The Herald‘s Claire Trevett was perhaps being just a trifle unfair yesterday in commenting on the Reserve Bank’s “consultative” document on the latest iteration of the increasingly unpredictable LVR restrictions

The Reserve Bank’s definition of “consulting” appears to be akin to North Korean President Kim Jong Un’s

The Governor on the exchange rate tends to bring to mind parallels with the (misremembered) story of King Canute. Canute was trying to deliberately demonstrate to his courtiers how little command he actually had – none over the tide and the seas. But the Governor loftily – or perhaps plaintively – decrees that “a decline in the exchange rate is needed”, and the market really doesn’t pay that much attention. The exchange rate did fall a bit yesterday, and has pulled back some way over the last 10 days or so, but the exchange rate today is perhaps only a couple of per cent lower than the average over his whole term to date. For almost his entire term, he has been lamenting the strength of the exchange rate.

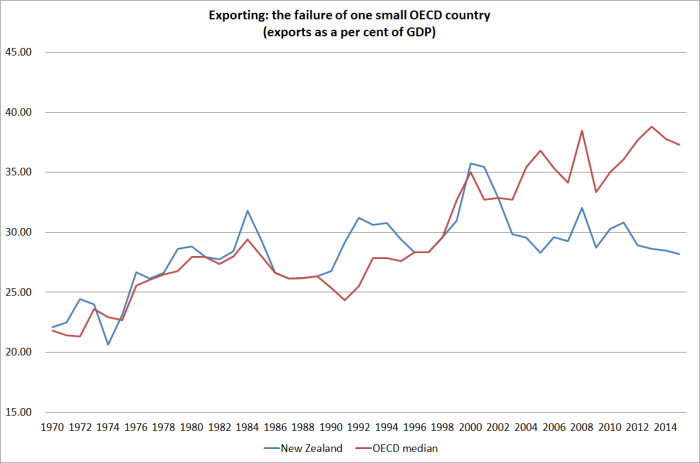

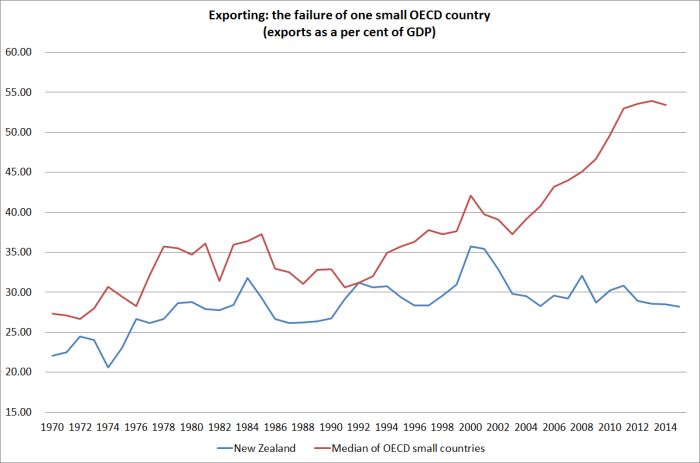

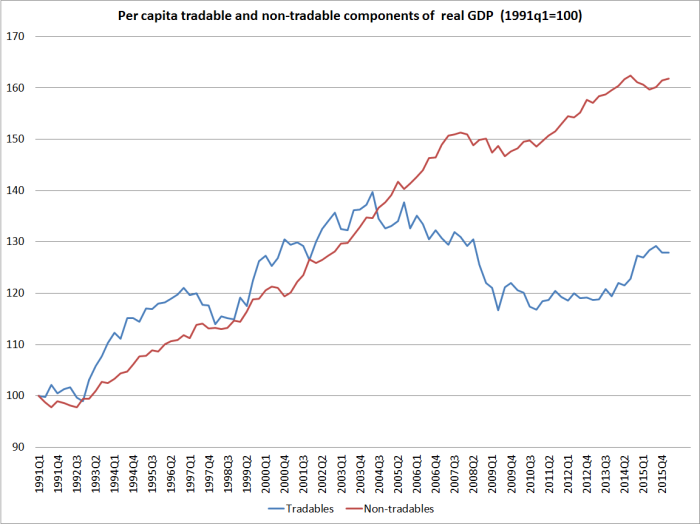

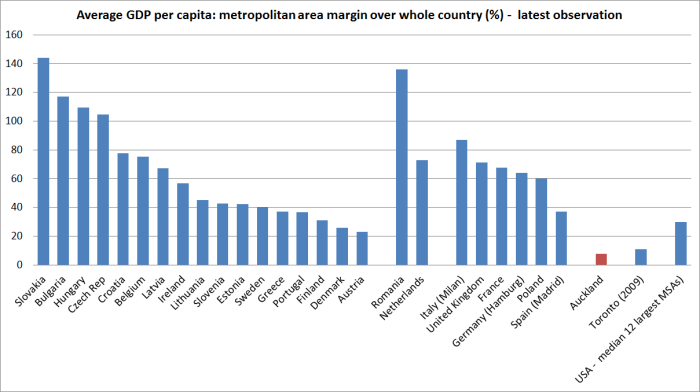

I’ve noted previously that I entirely agree with the Governor that a successful transformation of the New Zealand economy’s growth prospects is likely to require a sustained and substantial fall in New Zealand’s real exchange rate – a substantial fall in the prices of non-tradables relative to the prices of tradables. But nothing the Reserve Bank does, or could do, has anything much to do with bringing about that sort of change. It isn’t some fault or failing of financial markets either. Rather, responsibility for the persistent pressures on domestic resources that have given us a real exchange rate persistently out of line with our deteriorating relative productivity performance rests squarely in the Beehive. The choices successive governments make – and both major parties still defend – explain the bulk of our underperformance. Here is a chart I ran a few weeks ago. If anything, I suspect – but of course can’t prove formally – that we need the exchange rate to fluctuate below that 1984 to 2003 average for a decade or two, not the 20 per cent above that average we’ve had for the last decade and more.

But in the shorter-term (perhaps even periods of several years) monetary policy choices make a difference. Sometimes quite a large difference indeed. Notice the big fall in the exchange rate following the 1990s boom. The TWI briefly fell almost as low, in real terms, as it reached following the 1984 devaluation – and for the economic elite in 1984/85, one of the big challenges then was felt to be “cementing in” that lower level of the real exchange rate.

During this period around the turn of the century, the NZD/USD exchange rate was below .5000 for almost three years. At the trough in late 2000 it was around .3900. What else was going on?

In New Zealand, it was the first year of the new Labour-Alliance government, and the business community did not like the policies, or attitudes, of that government one little bit. I was head of the Reserve Bank’s Financial Markets Department at the time, and used to go along to Board meetings each month. One particularly prominent and vocal member constantly wanted to get me to say that the weak exchange rate was all a market judgement on the new government. I usually pushed back quite strongly.

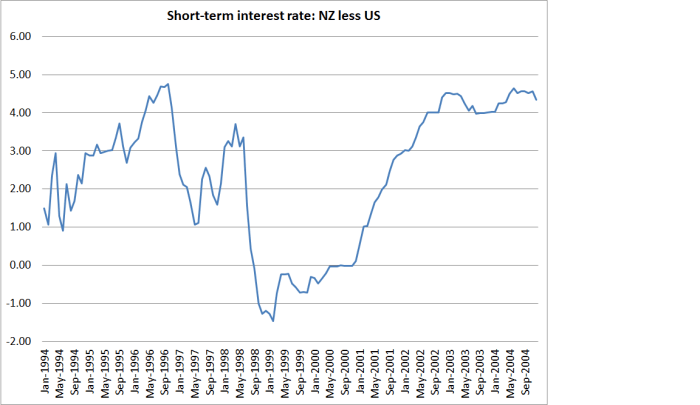

And here is why.

This chart uses OECD short-term interest rate data for 1994 to 2004. During that period from mid-late 1998 to the start of 2001, New Zealand short-term interest rates were at or below the level in the United States. It is the only time in the whole post-liberalization period when that has been so. The respective central banks judged that that was where their own interest rates needed to be to keep inflation at or near target (a formal target in the New Zealand case, and an informal target back then in the US).

It isn’t a mechanical relationship by any means. Apart from anything else, expected interest rates tend to matter at least as much as actual short-term rates – ie the expected future path of policy. And other expected returns mattered too. Even after the NASDAQ had peaked in early 2000, there was still an important theme around markets of “new economies” (with the tech boom) and old economies. The NZD and AUD – not seen as currecies of high tech “new economies” – were very weak in response.

The Governor can’t change the structural fundamentals that influence savings and investment preferences in New Zealand. But he has our OCR in his personal control. If he were to cut the OCR to 1.5 per cent, there would still be quite a large margin over US interest rates – unlike the situation in 1999 and 2000 – but that gap would be quite materially narrower than it is now. Perhaps the OCR might even be able to go below 1.5 per cent – after all, it is not as if the resulting margins to world interest rates would be unprecedented – but we’d have to see how the data unfolded.

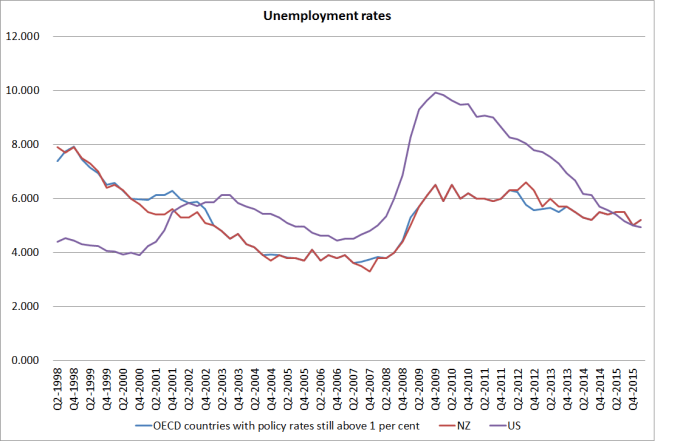

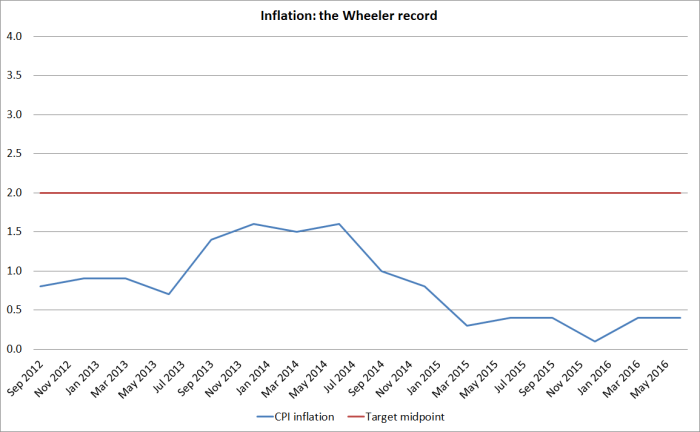

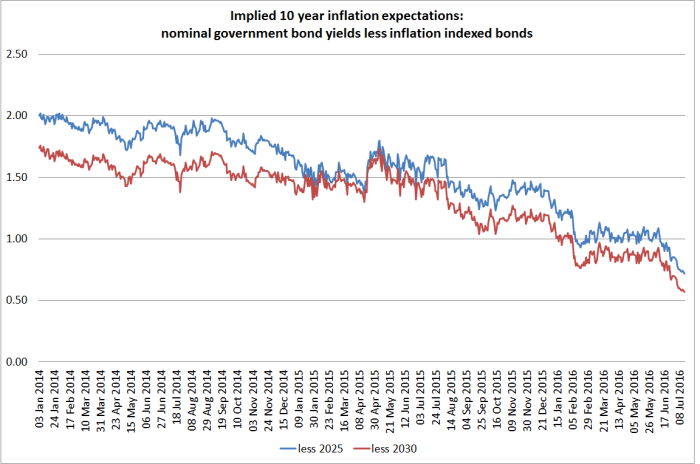

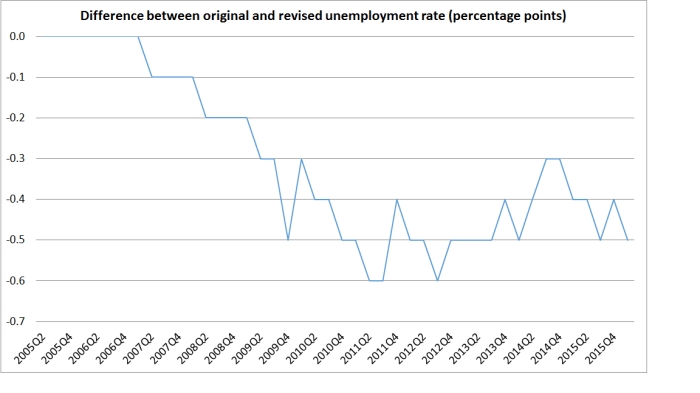

The Governor can’t just set the OCR on a whim. Instead he is required to deliver on an inflation target. But we know that New Zealand’s inflation rate has been persistently very low relative to the target the government set for the Bank. Among the OECD countries where the central bank still has some material monetary policy discretion – say, a policy interest rate still above 1 per cent – our inflation rate has also been falling away relative to the median in those other advanced economies (a sample which includes Australia). Inflation just isn’t a constraint at present – if anything, it is the absence of enough inflation that is the problem. And is the economy under mounting pressure? Well, by contrast with the United States where the unemployment rate is almost right back to where it was prior to the recession, in New Zealand – even on the latest SNZ revisions – (and in the median of those other higher interest rate OECD countries) the unemployment rate is almost 2 percentage points higher than it was prior to the recession.

There is simply no sign that the real economy could not cope with materially lower policy interest rates – if anything, the evidence is pretty clear that it could do with the boost (or rather with the inappropriately restraining hand of the Reserve Bank being eased up).

The gap between New Zealand and US long-term interest rates has “collapsed” in recent months – the gap between 10 year nominal bond rates is now only around 65 basis points. That suggests that markets actually think quite a bit of policy rate convergence is coming. But they can’t be sure when, as the Governor remains so reluctant to cut the OCR and has been prone to inconsistent communications. The economic case for a 50 basis point OCR cut next month, foreshadowing further cuts to come, is reasonably strong. I don’t expect the Governor to adopt that policy, but if he is serious about getting monetary policy out of the way of the exchange rate adjustment he seeks, it is exactly the policy he should adopt.

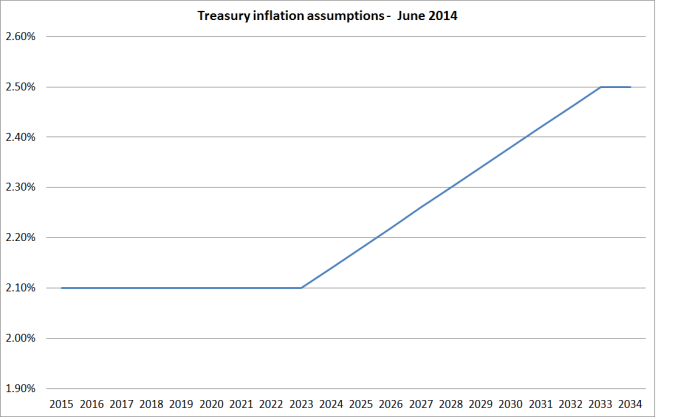

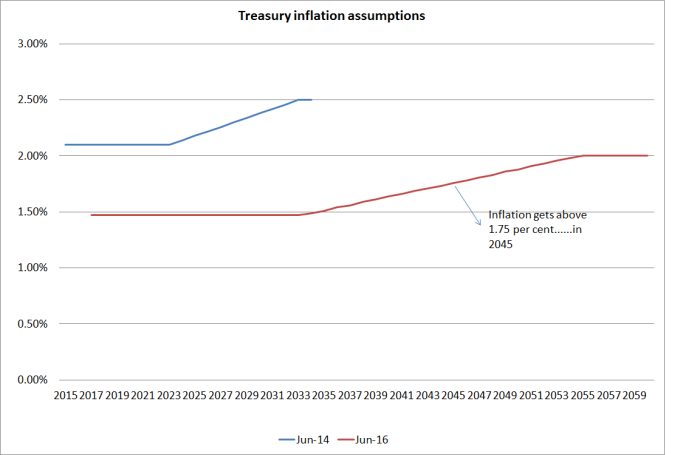

No doubt, some at the Reserve Bank will continue to cite their estimates of neutral interest rates being around 4 per cent – as the Assistant Governor apparently recently told FEC. If you asked me where I though global real interest rates would converge back to over the next 20 years, I too might talk in terms of a 2 per cent real interest rate (so with inflation targets centred on 2 per cent, perhaps something around 4 per cent). But that is simply not a meaningful basis for making monetary policy today. We don’t know where “neutral” interest rates are now, but most of the external evidence suggests monetary policy isn’t particularly accommodative at all – rather it has sluggishly adjusted towards whatever has changed in the real economy. In New Zealand’s case, that failure to adopt a practically accommodative policy is holding the exchange rate higher than it needs to be – higher than the Governor himself would like. To that extent, the solution is in his hands.

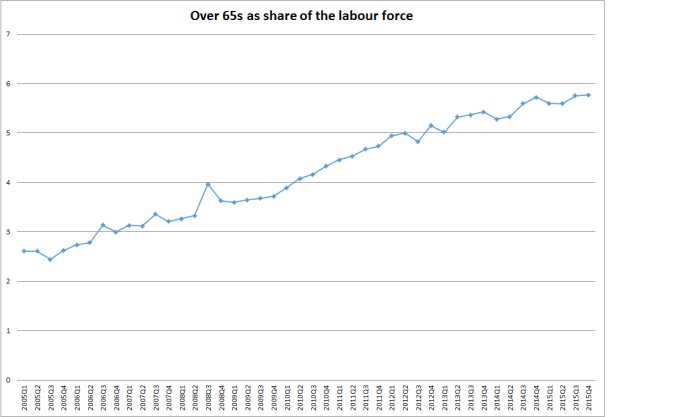

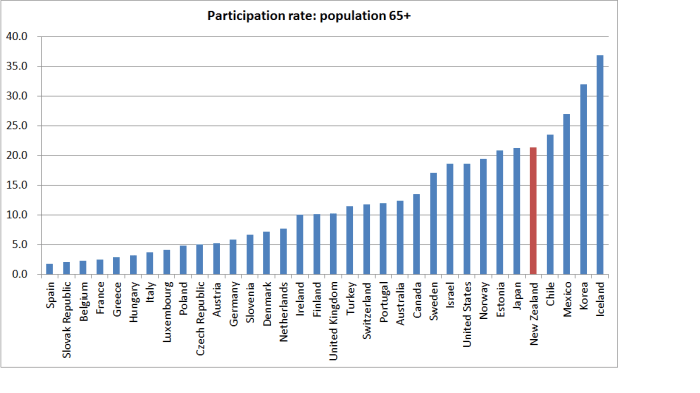

And the unemployment rate among older people is very low indeed – before the recession and now both around 1.5 per cent. That makes sense – older people have New Zealand Superannuation to fall back on, with no work test, so there is typically no urgency to find another job (to be “actively seeking”). But it is a very different – and less cyclical – unemployment rate than that for the rest of the workforce.

And the unemployment rate among older people is very low indeed – before the recession and now both around 1.5 per cent. That makes sense – older people have New Zealand Superannuation to fall back on, with no work test, so there is typically no urgency to find another job (to be “actively seeking”). But it is a very different – and less cyclical – unemployment rate than that for the rest of the workforce.