Browsing a few weeks ago in a secondhand bookshop in an obscure Northland village, I stumbled on Tricontinental: The Rise and Fall of a Merchant Bank, a fascinating 1995 book documenting the utter disaster that Australia’s largest “merchant bank” – by then wholly-owned by the State Bank of Victoria – became in the late 1980s. That failure was followed by a Royal Commission, helping to ensure that events around it – including the failures of management, auditors, owners, politicians and regulators – are better-documented (or more accessibly documented) than in most bank failures.

In both New Zealand and Australia, the mid-1980s was a period of great exuberance in banks and financial markets. Controls that had been in place for decades were removed in pretty short-order (the changes were more far-reaching in New Zealand than in Australia, but Australia’s changes were large enough). Exchange controls were removed, exchange rates were floated, interest rate controls were removed, new entrants to the financial system were allowed, and in both countries there were reforming (notionally) left-wing governments. Brighter futures for all were in prospect.

Stock markets soared and those who were energetic and lucky quickly made themselves huge fortunes – most of which had gone again only a few years later. Debt paved the way, financing takeovers, often-questionable real investment projects (the Australasian commercial property glut followed) and (in Australia in particular) massive reshuffles of media holdings as the regulatory ground shifted. Total credit – and especially total business credit – saw almost explosive growth. Names like Bond, Holmes a Court, Brierley, Judge, Hawkins, Skase and so on dominated the business media. There was even ridiculous talk of New Zealand firms having a comparative advantage in takeovers. The media were often enthralled by what was going on – it made for great stories – and it was probably hard for politicians to resist either. After all, a lot of political capital had been staked on those reforms, and associating with success tends to be much more attractive to politicians than the alternative. On this side of the Tasman, the defining images of the period are probably (a) newly-listed goat farms, and (b) the way shares in the Fay/Richwhite entity rose and fell with the successes (and subsequent failure) of the New Zealand entry in the 1986/87 America’s Cup in Perth.

Much of what went on in those years ended very badly. Many of the key business figures afterwards spent time in prison. Many major corporates failed – not in itself a bad thing – and many banks did too. On this side of the Tasman, the well-publicized disasters were the (predominantly government-owned) DFC and BNZ, and the less visible NZI Bank. In Australia, Westpac came under extreme stress, and the State Banks of Victoria and South Australia were the most visible calamities. The State Bank of Victoria enabled Tricontinental – and in turn Tricontinental did the lending that was enough to end its parent’s 150 year independent existence.

Tricontinental didn’t start (in 1969) as a government-owned entity. Indeed, the name reflected the early spread shareholding – stakes held by banks on three continents, dating from the pre-deregulation days when the best way for foreign banks to get into the Australian market had been through the merchant banking sector, which in turn was beyond the scope of many of the regulatory restrictions (eg on how short a term deposit could be) on banks. It wasn’t wildly different here – there had been huge disintermediation to the non-bank sector in the couple of decades prior to our deregulation.

But in the post-1984 ownership reshuffles, Tricontinental – always a fairly aggressive, but fairly small, player – became a wholly-owned subsidiary of the (Victorian government owned) State Bank of Victoria. And in the same period, there was the rapid rise of Ian Johns, first as Tricontinental’s lending manager and then as CEO. Johns was pretty young, had never (that I could see from the book) been through a serious economic downturn, but had the drive and aggression that enabled him to forge relationships and build a rapidly-growing lending business – typically with emerging “entrepreneurs”, and generally not with the “big end of town”. And if funding such a fast-growing lending book might have been a bit of an issue – even in those heady days – even that concern largely dissipated once Tricontinental came wholly under the wing of SBV – one of the establishment institutions of Victoria, historically the financial centre of Australia. SBV didn’t really even want to own Tricontinental in the long-term – they thought they were dressing it up for a sale. But in the meantime, there were next to no market disciplines, little or no regulatory discipline, and near non-existent self-discipline (including from the Board, the SBV Board, or SBV’s owners the Victorian government).

Reading the book, it was both staggering and sadly familiar just how badly wrong things went. Since 2008 I’ve read numerous books on the failures of individual institutions – in Iceland, Ireland, the UK, the US, the Netherlands, past and present, as well as more general treatments of banking crises in these countries and Japan, Finland, Sweden, Norway. There aren’t many new things under the sun, and Tricontinental wasn’t one of them. In a way, it was a product of its time, but that doesn’t take away the responsibility of individuals and institutions.

Credit growth doesn’t just happen. It needs people who want to borrow and people who are willing to lend. In post-liberalization Australia (and New Zealand) there was no shortage of people with superficially plausible schemes who were willing borrow whatever anyone would lend. Sadly, there were all too many people willing to lend – attracted by some mix of the high fees, high credit spreads (Tricontinental apparently charged both), the mood the times, expectations of shareholders’ (everyone else is booking high profits, why not you?) – and few people willing to say no. Of course, those who had tried to say no might well have been shoved aside – “get with the new world” – but as far as one can tell from the book, hardly anyone ever tried to say no in Tricontinential/SBV. The CEO drove the lending business, there was little robust internal credit analysis, the emphasis was on fast turnaround of proposals, and while Board approval was required for all major loans, often this was sought by couriering out papers to individual Board members’ and requiring consent within 24 hours (and Board members weren’t just the glittering “great and good”; many look like the sort of people who would easily pass “fit and proper” tests). Loans were collateralised, but the quality of security was typically poor (and often much worse than the not-overly-curious Board realized). Internal guidelines – eg on concentrated exposures – were routinely ignored, and redefined to suit, and recordkeeping and reporting systems were grossly inadequate. Auditors rarely asked hard questions – and had they done so would no doubt have jeopardized their mandate – and no one anywhere seems to have wanted to explore the possibility that things could go very badly wrong. The Reserve Bank of Australia had few formal regulatory powers – state banks were established under specific state legislation, and merchant banks weren’t generally supervised – but hardly pushed to the limits its informal powers of persuasion or access.

After the 1987 sharemarket crash it all came a cropper. Not on day one – it took several years for the full scale of the disaster to become apparent (not that different from the situation here, where DFC only finally failed two years after the crash) – but the fate was largely sealed then. Share prices didn’t keep rising indefinitely. Castles built in the air had their (lack of) foundations exposed. And the value of collateral quickly dissipated. Billions of dollars in loan losses were eventually recorded, destroying the parent, and (apparently) contributing in no small measure to the fall on the then Victorian Labor government.

As I noted, there was a Royal Commission inquiry into the failure – itself embroiled in political controversy and legal challenges. The authors of the book suggest that the Royal Commission bent over backwards to excuse many people, but no one seems to emerge that well from the episode. It wasn’t, as the Commission reports, mostly about criminality or corruption (although Johns did go on to serve time in prison on not-closely-related offences), but was caused mostly:

..by ordinary human failings, such as the careless taking of risks while chasing high rewards (in a decade noted for its commercial greed), complacent belief in the reliability of others, lack of attention to detail, and arrogant self-confidence in decision-making – all of which resulted in poor management and unsound business judgements.

They criticized Johns “arrogant self-confidence, lack of business acumen, naivety when dealing with well-known entrepreneurs, lack of candour at times amounting to deviousness, and unwillingness to admit error”, the CEO of SBV (who sat on the Tricontinental Board) (“he appears to have been weak when he should have been strong”), the Board chair, the Reserve Bank, and the rest of the SBV and Tricontinental directors.

Listed entities, with market disciplines, fail from time to time. In wild booms all too many get caught up to some extent in the excesses. And not all bank failures should be considered bad things. But it is difficult to escape the conclusion that government-owned banks are that much more prone to running into serious financial strife than others, perhaps particularly when they are run at arms-length in a more deregulated environment (it was hard for any bank to fail in 1960s New Zealand or Australia). We saw it in New Zealand and Australia in the 1980s, and with the German landesbanks. Perceptions of too-big-to-fail around state-sponsored entities like the US agencies go in the same direction. And it is why I have never been comfortable with Kiwibank – and am only more uncomfortable if the planned reshuffling of ownership within the New Zealand state sector goes ahead. Market discipline doesn’t work perfectly – perfect isn’t a meaningful standard in human affairs – but it seems considerably better than the alternative, lack of market discipline. And, regulators being human, when market discipline is weak, regulators often aren’t much help anyway – they breath the same air, and are exposed to same hopes and dreams as the rest of us.

For anyone interested in Australasian financial history, the Tricontinental book is fascinating. I went looking to see what happened afterwards to some of the key characters – Johns after all was still quite young in the early 1990s – but Google failed me. There just doesn’t seem to be much around. But the interest is probably mostly in reliving the atmosphere of the times, when so much damage was wrought so quickly on both sides of the Tasman.

It is also, though, a reminder, of how poorly served New Zealand is in financial history. There is no comparable book about the DFC failure (although Christie Smith at the RBNZ did an interesting recent draft paper on it), nothing comparable on the BNZ failure, and there are no serious works of economic or financial history on the extraordinarily costly and disruptive banking and corporate period after 1984. There are small individual contributions (and I learned a lot from some memoirs by Len Bayliss on his experiences as a BNZ director during the period), but no single work of reference to send people to. There must be huge paper archives still around – both those of the institutions concerned and those of the Treasury and the Reserve Bank – and many of the players are still alive. A book of the Tricontinental sort written 2o years ago could have been no more than a first draft of history. At this distance, it is surely the opportunity for some more serious reflective historical analysis that would, among other things, secure the record for future reference.

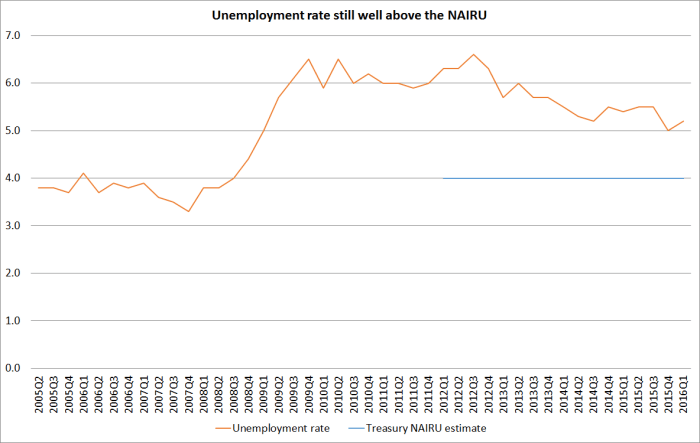

Reflecting on these sorts of institutional failures, it got me wondering again about the sorts of climates in which the risks build up that culminate in bank failures. Alan Greenspan’s phrase “irrational exuberance” springs to mind. There was plenty of exuberance in post-1984 New Zealand and Australia, with asset prices and credit rising extremely rapidly to match. Whole new paradigms for assessing, or ignoring, risk were championed. And in the respective domestic economies, times felt good too – in one headline indicator, New Zealand’s unemployment rate, in the midst of widespread economic restructuring, was around 4 per cent. Those look like the sorts of climates that characterized most of the advanced country crises of recent decades – Ireland recently, or Japan or the Nordics in the 1990s being the clearest examples. By contrast, today’s New Zealand – limping along with modest real per capita GDP growth, subdued confidence, lingering unemployment, few new or significant credit providers just doesn’t seem to fit the bill (no matter much the combination of population pressures and land use restrictions) drive house prices up. (I wrote a piece last year on the lack of parallels between now and 1987.)

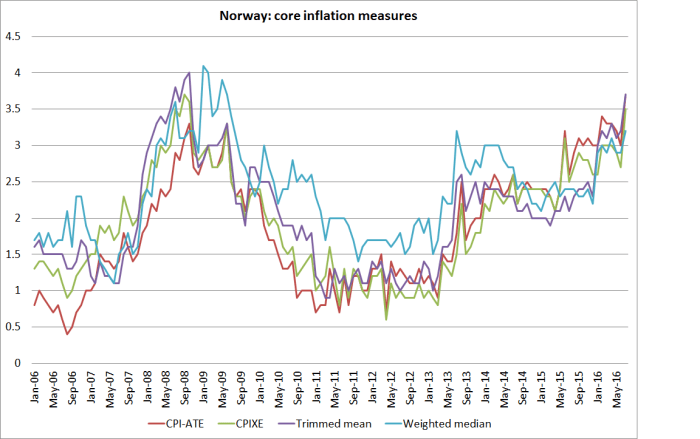

And here are two-year ahead inflation expectations in the two countries – the Reserve Bank survey for New Zealand, and a survey measure for Norway that I’ve taken from their MPS.

And here are two-year ahead inflation expectations in the two countries – the Reserve Bank survey for New Zealand, and a survey measure for Norway that I’ve taken from their MPS.