Over the course of the last week, I’ve noticed a couple of interesting polls on attitudes to (some aspects of) immigration.

First was a note by Katharine Betts, for The Australian Population Research Institute, drawing on data from the 2016 Australian Election Survey. Two of the questions asked were

A1: ‘Do you think the number of immigrants allowed into Australia nowadays should be reduced or increased?’

A2: ‘The number of migrants allowed into Australia at the present time has: gone much too far, too far, is about right, not gone far enough, not gone nearly far enough’

And one of the very interesting aspects of the survey is that election candidates were asked the same questions as general (voter) respondents.

Recall, too, that the target level of non-citizen immigration to Australia was increased a lot about a decade ago, and is now similar to – just a little less than – New Zealand, in per capita terms.

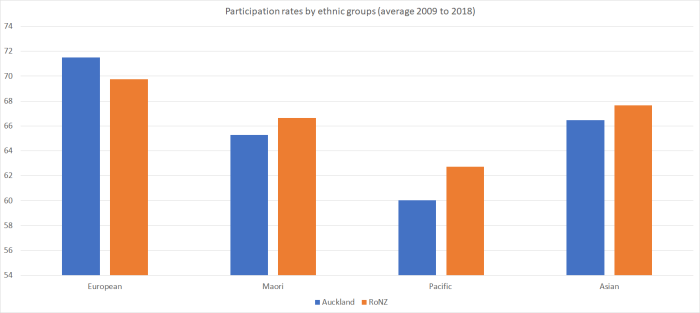

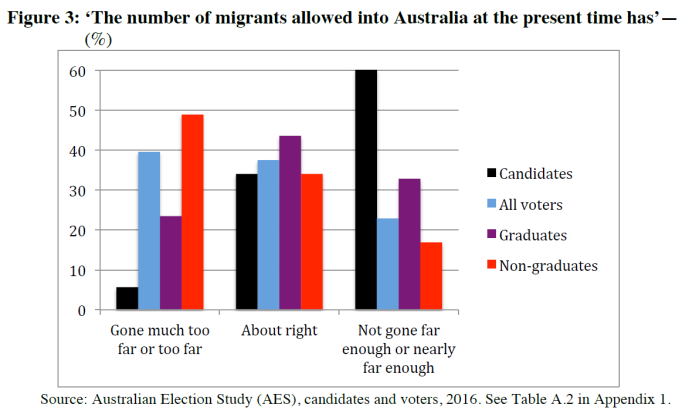

Here is a chart of the summary responses to that second question.

Among all voters, more think things have gone too far than think there hasn’t been enough migration. On the other hand, a majority favour either keeping things at the current high level or increasing immigration further (the results are similar for the first question, the wording of which is more explicitly flow-based).

But what is most striking is the contrast in views between voters and candidates. 60 per cent of candidates favoured further increasing Australia’s rate of immigration while only 6 per cent favoured a reduction (a net 54 per cent favouring an increase). By party, that result is massively dominated by Labor and Greens candidates, with Coalition candidates more evenly divided. By contrast, among voters a net 17 per cent favoured a reduction, and among non-graduates a net 32 per cent favoured a reduction.

It will be interesting to see the results of any immigration questions in the New Zealand 2017 Election Survey, including the results by party. In last year’s election, two of our now governing parties campaigned on policies intended to have the effect of reducing immigration (one half-heartedly, and one not very specifically).

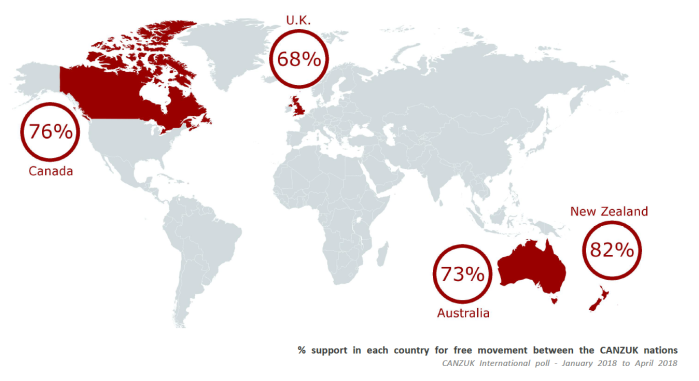

The other poll results were from the UK-based CANZUK International, which has been calling for free movement between Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the UK. In New Zealand, some pro-immigration advocates – including ACT’s David Seymour – have been championing the cause (and I noticed these results thanks to Eric Crampton of the New Zealand Initiative).

This was the question posed in New Zealand (country names re-organised according to which country is being polled)

“At present,citizens of the European Union have the right to live and work freely in other European Union countries. Would you support or oppose similar rights for New Zealand citizens to live and work in Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom, with citizens of Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom granted reciprocal rights to live and work in New Zealand?”

And this is their summary graphic.

Pretty overwhelming support in all four countries (at least as the question is worded). Interestingly, support is strongest in New Zealand – perhaps because New Zealanders have been the biggest beneficiaries in recent decades of freedom to go to another of these countries (Australia)?

I’ve never been quite sure what to make of the CANZUK cause. I read a lot of imperial/Commonwealth history, and ideas like this sort of free movement area among the old ‘white Dominions’ are strikingly reminiscent of calls for an imperial federation or, much later, for imperial trade preferences (which became a big thing as the UK moved away from free trade itself). I could be a little provocative and suggest that is wasn’t entirely dissimilar to the sort of immigration policies New Zealand and Australia ran until a few decades ago, that could be – not entirely inaccurately – characterised as “white Australia” or “white New Zealand” policies. In that sense, I’ve always been a bit puzzled by Eric Crampton’s enthusiasm for this particular formulation, when he is so ready to characterise sceptics or opponents of New Zealand’s current immigration policy as “xenophobes”. The logic of his position looks as though it should favour open borders more generally, not just among these four advanced, fairly culturally similar, countries. And yet, for example, even as an example of Commonwealth sentiment, not even South Africa – let alone Zimbabwe, Kenya or Namibia – appears in the CANZUK proposal.

Of course, there is a pretty straightforward answer. Almost invariably, public opinion in almost any country is going to be more open to large scale (or at least unrestricted) migration when it involves culturally similar countries than when it involves culturally dissimilar ones. In fact, there are good arguments that, if there are gains from immigration they could be greatest from people with similar backgrounds (and of course counter-arguments to that). Reframe the question as “would you support reciprocal work and residence rights among New Zealand, France, Belgium and Italy?”, and I suspect the support found in the CANZUK poll would drop pretty substantially – my pick would be something no higher than 50 per cent. Reframe it again to this time include Costa Rica, Iran, and Ecuador (let alone Bangladesh, India, and China – three very large, quite poor, countries) and people will start looking at you oddly, and the numbers will drop rapidly towards the total ACT Party vote (less than 1 per cent from memory).

And thus my own ambivalence about the CANZUK proposition. If I were a Canadian (of otherwise similar Anglo background to my own) I’d say yes. The historical and sentimental ties across these four countries – less so Canada – mean something to me. I’d probably even add the US into the mix. And across Australia, Canada, and the UK incomes and productivity levels are pretty similar – although the prediction would still presumably be that there would be an increased net flow of people from the UK to Australia (in particular) and Canada. As it is, I’ve repeatedly noted that my economics of immigration argument doesn’t distinguish between whether the migrants come from Birmingham, Brisbane, Bangalore, Buenos Aires, or Beijing. We’ve made life tougher (poorer, less productive) for ourselves by the repeated waves of migrants since World War Two – in the early decades, predominantly from the UK, and in the last quarter century more evenly spread. Even though we are now materially poorer than the UK, enough people from the UK still regard New Zealand as attractive, that free movement – the CANZUK proposition – would probably see a big increase in the number of Brits moving here (big by our standards, not theirs). That might be good for them – that’s up to them – but wouldn’t be good for us. Perhaps the effect would be outweighed by more New Zealanders moving to the UK long-term, but I’d be surprised if that were so.

The CANZUK proposition is an interesting one, and is worth further debate. Apart from anything else, it might tease out what people think about nationhood, identity, and some of the non-economic factors around immigration (including some of those Wilson and Fry suggest). As I noted, at present public opinion appears to be strongly in favour, but on the specific question asked in isolation. It would be interesting to know, if at all, how responses would change if the option was free CANZUK movement on top of existing immigration policy, or (to the extent of the new CANZUK net flow) in partial substitution for existing immigration policy. The two might have quite different economic and social implications.

Finally, on immigration-related issues, I recorded an interview yesterday with Wallace Chapman for broadcast on tomorrow’s Sunday Morning programme on Radio New Zealand. It was prompted by a lecture I’m giving this week for Presbyterian Support Northern in their series on different angles on responding to (child) poverty – mine being a focus on productivity. My focus in the lecture isn’t on specific solutions, but rather on the need to make lifting productivity a top national economic priority, since in the longer-term productivity is the only secure foundation for much higher material living standards. I’ll put up the text of my lecture here later next week, but the interviewer was more interested in possible specific solutions and thus quite a bit of our discussion was around immigration policy issues. Not thinking very fast on my feet that day, I forgot to respond to his suggestion that higher minimum wages might be part of the productivity answer by noting that we already have one of the highest ratios of minimum wages to median wages anywhere…….and one of the worst productivity records over many decades. Whatever the case for some mimimum wage, raising it is not part of the overall answer to fixing our productivity failures.