Winston Peters was interviewed on the weekend TV current affairs shows. Any sense of specifics on his party’s immigration policy seemed lacking – perhaps apart from something on work rights for foreign students. But I rather liked his line that while ministers and officials have been telling us for years that we have a highly-skilled immigration policy, all we hear now is all manner of industries employing mostly quite low-skilled people telling us how difficult any cut back in non-citizen immigration would be.

But what really caught my attention was when, in his TVNZ interview, Peters reiterated his view that what New Zealand really needs, in reforming monetary policy and the Reserve Bank, is a Singapore-style system of exchange rate management. It was also highlighted in his speech on economic policy last week. It is clear, specific, unmistakeable….and deeply flawed. It seems to be a response to an intuition that there is something wrong about the New Zealand exchange rate. In that, he is in good company. The IMF and OECD have raised concerns over the years. And so have successive Reserve Bank Governors. I share the concern, and I devoted an entire paper to the issue at a conference on exchange rate issues that was hosted by the Reserve Bank and Treasury a few years ago, and which was pitched at the level of the intelligent layperson interested in these issues. Another paper looked at a variety of alternative possible regimes, including (briefly, from p 45) that of Singapore.

What is the Singaporean system? In addition to the brief summary in the RBNZ paper I linked to in the previous paragraph, there is a good and quite recent summary of the system in a paper published by the BIS written by the Deputy Managing Director of the Monetary Authority of Singapore MAS).

The key feature of the system is the MAS does not set an official interest rate (something like the OCR). Rather, they set a target path (with bands) for the trade-weighted value of the Singaporean dollar, and intervene directly in the foreign exchange market to manage fluctuations around that path. There is a degree of ambiguity about the precise parameters, but the system is pretty well understood by market participants. Interest rates of Singapore dollar instruments are then set in the market, in response to domestic demand and supply forces, and market expectations of the future path of the Singapore dollar. It has some loose similarities with the sort of approach to monetary policy operations the Reserve Bank of New Zealand adopted for almost 10 years in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and which we finally abandoned in 1997 (actually while Winston Peters was Treasurer). It is also not dissimilar to the approach – the crawling peg – used in New Zealand from 1979 to 1982 (at a time when international capital flows were much more restricted).

There is no particular reason why a country cannot peg its exchange rate, provided it is willing to subordinate all other instruments of macro policy (and short-term outcomes) to the maintenance of the peg. It is what Denmark does, pegging to the euro. Singapore’s isn’t a fixed peg, but the macroeconomics around the choice are much the same.

It is a model that can work just fine when the economies whose currencies one is pegging to are very similar to one’s own. Denmark probably qualifies. In fact, Denmark could usually be thought of as, in effect, having the euro, but without a seat around the decisionmakers’ table.

It doesn’t work well at all when the interest rates you own economy needs are materially higher than those needed in the economies one is pegging too. Ireland and Spain, in the years up to 2007, are my favourite example. Both countries probably needed interest rates more like those New Zealand had. In fact, what they got was the much lower German interest rates. That had some advantages for some firms. But the bigger story was a massive asset and credit boom, materially higher inflation than in the core countries, and eventually a very very nasty and costly bust. Oh, in the process of the boom the real exchange rates of Spain and Ireland rose substantially anyway. Because although nominal exchange rate choices – the things that involve central banks – can affect the real exchange rate in the short-term, the real exchange rate is normally much more heavily influenced by things that central banks have no control over at all.

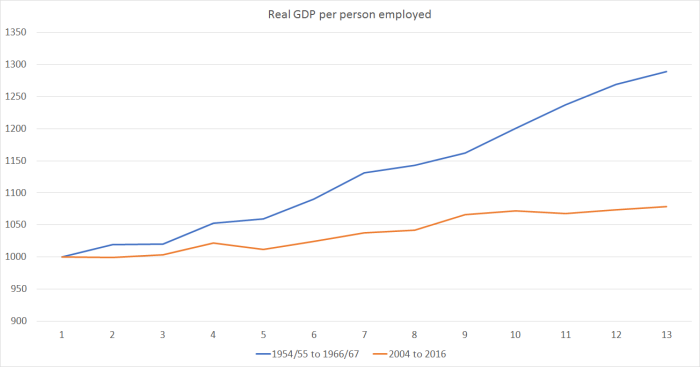

One can, in part, understand the allure of Singapore. It is, in many respects, one of the most successful economic development stories of the post-war era. Productivity levels (real GDP per hour worked) are now similar to those of the United States, and places like France, Germany and the Netherlands, and real GDP per capita is higher still. You might value democracy and freedom of speech (I certainly do), but if Singapore’s achievement is a flawed one, it is still a quite considerable one. And if Singapore is todaya big lender to the rest of the world, it wasn’t always so. Like New Zealand (or Australia or the US) net foreign capital inflows played a big part for a long time. As recently as the early 1980s, Singapore was running annual current account deficits of around 10 per cent of GDP.

And the Singaporean model is not one of an absolutely fixed exchange rate. It is a managed regime (historically, “managed” in all sorts of ways, including direct controls and strong moral suasion). It produces a fairly high degree of short-term stability in the basket measure of the Singapore dollar. But it works, to the extent it does, mostly because the SGD interest rates consistent with domestic medium-term price stability in Singapore are typically a bit lower than those in other advanced countries (in turn a reflection of the large current account surpluses Singapore now runs – national savings rates far outstripping desired domestic investment). As the Reserve Bank paper I linked to earlier noted

From 1990 to 2011, the average short term Singapore government borrowing rate was 1.8 percent p.a. below returns on the US Treasury bill.

Those are big differences (materially larger than the difference between the two countries’ average inflation rates). And they mean that Singapore dollar fixed income assets are not particularly attractive to foreign investment funds. By contrast, New Zealand’s short-term real and nominal interest rates are almost always materially higher than those in other advanced countries. Partly as a result, even though Singapore’s economy is now materially larger than New Zealand’s, there is less international trade in the Singapore dollar than in the New Zealand dollar.

Winston Peters has talked about wanting a lower and less volatile exchange rate. He has given no numbers, but lets do a thought experiment with some illustrative numbers. The Reserve Bank’s TWI this afternoon is just above 75. Suppose one thought that was, in some sense, 20 per cent too high, and so wanted to target the TWI in a band centred on 60, allowing fluctuations perhaps 5 per cent either side of the midpoint (so a range of 57 to 63). What would happen?

The Minister of Finance might instruct the Reserve Bank to stand in the market to cap the exchange rate (TWI) at 63. If our interest rates didn’t change, the Reserve Bank would be overwhelmed with sellers (of foreign exchange) wanting to buy the cheap New Zealand dollar. After all, you could now earn New Zealand interest rates – much higher than those abroad – with very little downside risk (certainly much less than there is now). In the jargon, people talk about “cheap entry levels”. There is no technical obstacle to all this. The Reserve Bank has a limitless supply of New Zealand dollars, but in exchange would receive a huge pool of foreign exchange reserves (it is quite conceivable that that pool could be several multiples of the size of New Zealand’s GDP, so large are the markets and so small is New Zealand).

Ah, but the Singaporean option doesn’t involve interest rates remaining at current levels. Rather, they are now set in the market. And so, presumably, our interest rates would fall, probably very considerably. In the current environment, they might even go a little negative. That would deal with the short-term funding cost problem associated with the huge pool of reserves. But what would happen in New Zealand with (a) a much lower exchange rate, (b) much lower interest rates, and (c) all other characteristics of the economy unchanged? The answer isn’t that different to what we saw in Spain and Ireland. Asset prices would soar, credit growth would soar, general goods and services inflation would pick up quite considerably. Of course, there would be more real business investment and more exports, at least in the short term. And that would look appealing, but as time went by – and it wouldn’t take many years – the real exchange rate would be rising quite quickly and substantially (as domestic inflation exceeded that abroad). Export firms would be squeezed again. If anything, the higher domestic inflation would lower domestic real interest rates even more, so the credit and asset boom would continue. And before too long it would end very badly.

That might sound over-dramatic. And if the ambition was simply to stabilise the exchange rate around current levels, things probably wouldn’t go too badly for a while. But Peters has been pretty clear that his aim is a lower exchange rate, not just a less volatile one.

The lesson? You simply cannot ignore the structural features of the economy that give rise to persistently high real interest rates, and a high real exchange rate. And those features have nothing whatever to do with the Reserve Bank or monetary policy. They are about forces, incentives etc that influence the supply of national savings, and the demand for domestic investment (at any given interest rate). All that ground is covered in my earlier paper linked to above.

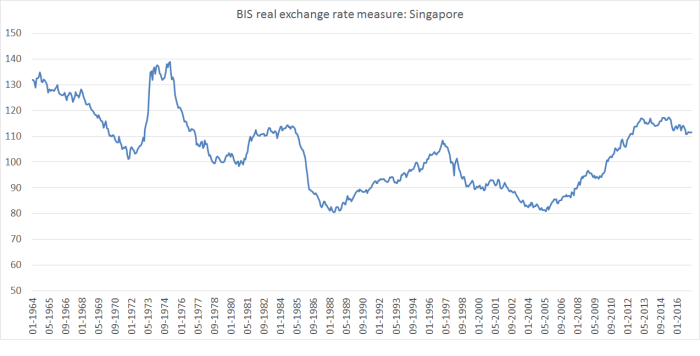

Of course, the Singaporeans also increasingly can’t ignore those forces. Decades ago, global financial markets weren’t that well-integrated, and the Singaporean web of controls was pretty extensive. For some decades, even as Singaporean productivity growth far-outstripped that of other advanced countries, Singapore’s real exchange rate was not only pretty stable, it was falling. Here is a chart of the BIS measure of Singapore’s real exchange rate all the way back to 1964. The current system of exchange rate management didn’t start until about 1980.

It was, in many ways, an extraordinary transfer from Singaporean consumers to Singapore-operating exporters. The international purchasing power the economic success should have afforded consumers and citizens kept getting pushed into the future.

But even in Singapore, these things don’t last forever. Look at that last 10 years or so, when the real exchange rate has appreciated by around 35 per cent. The real value of the SGD is still miles lower than where long-term economic fundamentals suggest they should be – consistent that, the current surplus is still around 18 per cent of GDP – but there has been a lot of change in its value over that time. For many firms even in Singapore that must have been a challenge. With US interest rates near-zero for much of that time, historically low Singaporean rates will have afforded the authorites fewer degrees of freedom than they had had previously.

(The Singapore authorities impose all sorts of other controls, including their compulsory private savings scheme and increasingly onerous direct controls on private credit. I’m not going there in this post, partly because it will already be long enough, and partly because what I’ve heard from NZ First is about the exchange rate system in isolation).

Singapore is a (hugely-distorted) economic success story in many respects. Some mix of the people, the policies and institutions, and the favourable geographical location all helped. Nonetheless, it some ways it is an odd example for New Zealand First to favour.

For example, Singapore has had an extremely rapid population growth, mostly immigration-fuelled, in recent decades. Here is a chart of Singapore’s population growth and that of Australia and New Zealand.

(On my telling, Singapore has had opportunities, and lots of savings, and thus rapid population growth made sense, enabling more of those opportunities to be captured, even while real interest rates stayed lower than elsewhere – although not, presumably, as low as they would otherwise have been.)

And Singapore’s economy is pretty volatile. Sadly, the IMF doesn’t publish output gap estimates for Singapore, but the MAS estimates (in that document I linked to earlier) suggest much more volatility than we see in New Zealand or most other advanced economies. And here is annual growth in real per capita GDP for New Zealand, Australia and Singapore.

Hugely more volatile than anything we are accustomed to (and in recent years, interestingly, not even materially higher).

And for all that the MAS likes to emphasise the close connection between the exchange rate and inflation, here are the inflation rates of the three countries.

On average, the differences aren’t that large, but even in the last 15 years or so Singapore’s inflation rate has been more volatile than those of Australia and New Zealand.

It isn’t really clear that Singapore’s system is even serving them that well these days.

But what of exchange rate comparisons? You might have supposed that Singapore’s exchange rate was a lot less volatile than New Zealand’s. But here, from the RB website, is the monthly data for the SGD and the NZD, in terms of the USD since 1999.

And, yes, the New Zealand dollar is more volatile in the short-term, but even there over the last seven years or so the differences are pretty small. And if hedging isn’t always easy, particularly for firms without large physical assets, it is a lot easier to hedge those sorts of short-term fluctuations than it is the longer-term real exchange rate uncertainty. (And, of course, given Singapore’s faster productivity growth, you might still be troubled that our exchange rate has more or less kept pace with theirs, but that is a real and structural issues, not one that can be fixed by fiddling with the exchange rate system.)

As it happens, Australia is our largest trade and investment partner. Here is how our exchange rate, relative to the Australian dollar, compares with the Singapore dollar relative to the US dollar.

It is an impressive degree of stability. Again, in the very short term the New Zealand exchange rate is a bit more volatile, but it isn’t obvious that for longer-term planning purposes New Zealand exporters have had it tougher – on the volatility front at least – than those operating from Singapore.

And, as a final chart, this one uses the BIS’s broad real exchange rate indices to illustrate movements in the real exchange rates of Singapore, New Zealand, and (another export-oriented development success story) Korea.

Singapore’s real exchange rate has certainly been the most stable of the three, but if anything Korea’s has been more volatile than New Zealand’s. It would clutter the gaph to have added it, but Japan’s real exchange rate has also been more volatile than New Zealand’s.

There are real exchange rate issues for New Zealand. The fact that our real exchange rate hasn’t fallen, even as relative productivity performance has fallen away badly, is a crucial symptom in our overall long-term disappointing economic performance. It has meant we’ve been less open to the world (lower exports, lower imports) than one would have expected, or hoped. But the issue isn’t primarily one of volatility – which is mostly what the Singaporean system now tries to address – but of longer-term average levels. This real exchange rate symptom appears to be linked to whatever pressures (NB, not superior economic performance) have given us persistently higher real interest rates than the rest of the world. New Zealand First, and other parties, would be much better advised to focus their analysis, and proposed policy solutions, on measures that might directly address these real (as distinct from monetary) issues. As it happens, a much lower trend rate of immigration seems likely to be a strong contender for such a policy – taking pressure off domestic demand for resources, and freeing up resources to compete internationally. Singapore simply isn’t the answer.