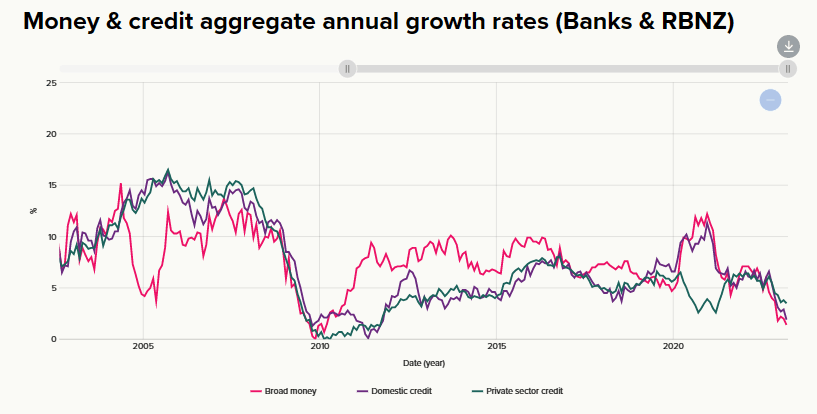

The CPI data out yesterday were not good news.

Annual headline inflation was, more or less as expected, down, but at around 6 per cent is miles from the 2 per cent target midpoint the Reserve Bank’s MPC has been required to focus on delivering. Much more importantly, core inflation measures show little or no sign of any reduction.

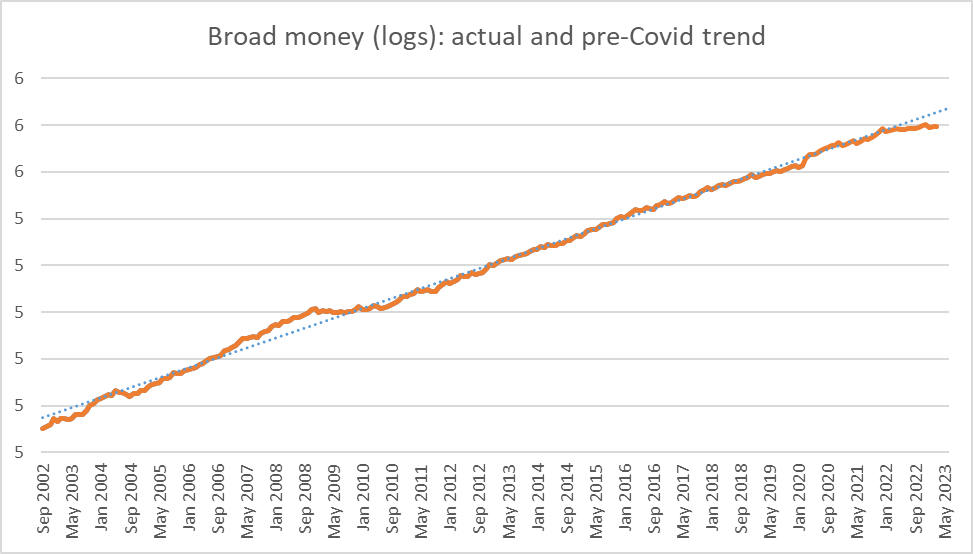

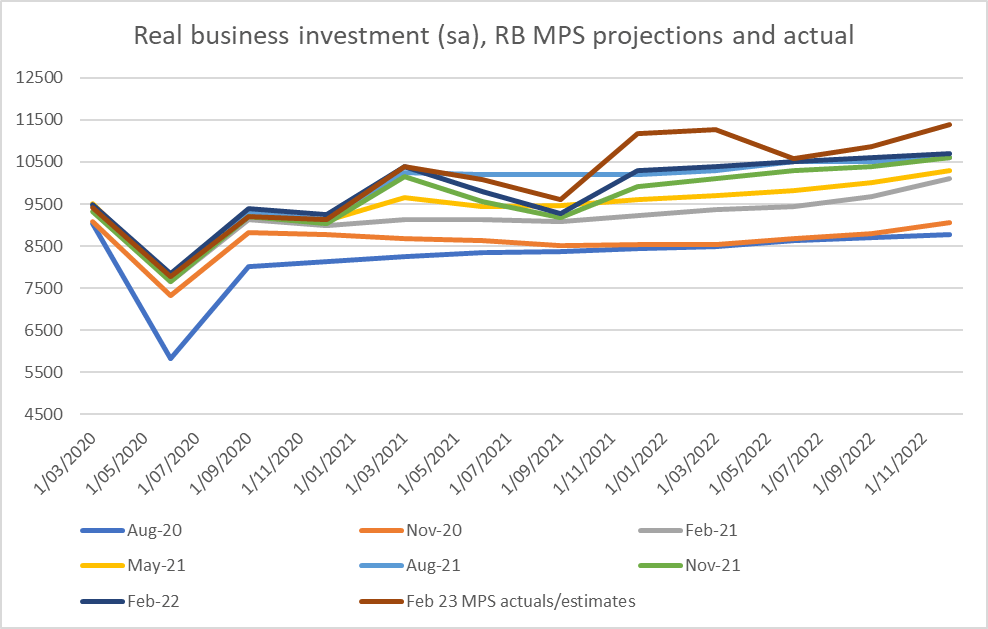

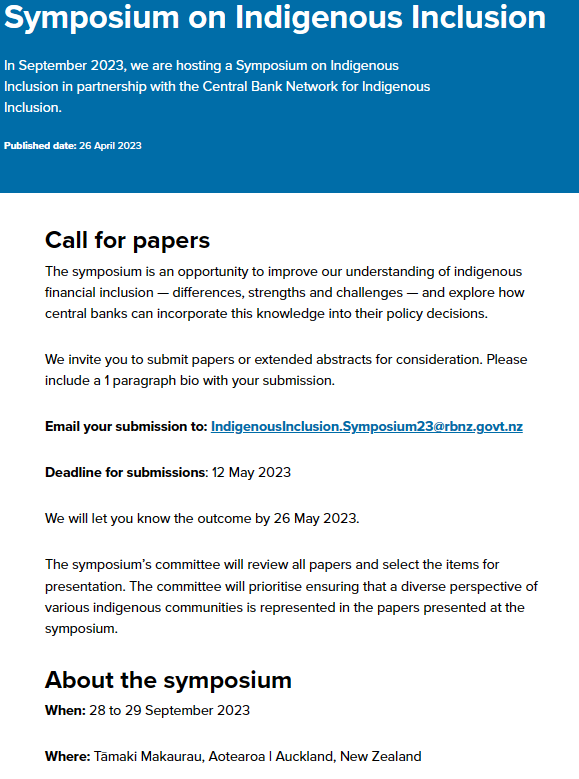

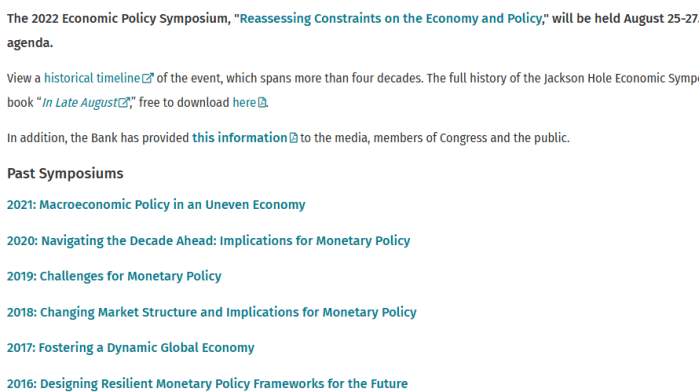

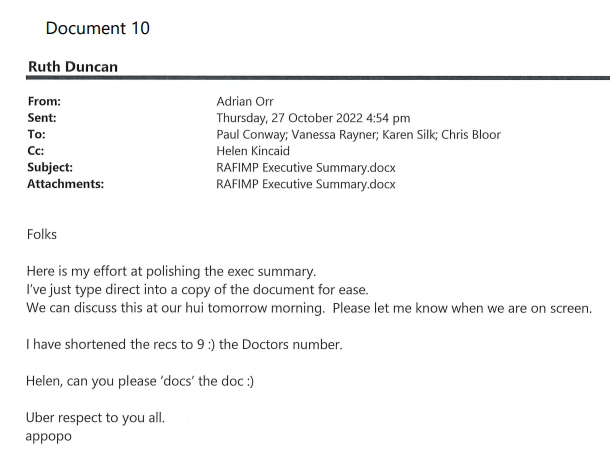

Six months ago I had been intrigued by this chart

It looked as though a reasonable case could then be made that core inflation had peaked a year earlier and was now falling (albeit still far too high).

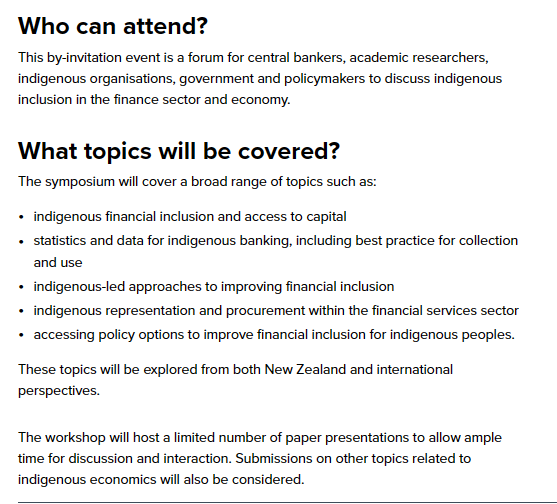

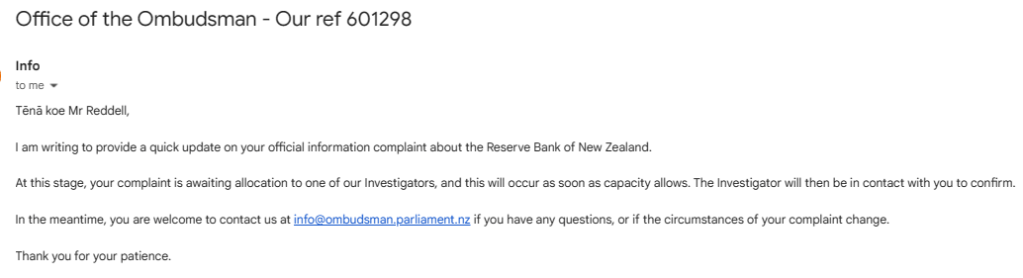

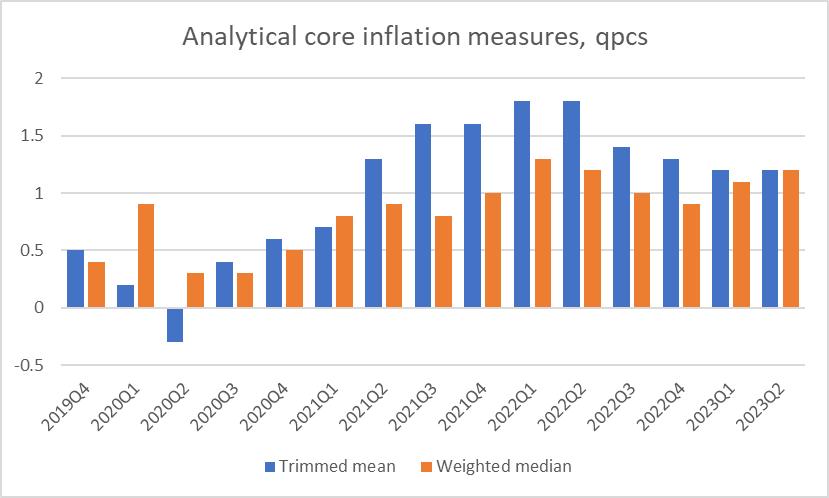

But jump forward to today and the chart now looks like this

If it still suggests a peak at the start of last year (at least on one of the measures), it is no longer a picture of (core) inflation falling now. (NB: You cannot put much weight on the absolute level of the numbers shown here because for some, unknown, reason SNZ persists in doing the calculations on not seasonally adjusted data, which can materially affect the level of quarterly estimates.)

If you look at a range of exclusion measures (CPI ex this, that or the other), the quarterly picture for Q2 looks a little more promising (but analytical measures such as those above are increasingly used for a reason).

On an annual basis, a whole bunch of measures centre on core inflation of perhaps just over 6 per cent.

Focusing on just two big individual price movements, the CPI ex petrol is up 7.1 per cent for the year, and the CPI ex international airfares is up 5.7 per cent.

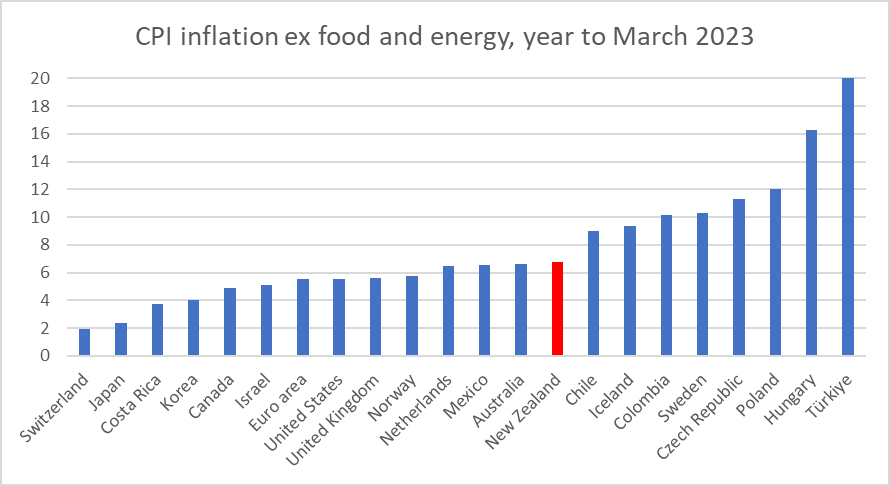

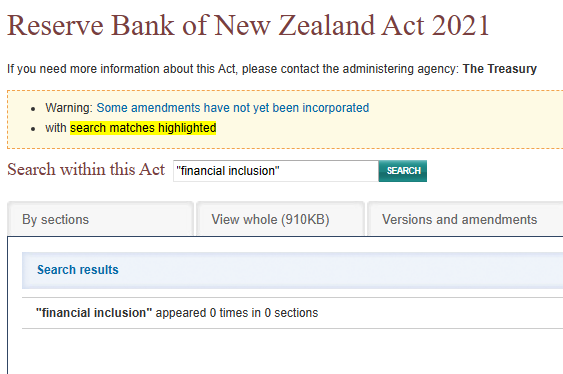

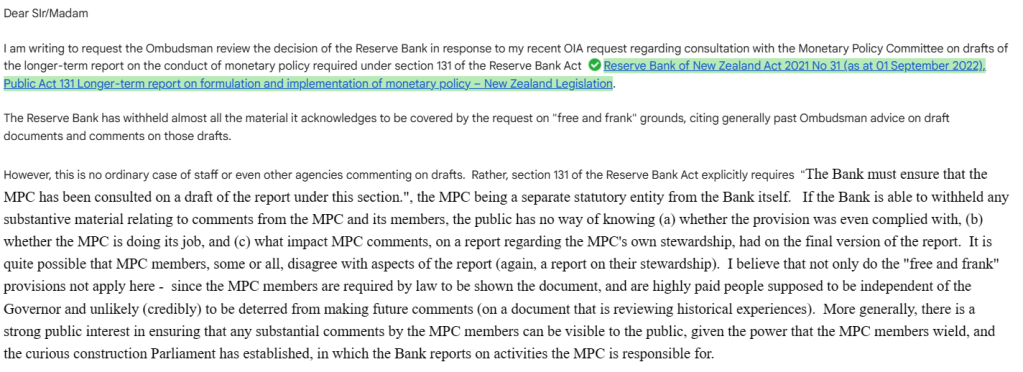

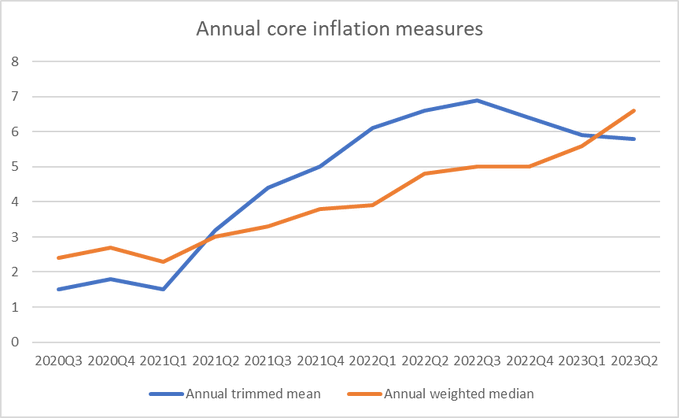

The contrast between New Zealand

and Canada (where the central bank has the same target as ours) is striking

Rightly or wrongly, the Canadian central bank last week still judged it appropriate and necessary to raise its policy interest rate.

Over the period since the OCR was introduced, the New Zealand policy rate has typically been a lot higher than Canada’s (for the same inflation target since 2002): the median difference has been 1.5 percentage points. At present, the difference is unusually small even though our inflation numbers look quite a bit worse than Canada’s

If you think Canada is an obscure comparator, the story is, if anything, a bit more stark relative to the US where core inflation measures have also been falling.

And yet having chosen – and it is pure discretionary choice by the MPC – to review the OCR last week, just a few days BEFORE the infrequent New Zealand inflation data was released, the MPC then declared itself “confident” things were on track to get inflation back to target with policy rates at current levels.

Given how wrong they (and most other central banks) have been over the last three years, it is difficult to know how any bunch of monetary policymakers, with any self-knowledge and introspection at all, can declare themselves “confident” of anything about inflation outlooks. But what could possibly have led our lot to such a conclusion a week BEFORE the (quarterly only) inflation data? Once again, it isn’t looking great for them……and I guess it will be fingers crossed at the RB that the quarterly labour market data out early next month are much weaker. But the best official monthly data we have don’t seem that promising.

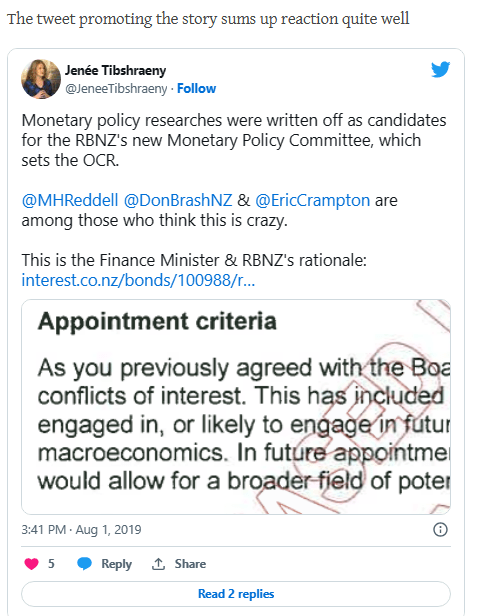

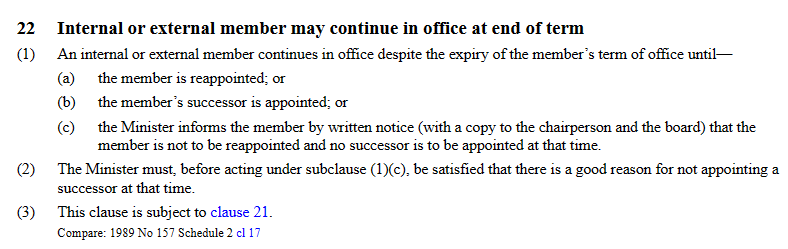

(As a reminder, it is not too late to apply to become a member of the Monetary Policy Committee although it is unclear that genuinely able people would be that keen to join a body led by underqualified uninterested people and where any genuine insight or challenge is unlikely, on the evidence to date, to be welcomed.)

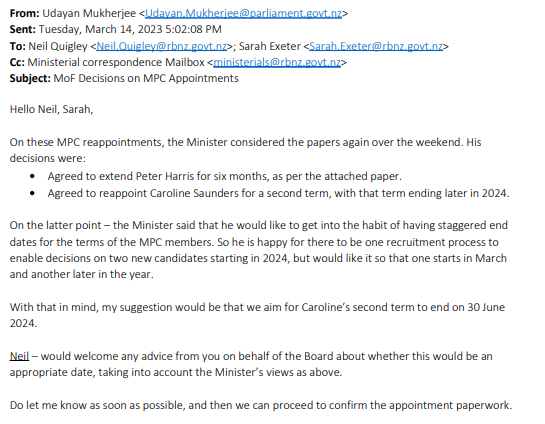

I’ve always been reluctant to suggest that the MPC, or even Orr, were partisan. Mostly, they just seem not very good, something shown up more starkly in challenging times, and prone to questionable self-serving spin (even in front of Parliament). But since the May MPS I have started to wonder, and the nagging doubt was reinforced last week.

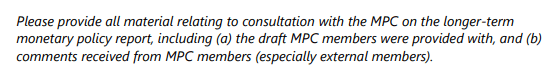

The Minister of Finance brought down the government’s annual Budget on Thursday 18 May. The Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Statement was a few days later, on Wednesday 24 May. I was travelling so most of my scattered comments were on Twitter.

On a current affairs show on 20 May, the Minister of Finance claimed that the Budget would not add to pressures on inflation or monetary policy.

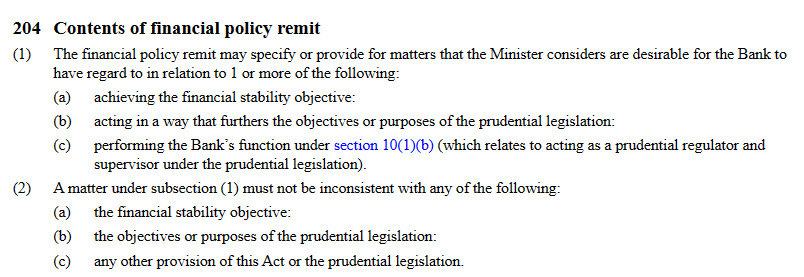

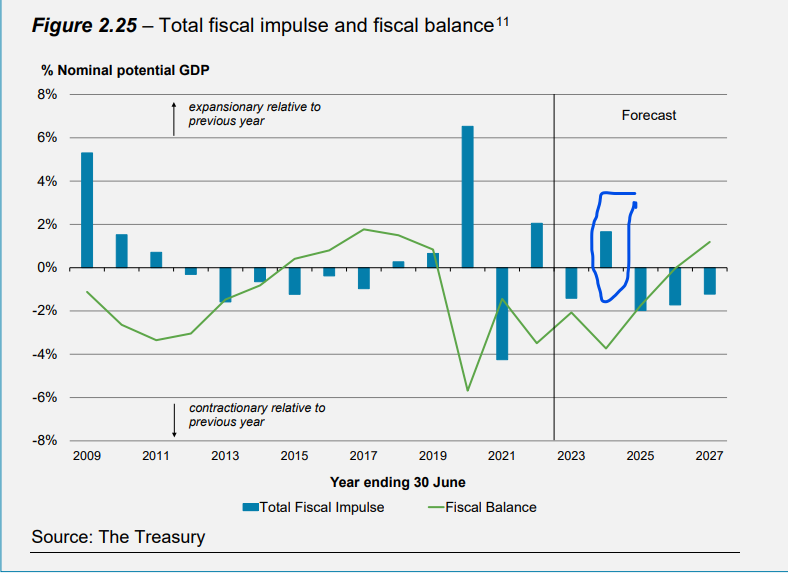

This was utterly at odds with the material published by The Treasury. Treasury estimates and publishes a series for the “fiscal impulse”. This measure was designed specifically for the Reserve Bank to give a sense of how, particularly over the forecast period, fiscal policy choices were going to be affecting demand and inflation pressures.

All else equal a falling deficit or rising surplus act as a bit of a drag on inflation, and vice versa for rising deficits or falling surpluses.

This chart was from the Treasury HYEFU published last December and incorporating the government’s then fiscal plans, as formally advised to the Treasury. As you can see, for each of the forecast years, the estimated impulse was negative (the overall accounts were still expected to be in deficit for most of the period, but the projected deficit was shrinking). At the time, most monetary policy interest would have been on the (highlighted) 23/24 year – showing a moderate negative impulse – since it was the period that monetary policy choices would most affect (and anything beyond 23/24 was little more than vapourware anyway, with an election in the middle).

This is how the same chart looked in the May Budget documents (Treasury’s BEFU)

For the key year – the one for which this Budget directly related – the estimated fiscal impulse had shifted from something moderately negative to something reasonably materially positive. The difference is exactly 2.5 percentage points of GDP. That is a big shift in an important influence on the inflation outlook – which in turn should influence the monetary policy outlook – concentrated right in the policy window.

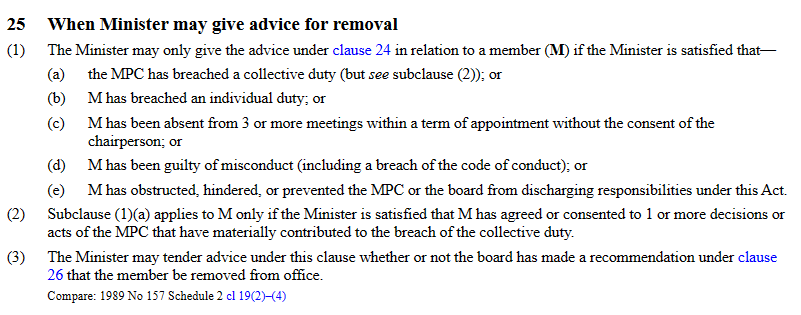

My point is not to debate the merits of the Budget (political parties will differ on that) but to highlight the macro implications of aggregate fiscal choices as estimated by The Treasury, and how utterly at odds with the Treasury’s analysis the Minister’s spin was.

Ministers – and perhaps campaigning ones – will say whatever suits them, whatever relationship (or otherwise) what suits bears to hard analysis and advice.

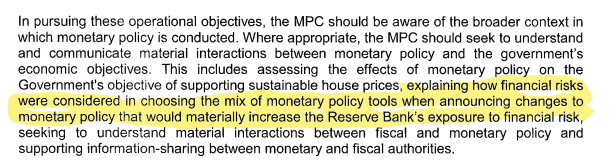

But one of the key reasons why societies have chosen to delegate the operation of monetary policy to autonomous central bankers is that the central bankers are thought more likely to operate without fear or favour, calling the data and events as they calmly and professionally see it. So, you’d have thought, with a Monetary Policy Statement a few days after the Budget one might have expected some serious detached analysis of the updated Budget fiscal numbers, as they affected demand and inflation. Either citing the Treasury’s estimates or perhaps presenting analysis explaining why the Bank thought the fiscal influence might be different than the Treasury did (the latter using a framework designed specifically for monetary policy purposes). After all, in their previous MPS, MPC minutes had explicitly noted that “members viewed the risks to inflation pressure from fiscal policy as skewed to the upside”.

Central bankers, including particularly at our Reserve Bank, have long avoided taking a stance on government spending and revenue choices. Mostly, they also avoid taking a stance of deficits and surpluses. Those are political choices, and particularly in modestly-indebted countries (like New Zealand) it doesn’t greatly matter to monetary policy whether the budget is in deficit or surplus. It matters way less whether one has a high spending and high taxing government or a low spending or low taxing government, and so it is rare – and appropriately so – for the Reserve Bank to be commenting on either spending or revenue choices. What matters (about fiscal policy) in updating the inflation outlook is changes in the discretionary component of the fiscal deficit/surplus (basically, what the fiscal impulse is trying to capture). This snippet (from a Bollard-years MPS) captures the general approach.

But how did the MPC treat things in the May 2023 MPS, coming just a few days after that very big increase in the expected fiscal impulse for the immediately approaching year, at a time when inflation (core and headline) was way outside the target range and the OCR had had to be raised aggressively?

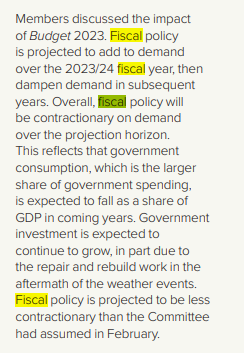

The only uses of the terms “fiscal” or “fiscal policy” (“fiscal impulse” doesn’t appear at all) are in this paragraph from the minutes. Even here – even that final sentence – it is consistent minimisation.

But these are the only references. In the one page policy statement, there is no link drawn from fiscal choices to the inflation outlook, and only this rather odd (for a central bank) detached observation: “Broader government spending is anticipated to decline in inflation-adjusted terms and in proportion to GDP.” So what, one was left wondering…..unless the Governor and his colleagues had taken to playing politics, perhaps to help out a Minister and his colleagues who seem more disposed to the Governor’s way of doing/saying things than, say, the Opposition parties (who openly opposed his reappointment) might be.

Perhaps it wouldn’t even be worth highlighting if this were the only such reference. But it isn’t, by any means. Recall, there are no references in the body of the document to fiscal policy, fiscal impulses, fiscal deficits, OBEGAL, or changes in any of these. But there is a whole section devoted specifically to government spending, on top of the couple of references I’ve already quoted. And the focus there is not on the horizon relevant to May’s monetary policy choices, or the inflation outlook over the next 12-18 months but over the “medium term”, when who knows which government will be in charge and what their spending preferences and priorities will be.

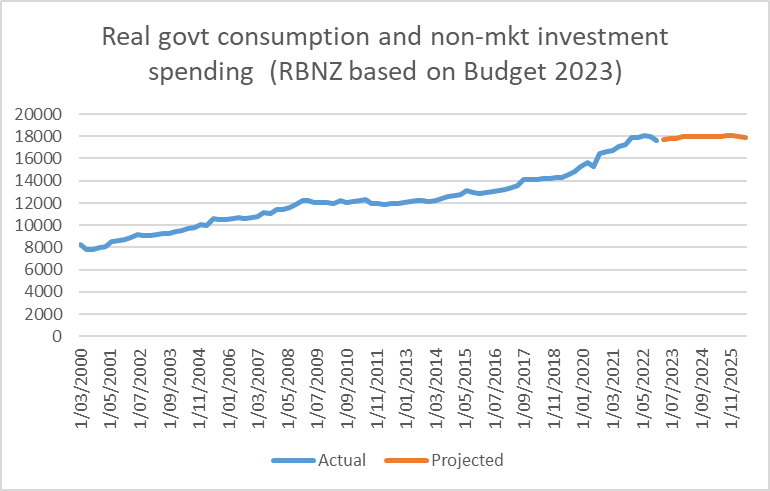

It is quite right that their projections – which simply use Treasury numbers as a base – have real government consumption and investment spending (the bits they publish numbers for) flat for the next several years.

That might raise some interesting issues, including for supporters of the current government who favour lots of government spending (is it really consistent with your values that per capita spending is going to fall quite sharply?, would it prove politically sustainable? and so on).

But it is of almost no relevance to monetary policy. And omits really major bits of the fiscal story (on the spending side, all of transfers and finance costs, and all of the revenue side). Central banks should be mostly interested in shocks to the deficit/surplus outlook. But not, this year, it appears the RBNZ.

The Bank and the MPC seemed to minimise any story about the fiscal contribution to the outlook for inflation and monetary policy (you know, things like inflation still being outside the target range, even with a high OCR, for protracted periods. Those fiscal impulse charts/numbers don’t get a mention. But neither do simple stats like the fact that in December’s HYEFU, on then government plans, Treasury thought the OBEGAL deficit for 2023/24 would be 0.1% of GDP. By May’s Budget, government plans meant a forecast deficit that year of 1.8% of GDP. These are really big changes, playing down to near-invisibility by our supposedly non-partisan independent MPC.

It was all brought back to the front of mind last week when, out of the blue, this observation appeared in the OCR statement

Broader government spending is anticipated to decline in inflation-adjusted terms and in proportion to GDP.

If you relied on Reserve Bank commentary, you’d just never know that, in the period current monetary policy choices are directly affecting, discretionary fiscal policy choices (overall balance and all that) had added, quite considerably, to inflation pressures in this year’s Budget. It doesn’t take much to guess which line the Minister of Finance will have preferred – and it isn’t the one that actually aligns with the Bank’s own responsibilities.

I am really reluctant to believe that partisan positioning is at work, even if (if it is happening) “just” for institutional self-protection reasons. But I find it difficult to see a compelling alternative explanation for the MPC’s approach to fiscal analysis and fiscal impulses in the last couple of months.

Perhaps the Opposition parties will view the Reserve Bank more charitably. But on what has been put before us, there is no reason for them to do so.