The Reserve Bank is a powerful public agency, whose views receive a lot of coverage, and some respect in some quarters. The views taken by the Bank affect where interest rates are set, and thus the short-medium term path of the economy itself. They aren’t just commentators – they are players too – but they aren’t less than commentators. They use a lot of public money to undertake analysis that is supposed to underpin their commentary and decisions. It should be pretty much Open Government 101 that citizens – who pay for the analysis and are directly affected by how the Bank uses it – should be able to see that analysis. The Reserve Bank has never seen it that way. Over decades – when I was closely involved, and still now – they’ve taken the view that the Bank is different, and special, and that all we should be entitled to see is what they choose to tell us. Even Xi Jinping reaches that low bar.

Sadly, the Bank has had the Ombudsman – supposedly the watchdog for citizens to ensure, specifically, that the Official Information Act is complied with (in letter, but ideally also in spirit) – wrapped around its little finger for decades now. Through successive Chief Ombudsmen and successive Governors, the Ombudsman’s office has provided cover for one of the most powerful agencies of government, one still (for a few more months) run as one man’s fiefdom (single decisionmaker regime).

KiwiBuild is a case in point. As I noted, the Reserve Bank is a powerful public agency. KiwiBuild is a major element in the current government’s policy, and one very relevant to the Reserve Bank given the role fluctuations in residential investment often play in business cycles. What the Reserve Bank thinks about the impact of KiwiBuild matters for monetary policy. It can matter also to the government, especially now that its flagship programme appears to have run into political difficulties.

The Reserve Bank first opined on KiwiBuild in its November Monetary Policy Statement last year. That document was finalised shortly after the new government took office, and in it the Bank reported – in highly summary form – the assumptions it had made about four strands of the new government’s programme minimum wages, fiscal policy, immigration, and Kiwibuild). Here is what they had to say about KiwiBuild (emphasis added).

The Government has announced an intention to build 100,000 houses in the next decade. Our working assumption is that the programme gradually scales up over time to a pace of 10,000 houses per year by the end of the projection horizon. Given existing pressure on resources in the construction sector, the aggregate boost to construction activity from this policy will depend on how resources are allocated across public and private sector activities. The Government intends to introduce a ‘KiwiBuild visa’ to support the supply of labour to high-need constructionrelated trades. While accompanying policy initiatives may alleviate capacity constraints to some extent, our working assumption is that around half of the proposed increase will be offset by a reduction in private sector activity.

It wasn’t necessarily an unreasonable working assumption, but it was very early days for the new government. Presumably the Bank had had the benefit of perspectives from, say, MBIE and Treasury that the public were not privy to, and they must have applied their own (considerable) analytical resources to thinking hard about how, at any economywide level, crowding out would work. It didn’t seem unreasonable that if the central bank was going to weigh in like this, and make policy on the basis of such assumptions, we should be able to see a little more of their supporting analysis. After all, if the correct number wasn’t a 50 per cent crowding out, but (say) 25 per cent, 75 per cent or even 100 per cent, it could have material implications for monetary policy.

And so, a few days after the Monetary Policy Statement was released, I lodged a request for

copies of any analysis or other background papers prepared by Bank staff that were used in the formulation of the assumptions about the impact of four specific policies of the new government minimum wages, fiscal policy, immigration, and Kiwibuild), as published in the November 2017 Monetary Policy Statement.

Somewhat predictably, the Bank refused and I appealed the matter to the Ombudsman.

The Bank justified its refusal on two conventional grounds, and one on which the Ombudsman has never provided substantive guidance.

The Reserve Bank is withholding the information for the following reasons, and under the following provisions, of the Official Information Act (the OIA):

- section 9(2)(d) – to avoid prejudice to the substantial economic interests of New Zealand;

- section 9(2)(g)(i) – to maintain the effective conduct of public affairs through the free and frank expression of opinions by or between officers and employees of the Reserve Bank in the course of their duty; and

- section 9(2)(f)(iv) – to maintain the constitutional convention for the time being which protects the confidentiality of advice provided by officials.

Anyone with a modicum of interest in open government, and even the slightest familiarity with the Reserve Bank, financial markets etc, would recognise that the claim that releasing such background supporting analysis would prejudice the “substantial economic interests of New Zealand” is laughable.

The Reserve Bank continues to comment on KiwiBuild, and the implications of that programme for the overall outlook for residential investment and for economic activity. The views taken by the Bank still matter, both substantively (monetary policy) and in terms of the growing political controversy over the programme. And they continue to provide almost no substantive analytical underpinnings for their views. Here is the relevant extract from last week’s MPS.

The Government’s KiwiBuild programme is expected to contribute to residential investment over the second half of the projection.

and

The KiwiBuild programme is assumed to add to the rate of house building from the second half of 2019.

And that’s it. No description of any analysis they (presumably) must have undertaken.

The issue came out in the press conference, where it was even enough to win the government a favourable news story, Reserve Bank backs KiwiBuild targets… mostly. Here is some of that story

But the Reserve Bank’s quarterly Monetary Policy Statement noted that the “KiwiBuild programme is assumed to add to the rate of house building from the second half of 2019”.

That’s big news. The Bank puts extensive resourcing into coming up with its economic forecasts, and it’s essential that it does so. The Bank’s forecasts guide it’s setting of the official cash rate which is one of the main levers that sets the pace of the economy. Get it wrong, and the consequences can be severe.

That’s why it’s worth noting that the RBNZ now appears to back the view that most of the KiwiBuild homes built will be in addition to the current housing supply, which is roughly 30,000 houses delivered on the private market.

Critics have assumed that all or most of the 12,000 houses KiwiBuild will deliver each year, once fully deployed, will come by sucking resources from the 30,000 builds currently taking place. New Zealand will still build 30,000 houses a year, but 12,000 of them will be KiwiBuild, they say.

But the Bank disagrees, saying its forecasts have “assumed some minor set off”, but that KiwiBuild is overall likely to increase housing supply.

This is a change from the Bank’s MPS from last November. At the time, RNZ reported the Bank’s preliminary calculation was that as many as half of KiwiBuild’s projected 100,000 homes would have been built anyway.

Housing Minister Phil Twyford responded then that “there may be some offset but I doubt it will amount to very much”.

It now seems the Reserve Bank largely agrees, although as an independent entity it is duty bound to stay out of politics.

It doesn’t totally back the Government’s aspiration to deliver all the KiwiBuild homes in addition to existing supply.

Reserve Bank Chief Economist John McDermott said there would still likely be some “crowding out” as KiwiBuild sapped workers and resources from the private sector.

“You can imagine when one part of the economy starts to increase demand it will crowd out some other parts but overall we will start to see quite a lot of activity over the next few years in residential construction,” he said.

This stuff matters, Orr and McDermott are opining on it, Orr is making monetary policy on it, but they can’t or won’t supply any supporting analysis. Not a year ago, and not now. Perhaps they are right, but what confidence should we have in their views when they won’t show us, so to speak, their workings. Old exam question used to specify that if you wanted credit for your answer (to, say, some maths problem) you needed to show your workings. It isn’t obvious why the bar should be so much lower for a powerful public agency like the Reserve Bank.

Sadly, they have persuaded the Ombudsman to agree with them. In my post on Thursday, I included some text from a submission I had made a few months ago to the Ombudsman on his provisional determination on this issue. On Friday I received a letter from Peter Boshier, the chief ombudsman, conveying his final decision. In it, he fully backed the Reserve Bank’s stance of refusing to release any of the background papers.

In my submission I had attempted to draw a parallel between background papers provided to the Governor on matters relating to MPSs and OCR decisions, and material provided to the Minister of Finance in respect of, notably, the Budget. Each year a huge amount of that latter material is pro-actively released. I noted

Thus, Cabinet papers underpinning key government announcements are frequently released, sometimes in response to OIA requests and at other times pro-actively. But so too is advice to a Cabinet minister from his or her department. That is so even when, as is often the case, officials have a different view on some or all of the matters for decision from the stance taken by the minister. A classic example, of course, is the pro-active release of a great deal of background material, memos, aide-memoires etc compiled and submitted as part of the Budget formulation process. Many of the working papers in that case may never even have been seen the Secretary to the Treasury but will have been signed out to the office or minister at the level of perhaps a relatively junior manager. Many will have been done in a rush, and be at least as provisional as analysis the Governor receives in preparing for his OCR decision. I’ve been personally involved in both processes.

Is it sometimes awkward for the Minister of Finance that his own officials disagreed with some choice the minister made? No doubt. Do ministers sometimes feel called upon to justify their decisions, relative to that official alternative advice? No doubt. But it doesn’t stop either the provision of such dissenting (often quite provisional) analysis and advice, or the release of those background documents.

The sorts of arguments the Reserve Bank makes, and which Mr Boshier appears to have accepted, could well be advanced by Cabinet ministers (eg clear messaging about this or that aspect of budgetary or tax policy – all of which are substantial economic interests of the NZ government). If they have advanced such arguments, they have generally not succeeded. And nor should they. Doing so would undermine effective accountability or scrutiny, even though the Minister’s formal accountability might be to Parliament (he has to get his Budget passed).

The relationship between the Minister and his or her department officials is closely parallel to that between the Governor of the Reserve Bank – the sole legal decisionmaker (who doesn’t even have to get parliamentary approval of his decisions) – and the staff of (in this case) the Economics and Financial Markets departments of the Bank. One group are advisers, and the other individual is the decisionmaker. The fact that they happen to both part of the same organisation, doesn’t affect the substantive nature of that relationship. Managers and senior managers in the relevant departments are responsible for the quality of the advice given to the Governor, in much the same way that the Secretary is responsible for Treasury’s advice to minister (and at his discretion can allow lower level staff to provide analysis/advice directly to the Minister or his office) I would urge you to substantively reflect on the parallel before reaching your final decision, including reflecting on how (if at all) official advice on input to the OCR is different than official advice (including supporting analysis) on any other aspect of economic policy.

Remarkably, in his determination to protect the Reserve Bank, Boshier simply ignores the parallel to Treasury budget advice altogether. Perhaps it isn’t altogether the appropriate parallel (although I think the situations are extremely analagous), but instead of engaging and identifying relevant similarities and differences, the Chief Ombudsman simply ignores the argumentation. He seems to think it is okay for powerful public agencies to make policy based on critical assumptions, and opine on matters of political sensitivity, and yet to be under no obligation to show any of their workings, even when (as in this case) such material clearly exists (the responses make that clear).

If that weren’t bad enough, the Ombudsman plumbs new depths with this paragraph from his letter

You contend that the formal accountability of the Governor is relatively weak and that public scrutiny and challenge is the most effective form of accountability. However, that view would seem conflict with your previous stated view that it was the Reserve Bank Board, rather than market commentators, who was best placed to hold the Governor to account.2 Your paper makes a very strong case for the merits of the formal accountability mechanism, the disadvantages of market commentators, and the legitimate variance of views that can arise.

I was initially a bit puzzled about what he was going on about, until I looked at footnote 2. It was a link to this paper on monetary policy accountability and monitoring, which I had written for the Bank, as a Bank employee, in about 2005 or 2006, making a defensive descriptive case for the Bank, including highlighting how open and accountable it was. The article has actually been amended slightly in recent years, but even at the time it wasn’t my own view – it was the official Bank line. That is what public servants are paid to write. (Heck, I’ve given presentations making the case for OCR decisions I strongly disagreed with – it is what public servants do.) As I recall it, the article had been intended for publication in the Reserve Bank Bulletin, and my own bosses had been reasonably comfortable, but the Bank’s Board was most definitely not comfortable, and insisted both that it not appear in the Bulletin and that before it appeared anywhere it be amended to play up the importance of the Board’s monitoring and accountability (relative to the way things were presented in the draft).

I couldn’t believe that a serious person – and Peter Boshier used to be a senior judge, and as Ombudsman is entrusted by Parliament with protecting citizen’s interests – was actually going to run so feeble an argument. Perhaps it seemed like a “gotcha” argument to some junior person in his office, but review processes are supposed to winnow out such lines. I’m still sitting here shaking my head in disbelief. The Ombudsman seriously wants us to believe that because a Bank official, writing for the Bank – a decade or more ago – says it is highly accountable via the Board, it is in fact so. Only someone determined to provide cover for the Bank could even think to take such a line seriously. But that seems to be a description of the Ombudsman.

As tiny sliver of hope, the Ombudsman did point out that his decision had to be made as at the time I initially lodged the request, ie was it reasonable for the Bank to have withheld the information last November/December, a few weeks after the relevant MPS. As a year has now passed, I have submitted a new request to the Bank, for exactly the same information from last November. I fully expect the Bank to decline that request, and then the Ombudsman can determine whether even after a year citizens should be entitled to see the working analysis powerful public agencies use when they opine on, for example, controversial government policies. The Official Information Act is well overdue for an overhaul, but decisions like these simply reinforce the case, with more evidence of how ineffective the administration of the Act (including by the Ombudsman) often is in delivering on the purpose statement in the Act itself.

Meanwhile, Orr and McDermott opine on KiwiBuild and (apparently) make policy on their opinions, but refuse to provide anything of the analysis that underpins their views. That simply isn’t good enough.

ADDENDUM

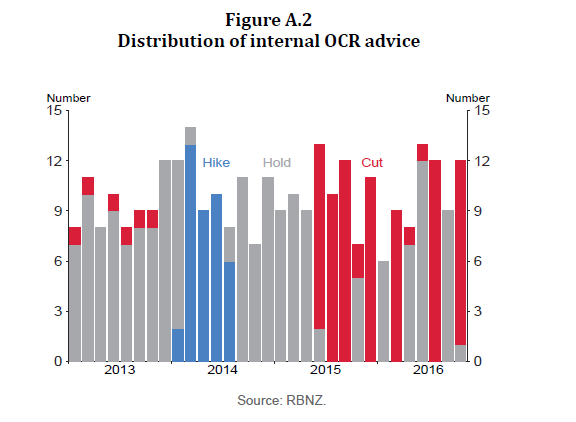

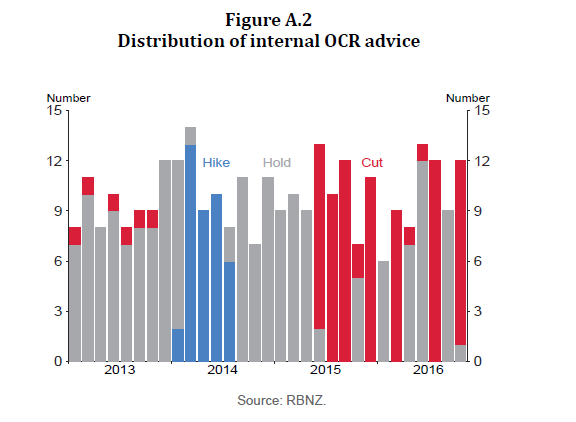

For anyone interested in another small example of how the Reserve Bank has the Ombudsman wrapped around their little finger, consider the release last Thursday in the Monetary Policy Statement of this chart.

When I’d first seen it I offered a little bit of praise to the Governor for publishing it. It happened to be quite similar to information I had requested more than 2.5 years ago, and which the Bank had refused to release.

As I noted in the post on Thursday, I learned a few minutes after publishing that praise of the Governor that, in fact, they had published the material only because – after a mere 2.5 years – the Ombudsman had got round to asking them to reconsider. But it got worse when I got the formal letter from the Ombudsman on Friday. They did actually apologise for taking 2.5 years and noted

As you may appreciate, this investigation has involved several meetings and much correspondence with the Reserve Bank concerning the use of a rarely-used withholding ground.

(From memory this is the “substantial economic interests” ground, which the Ombudsman thus again avoids formally ruling on.)

But this was the bit that really caught my eye

To preserve market neutrality, the Reserve Bank asked me not to inform you of its decision to release this information until after the November MPS.

This simply confirms that the Ombudsman and his staff have no concept of what might, or might not, be market sensitive. Anyone with the slightest familiarity with the issue will recognise what actually happened. The Bank decided to put the information in the MPS so that it might perhaps attract a little praise (for new interesting information) – and it even managed to get some from me – while avoiding a situation where, having released the information to me – me having requested it 2.5 years ago – I could have put it out first here, with some digs about the process, the obstruction, and the interests of transparency.

As it happens, I have no problem at all with the Bank putting the material in the MPS. It gave the material more visibility than it would get here – and there was even a question at the press conference – but no one, but no one (other than presumably the Ombudsman’s office, which appear not to know what it doesn’t know) would have bought the line about this old information being in any way market sensitive, or hence the alleged need for “market neutrality” about its release. The Ombudsman’s office, again, allowed itself to be used by the Bank. Relevant Bank staff will no doubt have been quite pleased with themselves. But if anyone from the Ombudsman’s office is reading this – and perhaps I’ll send them a copy – they might use it as a prompt to begin to rethink the extreme deference they’ve displayed towards the Bank over the years.