Having now read the Financial Stability Report, and listened to the Governor’s press conference, I was surprised by the poor quality of the Report and of the policy that it discusses. The FSR is supposed to contain material to enable us to assess the effectiveness of their use of their powers (here and here). This one just does not.

Policy seems to be lurching from one intervention to the next, without any compelling analytical framework or evidence. There also appears to be little sign of any historical memory.

For example, only six months ago the Bank was reporting the results of its own stress tests, which suggested that the major New Zealand banks (and presumably the financial system) were resilient to even very severe shocks to asset prices and servicing capacity. And yet, despite announcing its intention to impose yet more, quite invasive, controls on bank lending to one sector of SMEs, there was no reference at all to this assessment and experience. Perhaps the Bank does not believe the results of the stress tests, but if not surely they it owe it to us to explain why. .

Similarly, the Bank laments that investors have become a larger share of property purchasers in Auckland (what is the “right” or “appropriate” share, and where is the “model” to determine that, we might reasonably ask them) but they don’t seem to see any connection between the imposition of the first LVR speed limit 18 months ago – which will have borne most heavily first-home buyers, who have always been those who relied most heavily on debt finance – and the greater presence of investors in the market. At the time their own analysis and modelling (eg see chart on page 9) made the point that potential buyers who were displaced would, over time, be replaced by other buyers. Their modelling also showed that the most that could be expected of the speed limit was a dip in house price inflation for a year or so, which would then be reversed as the new buyers entered the market.

If amnesia is a problem, so apparently is schizophrenia. On the one hand, the FSR and the press release tell us that “New Zealand’s financial system is sound and operating effectively”, but on the other hand they apparently think that banks are operating so recklessly that not a single Auckland investor purchaser should be able to take a loan of over 70 per cent of the value of the property, no matter how sound a proposition that borrower might otherwise appear to his/her lender (including their flow servicing capacity). Continuing the theme of an institution that can’t quite make up its mind – or perhaps doesn’t want to scare the investor horses, but wants cover for yet more regulatory interventions – the Governor told us in the press conference that he was becoming seriously concerned about financial stability risks. If so, perhaps the first sentence of the Report should have been written somewhat differently.

The Bank also doesn’t seem to display much regard for good process. It is going to produce a consultative document shortly on its proposals to restrict investor loans in Auckland (which I hope will have much more substantive justification for the proposed policy than is in the FSR), and yet it ‘‘expects banks to observe the spirit of the restrictions” now. “Consultation” is supposed to have substantive meaning, and not just around the fine details of the regulations. Is the Reserve Bank open to countervailing arguments, or has it already made up its mind and just going through the motions? If the latter, it might leave itself exposed to the risk of someone seeking judicial review.

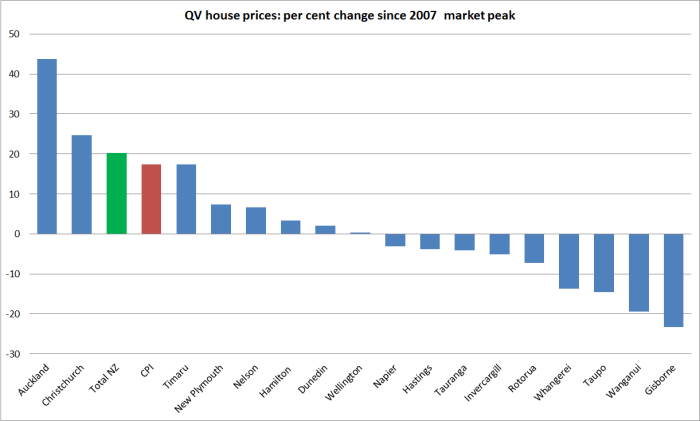

The Bank blunders in with these policies, each no doubt well-intentioned, but with little apparent recognition of the way that its actions affect real people, their lives and their businesses. 18 months ago a nationwide LVR speed limit was put in place, apparently because the Bank thought that house price inflation and associated credit growth was going to become a widespread problem. If the Bank was omniscient it might be one thing, but they were simply wrong. Ordinary house-buyers in Invercargill or Wanganui had to delay purchasing a house because of a mistaken Reserve Bank hunch. And these weren’t measures that were ever necessary – by contrast there will always be an interest rate in an economy – since large capital buffers were already in place. And in Auckland, the Reserve Bank’s earlier policy won’t have materially adversely affected those from upper income families, where parental support will have helped young people get around the 80 per cent limit. But what about those without wealthier parents, who are surely disproportionately Maori and Pacific? There was no hint of that distributive impact in the Regulatory Impact Statement for the earlier restriction. In Auckland the earlier restriction provided cheaper entry levels for the lucky (those who got inside the speed limit), the wealthy, investors, and cashed-up purchasers. Is that good public policy?

Who will be adversely affected and who will benefit this time? One group that springs to mind who might benefit are the fabled offshore investors. No one has any good idea how many of these people there are, but as Grant Spencer acknowledged in the press conference his regulatory restrictions won’t bear on them. From a financial stability perspective that might not matter to the Reserve Bank, but I suspect that to voters it will. First penalise first home buyers. Then penalise people looking to build a rental property business (and perhaps those who rent from them). And who will that leave? The middle-aged cashed-up purchasers, and any offshore purchasers. It doesn’t look fair, it doesn’t look like a reasonable use of Reserve Bank powers (when less intrusive instruments, such as risk weights and overall required capital ratios are available), and frankly it doesn’t look very democratic.

Of course, Parliament gave these powers to a single unelected official – although I doubt that anyone in 1989 ever envisaged them being used for such purposes. Jim Anderton, a staunch opponent of that Act, must now be rubbing his eyes in disbelief. And, on the other hand, the current government was supposedly committed to reducing the burden of regulation, not increasing it. One wonders if the Reserve Bank given much thought to the lobbying it now opens itself up to – carving out one set of rules for Auckland will, in time, open it to lobbying for special rules for other areas. Cashed-up purchasers wanting to buy more cheaply in Queenstown might be knocking on the Governor’s door before too long. If we must have regional policies (in bank regulation or other areas), let the choices be made by those whom we elect, and can toss out.

And then we are back with the larger questions.

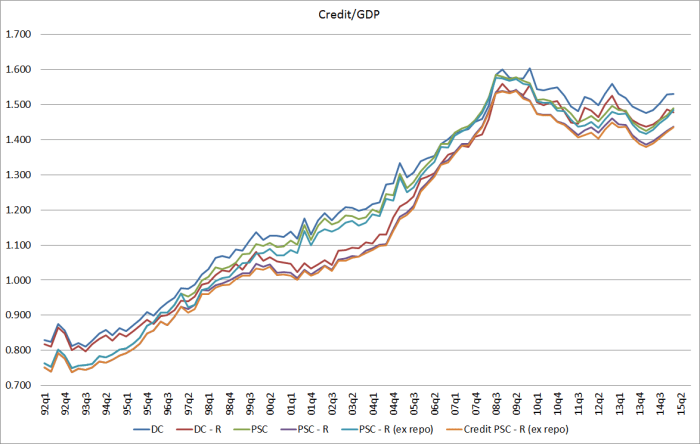

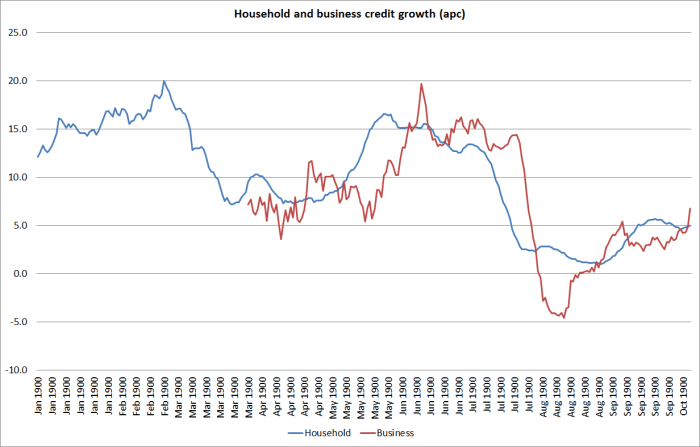

- Is there any evidence, from anywhere, ever, of a systemic financial crisis in a country where credit has been growing around the rate of growth of nominal GDP, and has been doing so for the last six or seven years? The Bank has produced some interesting new data on gross credit flows, but it doesn’t change the underlying evidence from the international literature: when credit is not growing fast relative to GDP one of the key risks of a future crisis is missing.

- Where is the evidence that loans to investors, all else equal, are riskier than other residential property loans? Repetition of the claim over and over again is not the same as evidence. As I have noted previously, the evidence from Ireland and the UK (tho in UK loan losses were always small) is not particularly enlightening, since the rush into buy-to-let properties was very much a late cycle phenomenon. None of the sources the Reserve Bank mentions look at losses on like for like (eg similar age, similar LVR) loans. In an earlier post, I questioned whether the Reserve Bank had any domestic evidence on losses on loans to investors, as compared to those to owner-occupiers, in those places where nominal house prices have fallen considerably in recent years. If there really is the sort of difference the Reserve Bank asserts, surely it should be showing up in New Zealand data. The one area where international evidence does seem to suggest that loan losses are greater is new house building – but the Reserve Bank is still carving that out from the limits.

One word that appeared very little in today’s document was “efficiency”. The Act talks repeatedly about the “soundness and efficiency” of the financial system. The efficiency references were put in for good reason – to limit the risk of recourse to direct controls, of the sort that plagued our system for decades. By almost any definition, somewhat arbitrary controls like the LVR speed limit and the proposed new Auckland investor lending limit impede the efficiency of the financial system. Almost inevitably there is some trade-off between soundness and efficiency considerations in any set of prudential measures, but in this document the Reserve Bank gives us nothing to allow us – or those paid to hold the Bank to account – to see how and why they have made the trade-offs they have. What basis is there, for example, for imposing a blanket ban of any investor loans in Auckland in excess of 70 per cent LVR[1] when, for example, the soundness of the system could have been protected at least as well – if there is a material threat at all – with, say, higher risk weights for Auckland property loans more generally, which would not skew the playing field between different classes of potential borrowers/purchasers at the whim of the Governor. There may be good grounds for the trade-off that is made, but they simply aren’t presented. How can people assess the effectiveness of the Bank’s exercise of its prudential powers?

Finally, the Bank partly justifies its targeted intervention in Auckland, against one class of potential buyers, on the basis of rental yields in Auckland. They argue that rental yields in much of the rest of the country are around 10 year average levels, but are at record lows in Auckland. But has the Bank looked at a chart of New Zealand bond yields recently? New Zealand 10 year bond yields are now at the lowest level probably ever (and certainly in the 30 years on the Reserve Bank’s website). And the market now expects that the Bank will have to cut the OCR not raise it. Shouldn’t we expect rental yields to bear some relationship to yields on alternative investments, such as long-term government bond yields. Of course, the Bank would no doubt defend its stance by reference to the abnormally low level of bond yields globally. And it is true that they are very low (while NZ’s remain high by cross-country comparison), but the Reserve Bank – even more than its overseas counterparts – has been getting the future path of interest rates wrong for six years now. Perhaps they will be right this time, but why should we be confident that they know better than the market?

It is difficult to fully make sense of what the Governor is up to. I suggested a few weeks ago that he didn’t want to be the person who presided over a NZ version of the US experience of 2006 onwards. Which would be a laudable goal if there were any evidence that circumstances were even remotely similar. But there isn’t: overall credit growth is subdued, the Bank presents no evidence of a systematic deterioration in lending standards, and fundamental factors provide a good basis to explain what is going on in house prices, both in Auckland and in the rest of the country. Perhaps the Governor just wants to “do his bit” to solve the problems in Auckland, but (a) the Reserve Bank has no statutory mandate to focus on trying to manage house price cycles, especially in a single city, and (b) it isn’t clear how impeding access to finance (in a climate of modest per capita housing turnover, modest volumes of mortgage approvals and modest overall credit growth) is going to in any sense help deal with the structural problem. There just isn’t a financial system problem – and if there is the Bank just hasn’t made its case, and should get the evidence out there – and it feels as if the Bank is misusing its extensive powers, based on a flawed reading of what is going on, and a failure to give due weight to how often past regulatory interventions have just made problems worse.

I pointed out a few weeks ago that it was now over a decade since the words “government failure” had appeared in a document on the website of the State Services Commission. The Reserve Bank is now a major regulatory agency, exercising more and more powers by the decision of single unelected official. I checked the Bank’s website, and the phrase “government failure” appeared only once (in a Bulletin article on historical crises), and “regulatory failure” appeared not at all. It should disconcert citizens – and those paid to hold the Bank to account – that there is not more evidence of the Bank having reflected seriously on what that entire literature, and the experience of countless other regulatory bodies, might mean for how they should exercise their powers.

PS In the press conference the Bank seemed to back away (perhaps just diplomatically) from the Deputy Governor’s expressed support for a capital gains tax. Almost a month ago, I lodged an OIA request for any material the Bank had considered on a CGT. Since the Bank has taken so long to respond, and is required by law to respond “as soon as reasonably practicable”, I’m assuming they must have a considerable amount of substantive material that needs review.

[1] And, on the other hand, no such restrictions in Christchurch even though the Governor observed that he thought a glut of houses in Christchurch was quite likely.