In my post last week on ANZ’s note on the balance of payments, I included this chart from the latest IMF WEO (numbers finalised late last month). On the IMF’s read we had the most overheated advanced economy this year taken as a whole.

ANZ themselves followed up with this chart

(As a reminder, the output gap is the difference between actual GDP in a period and the analyst’s estimate of potential GDP – loosely, the level of GDP in a particular period consistent with avoiding imbalances emerging (be it inflation pressures or current account ones). Since potential GDP is unobservable (and actual GDP is forecast and subject to revisions), “the output gap” isn’t directly observable, even well after the event. But the numbers that forecasters put in their tables are still useful, because they tell us how those forecasters, and the organisations that employ them, are seeing capacity pressures in the economy. They might prove to be right, or be proved wrong, but it is the view they are signing on to. And the great thing about a collection of national forecasts like those in the IMF WEO is that it is a single organisation with a single broad methodology at a single point in time.)

When there is a large output gap (positive or negative) it is reasonable to start asking questions about the performance of the central bank. The reason we set up central banks with discretionary monetary policy is to reduce the extent or duration of those imbalances, while keeping inflation in check. Sometimes there can be tensions between those goals but in the presence of demand surprises one tends to see both positive (negative) output gaps and high or rising (falling) core inflation at much the same times. A large output gap and inflation well away from target in such circumstances is a mark that the central bank has not done its monetary policy job well.

But it was all very well to spot that the IMF now believed the New Zealand economy to have been more overstretched than any other advanced economy for which they run these numbers – not that the IMF itself made this point in their recent Article IV report on New Zealand – but I was curious to see how their own thinking had evolved. Was this a new take on New Zealand’s relative position or not? And so I dug out the IMF output gap estimates/forecasts back to those published in April 2021.

And from here on I’m mostly going to concentrate, and illustrate, only the 10 countries/regions for which there is an output gap estimate and where there is a central bank with its own monetary policy. Most of those European countries in the earlier charts are subsumed in the euro-area estimate.

It is also important to mention that IMF projections are done on a current policy basis, so each of these charts is showing how the Fund thought economies would behave if the policy rate was left as it was at the point the forecasts were finalised.

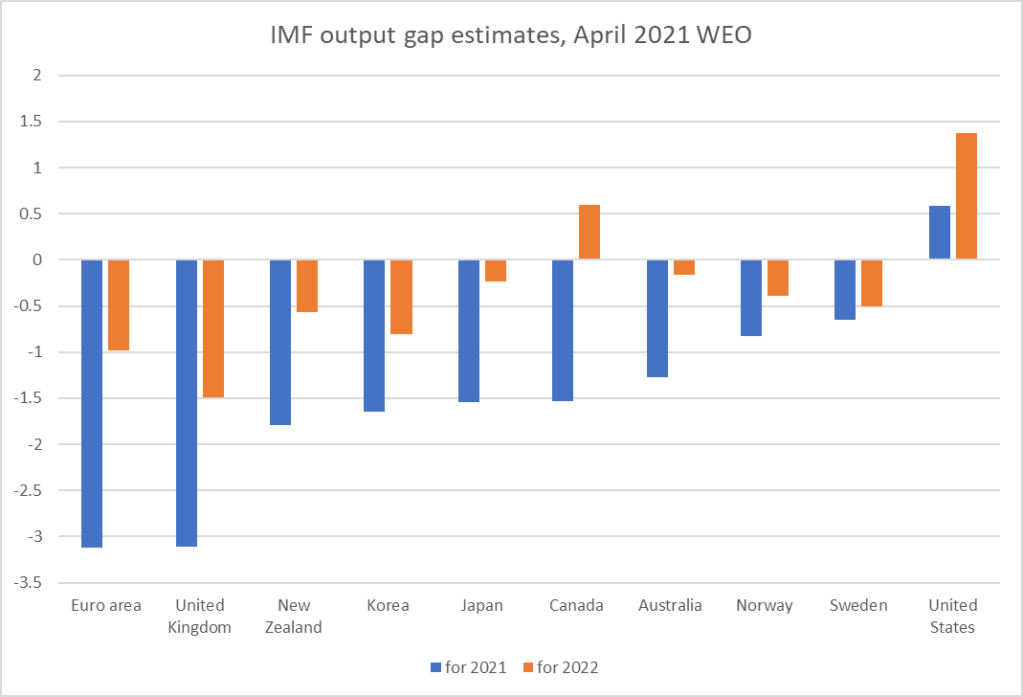

Here is what the output gap estimates as at April 2021 looked like

New Zealand didn’t stand out, and if anything the Fund thought our output gaps for both 2021 and 2022 would be more negative than for most other countries. Recall that as this time, our domestic economy was recovering quite strongly, but perhaps the Fund was influenced by the likelihood of prolonged border closure (recalling that New Zealand has been a much bigger exporter than importer of both tourism and export education services). Locally, the Reserve Bank estimated in both its February and May 2021 MPSs that we’d have a negative output gap in 2021, but they expected – using endogenous policy rate forecasts – a positive output gap in 2022.

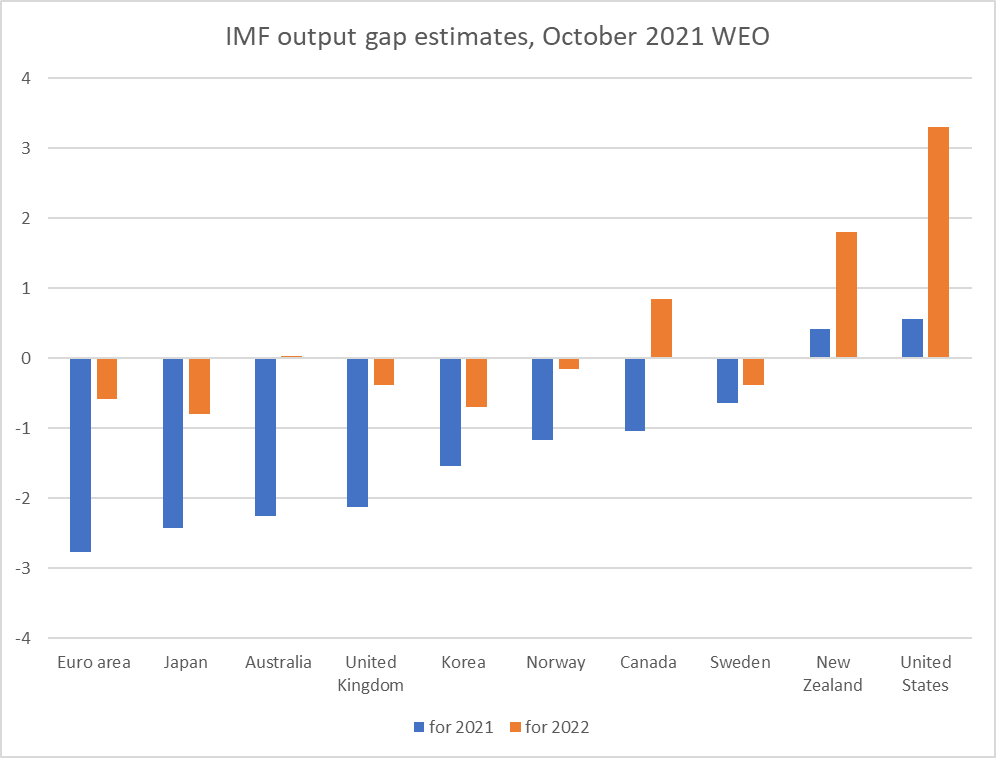

By the next WEO, the IMF’s view on New Zealand had changed quite sharply

By then – still amid the extended lockdown of Auckland – New Zealand was standing out as having, in both years, the second largest positive output gaps, behind only the US. (The Reserve Bank’s forecasts for New Zealand – which included some policy adjustment effect on the 2022 numbers – were pretty similar.)

I’m not going to show you the individual charts for the April and October 2022 and April 2023 WEOs because…..in all of them New Zealand is shown as having the largest positive output gap in both years (eg by 2022 forecasts for 2022 and 2023) of any of those any of these central banks were facing. Here is the October 2023 version though.

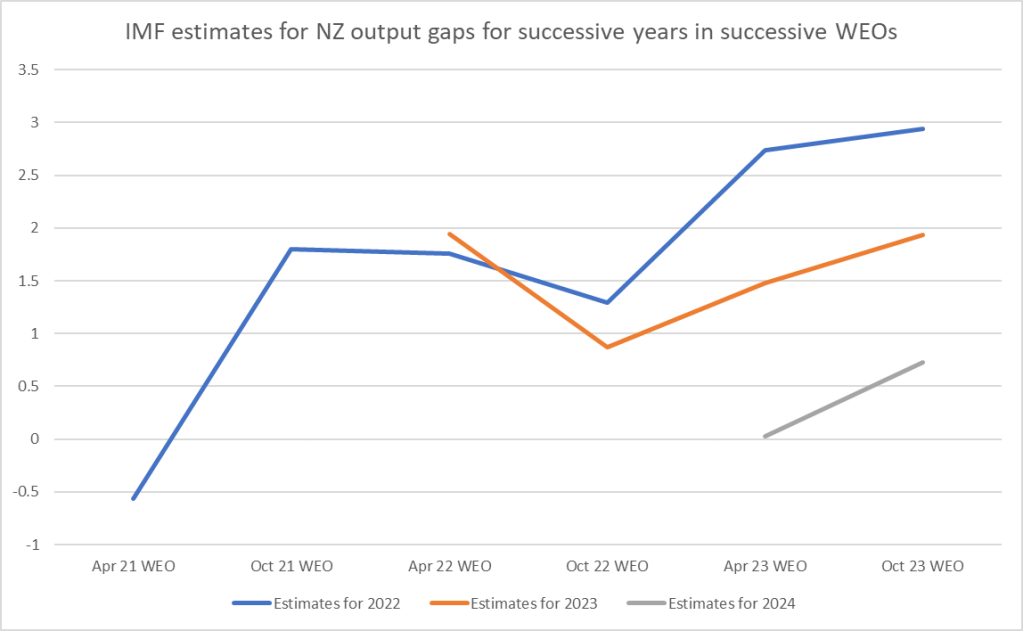

Here is how their New Zealand forecasts/estimates have evolved

Recall that all of these numbers were done on policy rates as they stood at the time (0.25 per cent in April 2021, 5.5 per cent in the latest forecasts), and yet the estimates of 2022’s output gap have just kept being revised up and there is no sign yet of their estimates for 2023 (or the few observations for 2024) being revised down, as one should have hoped.

So on the IMF’s telling all last year and this not only have we had consistently the most overheated economy in this set of advanced countries, but if anything the extent of the overheating has been revised upwards. If that was even close to being an accurate description of how things are it would add to the case (already evident in core inflation itself) that the Reserve Bank MPC has done a poor job, both absolutely and relative to its advanced country peers.

Here is the Reserve Bank’s own take over successive MPSs since the start of 2021.

It is telling that as early as February 2021 – eight months before they actually started raising the OCR – the Reserve Bank thought the economy would be stretched beyond capacity (which is basically what the output gap is) for each of the following three years.

It is also worth noting how stable their estimates for 2022 have been for a couple of years now, even as it passed from prospect to history. It isn’t a perspective you hear about from the MPC – a severely overstretched economy, and stretched to a magnitude that (on IMF reckoning) hadn’t been seen in any of these other advanced countries. As time has gone on they’ve increasingly revised up their view of how stretched things were in 2021 as well. None of these advanced economies are thought to have had 2 per cent positive output gaps two years in succession. But New Zealand did.

When we come to 2023 there is a big difference between the IMF view and the Reserve Bank view. Believe the IMF and 2023 as a whole still looks pretty bad – yet another 2 per cent plus output gap. But if you believe the Reserve Bank, for this year as a whole the output gap will have been almost zero (0.2 per cent on average), before the output gap goes deeply negative next year. The IMF of course does not agree with the Reserve Bank – there is a radical difference between the Fund’s view (0.7 per cent positive) and the negative output gap of 1.7 per cent of GDP the Reserve Bank expects for next year. If we simply slotted the Reserve Bank’s number into the IMF table/chart, the New Zealand output gap next year would be more deeply negative than those for any of the other advanced economies.

Now you might be thinking, “well, even if they got things wrong initially, hasn’t the Reserve Bank done a lot since?”

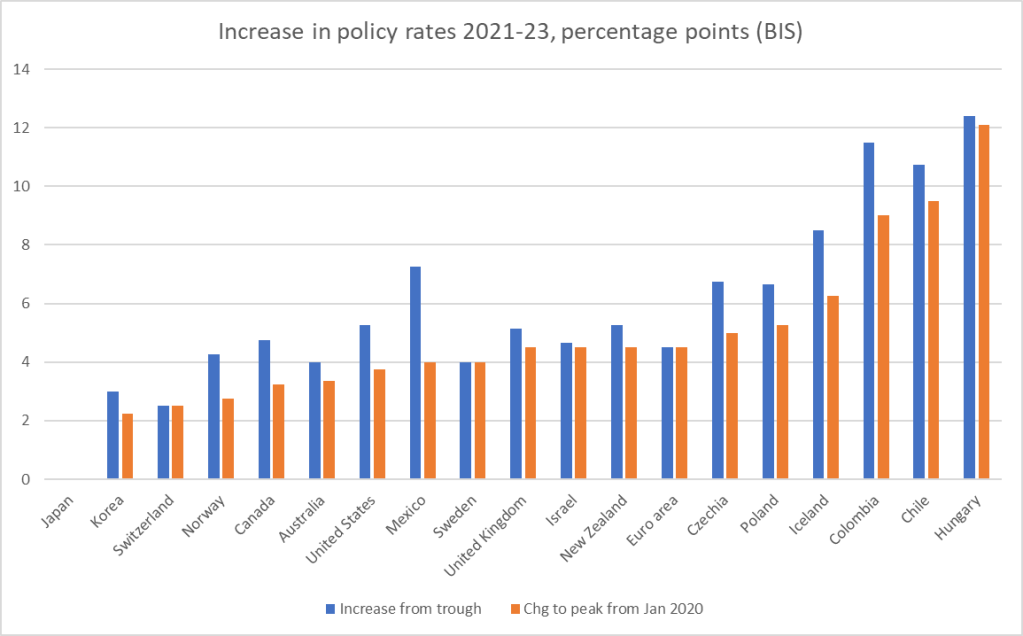

This chart shows the policy rate adjustments for all the OECD central banks in the BIS policy rates database, shown both relative to the Covid trough and relative to the immediately pre-Covid starting level in January 2020

Unfortunately we do not have IMF output gap estimates for the six countries furthest to the right on this chart, but even if we set them to one side there is nothing very startling about the extent of the Reserve Bank’s policy rate adjustment, even though – on its own numbers and those of the IMF – it was dealing with a really severely overheated economy, both in absolute terms and relative to advanced country peers. For what it is worth, in past cycles New Zealand has typically had policy rates quite a bit higher at peak than places like the US, Canada, and the UK. Thus far – and despite the severely stretched economy – that hasn’t proved to be the case this time.

Looking ahead, it is an open question whether the Reserve Bank’s (now-dated) August outlook will prove nearer to the mark than the IMF’s. We (and they) must hope so, given that inflation is still such a long way now from the 2 per cent target midpoint the MPC is supposed to be focused on. This week’s labour market data may provide some helpful hints. If we took the unemployment rate as it has been over the last couple of years and added in the consensus estimate for the September quarter (out on Wednesday) you’d certainly take the view that capacity pressures in 2023 will have been less than those in 2022. But even the IMF numbers tell such a story. But is it plausible to suppose that for 2023 as a whole the output gap will have closed almost completely as the Reserve Bank reckons? It seems a stretch to me, since no one much believes that an unemployment rate averaging below 4 per cent – which now seems almost certain for 2023 – is anywhere near a New Zealand NAIRU. We’ll see, and we’ll see what the Reserve Bank has to say later this month, before the MPC shuts down for their long summer holidays.

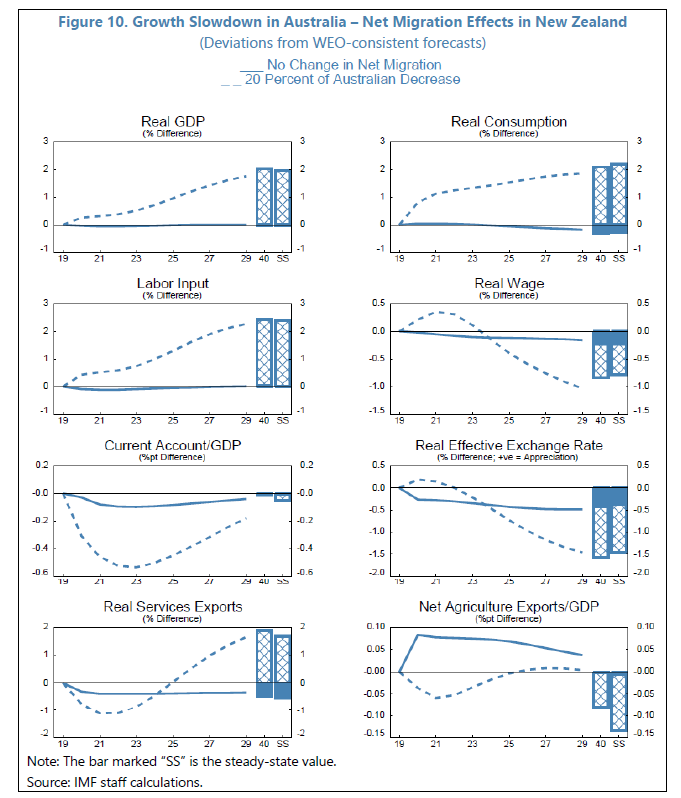

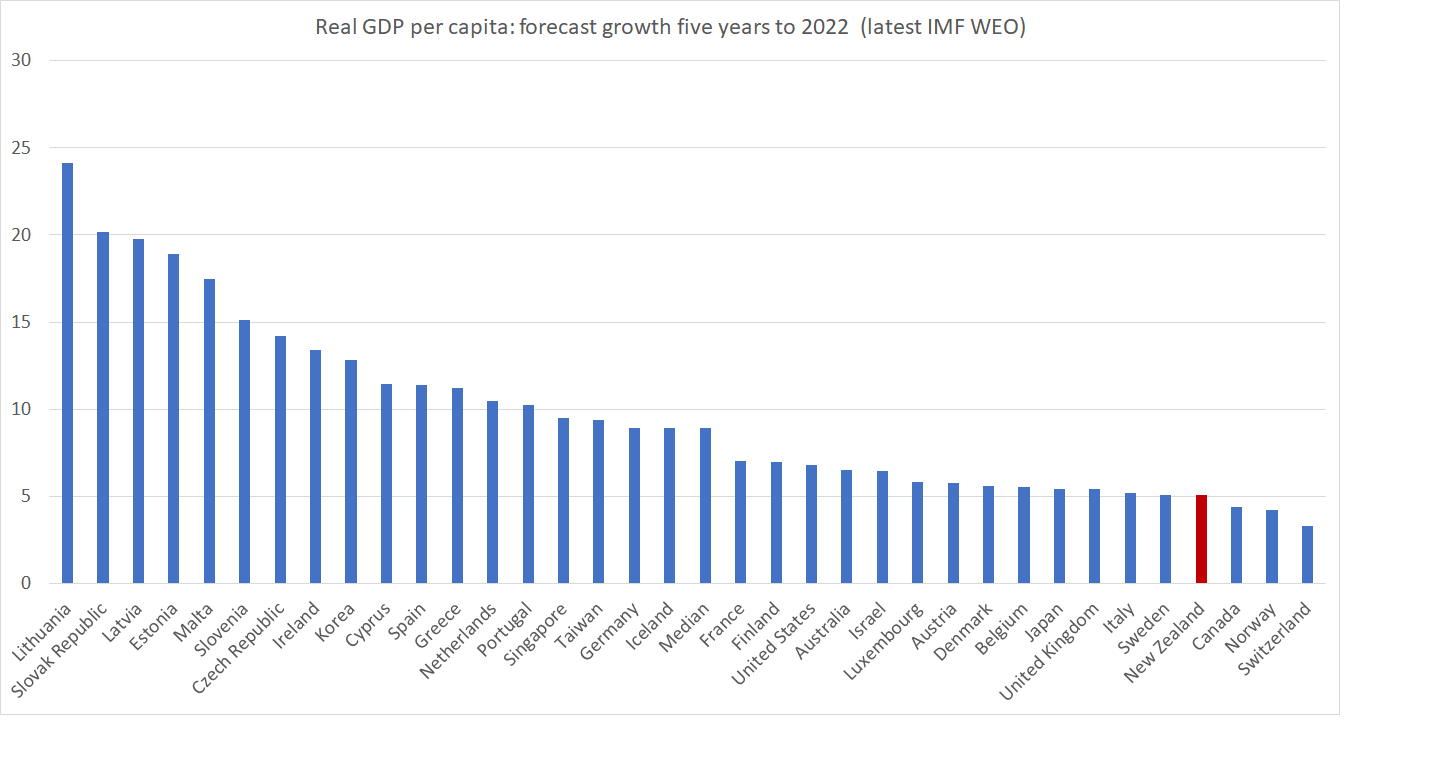

Finally, it is worth reflecting a little on quite why New Zealand might have had the most overstretched economy in the advanced world in 2022 and 2023. There were some positive factors, eg we weren’t in the Ukrainian war zone or directly affected by gas supply/price issues. But, on the other hand, despite the reopening of our borders, net services exports have remained pretty weak, acting as a drag on demand.

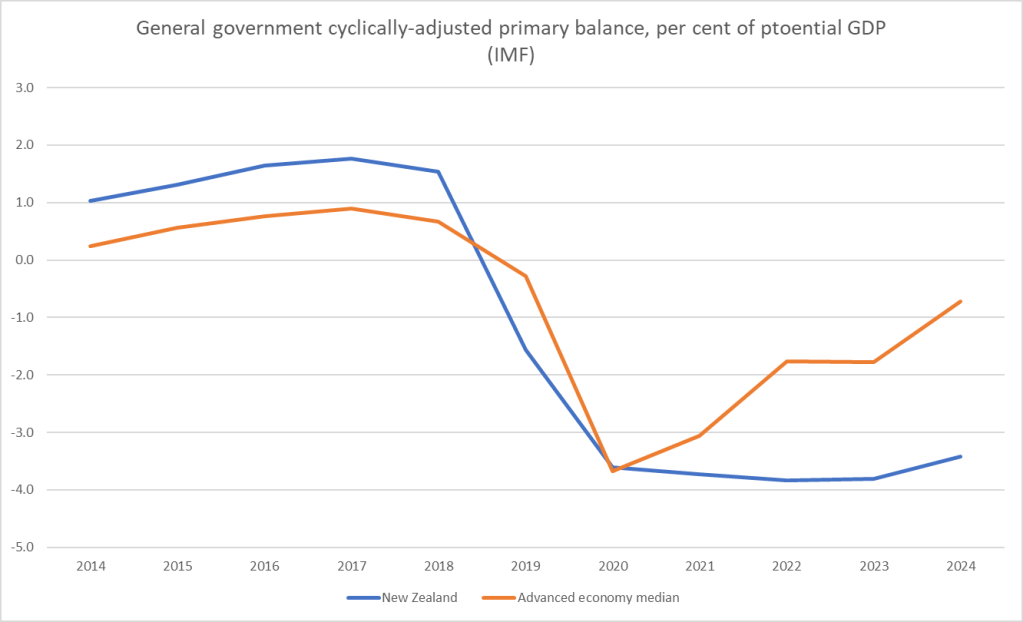

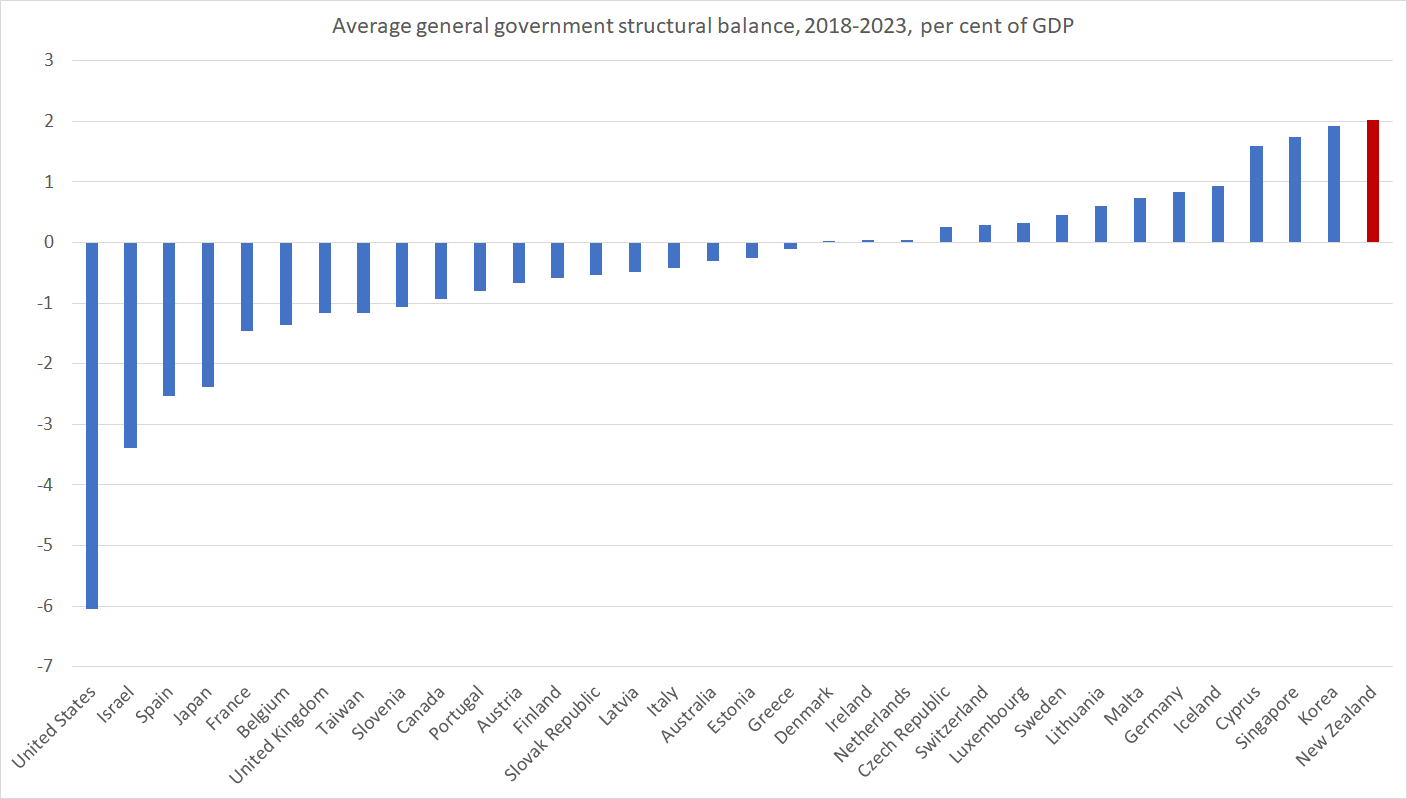

A good candidate hypothesis for what went on here was fiscal policy. I’ve pointed previously how unusual discretionary fiscal policy has been here in the last couple of years. Most countries ran quite big deficits in 2020 in particular around providing Covid support. We did too. But the median advanced economy also then saw deficits closing quite a lot (the IMF median projection for next year is getting close to primary balance).

By contrast, the (now) outgoing government here chose to run to materially expansionary budgets in both 2022 and 2023. That compounded the challenges facing the Reserve Bank’s MPC, since even if the direction of policy was reasonably signalled, the magnitudes were not. Expansionary fiscal policy puts more pressure on demand (showing up in output gaps and current account deficits) and inflation, which proved very unhelpful when the Bank itself was still realising how badly it had earlier misread underlying pressures anyway.

One might have more sympathy with the Reserve Bank had they beeen upfront about these pressures. But this year in particular they have repeatedly sought to minimise the role of fiscal pressures and fiscal surprises, to the point of attempting to reinvent macroeconomics in apparent service of the political interests of themselves and their masters. But that is topic for another post.

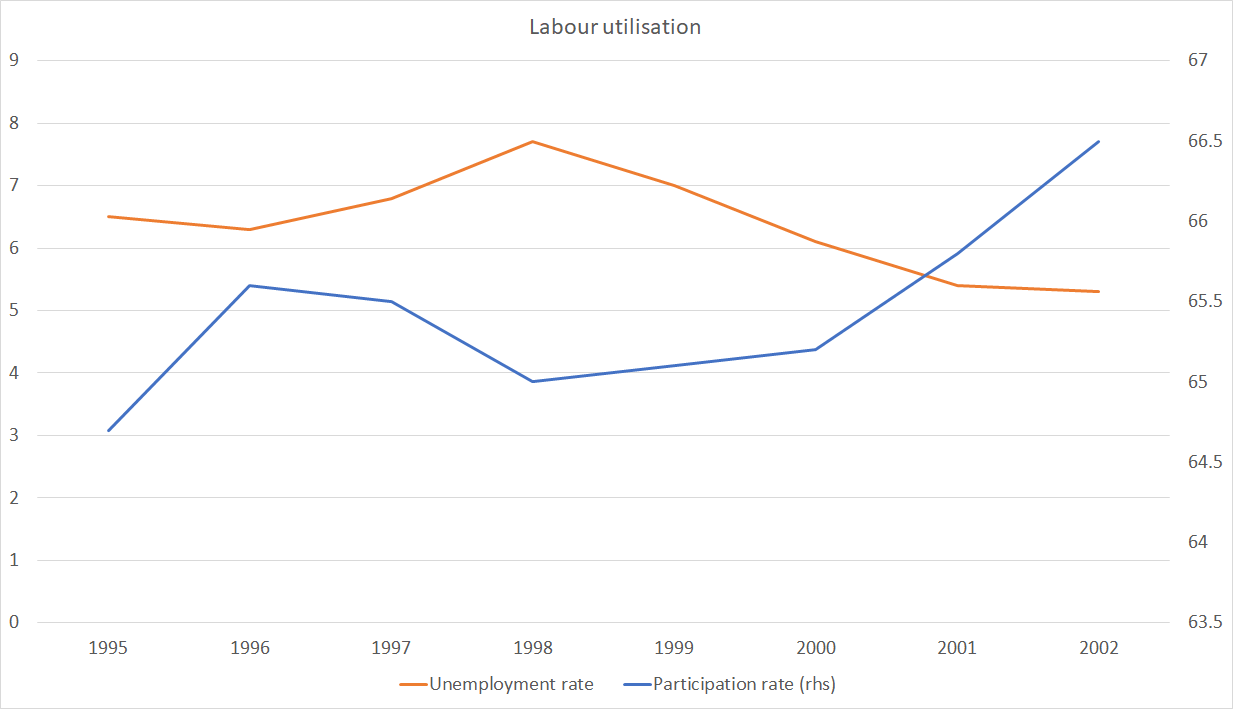

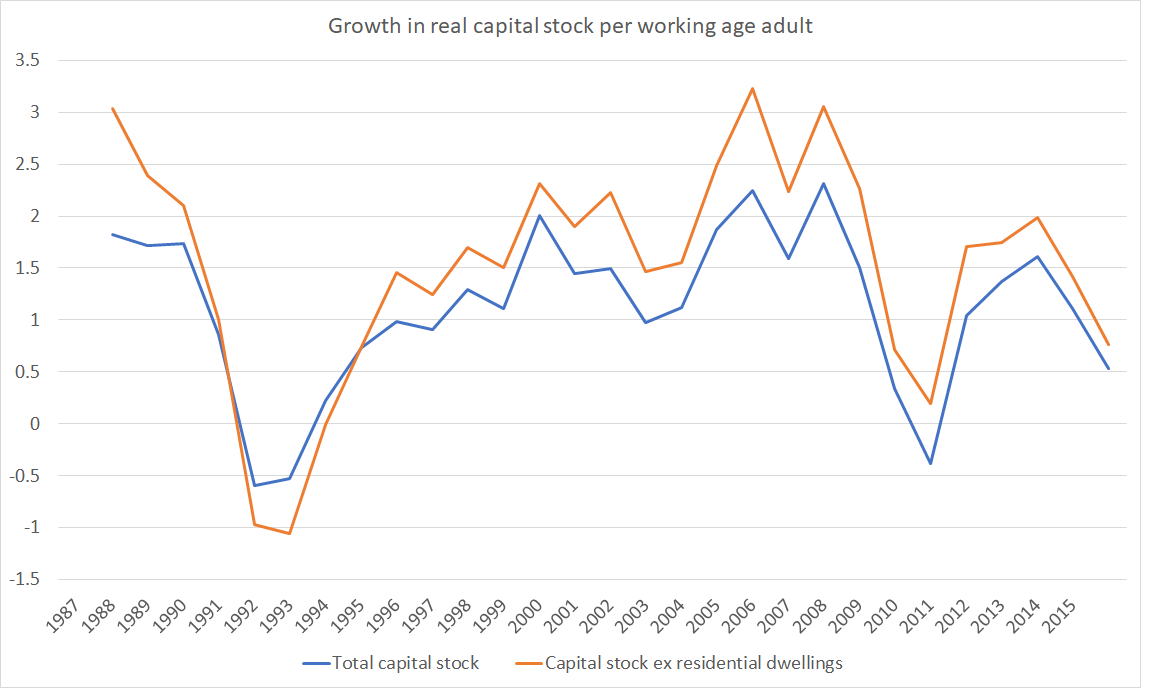

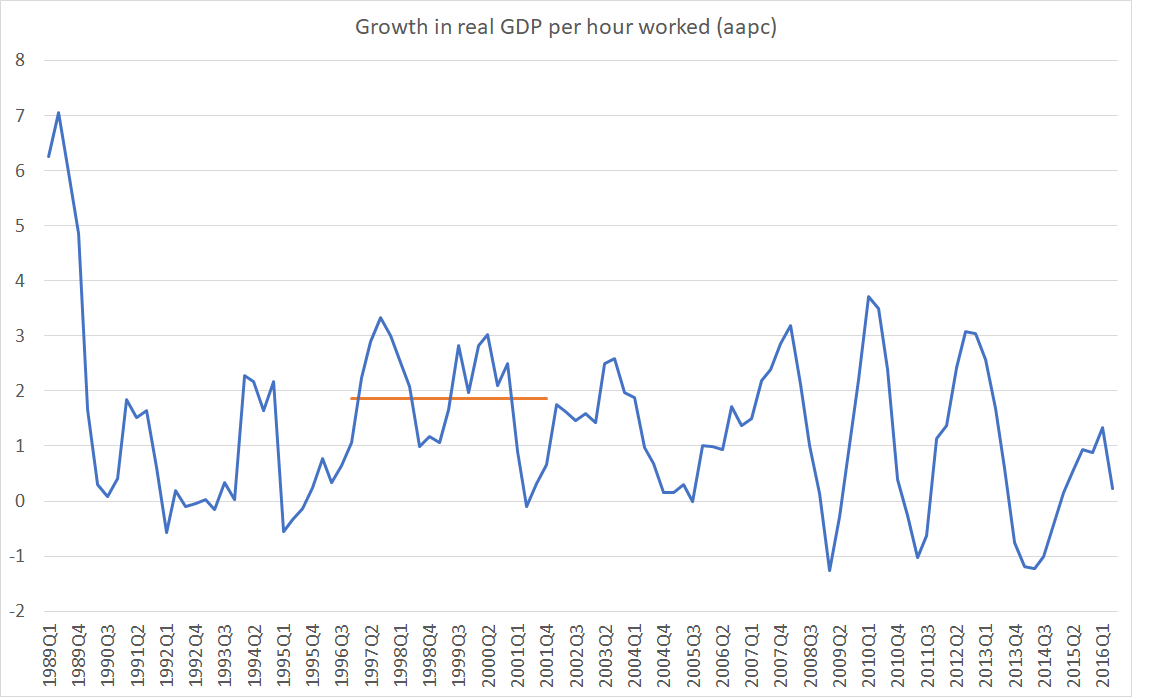

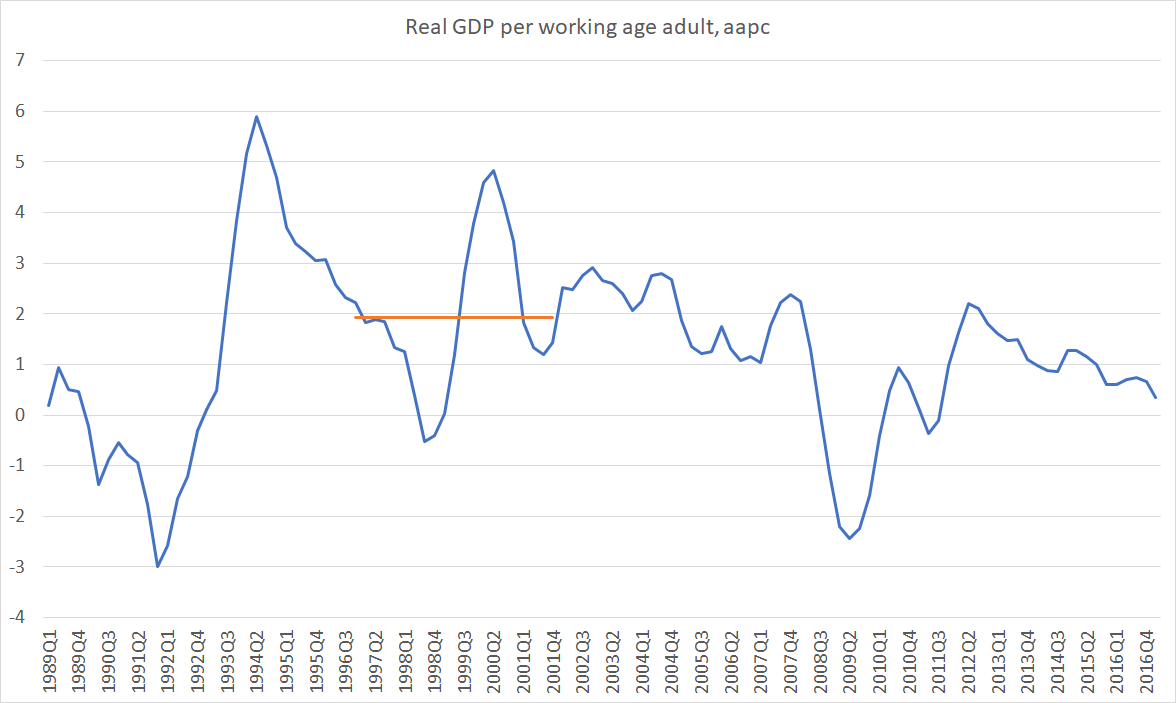

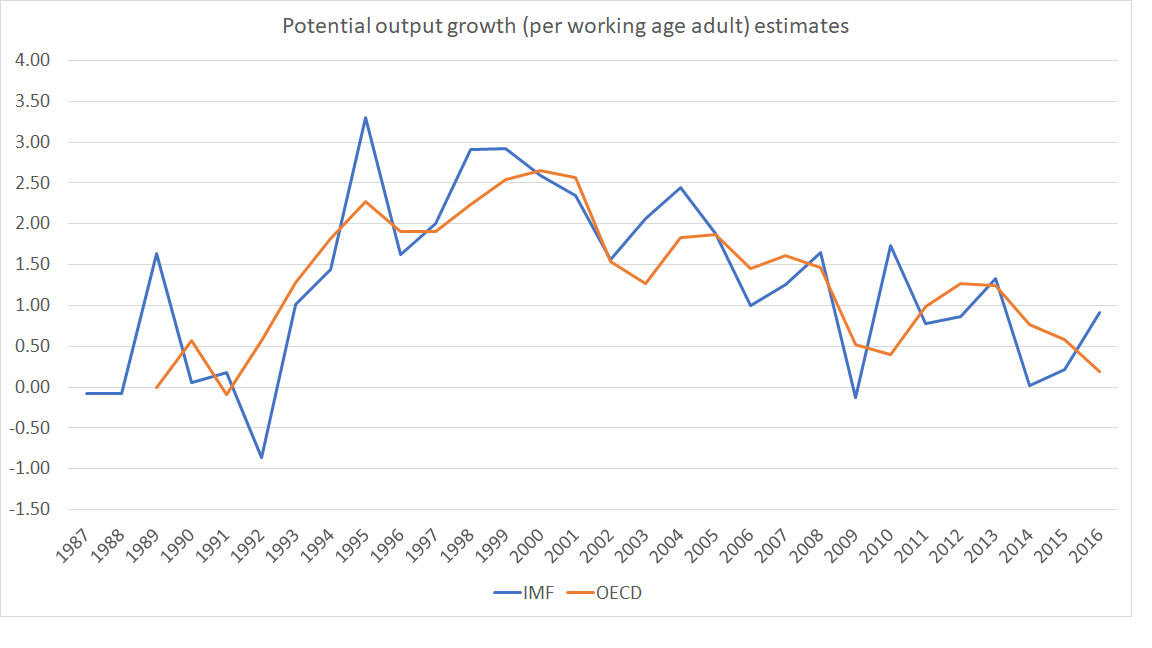

There isn’t anything startling about 1996 itself, but at least on these measures potential output growth in the late 1990s was estimated to have been stronger than before or since.

There isn’t anything startling about 1996 itself, but at least on these measures potential output growth in the late 1990s was estimated to have been stronger than before or since.