of months ago a journalist got in touch and asked for some thoughts on New Zealand’s best and worst Ministers of Finance. Eric Frkyberg was working on an article for The Listener, following on from one that magazine ran late last year ranking Prime Ministers. The Ministers of Finance article appears in the issue that turned up in my letterbox at lunchtime. He took views from three historians, a tax policy expert, and me and ended up ranking 10 Ministers of Finance from best (Douglas) to worst (Muldoon).

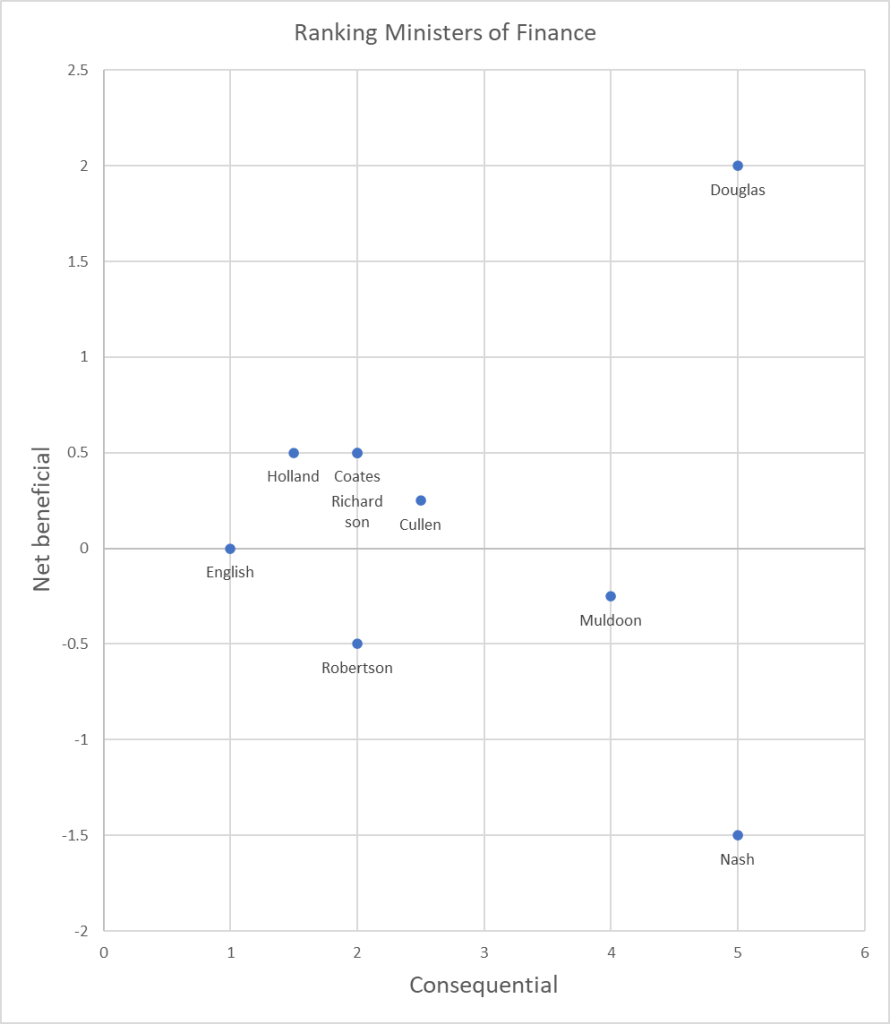

I didn’t actually give Frykberg a simple ranking like that. Instead, I tried to summarise my analysis in this chart

There are other elements one could evaluate these people on (some were more technically able than others, some served in more (or less) propitious times, some will have been nicer people) but I looked at the difference these ministers made, and whether and to what extent I thought those differences had been for good or ill. Nash, for example, was responsible for economic policy for a long time (14 years as Minister of Finance), and the controls-oriented model lasted for decades, but I assess that contribution as deeply net negative (I’m expecting correspondence on this point!). Muldoon was much less consequential because although he was Minister of Finance for much longer than Douglas (say), much of his economic policy (at least the better remembered bits) was swept away pretty quickly, even if they helped trigger what followed.

Anyway, for anyone interested here were the comments I sent Frykberg:

Thoughts on New Zealand Ministers of Finance

May 2025

There have been 29 people who have been Minister of Finance (or Treasurer, or Colonial Treasurer) since 1900, seven of whom were Prime Minister at the same time.

14 of them served for a significant period of time (more than one full parliamentary term)

Of the others, a couple are worth consideration as among the better Ministers of Finance, people who made a discernible difference even though both served for only about three years (Gordon Coates and Ruth Richardson).

Of the earlier list, I’d quickly knock out of consideration Allen, Lake and Birch. Each seems to have been a fairly safe pairs of hands, without contributing a great deal that was distinctively constructive as Minister of Finance. [A former Treasury official recently passed on anecdote re Lake – who had had health problems for much of his term – that Treasury knew not to expect that he’d read anything longer than a page or two.]

And I’d also knock out both Seddon and Ward (despite their long terms), probably mainly because until the Great Depression macroeconomic management really wasn’t a thing in New Zealand, but also because of Ward’s questionable personal business record/bankruptcy and his ill-starred return in 1928.

That leaves a reduced list of:

Downie Stewart[1] is also worth a mention, mostly because he was the last Minister of Finance to resign on an issue of policy principle (he opposed the exchange rate devaluation in 1933 and resigned). I think his policy position on that issue was wrong, but I admire a politician willing to pay the price.

How to think about each of these nine?

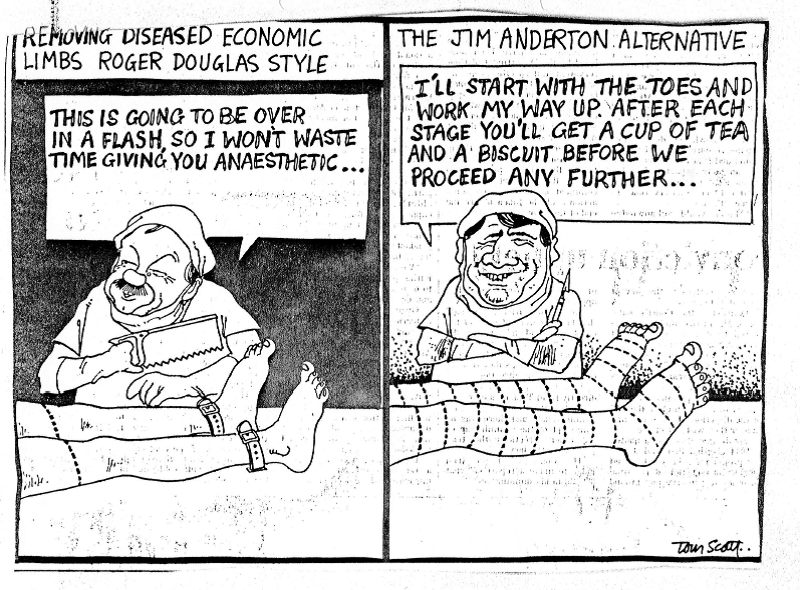

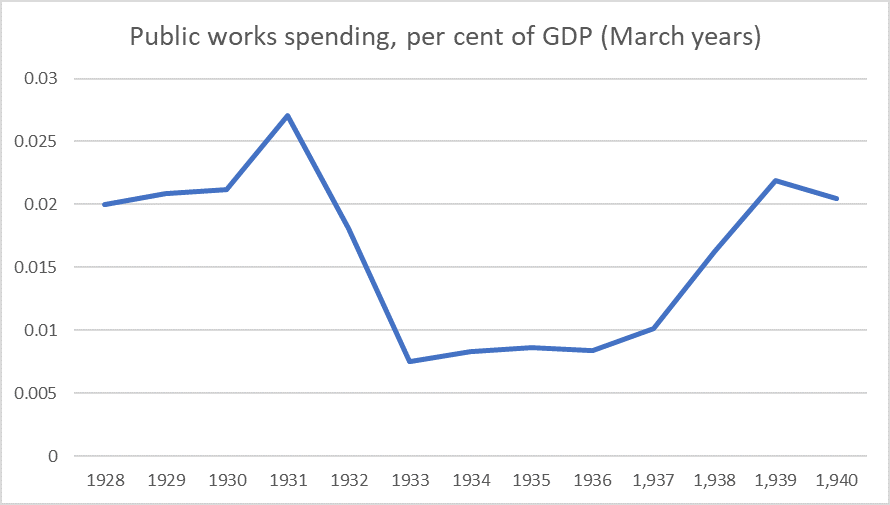

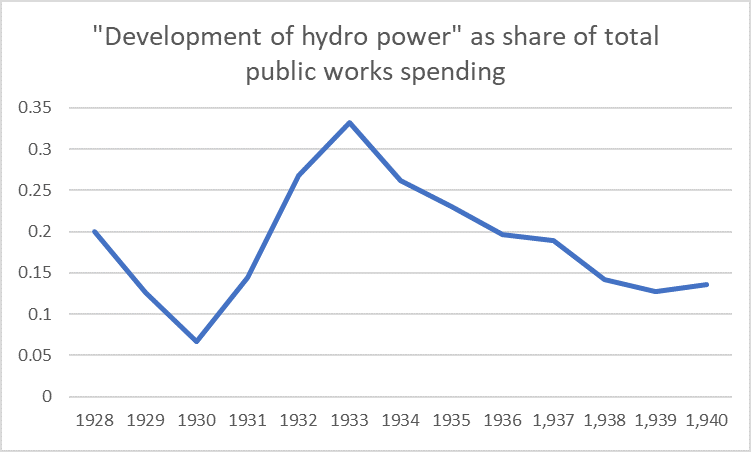

Coates won the battle to depreciate the NZ pound (such as it was) in early 1933, which helped turn the tide of the Great Depression. On the other hand, he was also responsible for the deliberate default on the NZ government’s domestic public debt. He was responsible for the establishment of an independent Reserve Bank in 1934 (and our first coinage in 1933). He was, to some extent, fortunate in his timing – the worst of the Depression in the UK for example had already passed by the time he took office – and the pressure to cut spending (because of limited access to forex, whether from net exports or borrowing) had eased. Work on a central bank had already been underway before he took office, but he nonetheless made it happen. By the time he went out of office New Zealand had substantially recovered from the Depression.

Nash was Minister of Finance for 14 years in succession (albeit for a couple of years he was minister resident in Washington) which warrants consideration. He deserves most credit perhaps for his fiscal stewardship of WW2 and the substantial reduction in NZ government outstanding external debt through that period. On the other hand, his Reserve Bank reforms were a clear step backwards (putting the Bank under the thumb of government, and macroeconomic policy generally was run far too loosely in the early years, running into a foreign exchange crisis in late 1938 and what would have been default on sovereign foreign debt in 1939 if the approach of the war had not made the UK willing to intervene to enable maturing debt to be rolled over. Moreover, the entire turn inwards (import licensing etc) occurred on his watch, and post war the government was far too slow to (a) liberalise, and b) keep inflationary pressures in check. If there are positive enduring legacies of the 1st Labour govt it isn’t obvious things Nash was primarily responsible for are among them.

Holland isn’t primarily remembered as a Minister of Finance, but served as both PM and Minister of Finance from 1949 to 1954. He was the first Minister of Finance after the 1st Labour govt, and made a number of useful steps (seeking to unwind import licensing, enabling tenants to buy state houses, removing the ability of the Minister of Finance to direct the Reserve Bank, the revival of monetary policy as a countercyclical tool, seeking to reintroduce competition in domestic aviation, ending rationing, introducing the annual Economic Survey to accompany the Budget).

Muldoon is a polarising figure. Perhaps his biggest misfortune was to be Minister of Finance spanning almost entirely the period of very decline in New Zealand’s terms of trade (almost entirely outside NZ’s control). A focus on the 1982-84 price and wage freeze, the undelivered 1984 Budget and the 1984 devaluation would lead to a very low score, and one could add Think Big to that mix especially with the benefit of hindsight[2]. The inflation record increasingly stood out (to our discredit) relative to peer countries abroad.

On the other hand, he left office with net govt debt only about a third of GDP (not much higher than now), had managed the late 60s slump in the terms of trade and painful (IMF- supported adjustment) as well as anyone was likely to have at the time. And as Minister of Finance he also presided over significant, if fitful, financial sector liberalisation (right almost to the end) and in his combined PM/MOF role enabled CER, plans to reduce the importance of import licensing, road transport and shopping hours liberalisation, corporatising rail, and so on.

It is a very mixed record. And he ends up not as consequential as either Nash or Douglas because little that he did really lasted long (good and bad both subsumed in the Douglas/Lange “revolution”).

Douglas was Minister of Finance for a little under 4.5 years, but it was an enormously consequential period (including that most of what was done then lives on in one form or another) and the dominant view among economists would probably be that those changes – in law and ethos – reestablished macroeconomic stability (fiscal and monetary) and contributed to a sustained improvement in our productivity performance (at least relative to the counterfactual). He remains enormously controversial – perhaps an embarrassment to his own (then) party – and he was part of a team of ministers, but specifics one could point to include the Public Finance Act, the Reserve Bank Act (although legislated under his successor), an overhauled and much more efficient tax system, the corporatisation and privatisation of government trading entities, the removal of interest rate, exchange rate, and exchange control regulations etc.

Richardson was Minister of Finance for only three years, and arguably the thing she is most remembered for (the Fiscal Responsibility Act) was achieved only after she was sacked as Minister of Finance and had left Cabinet. Notwithstanding the headlines and historical memory around the Dec 1990 fiscal package and the 1991 “Mother of All Budgets”, much of the necessary structural fiscal adjustment had already been done by Douglas/Caygill (government was running a significant primary surplus by the year to March 1991). In that sense, she consolidated and extended work already under way. Deserves credit for greatly accelerating the increase in the NZS eligibility age (a process initiated by Caygill). Arguably the biggest economic policy reforms of that government’s term was the Employment Contracts Act, but it was Bill Birch’s legislation not Richardson’s.

Cullen. In a blog post on Cullen’s memoir I wrote

“On the front cover of the book, Helen Clark describes Cullen as “one of our greatest finance ministers”. There aren’t that many (relatively long-serving ones) to choose from but I’d hesitate to endorse the accolade. Running down the public debt was an achievement but (a) demographics, (b) a prolonged, but productivity-lite, boom, and (c) the terms of trade ran strongly in his favour, and the dam burst in the final three years of his term. I guess he has monuments to his name – Kiwisaver and the NZSF (“Cullen fund”) – but then so does Bill Birch from his time as Minister of Energy, and the best evidence to date is that Kiwisaver has not changed national savings rates, and it isn’t clear what useful function the big taxpayer-owned hedge fund has accomplished. Meanwhile Cullen – and Clark herself of course – bequeathed to the next government (who in turn bequeathed it to this one), the twin economic failures: house prices and productivity (the latter shorthand for all the opportunities foregone, especially for those nearer the bottom of the income distribution).”

15 years on Kiwisaver and NZSF have endured so Cullen probably deserves marks for consequentiality. But not much had been changed for the better. Note that he shouldn’t really be blamed either for the deficits that emerged as he left office – on his last (2008) Budget Treasury’s best professional forecasts/estimates were that the budget would remain (narrowly) in surplus. They were wrong, but that wasn’t Cullen’s fault. He thought he was going to leave a balanced budget.

English was Minister of Finance for eight years. There is little to show for that time. The government’s finances took a major hit with the Christchurch earthquakes but it still took a long time for the government to take the steps that would return the budget to balance. There were few, if any, significant and positive economic reforms initiated and the twin legacies – house prices and productivity – I noted for Cullen above were also unaddressed on English’s watch. He enabled a serious decline in the quality of The Treasury. If one were looking for things to credit, the 2010 tax switch is probably worth a favourable note but it involved an overall increase in taxes on business (at a time when business income tax rates were generally being lowered globally).

Robertson was Minister of Finance only 18 months ago and so one could argue we are too close to evaluate him fairly. There isn’t much to his credit (positives might include establishing a Reserve Bank MPC rather than a single decisionmaker – although his claim to credit is marred by going along with a model that initially banned experts from serving and still in effect bars them from speaking – the new deposit insurance scheme, and the critical early couple of months of Covid). On the other hand, he inherited a structural budget surplus and bequeathed a large structural deficit (after the Covid effects had already passed through), made few/no useful structural reforms and displayed little real interest in productivity, he reappointed an RB Governor who had performed really badly (financial losses, inflation, personal style) and had failed to do much to reverse the decline in The Treasury. So both institutions and macroeconomic outcomes worsened materially on his watch. A moderately high score for consequentiality relates to (a) Covid, and b) the difficult legacy left.

One last candidate

In this exercise I focused only on the period since Seddon/Ward. If one were to take the entire sweep of post-1840 New Zealand history one could argue this overlooks a prime contender for best and/or most consequential Minister of Finance

Vogel served four stints as Minister of Finance (Colonial Treasurer) totalling about nine years. He was, arguably, the first champion in a succession of “big New Zealand” politicians, and was the author of the first “Think Big” economic strategy – borrowing on a large scale in London to facilitate immigration and railways development[3]. He’d easily be in top 3 for consequentiality, although no doubt views would differ widely on how appropriate or beneficial the economic strategy was.

In summary

Here’s a chart [see above], trying to summarise how I see these ministers on the twin dimensions of consequentiality and net benefit (the latter can be positive or negative).

It is worth bearing in mind that all of them were creatures of their time (Douglas in 1935 and Nash in 1984 would no doubt have done things differently than in their own time; Muldoon might have struggled to feature at all had he just been Minister from say 1960 to 72).

[1] Disclosure of interest here: I’m related to Holland and my wife and kids to Downie Stewart.

[2] Nonetheless, I recall Graeme Wheeler – who was in the energy section of Treasury at the time – telling us that contemporary Treasury opinion had been pretty divided on the merits of Think Big.

[3] I wrote about him here A former Prime Minister and Minister of Finance on immigration policy | croaking cassandra