Last week I wrote about the New Zealand Initiative’s study tour to Switzerland, where (so we were told) a large and high-powered group of CEOs and chairs were seeking to learn from Switzerland’s success. As I noted, it seemed odd to look for inspiration from the one OECD country that has managed to achieve less productivity growth than New Zealand since 1970. Even since 1990, Swiss productivity growth has underperformed New Zealand’s own poor record.

I learned about this tour in an article in the Herald, written by veteran journalist (and apparently “Head of Business at NZME”) Fran O’Sullivan. It was presented as a straight news story, with no suggestion of any Herald involvement with the trip.

But in today’s Herald O’Sullivan devotes her column to Five elements of a good first Budget. I’ll come back to the substance of the column in a moment. But in the middle of the column was this

From a distance (in Switzerland travelling with the NZ Initiative to look at how New Zealand can once again become a “rich country”) it is easy to overlook that for some nations – like the Swiss – posting surpluses is mandatory.

So a leading journalist writes about a business lobby-group’s study tour to Switzerland without disclosing that she herself is participating in the tour? One presumes NZME is paying for her to undertake the tour, but even so. Wouldn’t it normally be elementary to let readers know of your involvement when you write up the story? Isn’t it just possible that, in what looked like a straight news story, the fact that the author herself was participating in the tour might colour the angles put on trip, and reports of what it might reasonably hope to achieve? It will be interesting to hear, in due course, what O’Sullivan makes of the Swiss experience, but how likely is that we will get a balanced and rigorous account when she has gone in with the New Zealand Initiative to do this trip, running their advance lines about “lessons to be learned” etc (and presumably NZI organised everything, arranged the programme of meetings etc)? Presumably at a distance, she still hadn’t noticed that while Switzerland is pretty rich, its productivity performance has been shocking, and it has slowly but steadily been dropping down the league tables.

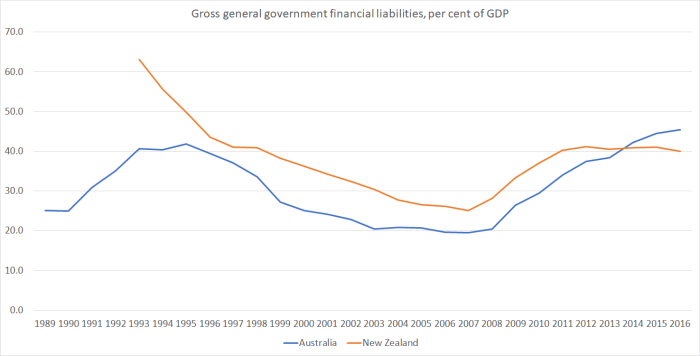

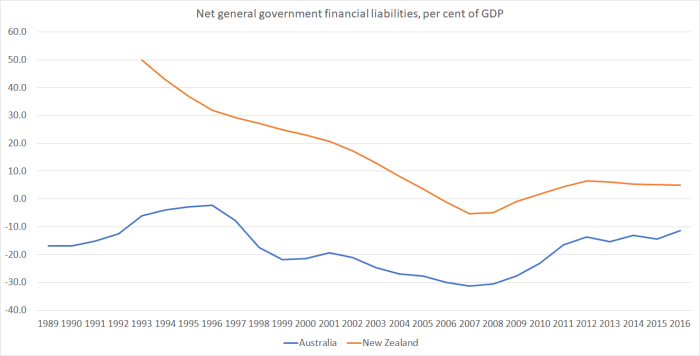

That quote come from item 2 in O’Sullivan’s list of five elements she wants to see in Steven Joyce’s Budget tomorrow. And yes, the Swiss have changed their constitutional rules to require budget surpluses, but as the chart in my post this morning showed, on net government debt (as a share of GDP), they are virtually identical to New Zealand, and both of us have a bit more debt than Australia. Perhaps a formal binding surplus rule might make some sense – although when you don’t have a formal constitution it would be hard – but the case doesn’t seem that compelling in a country that successfully maintains low public debt itself, and yet is exposed to very nasty (and very costly) natural disasters.

What are the five items O’Sullivan looks for?

First – for G*d’s sake, be bold

Second: Post a surplus?

Third: Budget is the plan

Fourth: Get economic growth up on a per capita income level

Fifth: Strip out the smoke and mirrors

Item 1 is the sort of item that helps reinforce conservatives in their conservatism. Being bold might sound good, but her lead proposal is simultaneously bold and daft.

A bold Budget would unveil a significant long-term investment in the country’s infrastructure. For example, a high-speed railway network to service Auckland from elsewhere in the Golden Triangle (Hamilton, Whangarei, Tauranga).

This generation’s Think Big, if I hadn’t already applied that label to our immigration policy.

The British government is envisaging spending 55 billion pounds – stop and take in the number – on their HS2 high speed rail route. There is plenty of scepticism about that proposal – and this is country with many many more people, at either end of the proposed routes, than anything we are ever (or even just in our lifetimes) likely to have in northern New Zealand. If the costs in New Zealand were similar, that would be $100 billion (or around 40 per cent of current GDP). We do lots of government capital spending badly in this country – check out the Transmission Gully project – but an HS2 equivalent would surely take the cake?

Urging boldness on politicians is fine, if there is a strong and well-grounded agreement on what they should be bold about. Otherwise, it feels a lot like random action because “something must be done” and anything is something.

She poses a question mark around the second item – post a surplus. This seems to be because she is tantalised by the idea of using surpluses to fund “major infrastructure to support growth”. As I noted this morning, government infrastructure may involve ongoing maintenance and depreciation costs, but straight government capital expenditure doesn’t show up in the operating balance.

What of the third item – the plan.

Does the Government have a plan? New Zealand is at a choke point. There needs to be a credible five-year plan to capitalise on the major influx of immigrants. Ensure New Zealanders can be housed; clean up our waterways … the list goes on.

Joyce has had a lengthy eight-year period as English’s understudy.

That’s more than enough time to come up with a plan.

Hard to disagree that a credible plan would be nice. After eight years it doesn’t seem likely that one will suddenly be granted us. And, given the Minister’s penchant for interventions all over the place (universities, student visas, tech schemes etc), it isn’t likely that any such plan now would offer us a credible way forward. He was, after all, the Minister primarily responsible for the exports target. Over recent years, we’ve been moving away from that target rather than towards it.

The fourth item – lifting per capita growth – is really the same as the third. It would be nice – rather more than that actually. But there isn’t much sign of doing differently things that have given us such weak per capita GDP and productivity growth for the last eight years.

On the fifth item – smoke and mirrors – one can only agree.

Joyce – like previous Finance Ministers – will be a fail on this score. He is unlikely to strip out the “smoke and mirrors” which politicians use to overstate government expenditure; particularly on social programmes such as housing.

He’s already been caught out by Labour’s Grant Robertson when it comes to massaging the numbers on an $11 billion investment in infrastructure.

Robertson labelled the $11b figure as “just playing with numbers”.

“When you peel it all back, what you have is National only promising to spend an extra $300 million a year from the promise made in the half-year Budget update.”

Finance Ministers really shouldn’t play this game and Treasury should issue tables which keep a running track of “re-announcements” of spending promises.

It is the sort of reason why Treasury forecasts and fiscal reporting are supposed to be done at arms-length from the Minister of Finance. Each time ministers do this stuff it erodes, just a little further, what remaining confidence the public might have in our elected leaders. A cheap (brief) win, and a long-term cost.

In the end, it is a pretty bleak column. Plenty of stuff to wish for – much of it quite sensible, provided you forget about the high speed train – and little prospect of any of it happening.

But I still can’t help thinking that we deserve a lot better from a leading journalist in the country’s largest circulation newspaper than a story writing up and promoting the activities of a lobby group, only to find out 10 days later that the journalist in question is herself a participant in that same (apparently rather misguided) study tour.