One can debate whether or not the Reserve Bank should have cut or not. Reasonable people can differ on that. But their communications quite clearly needs (a lot of) work. This post is just one illustrative example of the sort of problem there is: the role of inflation expectations in their thinking and public commentary.

Back in the August Monetary Policy Statement – the one where they announced the rather panicked 50 basis point cut, not really consistent with either the rest of the document or their own numbers – there wasn’t much mention of inflation expectations. To be specific:

- they are not mentioned at all in chapter 1, the main policy assessment/OCR announcement,

- they are mentioned more or less in passing in the minutes, viz

Some members noted that survey measures of short-term inflation expectations in New Zealand had declined recently. Others were encouraged that longer-term expectations remained anchored at close to 2 percent.

with no suggestion that it was a significant part of the story

- of the seven other references in the document, five are simply labels of charts, and one was in the standard descriptive framework section (“how we do monetary policy”). The only other substantive reference was pretty unbothered.

Although survey measures suggest inflation expectations remain anchored at around 2 percent, firms and households continue to reflect past low inflation in

their pricing decisions.

If that had been all, a reasonable reader might have assumed expectations measures were something they were keeping an eye on, but weren’t much of a concern, or playing much of a role in the OCR decision.

But in his press conference, we got the first hint of a quite different line. Perhaps the Governor genuinely felt differently than the majority of the MPC – which frankly seems unlikely, given that he chairs the committee and he and has staff have a majority on it – or perhaps he was simply casting around, more or less on the spur of the moment, for reasons to justify cutting by 50 basis points rather than the 25 points everyone had expected (50 point moves not having been used since the height of the 08/09 recession).

But whatever the reason, in answer to a question (just after the 10 minute mark here) he made the following points:

- they’d tossed and turned between going 50 points then, or 25 points then and 25 later and,

- over recent days they had become increasingly convinced that doing more sooner was a safer strategy to achieve their targets than a strategy of going more slowly over a longer period. He went on to note that

- it was all about the least regrets analysis and stated that in a year’s time he would much prefer to have the quality problem of inflation expectations getting away on us, and possibly having to think about “other activity” [ tightening?]

- that was preferable (better/nicer) than finding a year hence that they had done too little too late.

I was quite taken with those comments at the time, and commented positively on them in my own review of that MPS. It seemed exactly the right way to think about things, especially as in the same press conference he was highlighting the risks of the OCR having to go negative (the more that could be done now to boost expectations, the less likely the exhaustion of conventional monetary policy capacity).

But do note that none of that “least regrets” perspective was reflected in the MPC minutes.

The Governor obviously took something of a fancy to this line. In a interview with Bernard Hickey a few days later, of which we have the full transcript, he is quoted thus

“Doing the 50 points cut was interesting: whilst you get closer to zero, you also shift the probability of going below zero further away,” Orr said.

and

We’ve spent a lot of time around, I suppose, regret analysis, and I spoke about – you know, in a year’s time looking back, thinking ‘well, I wish I had done what?’ And I thought it’s – I would far prefer – and the committee agreed – far prefer to have the quality problem of inflation expectations starting to rise and us having to start thinking about re-normalizing interest rates back to, you know, something far more positive than where they are now. And that would be, you know, it would be a wonderful place to have regret relative to the alternative: which would be where inflation expectations keep grinding down.

and a few days later, in a speech given in Japan, the Assistant Governor was also now running this message (emphasis added)

A key part of the final consensus decision to cut the OCR by 50 basis points to 1.0 percent was that the larger initial monetary stimulus would best ensure the Committee continues to meet its inflation and employment objectives. In particular, it would demonstrate our ongoing commitment to ensure inflation increases to the mid-point of the target. This commitment would support a lift in inflation expectations and thus an eventual impact on actual inflation.

On balance, we judged that it would be better to do too much too early, than do too little too late. The alternative approach risked inflation remaining stubbornly below target, with little room to lift inflation expectations later with conventional tools in the face of a downside shock. By contrast, a more decisive action now gave inflation the best chance to lift earlier, reducing the probability that unconventional tools would be needed in the response to any future adverse shock.

I commented positively on that too. It was good orthodox stuff.

And it kept coming. In an interview with the Australian Financial Review, at Jackson Hole, a few days later, here was Orr

Q Was this [falling world rates][ front of mind when you did your recent interest rate cut?

A. It was front of mind. Without doubt the single biggest….one [factor] was domestic. We saw our inflation expectations starting to decline and we didn’t want to be behind the curve. We want to keep inflation expectations positive- near the centre of the band.

And it was also referred to in passing in the folksy piece the Governor put out back here that week, noting “lower inflation expectations” as second in the list of influences on the OCR decision.

And here it was again in the Governor’s 26 September speech

We also judged that it would be better to move early and large, rather than risk doing too little too late. A more tentative easing of monetary policy risked inflation expectations remaining stubbornly below our inflation target, making our work that much more difficult in the future.

By this point – less than two months ago – any reasonable observer would have been taking note.

So what had actually happened to inflation expectations by this point? At the time of the August MPS the Bank already knew that the 2 year ahead expectations had fallen quite a bit – from 2.01 per cent to 1.86 per cent in a single quarter. That’s not huge, but it is not nothing either, and with core inflation still below 2 per cent it wasn’t something the Bank should have been that comfortable with. The year ahead measure (noisier) had dropped by more.

As it happens, the other main inflation expectations survey – the ANZ’s year ahead measure – hadn’t dropped at all by the time the Bank acted in August: from May to July year ahead expectations were in a 1.8 to 1.9 per cent range. In August – but not published until 29 August – they fell to 1.7 per cent, and over the last couple of months they’ve fallen a bit further, the latest observation being 1.62 per cent.

As for the RB survey, there was also a slight further drop in mean expectations in the latest survey that was released on Tuesday (but which the Bank had in hand throughout its November MPS deliberations).

Both the latest ANZ and latest RB surveys were completed exclusively in the period well after the Bank’s surprise 50 point cut in August. If the Governor (and Hawkesby) were serious about that rhetoric they’d surely have hoped to have seen at least some bounce in the latest survey – after all, that was the logic of preferring a big cut early. Instead, those survey measures fell a bit further (not to perilous levels of course – in fact, current levels are just consistent with where core inflation has been for some time, a bit below the target midpoint).

During the Wheeler/McDermott years the Reserve Bank rarely if ever mentioned the market implied inflation expectations, calculated as the breakeven rate between indexed and nominal government bond yields. I used to bore readers pointing out this curious omission – they never even explained why they felt safe totally discarding this indicator.

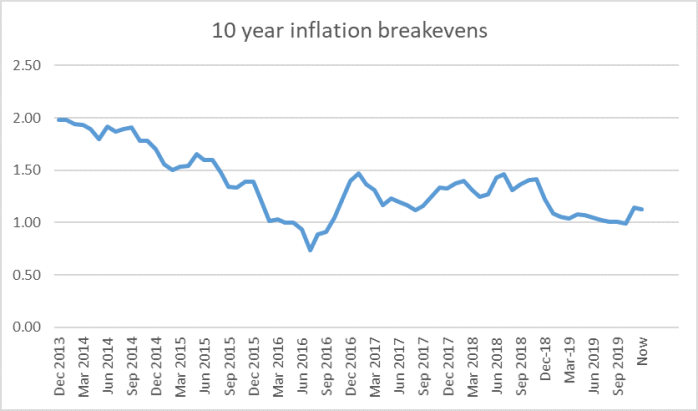

Inflation breakevens have been below 1.5 per cent now consistently for four years now and fell further this year. In recent months, those implied expectations – average inflation expectations for the coming 10 years – were just on 1 per cent. In monthly average terms, the low point wasn’t even July/August (ie just prior to the MPC’s bold action) but October.

Here is the chart, monthly averages but with the last observation being today’s.

As the Governor was very keen to point out yesterday, there has been a small lift in this measure……but he was less keen to mention the level; the small lift only takes the breakeven rate back to aroud 1.13 per cent. This time last year it was 1.41 per cent, still miles below the target midpoint. Perhaps the recent lift will be sustained – we should hope so – but on any reasonable balancing of survey and market measures you could really only say things hadn’t got worse over the period since August. On the clear words of the Governor and Assistant Governor, it was quite reasonable for analysts/markets to look at the inflation expectations data and expect it to feature prominently in this week’s MPS – after all the merits of the Governor’s August/September arguments (agree with them or not) hadn’t changed, expectations hadn’t lifted, and the Bank had given no hint they’d changed their way of thinking, yet again.

But what did the MPC have to say about inflation expectations on Wednesday? Again there was nothing at all in the chapter 1 policy assessment/announcement, and there was just this in the minutes

The Committee also noted the slight decline in one- and two-year ahead survey measures of inflation expectations. Nevertheless, long-term inflation expectations remain anchored at close to the 2 percent target mid-point and market measures of inflation expectations have increased from their recent lows.

They were pretty half-hearted, even about those market breakevens. No mention at all of the arguments the Governor and Assistant Governor were running only a couple of months ago, and although the minutes do now mention the idea of least regrets this was all they said

In terms of least regrets, the Committee discussed the relative benefits of inflation ending up in the upper half of the target range relative to being persistently below 2 percent.

The Governor’s comments in August certainly suggested he’d have thought it better then to run the risk of being a bit above 2 per cent (after a decade below). But this time, the Bank as a whole has reverted back to the cautious approach the Governor was looking unfavourably on, in public, only three months ago. We are back to “oh well, never mind”, or so it seems, and all that pre-emptive talk, doing what they can to minimise the risk of needing to go below zero, is supposed to disappear down the memory hole?

It seems all too symptomatic of what is wrong with the way the Bank is conducting monetary policy at present. There are few/no substantive speeches, the minutes capture little of the flavour of thinking, half the MPC members are simply never heard from (and no one knows if they have any clout or not), there is no personalised accountability (as a market commenter here noted, it is incredible that no one on the Committee was willing to record a dissent yesterday, all hiding behind the Governor)….and then we get the Governor just making up policy rationales (quite sensible ones in this case) on the fly, only to then jettison them, without explanation or a chain of articulated thought, when for some reason (still unknown) they no longer support his instincts.

Was it ever an approved MPC line? If not, why was the Governor just making up stuff – and then repeating it several times in open fora? Under the rules he is supposed to be the spokesman for the whole committee. And if it was an approved line why (a) did it never make it into the MPS, and (b) why has the MPC now changed its thinking when there is no sign of significant rebound in expectations, the effective lower bound is still in view, and the domestic measures have actually been drifting lower?

There is little basis for observers and markets to make any reliable sense of the MPC. We know little, that is in any way consistent, about their reaction functions, their loss functions, their models, or even their stories about what is going on locally and internationally. Big surprises, of the sort we’ve had in New Zealand at the last two MPSs, have become quite uncommon internationally, and that is generally a good thing. Where are we now – 18 months into the Orr governorship, 7 months into the new MPC – simply isn’t good enough The reforms the government initiated last year could have been the opportunity for something genuinely much better. Instead all we seem to get is a bit more expense – all those high fees for the silent, invisible, and unaccountable externals.

Monetary policy isn’t being handled well, and neither is bank supervision (bank capital and all that). Together, these twin failings in the Bank’s two main functions paint the Bank and the Governor – and those responsibe for holding them to account in a pretty poor light. There are hints that, under pressure, the Governor may have recently toned down his act and started to operate a bit more professionally. If so, it would not be before time, but if this week was anything to go by the tone may be a bit better but the substance of the messaging and communications still leaves a lot to be desired. At present, the best guess (sadly) would be on another lurch, in an unpredictable direction, relying on new arguments plucked fresh from the air, with no one certain quite who they represent or how long they will last.

Hardly surprising from Orr, his messaging around being transparent and open shadows that of the current labour government. Are we missing the fact that we have an election year coming up in 2020 and that the governor and labour may want some bullets for that?

LikeLike

This Labour/NZfirst/Greens government is corrupt. A little bird mentioned to me that the Port move from Auckland to Northland report conclusions was already written and the so called independent experts were told to just fill in the blanks, sign the report and get paid. They want to win the next election and this corrupt manipulation of independent reports with a $10 billion bribe to win the Northland electoral seat for NZfirst must make NZ one of the most corrupt countries in the world in 2019/2020.

LikeLike

Orr is like that show-off kid who always wants to be noticed!

LikeLike

Orr has certainly toned back and have shown much more restraint on his RBNZ Mahutu referenced arrogance. But Labour ministers and NZFirst ministers are increasingly being rather abusive and arrogant to the publics concerns.

Anyway nothing wrong with placards pointing out Jacinda Ardern as a liar. Thats the truth and she should face the fact that she is the most blatant and regular liar we have ever had as a Prime Minister. A lie pops out of her mouth everytime she opens it.

LikeLike

“One can debate whether or not the Reserve Bank should have cut or not. Reasonable people can differ on that.”

Can I offer some thoughts on reasons why the Bank may have not cut, and to me at least why this made sense

* They want to wait and evaluate how the last cuts, particularly the 50bps one, flow through the economy.

* There is no point in cutting again if all it does is kick off another round of house price inflation. (This is a real possibility with signs already emerging (including in the RBNZ survey) and I’m curious why you would appear unconcerned about that happening such as to not even mention it as a risk.)

* The last cut had the opposite effect to what they wanted, scaring people that a recession was imminent.

* Interest rates are not constraining business investment and another 0.25bps will not make any real difference to business investment (the BNZ commentators have been articulating this argument for a while, very clearly, backing it up with what their business customers are telling them https://www.bnz.co.nz/assets/markets/research/191108-MPS-Preview.pdf). But dropping the rate could affect the housing market.

* The lower the prevailing OCR, potentially the potency of monetary policy effected through standard means will be weaker (I know this is debatable but it nonetheless seems intuitive.)

* While you looked at a “core” measure of non-tradable inflation you ignored the headline non-tradable measure, which having been steady at around 2.8 (!) percent for the last nine months has now increased to 3.2 percent. This is significant, and to me the Bank should be cutting interest rates when non-tradable inflation, the kind that doesn’t face international competition, is at these levels and rising.

* It is better to be on the underside of the midpoint than the overside (from the MPS notes). Higher inflation is more harmful than lower inflation and makes us less competitive, does your view differ? In one of your earlier posts you said “there was a (welcome and overdue) pick-up in inflation a couple of years ago?” What rate of inflation in your view would suggest an increase in the OCR was warranted?

LikeLike

“…and to me the Bank should NOT be cutting interest rates when non-tradable inflation…, is at these levels and rising.

LikeLike