For months the Reserve Bank has promised us some insights on how they are thinking about options for unconventional monetary policy (for use if/when the limits of the OCR are reached). Last week they announced that they would release yesterday a principles document and that the Governor would deliver a short speech.

In this post I don’t want to concentrate on the substance of the material on unconventional monetary policy. It is quite troubling, especially when the limits of the OCR may well now be so close, but that will have to be the subject of another post.

In this post I want to concentrate on Orr’s comments about the immediate situation and the approach he and the MPC are taking to communication.

But first take a step back. It might seem like an age ago but it is only four weeks since the Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Statement. In that statement, and in the Governor’s press conference, the Monetary Policy Committee was really quite upbeat. Coronavirus effects – only around China – would be relatively small and pass quickly. In fact, the MPC was so upbeat they even moved to a very mild tightening bias. There was little serious analysis of the monetary policy risks and options – no analysis, for example, of past stark exogenous shocks and the monetary policy responses – including in the minutes of the MPC’s meeting. As I wrote at the time

There is no sense of the sort of models members were using to think about the issue and policy responses. There is no sense of the key arguments for and against immediate action and how and why members agreed or disagreed with each of those points. There is no sense of how the Bank balances risks, or of what they thought the downsides might have been to immediate action. There is no effective accountability, and there is no guidance towards the next meeting. Consistent with that, the document has one – large meaningless (in the face of extreme uncertainty) – central view on the coronavirus effects, but no alternative scenarios, even though this is a situation best suited to scenario based analysis. It is, frankly, a travesty of transparency, whether or not you or I happen to agree with the final OCR decision.

In fact, the projections (as usual) had been finalised a week before the final decision – that works fine often, but this was a very fast-moving situation.

And that was about it. There were no subsequent speeches from the Governor or his fellow MPC members, internal or external.

Since then, of course, a great deal has happened, little of it – at least in global terms – for the better, whether in terms of the progress of the virus itself, business confidence, or financial markets.

And yet the Governor told us he was coming along to give a high-level speech about longer-term monetary options. In his introduction to the written speech – all 19 pages of it – he went so far as to claim

Any perceived monetary policy signals in this speech are thus in the eyes of the reader only and not intended by the author.

But context and tone matter a great deal and often tell us a lot. And, in any case, it seems from various media accounts that Orr took questions at the little event he hosted to deliver the speech, and felt quite free in commenting on coronavirus and the place (or lack of it, as he saw it) for monetary policy.

That in iself, as a matter of process, was pretty appalling. We are told by an interest.co.nz journalist that Orr did not use his speech text, but instead

Calm vibes from Orr today as he delivered a 30min speech using hand-written notes

but no one who wasn’t there – and it was an invitation-only event – actually knows what he said, and what emphases he chose. That is bad enough re the speech itself, but then he ran a Q&A session for which there is no public record, other than snippets from various journalists’ accounts. On highly contentious, important, market sensitive issues that simply isn’t good enough – and just would not happen at any serious central bank. (In fact, the Bank itself knows better. Last year they did one of these self-hosted events with (a) an open invitation, and (b) video footage of the speech and Q&As posted on their website, and on that occasion the content was pretty innocuous.) Does the Monetary Policy Committee and the Bank’s Board – the latter paid to hold them to account – just roll over and go along with this travesty of good process? It appears so.

But, anyway, lets try to unpick what he said (and didn’t say) based on the fragmentary records we have.

First, the formal speech text – which must have been carefully considered and haggled over internally (at least if there is any decent process in place at the Bank, anyone willing to challenge the Governor). Here is the relevant section

The nature of the economic shock that authorities may be looking to mitigate will inform the choice of tools. A specific supply shock (where goods and services cannot be produced for some reason) may be better managed through fiscal support (both automatic stabilisers and/or targeted intervention), with monetary policy assisting rather than leading.

New Zealand’s current drought conditions in regions of the North Island provide an example of a supply shock. If the drought remains relatively region-specific, and/or short-lived, then monetary policy would have a very limited stabilisation role. Any resulting loss of production may be short-term, and automatic fiscal stabilisers and/or targeted government transfers and spending would be more effective at mitigating any broader economic disruption. Meanwhile, monetary policy would remain focused on any longer-term impacts on incomes and wealth, and hence inflation and employment pressures.

A similar set of considerations confronts policymakers globally at present with the spread of the Covid-19 virus. The eventual economic impact on global supply and demand will depend on the location, severity, and duration of the virus. The optimal mix of policy responses are driven by these same factors.

The severity in terms of disruption to economic activity depends on how the virus is contained and controlled, how long this will persist, and the collective response of governments, officials, consumers, and investors to these events.

The Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee will be picking through these supply and demand issues. We will need to account for international monetary and fiscal responses, financial market price changes (e.g., the exchange rate and yield curve), and domestic fiscal responses and intentions, to inform our response. We also remain in regular dialogue with the Treasury to assess how monetary and fiscal policy can be best coordinated.

We need to be considered and realistic as to how effective any potential change in the level of the OCR will be in buffering the New Zealand economy from shocks such as a lack of rainfall and the onset of a virus.

…

For us, these monetary policy and financial stability decisions are repeat processes as the duration and severity of events play out. We are in a sound starting position with inflation near our target mid-point, employment at its maximum sustainable level, already stimulatory monetary conditions, and a sound financial system.

Remember that this text is written knowing that the backdrop is the dramatically worsening coronavirus situation – it isn’t 200 cases in a faraway land anymore. He’s said nothing for weeks after an MPS that – at very least with the benefit of hindsight – didn’t really strike the right note. He’ll have known the market developments since – I’m thinking mostly of bond markets, but you can throw in equity markets and credit spreads too. He may not have had the ANZ Business Outlook data when he finalised the text, but if he was very surprised by the data – released an hour before the speech was given – that would be a very poor reflection on the Governor’s comprehension of just what is going on.

So all this was very deliberate conscious drafting, clearly designed to play down, to minimise, the coronavirus economic issues and the scale of the adverse demand shock that has been unfolding for weeks now. If a junior analyst had set it out this way, it would be one thing, but he is the Governor – people pay a lot of attention to his words, even if they are often “cheap talk”.

You see, droughts are something the Reserve Bank has never responded to. There isn’t even the sort of “longer-term” aspect for monetary policy he suggests – in fact, there is really is almost no longer-term dimension to monetary policy at all; discretionary monetary policy is designed to be about fairly short-term stabilisation. So to frame thinking about a monetary policy response to coronavirus in the same breath as droughts, ending

We need to be considered and realistic as to how effective any potential change in the level of the OCR will be in buffering the New Zealand economy from shocks such as a lack of rainfall and the onset of a virus.

and with not a mention of the risks around inflation expectations – which he was briefly rather good on for a month or so after last year’s unexpected 50 basis point cut – tells you this is someone looking for excuses not to adjust the OCR, minded not to do so if he could get away with it (which he probably can’t). A Governor (and MPC) who were seriously concerned – who recognised, for example, that most of what we’ve seen in New Zealand so far is a big adverse demand shock – doesn’t need to give away his hand on precisely how much the OCR might adjust, but would almost certainly phrase things differently than Orr did yesterday. It had the feel of a speech that he might have given a month ago. Then there might have been some excuses, but now there are none.

And then we turn to the fragmentary accounts of the actual delivered speech and the questions and answers. The journalist from interest.co.nz reports that

He said, in a speech delivered in Wellington on Tuesday, that the RBNZ won’t have a “knee-jerk reaction” to coronavirus.

He also said monetary policy was in a “support role”, with fiscal policy (government spending) being at the “frontline”.

“Knee-jerk reaction” is one of those lines you use when you disagree with someone’s call for action, and prefer to avoid engagement on substance. What Orr seems to think of as a “knee-jerk reaction” is (a) along the lines of the actions of the RBA and the Fed, and (b) what others would call bold and decisive leadership, or others still “just doing your job”.

As concerning is that next sentence. It isn’t his job to decide whether monetary or fiscal policy should be emphasised. His job is to take account of what he sees and act accordingly to contribute to stabilising the economy and supporting the eventual recovery. If the government chooses to do something large with fiscal policy – which there is no sign of yet – that is certainly something for the Bank to take into account. But as it is, no policy support – monetary or fiscal policy – has yet been given at all. Sure, the Bank can’t cut the 500bps or so that is typical in a New Zealand (or even US) recession, but their job – assigned by Parliament – is to respond strongly to severe adverse demand shocks, and big drops in short-term neutral interest rates, to help stabilise the economy and inflation expectations. As it is, nothing in the speech suggested any sort of strong lead from the Bank, let alone one that might very soon bring the unconventional tools into play. It is some combination of an abdication of responsibility and of the Governor’s long-held personal political preference – it has been backed by no analysis or research he’s produced, let alone by statute – for a more active, bigger government, fiscal policy.

We then got more of the same in response to questions

Orr said coronavirus posed a fiscal and monetary policy challenge, “but monetary policy will remain in that support role with fiscal policy being very much the frontline activity as it is now”.

“We will be watching very carefully for what is the important monetary policy response we need to make, but we want to do that in the best and fullest information, not some knee-jerk reaction, because New Zealand doesn’t need a knee-jerk reaction.

“We’re in a good space. I’m not sure a knee-jerk reaction would be particularly useful.”

Slogans rather than analysis, again. He’ll never have full information until it is far too late – monetary policy has to react to what is evident now and projections of what is coming. That is what it did in the past – responding to 9/11, to the 2011 earthquake, even to SARs – but Orr and the Committee never engage with any of this experience or practice.

Oh, and then the final bit from that account that caught my eye was this

“Confidence and cashflow will win the day,” Orr said.

Except that business confidence is through the floor – lowest since 2009 – and cashflow is rapidly drying up for many. Oh, and widespread social distancing, and all the economic costs and dislocation that entails, seems to be not far away at all. It is as if he was on another planet, where whistling to keep your spirits up was the remedy.

(Reflecting on the Bank’s apparent indifference to the severity of what is unfolding, and its threat to medium-term inflation expectations and nearer-term employment etc, I was reminded of how badly the Bank handled the period of the Asian crisis, as we were playing with the MCI. Many readers will be too young to really get the reference – count yourself lucky, but I must write it up one day – but the Governor will recall. He was there too.)

And what of the Herald’s account?

There we got this added snippet following the dismissive “knee-jerk” comments

We’re in a good space.

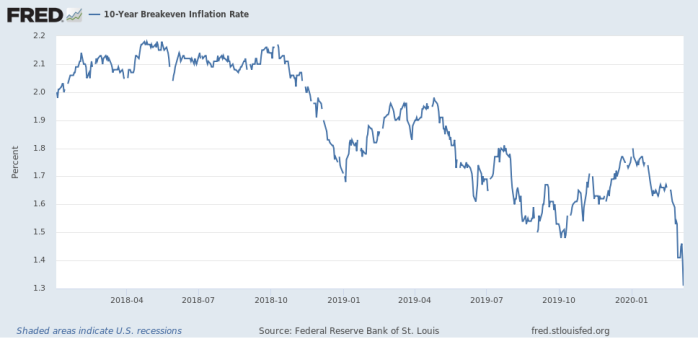

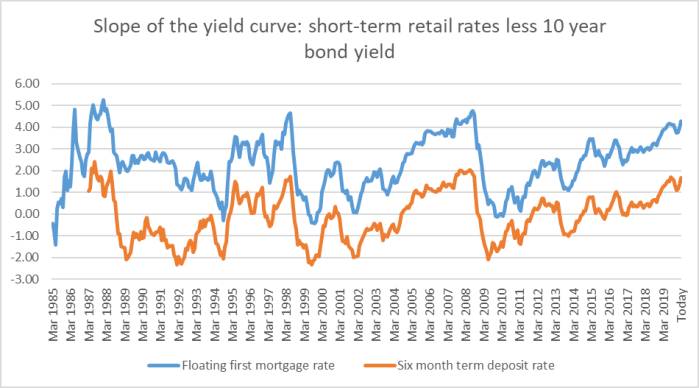

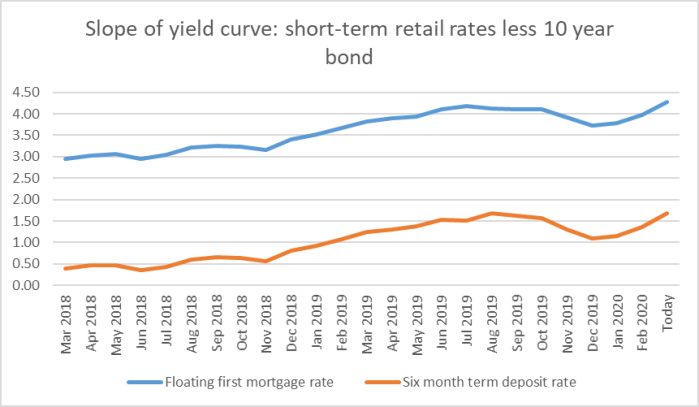

Who knows, perhaps he just meant that government debt is low. But there is no other way we can be thought of as “in a good space” to cope with a very sharp dislocation and loss of economic activity this year. And perhaps he hasn’t noticed that real interest rates – the ones people are paying/receiving – have been rising this year.

The Herald reports commentary from an economist who was invited to attend

“He basically hosed down expectations of a sizable interest rate cut and an inter-meeting one,” Bagrie, who attended the speech, said. “He explicitly said, time is on our side.”

It demonstrably isn’t. Does he have any conception of the exponential growth in case numbers, including in Australia with which we have a largely open border? Has he not noticed travel bookings drying up – still almost all a demand shock from a New Zealand perspective. This is one of those climates where time was never on anyone’s side – with hindsight (at least) action should have been in place weeks and weeks ago.

And a final quote

“Here in New Zealand we’re in this wonderful position where monetary policy is willing and able to do whatever matters, and fiscal policy is also in a strong and credible position [to respond].”

Except that from the Governor’s words and demonstrated behaviour – with his Committee sitting in front of him, unwilling to say anything, apparently in support – monetary policy is transfixed by the shock, doing nothing so far, and reluctant to do very much at all. Without even so much as a hint of what the risks and downsides the Bank has in mind if monetary policy was used aggressively while it still can be? I’m pretty sure there was almost no mention that one of the great things about monetary policy is that it can be quickly reversed when the need passes, and another is that it is really easy to implement, something that cannot be said for many of the fiscal schemes – details of which we have yet to see – that the Governor appears to so strongly favour, especially if/when the economic dislocation builds, people are sick and/or working from home, and firms and individuals across the economy are feeling the extent of the downturn, perhaps even a temporary shutdown, in the economy.

Fiscal policy isn’t the Governor’s job, although he needs to be aware of it and take it into account. Monetary policy is – his and the Committee, from whom we hear so little – and he simply isn’t doing it. It is an abdication of responsibility – reasons uncertain – that just confirms again his unfitness for the high office he holds. It also raises equally serious doubts about the rest of the Committee – I heard an extraordinary story yesterday of one external member scoffing at taking the economic effects of coronavirus seriously – and those paid to hold them to account.

It reflects pretty poorly on the Minister of Finance too. After all, the MPC is wholly his creation, and he has legal responsibility for the way they do (or don’t) their job. And he is the only one in all this with any serious public accountability.

I’m going to leave you with one of the Governor’s good moments. These words were in a speech he gave in San Francisco last year

In particular, it is now more suitable for us to take a risk-management approach. In short, this means we look to minimise our regrets. We would rather act quickly and decisively, with a risk that we are too effective, than do too little, too late, and see conditions worsen. This approach was visible in our August OCR decision when we cut the rate by 50 basis points. It was clear that providing more stimulus sooner held little risk of overshooting our objectives—whereas holding the OCR flat ran the risk of needing to provide significantly more stimulus later.

You have to wonder what about the world has changed that, in the Bank’s view, makes that sort of approach not the best way forward now – when the downside risks are much starker and clearer than they were then.

My bottom line on the Governor is that he will probably do the right thing eventually, after toying with or trying all the alternatives. The global situation looks set to get quite a bit worse in the days before the OCR review, and I suspect the MPC will find themselves finally mugged by reality, overwhelmed by events. But we need, deserve, a better central bank, a better MPC, a better Governor, than this. After all, as he says, confidence matters, and it is hard for anyone to have much confidence in him, or to count on his words meaning anything from one week to the next.

UPDATE: And here were the quotes I couldn’t find quickly this morning re inflation expectations. He was very concerned to hold them up then, but apparently much less so now when the substantive risks are so much greater.