There was a thoughtful short piece in the BNZ’s weekly commentary yesterday on economic prospects for the next few years. Perhaps there are others around that I missed – I only heard of this one when my son drew this report of it to my attention

BNZ’s head of research Stephen Toplis is warning that economic activity won’t return to pre-crisis levels till some time in 2023, while unemployment might not get back below 5% before 2025.

I gulped. I hadn’t quite thought about it in those specific terms. But as I did, I realised it probably wasn’t an implausible story (as Toplis notes in his piece, and as everyone must, precise numbers/forecasts have little meaning at present; the issue is more about broad orders of magnitude and the nature of the supporting story).

Toplis’s own short-term story seemed, if anything, insufficiently bleak, although he may just have been making the point that however optimistic you are about restrictions, the virus etc, a big slump in GDP is inevitable (much has already happened, if you think of week by week GDP). And even if one assumes, as BNZ guesstimates, that two-thirds are people are still working (at home or essential on-site), many of those will be working at much lower rates of productivity than in normal times (how many people who notionally should be able to work from home actually can’t, whether because of kids or no work laptop or…?), and in many firms/agencies demand for services will be lower even if supply could be maintained from home.

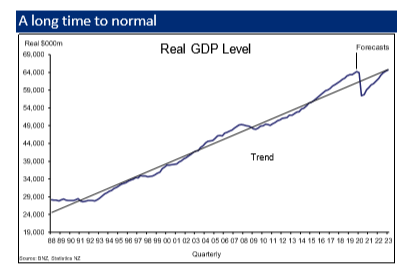

These are his two charts, first GDP

and unemployment

It would be staggering if the unemployment rate stays below the early 1990s peak, but the real issue – and the focus of Toplis’s commentary – is the rate of recovery. On his telling, if something like 5 per cent is our NAIRU, we don’t get there even in 2025. (And don’t forget the underemployment rate: people who have some work, but really want more hours.)

As Toplis’s chart suggests, it is easy to envisage a quick snap-back to a considerable extent in some areas. If people haven’t bought clothes for (say) six months, there will be significant sales next spring/summer. But that initial bit of recovery is the easy bit. In his note, Toplis articulates lots of mostly plausible reasons why anything like a full recovery will, almost certainly, be slow, here and (no doubt) abroad. One thing I noticed is that he hardly mentioned the role of macroeconomic policy, usually vital in helping economies back towards full employment after any serious dislocation.

One can’t cover everything in a short note, but it is possible macro policy will be hamstrung in the (eventual) recovery period. If the Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee simply refuses to cut interest rates, and the government lets them get away with it, we will probably have rising real interest rates heading into a recovery (notice the 0.4 percentage point slump in inflation expectations in the ANZ survey released this afternoon, before the sheer scale of the economic shock had really begun to dawn). As for fiscal policy, a great deal with be done in the slump itself, but you have to wonder just how ready voters and taxpayers will be to see new large commitments into the indefinite future, potentially at times when (as in the BNZ charts) things are much less bad than at the bottom, even if not that good at all. This has been my worry about using fiscal policy too soon in all my writings in recent years about the risk of the next recession. At present, of course, the fiscal taps are open wide – and rightly so – but the tolerance of that won’t last forever. It never has anywhere else, any time else (and, for what it is worth, fiscal stimulus into the recovery will – all else equal – push up the real exchange rate, the very last thing this economy is likely to need.)

Which is partly by way of a long prelude to a point that I think needs to be recognised not just superficially but at a much more profound level across the country, and in particular in debates around appropriate economic policy responses. There is no possibility now of simply hibernating for a couple of months only to reawaken and pick up where we left off at the end of the summer holidays. It was a tempting way to frame things in the early days and weeks, and to greater degree or less was probably part of the way almost all of us thought. It was the sort of conception that seemed to have been in mind when the government began shaping its first assistance package a month or so back.

But it simply isn’t a helpful or relevant way of framing the challenges now. And policymakers – and those advising them (and we have seen precisely none of The Treasury’s advice) – need to stop working on that outdated, if understandable, view.

Perhaps there is still some limited applicability of that model for the businesses that have only been savagely affected by the government’s partial lockdown. If there were this magic world in which four weeks hence, the partial lockdown would be lifted and domestic life go back to normal, with certainty that regime would endure, then perhaps there would still be a role for assistance explicitly premised on keeping existing firms together. (Especially as while closing, say, the Island Bay Butcher might have been good public health policy, but it was also still a straight regulatory taking, for which there could be good grounds for pure compensation.)

But everyone knows that isn’t the real world. Even if partial lockdowns are eased, they may come back. And no one supposes we are quickly going back even to normal domestic life, or with any degree of certainty. As for large chunks of the outward-oriented sectors, no one knows when people will be (a) able and (b) in large numbers willing to travel. Every business owner and manager either recognises this outlook, or should be now in the process of working it out.

And, although the government knows more about its strategy (if there is one – David Skegg this morning being the latest to cast doubt on that) than we do – although even that is mostly because they’ve not been at all transparent in releasing advice, Cabinet papers etc – in reality they really don’t know much more than any of us. Facts will surprise, public pressure will surprise, and even if there is a strategy now, it may well change faced with future reality (that isn’t a criticism, it is just the nature of things).

And so government policies shouldn’t be based on some particular vision or dream of what the economy should or might look like – except perhaps being supportive of getting back to full employment just as quickly as possible. Although there may be some practical advantages in getting short-term income support to households via current employers (it is not clear quite what those advantages are, unless MSD is truly overloaded), we shouldn’t be attempting to design packages that attempt to lock in place existing firms, existing industries. But that is still the tendency/temptation in too many places, including in the latest Australian package yesterday.

It is also why I still think that my “ACC for the whole economy for one year” model is the best conceptual framework around which to organise support and assistance.

Recall the key dimensions from a couple of earlier posts:

- Parliament would legislate urgently (preferably, or the guarantee powers in the Public Finance Act would be used) to guarantee that every tax-resident firm and individual in the coming year would have net income at least 80 per cent of their net taxable income in the previous year (loosely the 2019/20 and 2020/21 tax years, but of course the slump will already have been serious this month),

- the guarantee would be restricted to a single year (Parliament and the Minister can’t bind themselves not to extend, but the framing would be a one-year commitment),

- it is a no-fault no-favourites approach. My taxes have to prop up Sky City just as yours will have to support people/firms you really can’t stand. Picking favourites is a recipe for corroding trust and the willingness of the public to see the public purse used responsibly to get us through the next few years,

- since the guarantee would be legally binding, and structured to be assignable, financial institutions should generally be willing to extend credit on the security of the guarantee (they don’t need the cash upfront, just the assurance that the Crown can’t really walk away). This is primarily relevant to businesses, given the ‘mortgage holiday’ banks have already agreed,

- the guarantee need not displace actual immediate income support measures, designed to get cash in the pockets of households now (rather any such state payments would be factored in when everything was squared up at the time of next year’s tax return), but especially if you are in lockdown and any mortgage commitments are deferred, high levels of immediate cash are less an issue than usual (not much to spend cash on).

- for firms, the guarantee would not be conditioned on any commitment to stay in business. In you are a heavily indebted tour operator in Rotorua and you think it will be three years until “normality” returns, walking away (closing down) now may well make a lot of sense. The 80 per cent guarantee for one year is simply a buffer, that limits the downside for the first year, and buys some time both for the business(owners) and their financiers. For some, however, it will be enough to give them time, and access to credit, to get their firm to a scale best suited to being able to come back. But that needs to be their judgement, and that of financiers, not a template imposed from Wellington.

- for individuals, the income guarantee will also help to underpin public support/tolerance for whatever restrictions remain in place for an extended period. In addition, I quite liked the idea the New Zealand Initiative put forward the other day (of allowing people to borrow – capped amounts – directly from the Crown, akin to a student loan, with income-contingent future repayments) and also like Michael Littlewood’s proposal – akin to what has already been done in Australia – of allowing people easy access to a capped portion of their Kiwisaver funds, it being after all their own money, and times being very tough. (KiwiSaver and COVID Littlewood)

- there might be merit, fiscally and from a fairness perspective, in considering supplementing the downside guarantee with a one-year special additional tax on any 2020/2021 earnings more than 120 per cent of the previous year (there wouldn’t be much revenue in it, and it plays no stabilisation role, but there might be an appealing political/social symmetry).

The key pushback against my proposal is the expense. My view is that that particular concern is overdone, and that the likely cost would not be unsustainable (and quite a bit of it it is already being spent anyway, in measures announced so far).

GDP last year was $311 billion dollars. Since I only propose guaranteeing 80 per cent of the previous year’s net income, it is only if aggregate GDP drops by more than 20 per cent for the full year that the numbers start getting large at all (there will be expense well before that because many people – notably public servants, and those in some “essential industries” – will face no hit to wages or profits, while others are already experiencing huge losses. Suppose that full-year GDP fell by even 30 per cent – larger than any guesstimate I’ve seen, although who knows what next week will bring- and you still looking at an overall fiscal cost that should be no more than perhaps 20 per cent of GDP. That simply isn’t an unbearable burden for a country that had net general government financial liabilities last year (OECD measure) of 0 per cent of GDP (no, no typo there, zero).

Perhaps some readers will look at this idea and go “nice idea, but aren’t we better saving our fiscal capacity – including political tolerance for more fiscal support – for after the crisis is over; after all, no one knows how long that will be”. I guess my response is that

- monetary policy, including the exchange rate, can do most of the recovery work, if it is allowed to be used aggressively, and

- this is the sort of pandemic national self-insurance policy we might have voted to put in place 20 years ago, if we’d thought hard about the risks (and private insurance really isn’t an option; even if the policies existed, in a severe enough crisis, there will be systemic failure of insurers). We are each eligible to draw from the national pool, no questions asked, as a one-year buffer (another way of thinking of it is as akin to redundancy pay or income protection insurance). In fact, one could reasonably argue it was, at least implicitly, the policy we did set up, without quite being explicit about it, in choosing to run consistently low levels of debt, always citing our vulnerability to natural disasters etc (even if pandemics weren’t front of brain most of that time). It is about a buffer, buying time to learn more, explore options etc, without locking anyone (firms or households) into arrangements/relationship that just might not be sensible again any time soon.

If something like this isn’t done soon, a rapidly growing number of firms will simply fail/close. The extreme uncertainty combined with the extreme revenue losses will leave too many thinking they have no realistic choice. And the government shows all the signs of helping the bigger and more prominent firms – perhaps even less generously than I’ve suggested here, but in ways that could deeply sour public sympathy for doing anything much, and undermine any sense that the government is treating people and firms in a way that will perceived as fair and equitable.