Yesterday I mentioned that it is often forgotten that we already have a near-universal indexed annuity that ensures that no elderly New Zealander need ever end up in extreme poverty.

New Zealand Superannuation is paid from age 65 to any citizen or permanent resident living in New Zealand who meets some (relatively undemanding) accumulated residency requirements, at a rate equal to (for a couple) 66 per cent of the average net wage.

Of course, nothing is risk-free in life. The New Zealand government is most unlikely to directly default on its debts in the next few decades. But there is “policy risk”: as the 2025 Taskforce put it a few years ago “New Zealand has a long history of revisiting its state pension arrangements”. But for resident New Zealanders at the bottom of the income distribution it makes perfect sense to rely almost solely on NZS for income support in old age. Whatever changes have been made, or seem plausibly likely to be made in the next few decades, we are most unlikely to revert to the sort of good character test that was part of the 1898 scheme, or to impose new filial responsibility laws to push the responsibility for the elderly poor back onto families.

NZS has a number of pretty attractive features:

- It is administratively simple (near-universal schemes tend to be)

- It has contributed to New Zealand having one of the lowest elderly poverty rates in the OECD

- It focuses on a moderate level of basic needs, and leaves those with aspirations to a higher standard of living in retirement to save for themselves.

- Because it is not abated against other income there is no direct deterrent to people remaining in the workforce beyond 65 (and partly as a result New Zealand has relatively high voluntary labour force participation rates for people aged 65 and over).

- Because it is tied to earnings, at least in principle it avoids periodic battles over distribution of the gains from growth (which CPI indexed would tend to induce)

On the other hand, the scheme costs a lot of money, discourages some private savings (although there is no easy way of knowing if it discourages national savings), and seems to have a created a sense of entitlement . The availability of a near-universal income from 65 will discourage some labour force participation (itself a double-edged argument, since presumably no one wants infirm 85 year olds sent out to work), reducing average GDP per capita. The other double-edged feature is that there is no relationship at all between one’s ability to draw NZS and any contribution one may have made to the New Zealand tax system (whether as an individual or as part of a family).

I noted that NZS is expensive, and that cost is rising quite rapidly now each year, as the baby boomer generation reaches 65 and beyond. But high as the absolute cost is, it is worth bearing in mind that New Zealand’s public spending on pensions and other old age support is pretty low compared with that in other OECD countries. In 2011 only six of the 34 OECD countries spent a smaller share of GDP than New Zealand did.

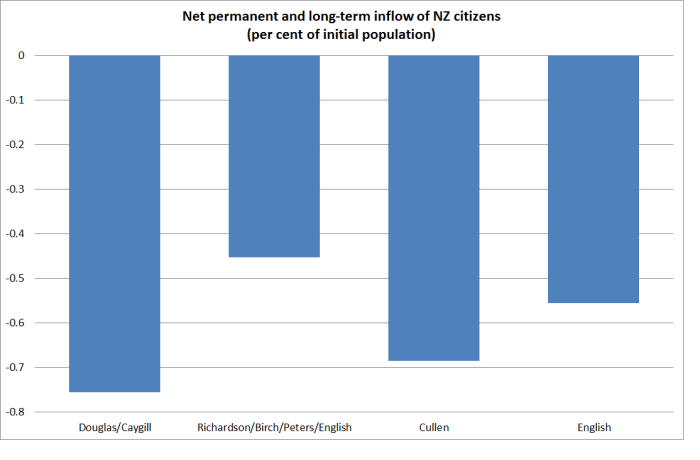

By contrast, in 1980 not only did New Zealand spend a larger share of its GDP than it did in 2011, but only six OECD countries then spent more. We made big changes after that – increasing the eligibility age back to 65, and lowering the payment as a share of income. Note that, despite the compulsory private savings scheme, Australia has been spending a little more on pensions etc than New Zealand does.

It isn’t a perfect system by any means, but I think it would be foolhardy to try to change the essential characteristics. Those old enough to remember 1984 (or even 1973) to 1999 will recall how intense the controversies were around superannuation, all for not really that much change in the end (from, say, the 1972 system to that prevailing after the late 1990s).

Reasonable people can differ on whether the appropriate formula is 66 per cent of wages, or something a bit lower. A case could be made for something lower (perhaps 60 per cent) but I also think it is a second or third order issue. Sure the direct fiscal costs are not trivial, but it is mostly a distributional choice about how generously, or otherwise, we want to treat the elderly. And even if some government was bold enough to lower NZS to 60 per cent of wages, it simply invites a future electoral auction, pushing the percentage back to (or even beyond) the current level.

The bigger issue surely is about the age of entitlement. In 1898 life expectancy at birth was around 57, so probably well under half of people reached 65 at all. Those who did still had a reasonable life expectancy, but rather less so than the life expectancy of the overwhelming bulk of the population who now live to 65. Not only are more people living to 65, and living for more years beyond 65, but the average health status of those who do is much higher than it was in earlier decades. And, in any case, fewer jobs now require hard physical labour. It all adds to a story which suggests that if society is going to provide a near-universal income for the elderly, “elderly” doesn’t, and shouldn’t, start at age 65. We’ve all heard the lines about 70 being the new 60 etc

If, as Brian Easton suggests, life expectancy at 65 is now five years longer than it was in 1898, perhaps we should be thinking of an NZS eligibility age nearer 70, especially as people typically enter the labour force much later in life than they were doing 100 years ago. In 1898 someone turning 65 would have spent 50 or more years in the fulltime labour force (or as spouse to someone in the paid labour force). Today, anyone graduating university or polytech will have spent 45 years at most in the fulltime paid labour force by 65.

Of course, one of the fruits of greater prosperity is the opportunity to consume more leisure, but in discussions around NZS we aren’t dealing with private preferences (eg to work fewer hours a week, take longer annual holidays, or to retire at 55) but about the basic state provision. It isn’t obvious why NZS should be available at an age much less than 70. Lifting the eligibility age over time to 70 would make a significant, and probably more enduring, contribution to easing the fiscal burden of public pensions. In addition to the direct savings, higher labour force participation among people aged 65-69 would lift tax revenues. Even health spending might be a little lower (people tend to remain in better health if they stay active longer).

These are difficult – but not impossible – issues for politicians to tackle, even though pretty much everyone knows that some change is coming. Partly for that reason, in contemplating any change in the next few years making the system robust to future changes in life expectancy is probably as important as whether NZS should cut in at 68 or 70. Life expectancy has been rising by around two years a decade, and public health alarmism notwithstanding there isn’t any sign of that changing yet. We shouldn’t need to struggle to revisit this issue every two decades Denmark has put in place a system of indexing the age of eligibility to changes in life expectancy – although it is fair to say that no such adjustment will be made until 2025.

But I think two more changes need to be made.

New Zealand has a high rate of inward migration. The target level of non-citizen immigration is around 1 per cent of the population per annum. Many of those people come to New Zealand young and will spending most of their working lives contributing to New Zealand and its tax system. But to collect a full rate of NZS you need only have lived in New Zealand for 10 years (at least 5 after the age of 50), so many people will be able to collect a full New Zealand pension having been in New Zealand for not much more than a quarter of a working life. New Zealand does enforce quite strict offset rules on those who have accumulated foreign pension entitlements, but many migrants now come from countries with little or no public provision of pensions. Surely it would make more sense to introduce a graduated scale – perhaps paying half the full NZS after 10 years residence, and a full rate only after someone has lived here for 30 years?

I had always assumed that New Zealanders who had emigrated to Australia in their hundreds of thousands over the last 40 years or so would be unlikely to come back to New Zealand when they were old, because they would have to live here for five years after age 50 before being eligible for NZS. I wasn’t the only one to assume that – I was corrected recently by a public servant doing some work in the area who had just discovered that residence in Australia (and several other countries with whom New Zealand has social security agreements) counts as residency in New Zealand for NZS purposes. It looks as though people can leave New Zealand at 20, spend an working life in Australia, accumulate significant private assets under the Australian compulsory private superannuation scheme (enough that they would not be eligible for the Australian age pension), and having cashed in those assets could return to New Zealand at 65, claiming a full rate of NZS never having worked, or paid tax, in New Zealand at all. Indeed, one might even be able to go on living in Australia. Perhaps I have misunderstood the rules, but this structure strikes me as pretty scandalous. What New Zealand public policy interest is served by such a generous universal approach to people who have not lived here for a very long time?

Personally, I’m happy that we should treat quite generously people who have spent most of their life in New Zealand and have reached an age that can genuinely be considered “elderly”[1], but I don’t feel the same sense of generosity towards those who have migrated here quite late in life, or to New Zealanders who have spent most of their working lives (and taxpaying years) abroad.

In a second-best world, I reckon NZS is a pretty good scheme. It costs government less than schemes in many other countries, it deters private savings and labour force participation less than most other advanced country schemes, and it largely avoids severe poverty among the elderly. But it isn’t a perfect scheme. I reckon politicians should be focusing on two areas:

- Progressively raising the age of eligibility (perhaps to 68 or 70), and indexing it to life expectancy changes

- Reducing the rate of NZS for those who have spent less than 30 years in New Zealand after the age of 20, whether naturalised New Zealanders (or migrant permanent residents) or native New Zealanders who have chosen to spend much of their working lives abroad.

[1] Or who may be genuinely physically unable to work.