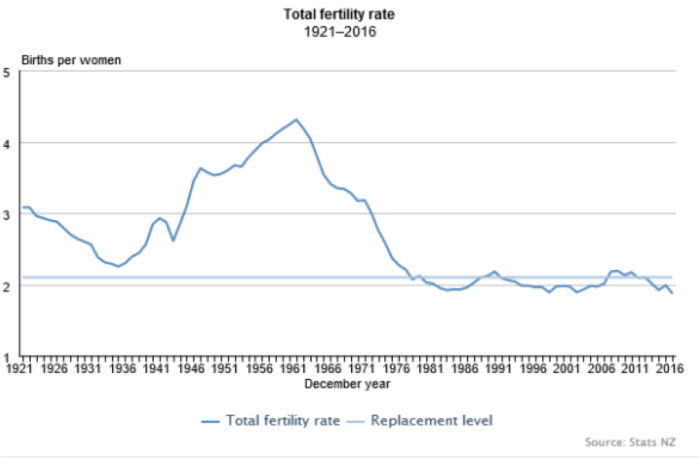

The other day Statistics New Zealand released the annual data on New Zealand birth rates. There was some coverage of the continuing drop in teen birth rates (it was what SNZ highlighted), but the chart that caught my eye was this one.

I’d been under the impression that New Zealand’s birth rate was at, or just above, replacement (roughly 2.1 births per woman, thus allowing for early deaths). And, according to this summary indicator, it was for a few years not that long ago. But that is no longer the case.

But what most interested me – and it isn’t data I’ve ever paid that much attention to – was the longer-term averages. It turns out that for forty years now, New Zealand’s birth rate has averaged below the replacement rate (1977 was the last year the TFR had been persistently above 2.1).

This is how we compare with other OECD countries.

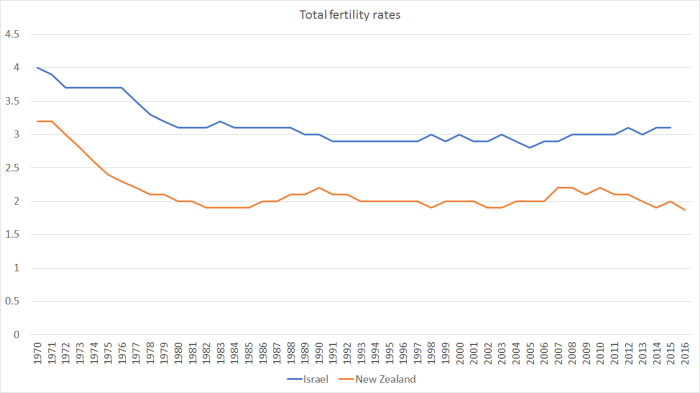

New Zealand is still towards the right of the chart. But note that only two OECD countries now have total fertility rates in excess of replacement – one (Mexico) just barely. The country that really stands out is Israel, with a TFR of 3.1. New Zealand hasn’t been that high for 45 years.

(Diverting off topic for a moment) the gap between Israeli and New Zealand birth rates has been there for a long time.

At one stage, the high Israeli birth rates were all about the Arab population, but apparently the Jewish and Arab-Israeli birth rates are now equal (Arab rates falling and Jewish rates – especially among the orthodox – rising. (Israel also has a lot of immigration – together they explain the very rapid population growth I highlighted yesterday – but that is a topic for another day.)

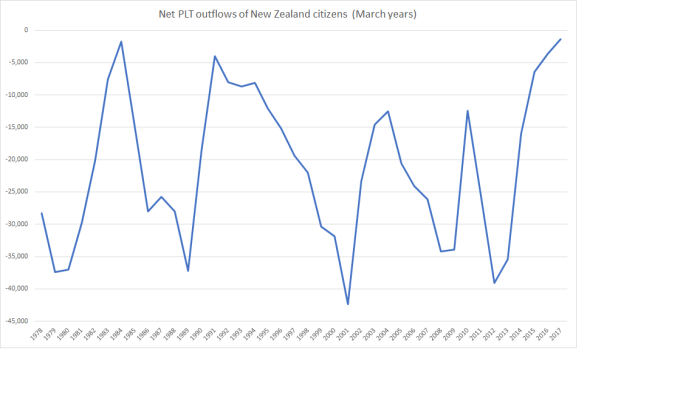

For forty years, New Zealanders in aggregate have been choosing to have slightly fewer children than would, all else equal, maintain the population. But over that same period, there has also been a very large outflow of New Zealanders moving permanently to other countries (especially Australia). In the forty years to March 2017, the estimated net outflow (as recorded in the PLT data, with all their limitations) of New Zealand citizens was 845,520.

There is a lot of cyclical volatility, but in not a single year in that period has the flow of New Zealand citizens been back to New Zealand. In fact, the last time the data record a net inflow of New Zealand citizens was the year I was born. By international standards, it is a staggering loss of our own people (more than 20 per cent of the average total population over that period). I can’t think of any other functioning democracy in the last 100 years that has had such a large percentage outflow of its own people.

These New Zealanders have presumably been making their own choices and assessments about the opportunites for themselves and their (actual or potential) children. Not only have they chosen to have not quite enough children to maintain the population, but many of them (us) have also decided that the opportunities abroad are simply better than those here. Not all of them will necessarily have made the right choice, but average we should presume that it was a rational choice. These aren’t simply patterns based on a single year’s whim, a single year’s bad news.

So New Zealanders’ own choices, about their own lives, would have set in train a process that would see a gradually falling population in New Zealand. Immigration policy, regarding the access of non-citizens, dramatically reversed that, and has in fact given us one of the fastest population growth rates in the advanced world over recent decades. You have to wonder what insights, and wisdom, our politicians and officials are blessed with that leads them to run a policy operating directly to undermine the effect of the choices of individual New Zealanders. Perhaps they might share that wisdom, that research, with us one day, before they further worsen the prospects of the New Zealanders who chose to stay living here.

Declining populations do create some issues, as fast-growing ones do. Over history – even modern New Zealand’s short history – many places have grown, and then faded away. On the whole, it might be better to live in place that had so many opportunities, it could maintain strong productivity growth and offer those gains to more people (at least if transport and housing messes could be sorted out). But one doesn’t fix the fundamental economic challenges – that lead people individually to take actions that mean New Zealand’s population wouldm’t be growing – just by going to a bunch of poorer countries and telling their people they can come here, in large numbers, if they want. But, as I say, perhaps our political leaders could share with us their apparently superior insights and research results, which back their decisions to place their own preferences above the considered choices of New Zealand individuals.