It is now 18 August, and I’m still waiting for MBIE’s response to my 28 May request for copies of advice on the economic impact of immigration and the permanent residence approval target. The Act provides a basic response time for agencies of no more than 20 working days.

Last week I ran a series of posts (here) using data from MBIE’s website on the occupational breakdown of work visas granted for New Zealand over the years 2010/11 to 2014/15. For a skills-focused immigration programme, a remarkably large number of the approvals were in not-obviously highly skilled occupational areas.

But as I noted last week, the 250000 or so approvals on the spreadsheet encompassed a variety of different types of approvals. Around 30000 were for a “specific purpose or event” (perhaps competitors in a professional sports tournament, or performers in a visiting professional orchestra). And more than 20000 were “variation of conditions” approvals, so including them was effectively double-counting people.

But the heart of the list is the category MBIE call “Essential Skills”. Of the 250678 total approvals over those five years, 101296 were applications approved under the Essential Skills category.

Around 2500 of these approvals don’t have an identified occupation, but what of the remaining 99000?

I went through the Essential Skills list and tried to pick out the occupations I’d highlighted last week as not looking overly highly skilled. The chart shows those with more than 200 approvals – starting from the bottom with “Shelf Fillers”. These 39 occupations accounted for almost 43000 of the total Essential Skills work visa approvals, almost 45 per cent of the total. (As previously, I’ve deliberately left out construction-related positions because there is a different set of arguments around the role of temporary migration is dealing with a temporary one-off source of labour demand).

There is quite a range of occupations even on this list. Each person will probably look at the list and think of one or another occupation “oh, but that really is quite skilled”. And I’ve no doubt that most of them do involve some skill or other, but equally I’m pretty sure that looking across the list as a whole it is probably not what most New Zealanders have in mind when they hear that New Zealand has a skill-focused immigration programme, which is supposed to boost our national productivity through the spillovers from this skilled migration to the wider economy. I certainly wasn’t what I had in mind. I’ve been critical of our migration policy on macroeconomic grounds – the sustained pressure on real interest and exchange rates – but have repeatedly accompanied that analysis with lines about “but we seem to focus pretty successfully on bringing in skilled people”.

And, as I’ve noted before, to get a visa under this Essential Skills category one needs to have a firm job offer from a New Zealand employer, which requires meeting this standard:

Evidence there are no New Zealand workers available

To get an approval in principle before you apply, or to show us that there are no suitable New Zealand workers available when you are applying, the employer has to show that they have genuinely searched for suitably qualified and trained New Zealand workers.

The employer also has to explain why:

- their particular job specifications are necessary for the work

- New Zealand applicants are not suitable, and

- New Zealand applicants cannot be readily trained.

There must be a huge amount of search activity going for those elusive chefs/cooks…..

Many other work visas (25000 or so over the five years of this data) are granted to people who are simply partners/spouses of students or someone who has got an Essential Skills visa approval. There appears to be no skill or occupational requirement for these people.

Unfortunately, the MBIE data do not indicate how long each work visa approval was for. For lower-skilled occupations, visas are apparently typically for shorter-periods than those for higher-skilled occupations. That will mean that simply counting total approvals by occupation will overstate the effective share of lowly-skilled labour in the total inflows under the Essential Skills category. But it is not obvious why we are granting Essential Skills work visas to shelf fillers, fast food cooks, cleaners, kitchen hands, waiters , or aged care workers at all. It has the feel of something equivalent to “corporate welfare” – employers smart or lucky enough to get on the list access labour that is cheaper than otherwise. And this is all before we take into account people here on the numerous working holiday schemes.

Work visas are for a limited term, and are distinctly different from permanent residence approvals. Some of the latter are for genuinely quite highly-skilled people (on a skills criterion shelf fillers would not gain permanent residence approval). But as the Treasury material I commented on last week illustrated, in recent years only around half of even permanent residence approvals came under the “Skilled/Business” headings, and that heading included not just the skilled worker themselves (chefs and so on) but their immediate families.

There are all sorts of arguments for immigration. Some make cases on humanitarian grounds (genuine refugees), others on simply targeting a bigger population, some aiming for diversity or “superdiversity”. Some libertarians will even mount an “open borders” argument – that the world would be better off if everyone could simply move to where the opportunities were best for them. But New Zealand governments, over 25 years or so, have focused on skills-based arguments – that a large-scale immigration programme offers a way of supplementing local skills in ways that don’t just boost total numbers but which add to the productivity and living standards not just of the migrants themselves but of the local population.

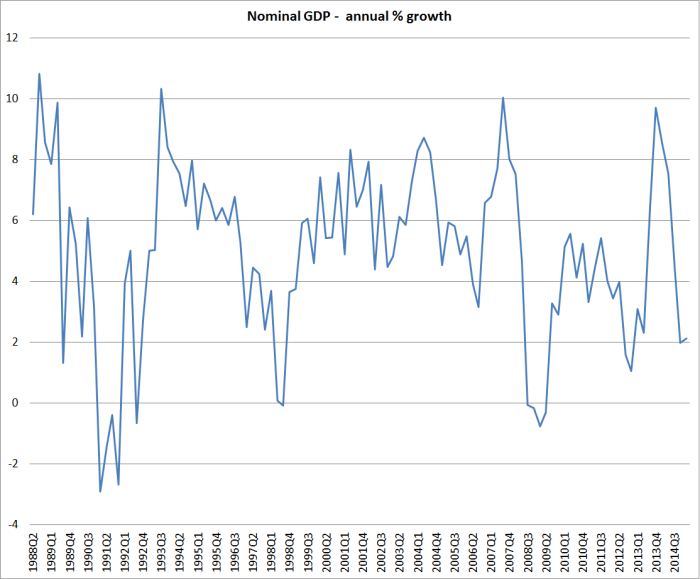

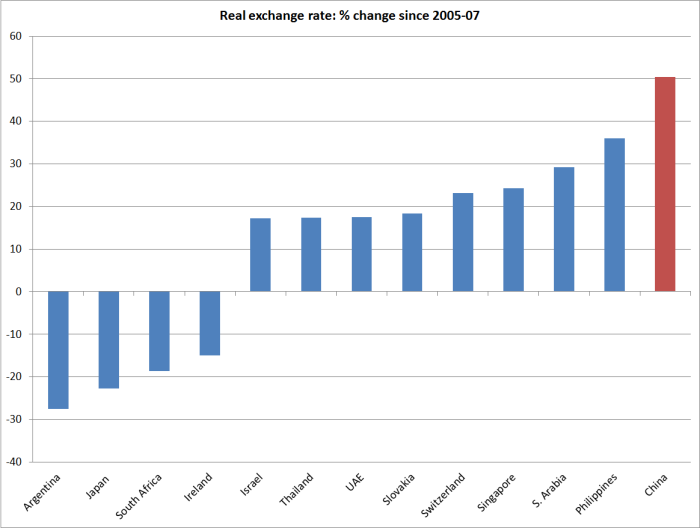

I’m sceptical that we have had any such gains.. On the one hand, New Zealand – while attractive as a place to live – just isn’t that appealing (small, distant, underperforming) as a place to work and grow a business for the hardest-driving and most energetic of people. And the fact that the additional pressures on demand from immigration dominate any supply benefits in the short-term has meant that in a modest-savings economy, high inward immigration has put sustained pressure on real interest rates (highest in the advanced world for the last 25 years) and the real exchange rate. Business investment, especially in the outward-oriented tradables sectors, has suffered, and continues to do so.

But these data tend to illustrate that our immigration programme isn’t really that skills-focused at all. If so, it is hardly surprising that there are few/no signs of beneficial spillovers to the rest of us. And the programme has just been further debauched: as I noted a couple of weeks ago, the government’s recent announcement of additional points for people going to the regions will simply lower the average quality of the migrants we let in. There is a lot of idle talk about attracting really top people, and “the next Bill Gates” is a common shorthand. But our politicians, and their advisers, need to face the fact that New Zealand just isn’t that attractive to such people, even if we could identify them. Our universities are not top-tier. Our market is small. And our country is remote. As even the advocates acknowledge, even among the Anglo countries, why would you choose New Zealand if you could get into the US, the UK, Canada, Australia, or even Ireland (which may be no bigger, and have no better universities, but is within the EU and close to continental Europe).

It is time some pretty hard questions were asked about our immigration programme and strategy. The Australian government has had their Productivity Commission do two reviews in the last decade. It looks like an issue tailor-made for our own Productivity Commission to have a look at. Perhaps the Secretary to the Treasury could then produce the evidence or arguments behind his rather glib assertions about the benefits to New Zealand of our very large immigration programme?