Monday’s post was on the important place effective accountability must have when government agencies are given great discretionary power which – as is in the nature of any human institutions – they will at times exercise poorly. My particular focus is on the Reserve Bank, both because it is what I know best, because it exercises a great deal of discretionary power affecting us all, and because in recent times it has done very poorly in multiple dimensions (be it bloated staffing, demonstrated loss of focus, massive financial losses, barefaced lies, or – most obvious to the public – core inflation persistently well above target).

What has happened under the current (outgoing) government is now an unfortunate series of bygones. What has happened, happened, and some combination of Orr, Robertson, Quigley (and lesser lights including MPC members and the Secretary to the Treasury) bear responsibility. Not one of them emerges with any credit as regards their Reserve Bank roles and responsibilities.

But in a couple of weeks we will have a new government, and almost certainly Nicola Willis will be Minister of Finance. The focus of this post is on what I think she and the new government should do, if they are at all serious about a much better, and better governed and run, institution in future. It builds on a post I wrote in mid 2022 after someone had sought some advice on a couple of specific points.

Thus far, we have heard very little from National on what plans they might have for the Reserve Bank. When they were consulted, as the law now requires, they opposed Orr’s reappointment (although on process grounds – wanting to make a permanent appointment after the election, something the legislation precluded – rather than explicitly substantive ones). And anyone who has watched FEC hearings over the past 18 months will have seen the somewhat testy relationship between Orr and Willis (responsibility for which clearly rests with Orr, the public servant, who in addition to his tone – dismissive and clearly uninterested in scrutiny – has at least once just lied or actively and deliberately misled in answer to one of Willis’s perfectly reasonable questions). In the Stuff finance debate last week I noticed that when invited to do so Willis avoided stating that she had confidence in Orr, but she has on a couple of occasions said that she will not seek to sack him, stating that she and he are both “professionals” (a description that, given Orr’s record, seems generous to say the least).

Even if she had wanted to, it would not be easy to sack Orr.

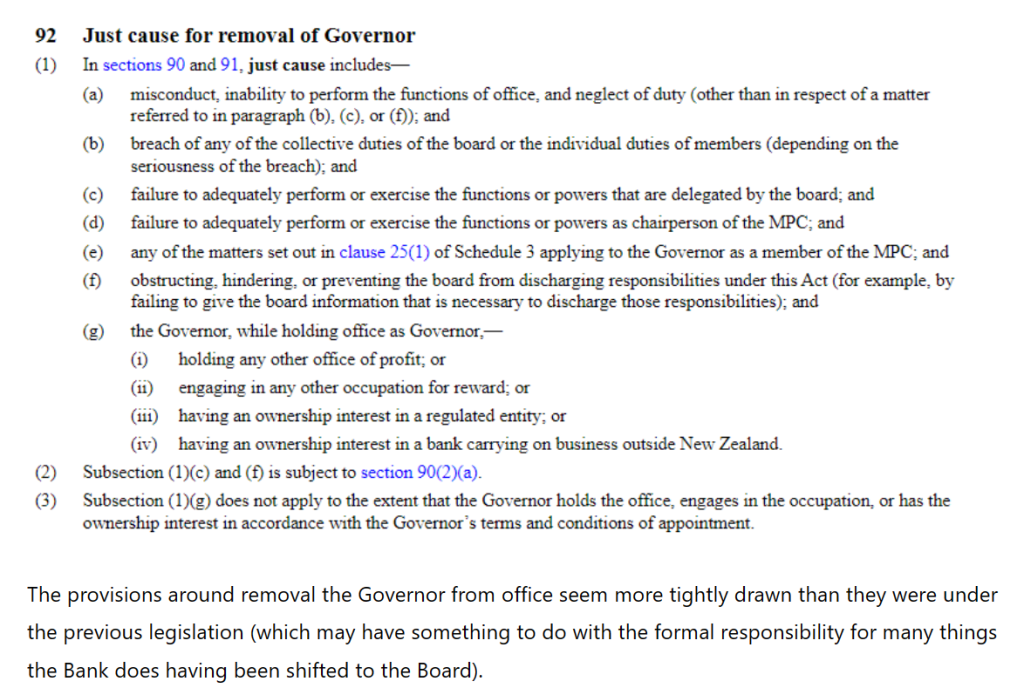

From last year’s post, these are the statutory grounds for removal

Note too that his current term in office started only in March this year, and the more egregious policy failures occurred in the previous term (and thus probably not grounds for removal now). I have my own list of clear failures even since March – no serious speeches, no serious scrutiny, no serious research, actively misleading Parliament, and so on – such that it would be much better if Orr were gone but seeking to remove him using these provisions would not be seriously viable, including because any attempt to remove him could result in judicial review proceedings, leaving huge market uncertainty for weeks or months.

Were the Governor an honourable figure he would now give six months notice, recognising that the incoming parties do not have confidence in him and that – whatever his own view of his own merits – it actually matters that the head of an agency wielding so much discretionary power should have cross-party confidence and respect (which does NOT mean agreeing with absolutely everything someone does in office).

Historically (and even when I wrote that post 18 months ago) I would have defended fairly staunchly the idea that incoming governments should not simply be able to replace the central bank Governor. The basic idea behind long terms for central bank Governors was so that governments couldn’t put their hand on the scales and influence monetary policy by threat of dismissal. But many of those conceptions date from the days before the modern conception of the government itself setting an inflation target and the central bank being primarily an agency implementing policy in pursuit of that objective. Even when the Reserve Bank of New Zealand legislation was first overhauled in 1989 the conception was that Policy Targets Agreements should be set and unchanged for five year terms, beyond any single electoral term. That (legislated) conception never survived the first election after the Act was passed, but these days the legislation is quite clear that the Minister of Finance can reset the inflation target any time s/he chooses (there are some consultation requirements). If the government can reset the target any time they choose, then it isn’t obvious that they shouldn’t be able to replace the key decision-makers easily (when the key decisionmakers – specifically the Governor – have influence, for good and ill, much more broadly than just around pursuit of the inflation target).

(There is a parallel issue around the question of whether we should move to the Australian system where heads of government departments can be replaced more easily, but here I’m focused only on the Reserve Bank, which exercises a great deal of discretionary policy power, and isn’t just an advice or implementation entity.)

By law they can’t make such changes at present. They could, of course, amend the law, but to do so in a way narrowly focused on Orr (ie an amendment deeming the appointment of the current Governor as at the passage of this amendment to be terminated with effect six months from the date of the Royal Assent) would smack rather of a bill of attainder. Governors have been ousted this way in other countries, but I don’t think it is a path we should go down.

Some will also argue that Orr should simply be bought out. If the government was seriously willing to do that – and pay the headline price of having written a multi-million-dollar cheque to (as it would be put) “reward failure” – I wouldn’t object, but it isn’t an option I’d champion either. (Apart from anything else, a stubborn incumbent could always refuse an offer, and once this option was opened up there really is no going back.)

So the starting point – which Willis has probably recognised – is that unless Orr offers to go they are stuck with him for the time being.

The same probably goes for the MPC members and the members of the Bank’s Board. The incoming Minister of Finance could, however, remove the chair of the Board from his chairmanship (this is not subject to a “just cause” test). The current chair’s Board term expires on 30 June next year, and it might not be thought worth doing anything about him now, except that he is on record as having actively misled Treasury (and through them the public) about the Board’s previous ban on experts being appointed to the MPC, and he has been responsible for (not) holding the Governor to account for the Bank’s failures in recent years. Removing Quigley would be one possible mark of seriousness by a new government, and a clear signal to management and Board that a new government wanted things to be different in future.

The current Reserve Bank Board was appointed entirely by Grant Robertson when the new legislation came into effect last year. It was clearly appointed more with diversity considerations in mind than with a focus on central banking excellence, and several members were caught up in conflict of interest issues. The appointments were for staggered terms but – Quigley aside – the first set of vacancies don’t arise until mid 2025. It would seem not unreasonable for a new Minister to invite at least some of the hacks and token appointees to resign.

There are three external appointees to the Monetary Policy Committee. None has covered themselves in any glory or represented an adornment to the Committee or monetary policymaking in New Zealand. All three have (final) terms that expire in the next 18 months, two (Harris and Saunders) in the first half of next year. This is perhaps the easiest opportunity open to a new Minister to begin to reshape the institution, at least on the monetary policy side, because appointments simply have to be made in the next few months. As I noted in a post a couple of weeks ago, OIAed documents show that the current Board’s process for recommending replacements is already largely completed, with the intention that once a new government is sworn in they will wheel up a list of recommendations. If the new government is at all serious about change, this should be treated as unacceptable, and the new Minister should tell the Board to rip up the work done so far and start from scratch, having outlined her priorities for the sort of people she would want on the MPC (eg expert, open, willing and able to challenge Orr etc). It would also be an opportunity for her to revisit the MPC charter, ideally to make it clear that individual MPC members are expected to be accountable for, and to explain, their individual views and analysis. Were she interested in change, it is likely that the pool of potentially suitable applicants might be rather different than those who might have applied – perhaps to be rejected as uncomfortable for Orr at the pre-screening – under the previous regime.

The Reserve Bank operates under a (flawed) statutory model where a Funding Agreement with the Minister governs their spending for, in principle, five years at a time. The current Agreement – recently amended (generously) with no serious scrutiny, including none at all by Parliament – runs to June 2025. The incoming government parties have been strong on the need to cut public spending by public agencies on things that do not face the public. They need to be signalling to the Reserve Bank that they are not exempt from that approach, and if the current Funding Agreement cannot be changed it should be made clear to the Board and management that there will be much lower levels of funding from July 2025. Indulging the Governor’s personal ideological whims or inclinations to corporate bloat are not legitimate uses of public money.

If she is serious about change, the incoming Minister also shouldn’t lose the opportunity to deploy weaker but symbolic tools at her disposal. Letters of expectation to the Governor/MPC and the Board can make clear the direction a new government is looking for, as can the Minister’s comments on the Bank’s proposed Statement of Intent. Treasury now has a more-formal role in monitoring the Bank’s performance, and the Minister should make clear to Treasury that she expects serious, vigorous and rigorous, review.

All this assumes the incoming Minister is serious about a leaner, better, more-excellent and focused Reserve Bank. If she is, and is willing to use the tools and appointments at her disposal, she can put a lot of pressure on Orr. If that were to lead to him concluding that it wasn’t really worth sticking around for another 4.5 years that would be a good outcome. But at worst, he would be somewhat more tightly constrained.

I haven’t so far touched on the two specific promises National have made. The first is to revise the legislation (and Remit) to revert to a single statutory focus for monetary policy on price stability. I don’t really support this change – the reason we have discretionary monetary policy is for macro stabilisation subject to keeping inflation in check – but I’m not going to strongly oppose it either. The 2019 change made no material difference to policy – mistakes were ones of forecasting (and perhaps limited interest and inattention thrown in) – and neither would reversing it. Both are matters of product differentiation in the political market rather than a point of policy substance. The proposed change back risks being a substitute for focusing on the things that might make for an excellent central bank – as it was with Robertson. I hope not.

The other specific promise has been of an independent expert review of the Bank’s Covid-era policymaking. It isn’t that I’m opposed to it – and there is no doubt the Bank’s own self-review last year was pretty once-over-lightly and self-exonerating – but I’m also not quite sure what the point is, other than being seen to have done it. Action, and a reorientation of the institution and people, needs to start now, not months down the track when some independent reviewer might have reported (and everyone recognises that who is chosen to do the review will largely pre-determine the thrust of the resulting report). It isn’t impossible that some useful suggestions might come out of such a report, but it doesn’t seem as though it should be a top priority, unless appearance of action/interest is more important than actual change. I hope that isn’t so either.

What of the longer term, including things that might require more-complex legislative change?

I think there are number worth considering, including:

- how the MPC itself is configured. I strongly favour a model – as in the UK, the US, and Sweden – in which all MPC members are expected to be individually accountable for their views, and should be expected routinely to record votes (and from time to time make speeches, give interviews, appear before FEC). I’m less convinced now than I once was that the part-time externals model can work excellently in the long haul, even with a different – much more open, much more analytically-leading – Governor. One problem is the time commitment, which falls betwixt and between. External MPC members have been being paid for about 50 days a year, which works just fine for people who are retired or semi-retired, but doesn’t really encourage excellent people in the prime of life to put themselves forward (I’m not sure how even university academics – with a fulltime job – can devote 50 days to the role). In the US and Sweden all MPC members are fulltime appointments, and in the UK while the appointments are half-time they seem to be paid at a rate that would enable, say, an academic to live on the appointment, perhaps supplemented with some other part-time (non-conflicted roles). I also used to put more weight on the idea of a majority of externals, which I now think is a less tenable option than I once did. External members can and should act as something of a check on and challenge to management, but it will always be even more important to have the core institution functioning excellently (at senior and junior levels). We should not have a central bank deputy chief executive responsible for matters macroeconomic who simply has no expertise and experience, and is unsuited to be on any professional MPC.

- I would also favour (and long have favoured) moving away from the current model in which the Board controls which names go to the Minister of Finance for MPC and Governor appointments. It is a fundamentally anti-democratic system (in a way with no redeeming merits), and out of step with the way things are done in most countries. We don’t want partisan hacks appointed to these roles, but the Board – itself appointed by (past) ministers – is little or no protection, and Board members in our system have mostly had little or no relevant expertise. Appointments should be made by the Minister – in the case of the Governor, perhaps with Opposition consultation – and public/political scrutiny should be the protection we look to. I would also favour all appointees to key central bank roles have FEC scrutiny – NOT confirmation- hearings before taking up their roles (as is done in the UK).

- I would also favour (as I argued here a few years ago [UPDATE eg in this post]) looking again at splitting the Reserve Bank, along Australian lines, such that we would have a central bank with responsibility for monetary policy and macro matters and a prudential regulatory agency responsible for the (now extensive) supervisory functions. They are two very different roles, requiring different sets of skills from key senior managers and governance and decision-making bodies. Accountability would also be a little clearer if each institution was responsible for exercising discretion in a narrower range of area. Quite obviously, the two institutions would need to work closely together in some (limited) areas, but that is no different than (say) the expectation that the Reserve Bank and Treasury work effectively together in some areas. (Reform in this area might also have the incidental advantage of disestabishing the current Governor’s job). Reform along these lines would leave two institutions with two boards each responsible for policymaking (and everything else) the institutions had statutory responsibility for. The current vogue globally has been for something like having a Board and an MPC in a single institution, the former monitoring the latter. But the New Zealand experience in recent years is illustrative of just how flawed such a model is in practice: not only is the Board still within the same institution (thus all the incentives are against tough challenge and scrutiny) but typically Reserve Bank Board members have no relevant expertise to evaluate macro policy performance or key appointments in that area). Monitoring and review matter but if they are to be done well they will rarely be done within the same institution with (as here) the chair of the MPC (Orr) sitting on the monitoring board. The new Board’s first Annual Report last week illustrates just how lacking the current system is in practice, and although a new minister might appoint better people, we should be looking to a more resilient structure.

As I said at the start of this post we – public, voters, RB watchers – really don’t have much sense of what National or Willis might be thinking as regards the Reserve Bank. I tend to be a bit sceptical that they care much, but would really like to be proved wrong. There are significant opportunities for change, which could give us a leaner, better, much more respected, central bank. It is unfortunate that these matters need to be revisited so soon after the legislative reforms put in place by the previous government, but they do – we need better people soon, but also need some further legislative change.

UPDATE: A conversation this afternoon reminded me of the other possible option for getting Orr out of the Reserve Bank role: finding him another job. There might not be many suitable jobs the new government would want someone like Orr in, but I have previously suggested that something like High Commissioner to the Cook Islands might be one (having regard to his part Cooks ancestry, and apparent active involvement in some Pacific causes). More creative people than me may have other (practical) suggestions.

This comment isn’t related to this specific post but I’m a traditionally centre left voter who has been quite disappointed by the lack of delivery and broken promises from Labour regarding things I care about (strengthening Kiwisaver, actual public transport infrastructure etc) and was going to be unhappy regardless of who formed govt.

All this to say that I am diametrically opposed to a lot of views expressed on this blog but I still enjoy reading this for how much I have learned. Your focus on productivity encouraged me to vote for TOP as I believe their policies are best placed to tackle the problem while fitting my world view.

Thanks once again for all the analysis and data you provide.

LikeLike

Thanks

LikeLike

“Give me control of a nation’s money supply, and I care not who makes its laws.”

I appreciate your skepticism of the Reserve Bank.

I believe most of our policies come top down from the “central banksters” .

Not many bloggers are seeing with central banking and taking private loans with interest for things like infrastructure we have a foreign economic monopoly .

LikeLike

[…] What should be done about the Reserve Bank? […]

LikeLike