I’ve been laid aside (medically) this week so won’t be writing much about today’s MPS. But I had a few observations nonetheless

The OCR cut itself was really the least the Governor could do, especially having laid the groundwork with his interim statement a few weeks ago. It was interesting that for the first time since the easing cycle (better described as “reversal of the ill-judged tightening cycle”) got underway, the Bank now says not just that further easing “may” or “seems likely” to be required, but “will be required”. Of course, that is still conditional on their forecasts panning out, but it is pretty strong language for a central bank. It does rather prompt the question of why, if they are that confident they didn’t just cut the OCR by 50 basis points now. On their current forecasts, inflation wouldn’t have overshot the target – perhaps they’d have got back to the target midpoint at the start of 2018, rather than the September 2018 (still two years away, and well beyond the expiry of the Governor’s term) they currently project. Perhaps they’d even have got the exchange rate down somewhat – instead of another OCR review in which the exchange rate rises, at least on the day. And yet the Governor said they hadn’t had any serious discussion of the option of a 50 basis point cut. If so, that seems somewhat remiss – if nothing else, seriously thinking about alternative policy approaches can help clarify arguments, even if that alternative is never adopted.

As I watched the press conference, I thought the Governor was looking rather tired and beaten-down. In one sense that shouldn’t be too surprising. The whole story upon which he based monetary policy for the first half of his term simply turned to dust. There was no upsurge in inflation to get on top of, and instead he has been managing a staged withdrawal for more than a year now, still reluctant ever to acknowledge a mistake.

Perhaps more importantly, there is a reluctance to take responsibility: New Zealand’s inflation rate is largely something that New Zealand’s central bank controls. There are all sorts of influences on prices, but we – citizens – pay the Bank to recognize those influences and respond sufficiently vigorously to keep inflation near the target we’ve set for them. Low world inflation is, for us, just one of those things. We don’t control it, but we can adjust domestic monetary policy to take advantage of it. And I say “take advantage” deliberately: low world inflation would have given us the opportunity to have had lower real domestic interest rates over the last few years, and with it stronger domestic activity, lower unemployment, a lower exchange rate, and inflation closer to target. But even now, the Governor is clearly reluctant. He keeps emphasizing the “unprecedented” global stimulus – even though the best evidence of “stimulus” is something being stimulated, and there is little sign of global inflation being stimulated much – and, domestically, “accommodative” monetary policy. But again, where is there much sign of the “accommodation”? Inflation is consistently well below target, and the unemployment rate has been above any estimate of a NAIRU for 7 years now. No doubt some will respond “look at house prices”, to which my response is to refer people to the structural pressures: the interaction of rapid population growth and land use restrictions.

The Bank remains optimistic that GDP growth is going to accelerate, expecting 3.5 per cent per annum over the next couple of years. Perhaps they will be right, but I still don’t see what is likely to bring about such stronger growth. If anything, waning population pressures should lower headline growth, even if per capita growth were to strengthen a little. Between the high exchange rate, subdued commodity prices, subdued world activity, and a waning (and then reversing) impulse from net migration, I’d have thought New Zealand will struggle to grow as fast over the next year as it has done this year.

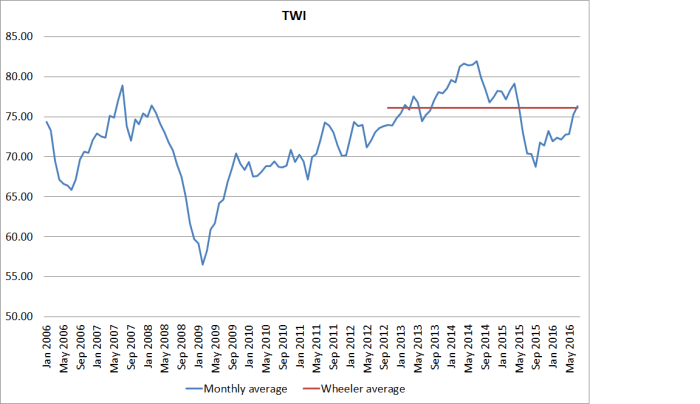

I’ve noted previously that the Governor would be well-advised to stop making open calls that the “exchange rate needs to come down”. This morning, the TWI was sitting just above the average level that has prevailed over his entire term. It was higher when markets thought we’d go on tightening for some time, and lower when it looked like the rest of the world might start tightening. But over four years it hasn’t really gone anywhere.

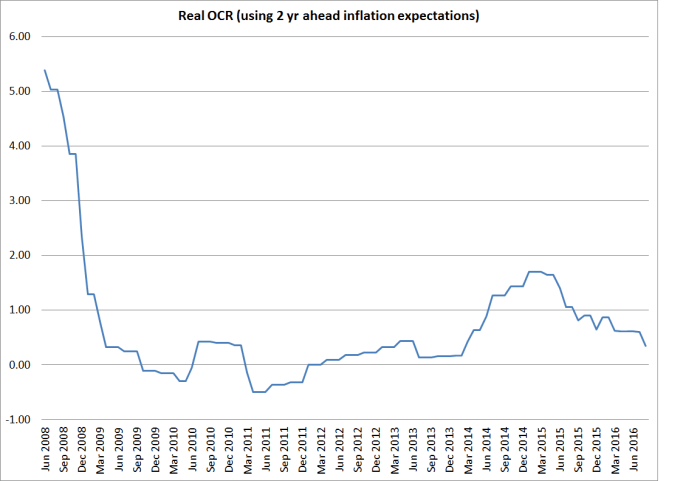

And in many ways that isn’t very surprising. After all, real interest rates in New Zealand haven’t gone far for years either.

Even after this morning’s cut, the real OCR on this measure is still only about where it was just before the February 2011 earthquakes hit. Back then, we were in middle of coping with the increase in the rate of GST and no one really recognized just how weak New Zealand or global inflation pressures were turning out to be. There is no easy rule of thumb to say where the OCR should be now, but I think there is a pretty strong case – in the context of the inflation targeting regime, which the Governor strongly (and rightly) recommitted to this morning – that it should be lower than it is now. Given how much we’ve been surprised over the last few years – about things at home and abroad – one could pretty easily make a case for a negative real OCR right now.

A few years ago, Mario Draghi the head of ECB galvanized and totally changed market sentiment about the euro-area with his off-the-cuff pledge to “do whatever it takes” to hold the euro together. We haven’t seen that sort of commitment in respect of New Zealand monetary policy. When asked this morning whether he’d be willing to take the OCR to zero if necessary, the Governor fended off the question. Instead, it would have been a great opportunity to say “yes, of course. We’ll look at the data every six weeks, but we are concerned about persistently low inflation – and about expectations drifting down, and about unemployment lingering high. We’ll do what it takes”. Instead, we heard unease that if the Bank did too much it might create “more damage” to the economy. Than what, I was prompted to wonder. As it is, New Zealand continues to look like the last bastion offering some – no longer much – yield to investors. Interest rates of 2 per cent aren’t much, but they are much higher than you can get in most places. If so, no wonder the exchange rate remains relatively high. And, relative to the Bank’s target, there is simply no need for interest rates to be that high – not even on the Bank’s own forecasts, let alone a more realistic assessment of capacity pressures.

The Bank attempts to make quite a lot in the MPS of the idea that capacity pressures are becoming real in New Zealand, while they are largely absent in the rest of the advanced world. They attempt to support that using various international output gap estimates, and their own estimates for New Zealand. As they, and we, know output gap estimates are very imprecise, and prone to considerable revisions over time (especially for estimates of where the economy is right now). For the last five years, the Bank has repeatedly tried to run the line that spare capacity has been used up in New Zealand, only to have to revise those estimates back again. Another way to look at these things is through the lens of unemployment rates, They aren’t a perfect measure, but are often more useful than output gap estimates, and relate back to some specific human concerns – people who are actually out looking for work. Here are the unemployment rates since 2005 for New Zealand, the OECD as a whole, and the G7 as a whole.

New Zealand’s unemployment rate has been consistently below the other lines – not surprising, as we have a more deregulated labour market than most. But all three lines went up a long way during the 2008/09 recession, and there is no sign that New Zealand’s has fallen faster since. If anything, it is rather the reverse. The gap between New Zealand’s unemployment rate and those of the rest of the advanced world is smaller than at any other time in this sample.

The answers to our inflation challenges – getting it up to and keeping it around target – really are in our own hands, or more specifically in the Governor’s hands. We could have had lower interest rates, a lower exchange rate, more demand, lower unemployment, and higher inflation. (And if the powers that be couldn’t fix up housing supply or immigration policy, the Governor could have required banks to hold larger capital buffers in case the domestic housing market caused future loan loss problems).