Regular readers will recall that I have, intermittently, been on the trail of the approach taken to the selection (and rejection) of external MPC members when the current crop were first appointed in 2019. I have been pursuing the matter since a highly credible person who was interested in being considered for appointment told me that (a) the Bank’s search company had informed my interlocutor that they would not be considered because they had active research expertise in areas around macroeconomics, and (b) having been somewhat puzzled by this response they had personally checked this understanding with the chair of the Reserve Bank’s Board, Neil Quigley, who had confirmed that was the policy. (The person concerned has never challenged my understanding of those conversations and has reiterated concerns over the years). OIAed documents from the Minister of Finance in mid-2019 confirmed that that approach had also been The Treasury’s understanding at the time (Treasury having responsibility for the ministerial/Cabinet side of the process); indeed that the Minister himself had endorsed/agreed to the ban.

I’m not going to repeat the entire subsequent chain. Everyone believed there had been such a blackball in place (it was even in an OIAed contemporaneous summary of a Board meeting discussion), and that included now-former senior central bankers (eg John McDermott) and the former economic adviser to Grant Robertson. These people may or may not have agreed with the ban, which the Minister himself and the Bank had defended on record in comments to media, but there was no doubt it had been there.

But then last year Quigley told Treasury that there had never been a restriction and Treasury - despite a bit of scepticism from a couple of senior officials – put out an official comment stating that there had never been a ban, and that the particular 2019 document from Treasury to the Minister was all a misunderstanding by another fairly senior Treasury figure (who had - conveniently - now left The Treasury, and whom they appeared never to have checked their new view with). More recently, a former Reserve Bank Board member - who had also been a member of the Board’s selection sub-committee in 2018 – confirmed to the Herald that there had been a ban of the sort generally understood (although his comments suggested Quigley may have conflated in his mind - years on – two quite separate sets of discussions).

The renewed interest last year prompted me to go back and check the OIA response the Reserve Bank itself had provided me in 2019 about the selection process for MPC members. They had then provided a lot of useful material, but it also became clear that they had chosen to exclude - and not to identify for withholding under specific OIA grounds - all dealings between the Board and management on the one hand and the Board’s search company (Ichor) on the other, even though it was pretty clear that any and all such material had been within the scope of the initial request (“all material relating to the Board’s selection and recommendation of potential MPC members”). This was pretty egregious conduct by the Bank: it is one thing to identify that things have been withheld, and to provide specific grounds, and another to just ignore a whole class of material and never bother mentioning it.

Anyway, I decided to lodge a new OIA, including explicitly highlighting that the material requesting should already have been covered by the 2019 request. My request (from 7 September) was as follows for:

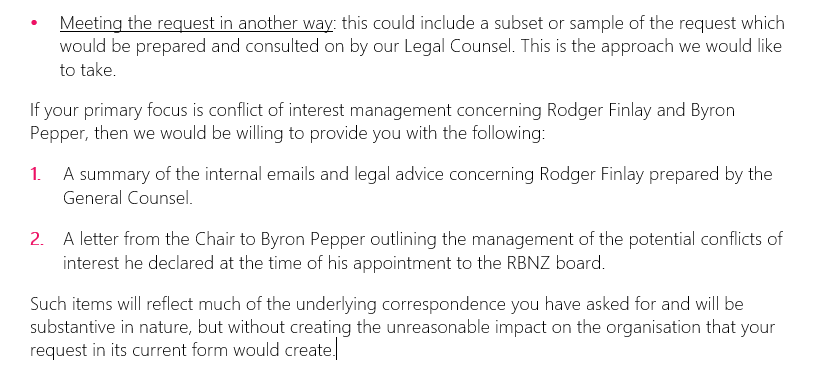

When the Bank’s response finally came back they explicitly identified 26 documents (all of which should have been covered by the 2019 request), and had explicitly evaluated each of them against the criteria in the Act, concluding that 17 could be released in full, 9 in part (mostly it appeared withholding names on privacy grounds, which - per my request - is just fine), and identifying no documents in scope that would be withheld altogether.

But, nonetheless, they were not going to send me the information, and instead wanted to charge me $786.60, citing “the amount of time required to process your request and the frequency of requests from you over the last three months”.

I was briefly tempted. I have had run-ins with the Reserve Bank over proposed charges previously (some years ago). Almost always in the cases I’m aware of (my own and some other people) their attempts to charge have been, pretty clearly, straight-out obstructionism, when the Bank would really prefer people did not see the documents they had no grounds to withhold.

In this case, the Bank told me it had taken 10 hours to process the request. At just over a day of one person’s time that doesn’t seem particularly unusual – or out of step with requests I and others have previously lodged with them – and there was never an attempt to invoke a common agency line (often used to justify extensions) about needing to search a particularly large or ill-defined body of material (this was a specific request about one search firm on one project in one few-month period, so it must have been very easy to quickly find anything in scope, and it was all several years old). Moreover, they had made no attempt to reach out to narrow down the scope of the request or to suggest ways which might limit the risk of charging - the sort of good faith steps they are required to do, if acting lawfully and in good faith.

Had I made a few requests in the previous few months? Yes, I had, including on matters around MPC appointments, and on the Reserve Bank’s puzzling treatment of fiscal policy issues. They were relevant issues to the scrutiny of a very powerful, but underperforming - and not straight with the public - public agency, whose Board chair had already pretty clearly been shown to have actively misled Treasury and, in turn, the public. (Oh, and one was a request for a specific 2016 document, that was about two pages long and not itself contentious or on matters of policy, for which I gave them the title, the author, the date, and the document number in their document management system - I already had a copy but wanted to be free to use it with another audience.)

I’ve been sitting on the Bank’s response for a couple of months - other stuff demanding my time and attention - not quite sure what to do. I’d be astonished if the Ombudsman did not uphold an appeal against the Bank’s attempt to charge for this request – but that might take two years – especially given that the material should have been included in a response to a request that the Bank had responded to (otherwise) appropriately in 2019, and is on a matter of significant interest to those attempting to monitor and hold the Bank to account (it was after all prompted ultimately by Quigley’s and Treasury’s egregious attempts to rewrite history - and if Quigley really was, after all, telling the truth, these documents should if released support his position: almost certainly they do not).

Just briefly, why do I say that they almost certainly do not? Among other things because in the material the Bank released to me in 2019 there was this email that I’ve included in previous posts on the MPC appointments issue (Mike Hannah then being the Secretary to the Board)

That said, since I have not lodged any OIA requests with the Bank for more than three months now, I am pondering resubmitting my request (it was, after all, them who cited as an excuse for attempting to charge a concentration of requests in a three-month period).

Alternatively, here is the full Bank response

RB OIA response re request for information on Ichor and the 2019 appointment of external MPC members

Anyone else could feel free to submit the request themselves (the exact words are in the document, as is the complete list of documents they had identified and already reviewed, so there will be almost zero marginal cost for them to handle such a request, and no legal basis for attempting to charge. If anyone else does choose to make the request, I’d be happy to hear/see the response in due course (mhreddell@gmail.com).

[UPDATE: The Bank’s contact email for OIA requests is rbnz-info@rbnz.govt.nz ]

As it is the clock is now ticking on the terms of two of the MPC members which expire (finally, with no possibility of reappointment) in the next few months. The documents released last year suggest there is no longer a bar on specialist expertise in external MPC appointments, although the suspicion remains that Orr and Quigley (and the tame underqualified Board) will instead have imposed a bar on anyone who might make life at all awkward for the Governor. To date, the new Minister of Finance has given no hint of reopening the application or selection process – despite it all having occurred under the previous government and its appointees – and I guess only time will tell whether she has been willing to go along with such a bar, which might be less visibly egregious, but no better in terms of building a strong and open MPC, the need for which is only made more evident by the deep failures of the current MPC under Orr in the almost five years since the current externals were appointed.