The parliamentary Labour Party has been showing signs of being serious about proposing steps that would, as they see it, unwind the structural impediments that keep urban land prices high and slow down the construction of new housing. Their housing spokesman (and campaign chairman) Phil Twyford has indicated that Labour wants to get rid of the artificial urban limits around cities, especially Auckland, and even managed a joint op-ed with the New Zealand Initiative on that.

Welcome – and no doubt genuine – as it all is, I’m still somewhat sceptical about what it will mean in practice. Any Labour government is near-certain to require the support of the Greens, not known for their support for such flexibility. And Labour or Labour-associated mayors lead our three largest cities, but there has been little sign of those Councils or mayors leading the way in freeing up urban land supply. There is a great deal councils could do if they wanted to. And even if they ran into legal challenges under current legislation, they could still be laying down markers as to the likely direction of reform when Labour returns to national office.

Last week Phil Twyford was out with another interesting idea in the same broad area – very long-term infrastructure bonds paid back by targeted rates – which again garnered public support from the New Zealand Initiative. Twyford sketched out his idea in an op-ed in the Herald, and also gave a substantive interview on it to interest.co.nz, who covered it in an article here. A reader with ties to the Labour Party suggested that I might like to write about it. My interest in the details of local authority finance is, sadly, quite limited, but I’ve been mulling over what to make of the proposal for the last few days. Is it really a proposal that, if adopted, might make a useful difference?

One difficulty in reaching a strong view is that the idea is no more than sketched out at the moment, and many of the details could matter quite a lot.

Some have argued that New Zealand should introduce, or allow, the sort of model used in many parts of Texas – Municipal Utility Districts – where developers of new residential areas outside existing city limits can form an incorporation, with its own governance structure, which in turn borrows to finance infrastructure developments and the provision of utilities such as water, sewerage and even parks. The bonds are then serviced by user charges and property taxes on the properties within the specific district. The New Zealand Initiative has written favourably about them (reported here), and I found an interesting recent Texan newspaper article that captured some of the colour/flavour of these sorts of vehicles. Whatever the merits of these schemes – and there seem to be some downsides too – they aren’t what Twyford and the Labour Party are proposing.

There are some real issues they are trying to address. As Twyford notes

The council is up against its debt ceiling and last week put the brakes on large-scale housing projects in Kumeu, Huapai and Riverhead until more progress is made on roads, stormwater and the like.

When the population of a city is growing as rapidly as Auckland’s, the existing debt ceilings are almost certainly flawed. There is a huge difference in the amount of debt, relative to (say) current revenue, that should prudently be taken on in a local authority region with no population growth than in a region that is seeing 2 or 3 per cent population growth per annum. We saw this at a national level when New Zealand and Australia were rapidly developing prior to World War One. Overall government spending as a share of GDP was much lower than it is today, but debt levels (again as a share of GDP) were much higher – in excess of 100 per cent. It wasn’t a problem, and markets didn’t see it as a problem.

Some of the current problem then seems to arise from a reluctance to use targeted rates, to ensure that purchasers of the new properties bear the cost of the infrastructure involved in developing those properties. Development contribution levies presumably go only part of the way. If owners – present or future – of the newly-developed sections bore the full cost of the infrastructure it isn’t clear what (economic) reason the Council could have for standing in the way of future residential developments. Planners’, bureaucrats’, and politicians’ visions as to what the city “should” look like are quite another problem – and not one that Twyford’s proposal seems to address at all.

Twyford describes the problem this way

Developers under current rules have to finance infrastructure within a subdivision and are levied by the council for a share of the cost of connecting to the wider roading and water systems as well as parks.

Many developers struggle with the sums of money involved and it adds cost and delay to projects.

But it isn’t clear that the issue here is really infrastructure finance. Developers need to finance all the costs of bringing properties to market, including covering both the delays that are perhaps inevitable in complex projects, and those brought on by the regulatory approvals processes. The largest chunk of those costs typically wouldn’t be the infrastructure (I’d have thought) but the unimproved value of the land (recall that urban and peripheral urban land prices are really what are sky-high). And property development is risky – even though the Reserve Bank’s LVR restrictions weirdly exclude new construction, new developments are where far and away the greatest risks lie. Lend on an existing house in Mt Eden and the risks are far lower than lending on a new development in Huapai. Sections might sit unsold, or undeveloped for years. New houses might do so too – there was plenty of that in Dublin after the boom ended.

There has been talk recently of banks becoming more cautious about lending for new construction – perhaps partly from their own reassessments of risks, and partly at the prompting of parents, in response to APRA’s nudges. Broadly speaking, that seems to me quite welcome. Banks make their own credit judgements and sometimes they will be less willing to lend than the authorities might like. It is, of course, the money of their shareholders they are putting at risk.

But Labour talks of central government becoming a fairly large scale provider of finance.

Labour’s plan is for infrastructure within a development, as well as the connections to the wider networks, to be financed by 50-year bonds.

Instead of the developer picking up these costs and loading them on to the price tag of a new home, the bonds could be issued by a government agency – perhaps a specialist infrastructure unit within the Treasury.

Bonds issued in this way would be the cheapest finance available, taking advantage of the Government’s ability to borrow more cheaply than anyone else.

The plan seems to be for the government to issue long-term bonds, with the government standing behind the bonds, and then to on-lend the proceeds to developers, tied to specific projects. The bonds, in turn, would be serviced by targeted rates levied by local councils on properties within that development.

It all sounds fine when everything goes well (most things do), but here are a few of my problems/concerns:

- should we be comfortable with Treasury officials making loans to individual developers, with all the risks of political cronyism in the allocation of credit over time? At very least, lending would need to be done at much more of an arms-length from elected politicians (as, say, when the government provided loans through the Housing Corporation or the Rural Bank),

- on what basis would we think that Treasury officials – or even those of a more independent agency – are better placed to evaluate and monitor residential property development projects than banks and other private providers of development finance? Who has the stronger incentive to get it right?

- isn’t there a high risk that the weakest projects will tend to gravitate towards the government provider of finance (strong projects, strong developers, will typically be able to get on-market finance?). Isn’t that incentive greatest towards the peak of housing booms, when more conservative private lenders might start to pull back from the funding market?

- how is cost-control ensured? If developers can simply shift any cost blow-outs into mandatory targeted rates over the next 50 years, doesn’t that materially weaken incentives to bring projects in on time on budget?

- what is the proposed legal structure? Only Councils can levy and collect rates, targeted or otherwise. Are they, or the developer, legally liable for the borrowing from the government? Developers can and do go out of business quite quickly. Councils don’t – but then don’t the debt ceiling concerns cut in again? And can councils credibly (or legally) commit to maintaining a whole series of specific targeted rate for the next 50 years? (And what are the protections for the property owners against arbitrary changes in these localised targeted rates?)

- and what happens if the project fails? If, for example, population growth slows up and a half-completed development lies idle for the next couple of decades. Will the owners of the land have to pay the targeted rate anyway and, if so, how resilient is this likely to prove politically?

It seems to me that the proposal is meant to have two main attractions:

- part of the development cost – infrastructure costs – are financed at a lower (government) interest rate, and

- the headline cost of a new house would probably be reduced.

But in substantive terms, neither is really that much of a gain. The cheaper government financing cost is only available – in Twyford’s own words – because the government’s credit risk is protected by the use of targeted rates. But money that the government has first claim on isn’t available to service other obligations. The infrastructure bonds might well be rock solid, but the rest of any borrowing people had taken out to finance a new property would be just that much riskier. Incomes don’t rise, and servicing the infrastructure bonds would have first call on what income there was. Banks would presumably take that into account (including in deciding how much, and at what margin, they will be willing to lend).

And if the headline cost of a new house is reduced, so what? If I have a choice between paying $700000 for a new house, or paying $600000 for the house and then having to service $100000 of infrastructure bonds issued by the government to cover the development costs of the house, it doesn’t make much difference to me. If the infrastructure bonds really were 50 year ones, the annual servicing burden might be a little lower than otherwise. Then again, New Zealand already has the highest real interest rates in the advanced world, so the notion of paying those high rates for that long might not be overly attractive.

And thus I suspect Twyford is wrong about a possible third benefit. He argues

Reduce the infrastructure component of the price of a new home, and you’ll reduce not only new house prices but eventually prices across the whole market.

That’s unlikely. If I’m looking at a $700000 house (with no targeted rates), and comparing it to that new house in the previous paragraph, changing the financing pattern for the new house isn’t likely to change much about what I’d be willing to pay for the existing house. Of course, if the policy really did increase the flow of new supply of houses and developed land, there would be benefit in lowering the prices of existing properties. But simply lowering the headline cost of a new house (while loading an equivalent amount into infrastructure bonds) won’t change that.

In many respects, I’m sorry to reach a negative conclusion. It is great that the Labour Party is looking for ways to make a difference to the housing market, not just for a few months but permanently (and it is a disgrace that we’ve had 15 years of increasingly unaffordable house prices under both Labour and National-led governments). And, of course, this isn’t the only (or probably even the main) component of their housing plan

Fixing the housing crisis and managing Auckland’s growth needs sustained reform on many fronts. Labour will build 100,000 affordable homes, tax speculators, and set minimum standards to make rentals warm and dry. We will free up the planning rules by relaxing height and density rules around town centres and on transport routes, as well as replacing the urban growth boundary with more intensive spatial planning.

But I’m sceptical that the infrastructure bond proposal is a suitable response to a serious constraint or that, even if the governance and monitoring concerns could be overcome, that it would make much difference to house and urban land prices.

If they wanted to consider a bold initiative, how about promising that any private land within 100 kms of Queen St could be built on to, say, two storeys without further resource consents? With a similar policy – perhaps 50 kms circles – for Hamilton and Tauranga, it would seem much more likely to make a real difference in lowering land prices – the biggest financing issues not just for developers, but for ultimate purchasers. There are other pieces of the jigsaw, but changing the rules that underpin expectations of future potential land values is probably the biggest component of the problem.

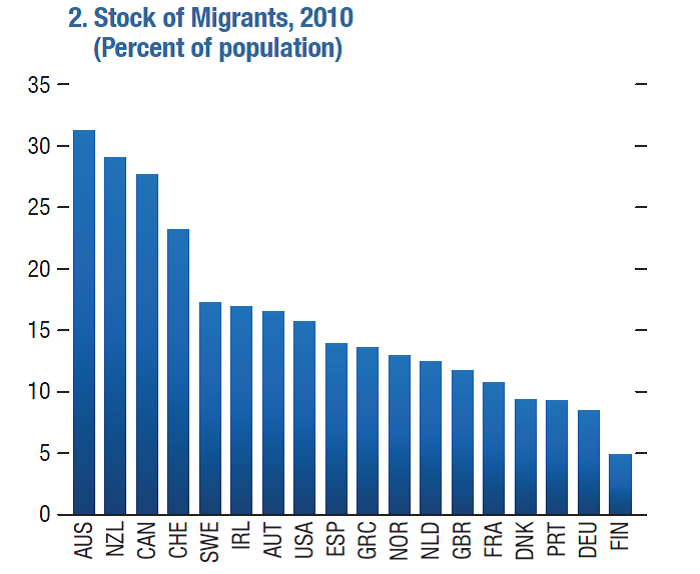

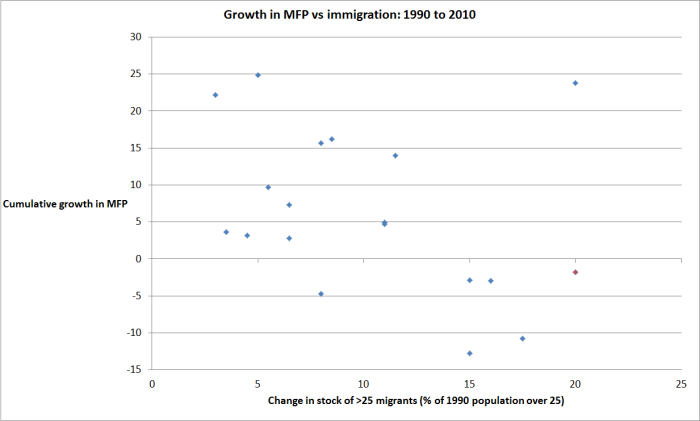

Throw in a sharp cut in the immigration residence approvals target – not mostly to solve the housing problem, but because there is no evidence New Zealanders are gaining from the large scale non-citizen immigration – and properties in or near Auckland would be much more affordable really rather quickly.