I mentioned yesterday that the New Zealand Initiative had released its Manifesto 2017: What the next New Zealand government should do. When I sat down and read it I came away with mixed feelings. There are quite of lot of specifics I agree with, which shouldn’t be a surprise: the Initiative is variously described as pro-business, neo-liberal (both, for different reasons, unhelpful descriptions – they are generally pro-market rather than pro-business) or just plain “right wing”. And I was summed up a few weeks ago by one journalist as being on the ‘dryish right of the spectrum’, which sounded roughly correct. We have our (large) differences over New Zealand immigration policy, and I’m a conservative while they often tend towards a libertarian view of the world, but there is often a lot of overlap in the sorts of policies we would favour. In fact in some areas I think they are far too trusting of central and local government.

I said I had mixed feelings. That is mostly because of the elephant in the room which in the Manifesto they almost entirely ignore – our long-term economic underperformance. The author – Initiative director Oliver Hartwich – is a recent migrant, clearly enraptured by New Zealand. That’s nice, but it rather ignores the things – the underperformance – that has led to such a large exodus of New Zealanders over the last 40 years or so. The relentlessly upbeat tone often comes across as almost delusional – which isn’t a good start to what he claims is “more than a collection of randomly assembled policies – it is an intellectual guide for imminent challenges”.

But what do they propose – drawing on many of the studies they have put out over their first five years of operation? As another (interesting – left wing) commentary on the Manifesto noted it is all “divided handily into six different sections and 28 different proposals”.

The first set are about housing

• abolish all rural-urban boundaries;

• abolish all height and density controls;

• strengthen property rights by introducing a presumption in

favour of development into the Resource Management Act;

• incentivise councils for development by letting them capture

the GST component of new buildings; and

• introduce MUDs but ideally give them a more appealing name

(maybe Community Development Districts).

I’m sympathetic to the broad direction of what they propose, but

- I don’t agree with abolishing all height and density controls on existing urban land (as distinct from newly developed land). Were it not for council rules, private landowners would in many cases have negotiated such restrictions themselves (as we see in the covenants in many new subdivisions) – waiving or trading them as and when mutually beneficial opportunities arose. My preference would be to devolve most existing restrictions to groups of existing landowners, and allow them to transact among themselves to permit (or not) greater height and density.

- I’m very sceptical of the Initiative’s support for disbursing GST revenue to local authorities. It seems like an opportunistic response to current pressures, which would quite dramatically overturn the sort of fiscal arrangements we’ve had since 1876 (and the end of provincial governments). Local authorites have their own revenue base – one generally favoured by economists as, in principle, less distortionary than most – and I’m not aware of provisions preventing differential rates.

The second set of recommendations is around education

• create an attractive career structure for teachers;

• provide tailored professional development for teachers;

• monitor teacher performance and introduce performance based

appraisals;

• evaluate systematically the impact of interventions on

school performance; and

• expand school clusters as a means of sharing best practice.

I haven’t read all their material on education, so perhaps I’ve missed something. The general direction seems fine, but this is one of those areas where they seem to be too ready to trust governments to get things right. I imagine that in the Business Roundtable days there would have been a lot more talk about genuine school choice – not just a few charter schools for targeted groups at the bottom, but much more genuine choice (public vs private, religious vs secular, non-profit vs for-profit etc) of provider for all parents, including greater choice about what is taught I probably shouldn’t be surprised, but as I’ve listened to my children over the years I’ve been surprised at just how much ‘indoctrination’ – of conventional left-wing/’progressive’ causes – goes on in our state schools; some of it conscious, much of it no doubt unconscious. The Initiative seems more focused on making the state behemoth work better – not necessarily a poor goal in its own limited way – rather than backing what I’d have thought would be a belief in markets, civil society etc.

Then they move on to foreign direct investment (where Bryce Wilkinson did some really useful work over several reports). Here they recommend

• Abolish the Overseas Investment Act. There should be no

FDI regime.

• Subject all investors, domestic and foreign, to the same rules.

• Protect New Zealanders’ property rights, including the

freedom to sell to whoever they wish. In cases of public

interest, appropriate compensation must be made.

I’d mostly agree with them, with four caveats:

- having gone to great lengths over the years to put in place good governance arrangements for our own SOEs, and in many cases to privatise them, I’m much less relaxed than the Initiative seems to be about allowing foreign SOEs – particular those from countries with, shall we say, weak governance traditions – to take on substantial roles in New Zealand. We might not suffer the poor returns to capital, but we still face potential efficiency losses. I have a strong prior that genuine private sector entities investing here will, on average, be mutually beneficial. One can’t extend the same presumption to organs of foreign states.

- in certain extreme circumstances – but they are extreme and rare – I’d be uneasy about allowing concentrated foreign ownership of New Zealand land. Had the Soviet Union during the Cold War wanted to buy up, say, most of Northland, it would have been dangerous and reckless to agree. It is fine to counter with “but the land is still New Zealand, subject to New Zealand law”. But one has to have the capacity to enforce that law. Geopolitical threats are, at times, real. My own halfway house would be to abolish controls on any investments from OECD member countries, and add to that list on a case-by-case basis.

- while I largely agree with the Initiative on FDI, I suspect it is a less important issue (in terms of potential economic gains) than they do. Why? Because the restrictions seem to bear most heavily on land purchases (not the sort of high-tech industries often touted as the way of the future – or even banks or oil explorers), and we already put so many other restrictions on land use (eg restrictions on GE products) that I’m sceptical that there is currently much in the economic case for liberalising foreign land purchases.

- I’m not totally averse to restrictions on non-resident foreigners purchasing residential properties in New Zealand – at least as some sort of third best, if governments can’t/won’t fix up land supply issues or the (aggravating) population pressures.

The next section is about better regulation (or better law). They propose

• No new law or regulation shall be introduced without a

cost-benefit assessment that demonstrates real gains for the

public and costs fairly shared.

• Regulatory reform cannot be delegated to a junior minister

but needs real commitment from the prime minister down.

• The regulatory culture should shift from one of ticking

boxes and managing risk to encouraging greater flexibility

and innovation.

and they repeat a line from a previous report

Over-reliance on primary legislation: New Zealand’s overreliance

on primary legislation is unusual by international

standards. Other countries use more secondary and

tertiary legislation to amend outdated rules. Most

regulatory changes in New Zealand require amendments

only Parliament can make.

In general, I’m sympathetic to the direction they propose, but

- I’m all for good cost-benefit assessments, but am less convinced of the argument that it should have to be demonstrated that “costs are fairly shared”. After all, it is rare legislation (primary or otherwise) that affects most people equally, and part of politics is differences in views of what is “fair”,

- Is anyone in favour of “tick boxes” approaches? I doubt it, although actual regulation often drifts towards that sort of outcome. Flexibility and innovation are laudable goals, but so is predictability and certainty when citizens are dealing with the state,

- I strongly disagree with them when they want to reduce reliance on primary legislation. For too much law-making power is already delegated by Parliament to ministers and official agencies. It is a technocrat’s dream, but a citizen’s nightmare.

They then move on to social policy

• Social policy is not a silo and should be regarded as a whole-of-

government task.

• Fixing New Zealand’s housing affordability crisis is crucial

to addressing both income-related poverty measures and

inequality concerns.

• To provide all New Zealanders with good life opportunities,

special attention needs to be paid to education. More

targeted support for students from lower deciles should take

precedence over untargeted programmes such as interest-free

student loans.

• Taxes and regulations should not choke off employers’

incentive to create jobs for the available skills or deprive

those with those skills of the incentive to work.

• The government’s plan to trial new ways of delivering social

services such as social bonds is laudable.

My thoughts?

- I’m rather sceptical – but open to persuasion – on the merits of “social bonds”.

- I’m more than sceptical of the big-government first bullet. The logic sounds compelling at first blush – and if fiscal savings were the only focus it might be persuasive – but it is a path that undermines privacy and autonomy, delivering more and more information to an overweening state.

- It is striking how the Initiative – like the government, and no doubt the Opposition – are reluctant to ever go near the role public policies have played in corroding cultures and giving rise to the welfare-dependency and other social problems joined-up government is now supposed to be trusted to deal with.

And then they turn to local government

• Local communities should share the benefits that accrue

to central government from extractive industries and

growth. Local government should receive financial benefits

for creating economic growth (and suffer a loss when it

does not).

• Central and local government need to better define their

responsibilities to preclude cost-shifting and blame games,

and enhance accountability.

• Special economic zones would increase flexibility and

regional variability of economic policy.

Here I largely disagree with them (and probably side more with the former Business Roundtable, which favoured restricting more tightly the activities of local government).

- the second bullet is vacuous. It is what politics is.

- I documented my scepticism about their special economic zones idea in a post in 2015.

- For all their talk of how many local authorities France or Germany have, it is worth remembering that this country has a total population not much different from that of a typical US state. Do we really think we have the policy capability for dozens of different economic policies? And what do we make of the demonstrated capability of local bodies? I know the Wellington City Council is one of the members of the Initiative, so perhaps they have to be polite, but it is a local body that hankers after uneconomic runway extensions, expensive convention centres and film museums, extraordinarily expensive town hall refurbishments, all while then going to cap in hand to government to sort out the water supply risks in an earthquake (a fairly basic function I’d have thought) I simply don’t understand why the Initiative wants to give more scope to local bodies. Perhaps it worked in Germany, but there is little sign it does here.

- I was also a bit flabbergasted when the Initiative seemed to lament local council reliance of property taxes. Local body rates aren’t a pure land tax, but they are probably further towards the non-distortionary end of the spectrum than most other possible taxes.

Their final section is about economic growth. There is plenty to agree with them on there.

Imagine if we could achieve an annual productivity

growth of 2% per year from now until 2060 instead of, say,

1.5%. Half a percent may not sound much. But through the

power of compound growth, it makes a substantial difference

to economic output.

By 2060, GDP per capita would be 22% higher (or about

$22,000 per person in today’s dollars) if we achieved 2%

productivity growth instead of 1.5%. ……

Creating a dynamic, growing economy is essential if we do

not want to end up like some European countries that have not

generated enough growth over the past decades, and are now

paying a heavy social and economic price for it.

All good stuff, but…….there is not a single policy recommendation in this section of the Manifesto. Not one.

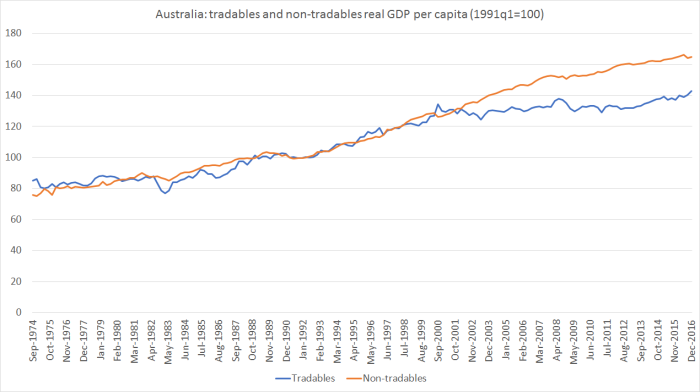

I suppose their defence will be that the earlier report they were drawing from was about making the case for economic growth, as against those who doubt it is something worth focusing on. But this is a policy manifesto, you are an (economics-based) think tank, and you have nothing specific to offer on diagnosing the causes of New Zealand’s disappointing long-term economic performance, and nothing on remedying it. It seems quite a large gap in the manifesto. No doubt, the Initiative would argue – and fairly – that some of their other proposals would lift productivity and per capita GDP, but I doubt any serious observer would think that list – even if all the items on it were adopted – would be more than modestly helpful in reversing our decline. After all, we did much more ambitious reforms – in the same general spirit – in the 1980s and early 1990s and they didn’t. (And for those about to comment “so what would you do”, I dealt with a list of things I’d favour in a post last year.)

Various omissions from the Manifesto struck me. Having just launched a major report on immigration, it was surprising to see almost nothing on that topic, not even on ways to improve the current system. Writing about the Manifesto at Spinoff, Simon Wilson noted

Still, I’ll give them this: they don’t believe cutting taxes is the cure for all ills and they don’t bang that old privatisation drum much either. For neoliberals, both those things are revolutionary. Credit where it’s due.

In fact, as far I could see there was nothing about lowering taxes at all, even though our company tax rate is towards the upper end of those in OECD countries. I guess the Initiative hasn’t done a report about the tax system – perhaps it will be a topic if there is a change of government, given that the Opposition parties propose a tax working group. Perhaps too there are no votes in arguing for lower company tax rates – in an overheated climate of angst about multinationals and tax – but, as the Initiative note, the role of a think tank shouldn’t be to be popular.

And now to revert to my earlier comments about the tone of the scene-setting introductory chapter. It is relentlessly upbeat. Apparently

New Zealand is not just doing well but doing spectacularly well on many measures.

And

Instead of taking this performance for granted, we need to celebrate it.

Ending on tones that could have been taken from Land of Hope and Glory

Land of Hope and Glory, Mother of the Free,

How shall we extol thee, who are born of thee?

Wider still and wider shall thy bounds be set;

God, who made thee mighty, make thee mightier yet,

God, who made thee mighty, make thee mightier yet.

Or, as the Initiative puts it

the Initiative takes great pride and satisfaction in helping make our great country greater still.

Of course there is a lot to like about New Zealand. Most countries in the world have far lower material living standards, however one wants to assess them.

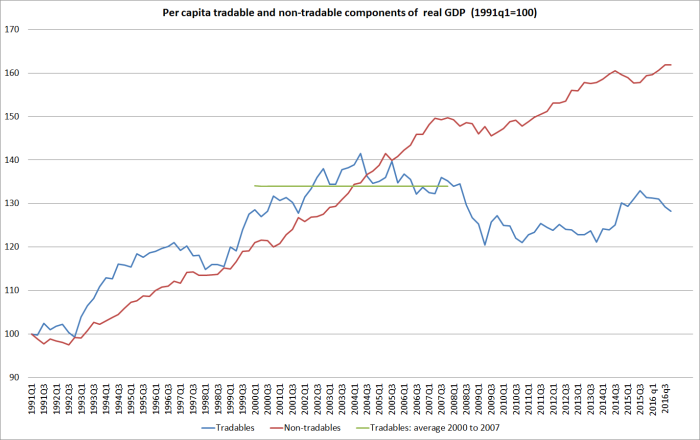

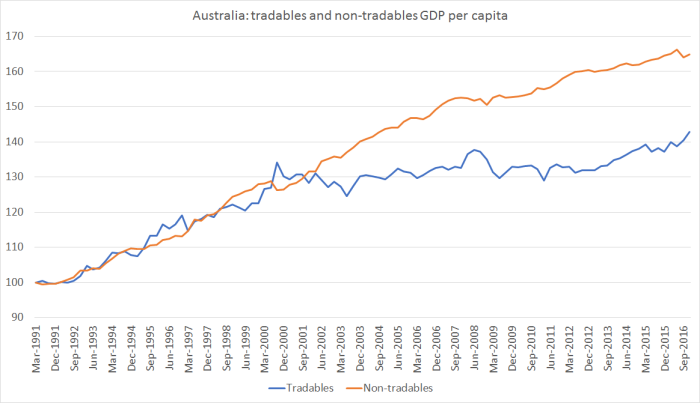

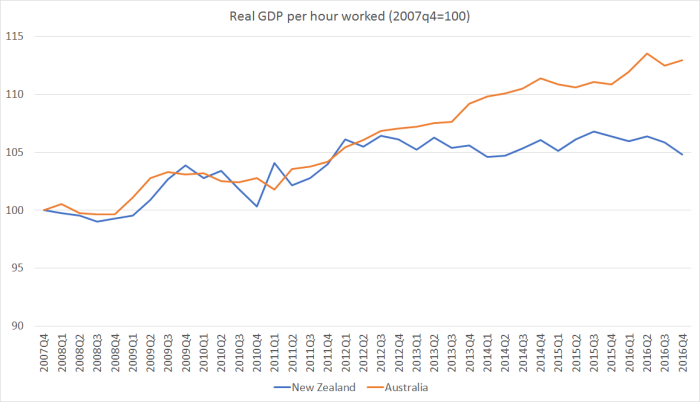

But what the Initiative seems to want its readers to forget – and perhaps it is just because many of their staff are so new to New Zealand that that history hasn’t yet made much impression – is that not long ago, New Zealand wasn’t just better than most countries, it was a better place to live than almost all of them. Norway was somewhere well down the scale, as were France and Germany, let alone Singapore and Japan. One can’t put too much weight on single estimates for single years, but 100 years ago we vied only with the US, Australia and perhaps the UK and Switzerland for top ranking. My grandparents were just starting out in the workforce then. Even in early 1950s – when my parents were starting out – we were still in the top handful, helped a bit by escaping the direct ravages of war. And now? Now, whether you look at GDP per capita or GDP per hour worked, or dig down and look at NNI (net national income) measures, we don’t score well. Of the OECD countries, we are perhaps 23rd, and showing no signs of improving. In the league tables, and depending on your precise measure, we vie with places like Slovenia and Slovakia (still regions of communist countries when we were doing our liberalising reforms in the 1980s) and Greece, Israel, Korea and Spain. In our European history, New Zealand has never before been as poor and relatively unproductive as these countries. And as the Initiative rightly stresses, economic growth – and surely even they mean it in per capita terms – matters. We haven’t delivered it, and there is no point pretending otherwise.

Is GDP everything? No, of course not. But if you want a balanced assessment of New Zealand – and such hardheaded asssessments are the only sensible starting point for good diagnosis and prescription – one could also point to things like:

- a homicide rate that is around the middle of OECD countries,

- an incarceration rate (a “fiscal and moral failure” as the Prime Minister put it) far higher than most,

- shocking domestic violence rates,

- wide disparities between Maori and Maori economic and life outcomes,

- as well as more mundane, but ubiquitous, scandals like the housing market.

Oliver Hartwich is glad to have come to New Zealand. He’s found a good niche here and I wish him all the best. Life is comfortable for upper income people in central Wellington. But what have New Zealanders been doing?

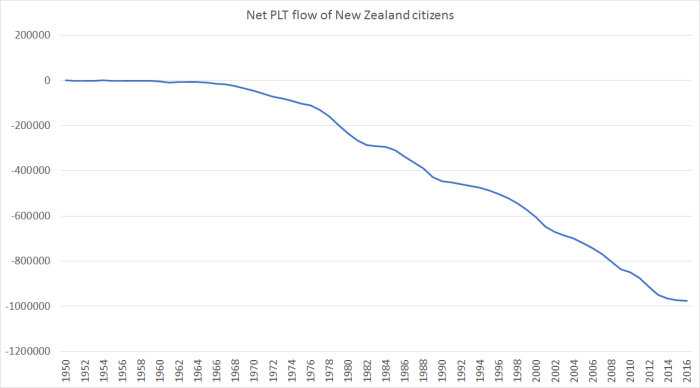

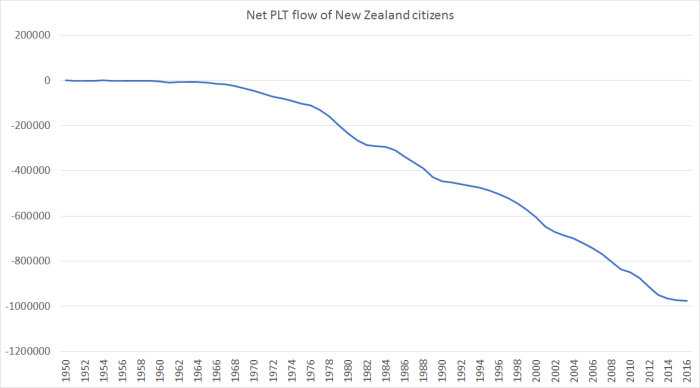

Here is the chart, since 1950, of the cumulative net immigration flow of New Zealand citizens.

In the 50 years to 2016 that was a net outflow of 963000 New Zealanders. The average population over that 50 years was about 3.7 million. Roughly a quarter of all New Zealanders have left (net) and not come back. It is a staggering symptom of failure and underperformance here, that so many people – in a relatively rich country – saw what they regarded as better opportunities abroad and went after them. Well-performing countries just don’t experience that sort of exodus. Most of us don’t want a repeat, or a resumption of larger scale outflows once the Australian labour market picks up. But to read the New Zealand Initiative’s report, one wouldn’t even know it was an issue.

Nearing the end of his rhapsodic introduction Hartwich observes

For policy experts such as my colleagues at the Initiative, New Zealand does not provide the same challenges one faces in solving the Greek debt crisis, organising Brexit, or fighting home-grown extremism.

It should. After all, that sort of outflow of our own people, that sort of sustained economic underperformance, is unknown in reasonably well-governed countries in modern times. If I can end on my own modestly upbeat note, we aren’t Argentina, Venezuela or Cuba……and yet we’ve experienced the staggering slippage that shows no sign of reversing itself. There are plenty of challenges for the next manifesto, if they interested in actually engaging with the specifics of New Zealand’s experience.

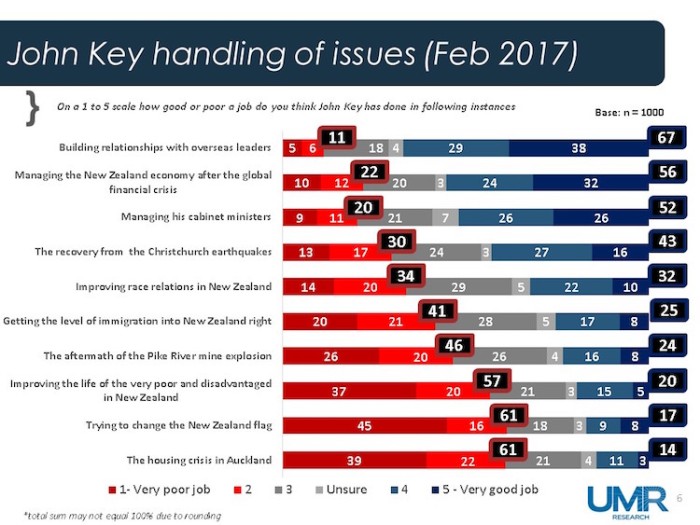

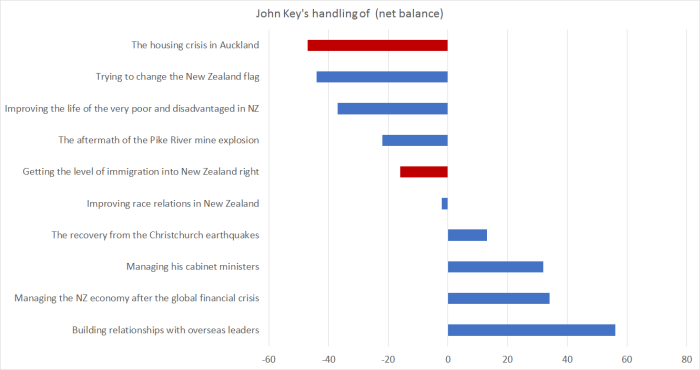

In some areas, Key rated very well, as one might expect (he did after all lead his party to three election victories). Relationships with foreign leaders scored as highly as you might expect from someone who seemed generally to be regarded as “the sort of person you want to have a beer with”. And if the government didn’t do anything much in the wake of the “global financial crisis”, arguably it didn’t have to – after all it was mostly a North Atlantic crisis, and when the crisis ended there, so did the worst of the backwash in the rest of the world. But if you are in office, you tend to get the credit.

In some areas, Key rated very well, as one might expect (he did after all lead his party to three election victories). Relationships with foreign leaders scored as highly as you might expect from someone who seemed generally to be regarded as “the sort of person you want to have a beer with”. And if the government didn’t do anything much in the wake of the “global financial crisis”, arguably it didn’t have to – after all it was mostly a North Atlantic crisis, and when the crisis ended there, so did the worst of the backwash in the rest of the world. But if you are in office, you tend to get the credit.