I’ve been working on a review of an interesting new book by an American academic, Peter Conti-Brown, with a background in law and financial history, on reforming the governance of the US Federal Reserve System. The Power and Independence of the Federal Reserve is a funny mix of a book. At a time, in the years following the 2008/09 financial crisis, when all sorts of people from different parts of the political spectrum have concerns about the Fed – be it concerns about the influence of bankers, unease about the quasi-fiscal choices the “technocratic” central bank has been making, pushes to “audit the Fed” and so on – the author sets out to aim for a pretty broad audience. It isn’t just an academic tract – he clearly hopes to be read by think-tankers, Congressional staffers and intelligent voters who perhaps have a vague sense that “something is wrong”. It is difficult to imagine an equivalent book in New Zealand selling more than 100 copies. There are some advantages to size.

There is the odd amusing story to spice up the text. Picture the early Board members of the Fed worrying about where they would rank in the official US order of protocol. Unimpressed at the State Department’s ruling that they would “sit in line with the other independent commissions in chronological order of their legislative creation” they escalated the matter all the way to Woodrow Wilson. The President, clearly unimpressed with the pretensions of the Board members, told his Treasury Secretary “well, they might come right after the fire department”. The State Department ruling stood – in order of precedence, Fed Board members ranked behind the board of the Smithsonian.

One of Conti-Brown’s key themes is that if laws matter, and of course they do, individuals and the intellectual climate of the times matters more. He devotes quite a lot of space to illustrating how, with largely unchanged legislation, the conception of the Fed, and the relationship between it and politicians (especially Presidents), has changed markedly over the decades. (A somewhat similar story might be told about the Reserve Bank of Australia, over its rather shorter history.) Marriner Eccles – chair of the Fed under Franklin Roosevelt – saw the role of the Fed as being to work hand in glove with the Administration. The modern conception of an operationally independent central bank is very different – perhaps especially in the US where the Administration has no role in setting policy targets (unlike, say, the UK or New Zealand).

Of course, the notion that individuals matter shouldn’t really be a stunning insight. But much of the modern notion of an operationally independent central bank rests of the implicit view that there are technocratic answers to the problems we delegate to central bankers. If so, then it really shouldn’t matter much which technocrat holds the key job(s) at the central bank. That view was near-explicit in the way the New Zealand framework was set up: set the goal clearly enough, and make the Governor dismissable if he fails, and pretty much anyone will do.

Life – macroeconomics, and financial regulation – isn’t like that. Central bankers and financial regulators make choices, especially (but not only) in crises and, whatever the relevant legislation says, the values, ideologies and experiences of those who hold decision-making powers will matter, at times quite a lot.

And so much of Conti-Brown’s book is, in effect, around appointment and dismissal procedures for key positions in the Fed. He is particularly exercised about the positions of the heads of the regional Feds, and indeed of the regional Federal Reserve Banks themselves (“we get a sense [from past Congressional testimony] that nobody knew exactly how to define these strange quasi-private quasi-public structures”).

The US Constitution itself has an appointments clause. “Officers of the United States” can only be appointed by the President with the “advice and consent” of the Senate. There is an exception for “inferior officers”, for whom Congress may specify that the President alone or the head of an agency (him or herself a principal officer, appointed by the President with Senate advice and consent) may make the appointment. Members of the Fed’s Board of Governors are “principal officers” and are subject to Senate confirmation. The President can also dismiss principal officers, but the courts have also ruled that, for independent agencies such as the Fed, the President cannot dismiss a principal officer at will (eg just for policy differences).

Regional Fed presidents, who exercise what looks like considerable authority as rotating members of the FOMC, are not appointed by the President, do not face Senate scrutiny, and are also not appointed (or dismissable, even for cause) by people who are themselves principal officers. In Conti-Brown’s words “the Reserve Banks and FOMC, as currently governed, are unconstitutional, The separation between the US president and the Reserve Bank presidents is simply too great”.

Conti-Brown argues that the role of the regional Presidents, and their relationship with the rest of the system, should be markedly changed. He proposes putting the Board of Governors clearly in charge, giving them exclusive responsibility for the appointment and dismissal of regional Presidents, and effectively reducing the regional Feds to no more than branch offices. In his model, the regional Fed Presidents would all be removed from the FOMC, except as (in effect) senior staff observers, so that all monetary policy decisions will have been made only by people selected by the President, and subject to the Senate advice and consent process.

I’m less persuaded by that as a solution. For a start, from a distance, it looks politically unsaleable. Even if the locations of the regional Feds reflects the politics and economics of 1913, rather than 2016, those institutions are “facts on the ground” and there would presumably be a great deal of resistance to removing that regional vote, and explicitly undermining the clout and status of the regional institutions. An alternative model, which he discusses, seems more plausible. Instead of subordinating regional Fed Presidents to the Board of Governors, why not instead make each regional Fed appointment a presidential appointment, with the full advice and consent process? It looks like a model that achieves much the same end – presidential appointment (and dismissability) and Senate scrutiny, without risking undermining the intellectual diversity that strong regional Feds have at times brought to the system. (I was struck a few years ago by the ability of a senior (regional) Fed researcher to publish a scholarly book that was quite critical of the Fed’s handling of monetary policy, including in quite recent years.)

Conti-Brown also proposes changes at the Board of Governors. He rightly highlights that the legislation vests power in the Board of Governors itself, not in the Chair, and yet – to a greater or lesser extent – all modern chairs have been allowed to assume a disproportionate amount of power and influence. Conti-Brown cites one former senior staffer as saying he would never have wanted to be appointed to the Board, as he would have far power/influence there. Part of the issue arises because of the repeated reappointments of chairs. Conti-Brown proposes term limits for the chair (two five year terms, so that there is a serious scrutiny of appointees at least every 10 years), and changes to the Board appointment terms as well. Personally, I suspect the recent proposal by former senior Fed economist, and now Dartmouth professor, Andrew Levin, for a single non-renewable seven year term for all senior Fed officials (board, chair, regional Presidents) would be a better way to go.

Conti-Brown also argues that key staff at the Board of Governors also have a big influence on policy, and that consideration should be given to making them presidential appointments, so that their values, ideologies, experiences etc can be tested and scrutinized. He is particularly concerned about the role of Fed’s General Counsel, whose advice has mattered a lot in handling financial crisis and regulatory issues. Making such positions presidential appointments seems like a step too far. Of course, advisers should be expected to have some influence. But the formal powers in the system rest with the Board of Governors (and the FOMC), the people who chose whether or not (and to what extent) to accept the advice offered by even the most senior staff. Ensure strong public scrutiny of those people for sure. But not the next tier down.

As so often with American books on public policy issues, it is light on international comparisons. Appointment and dismissal procedures for central bankers (and financial regulatory bodies) differ widely. Then again, I’m not aware of any other advanced countries with a system even remotely like that of the United States. The structure looks out of step with what we expect in public policy agencies today, and parts of it appear to be unconstitutional.

I found the US issues and analysis fascinating. But that is partly because thinking about the systems used in other countries, especially key ones, can help one think about the model for New Zealand. We don’t have a written constitution, and we don’t have a federal system. But we do, I think, expect that delegated powers will be exercised by people appointed by people we elected. That is typically the case with the numerous Crown agents and entities. Board members and Board chairs are appointed by the relevant Minister, and key decision-making powers typically rest with the Boards themselves.

That isn’t the case with the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, which exercises a great deal more discretionary policy flexibility (in monetary policy, and in financial regulatory matters) than any other statutory agency I’m aware of in New Zealand. There are some plausible reasons for putting some of the Reserve Bank’s functions at a considerable arms-length from day-to-day ministerial intervention (one could think of the administration of prudential policy as it applies to individual institutions), but even if one accepted all those arguments, there still don’t look to be good grounds for our governance model.

In the United States, the United Kingdom or Australia, the Governor (or chair) of the central bank is appointed by the government of the day. In the US case, the Fed chair is subject to Senate advice and consent, but only a presidential nominee can be appointed. The Senate cannot substitute its own candidate. In both Australia and the UK, the respective central government has untrammeled ability to appoints its own candidate. In the euro-system, there is lots of horse-trading and haggling among heads of government and finance ministers, but Draghi was appointed by politicians, from a field identified by politicians and their advisers.

Contrast that with the New Zealand system. The Minister of Finance appoints the Governor, but he can only appoint a candidate nominated by the Bank’s Board. The Minister can reject a nomination (as the US Senate can) but at no point in the process can he or she impose their own candidate. Now, of course, the Board itself is appointed by the Minister, gradually. Board members are appointed for five year terms, and although there are provisions for the removal of Board members, removal can only be done for cause (oddly, one possible cause is obstructing the Governor, but there is nothing comparable about the Minister). A new government might easily take more than a whole three year term to be able to achieve a majority of its own appointees on the Board. And the Minister of Finance does not even get to determine which of the Board members serves as chair, typically a quite influential role in any Board.

This was a model that was set up when the conception of the role of the Reserve Bank was (a) quite narrow, and (b) highly technocratic. If the Minister could specify a PTA clearly enough, who was on the Board or who was Governor wouldn’t matter much at all. But as everyone now recognizes, PTAs can’t sensibly be written that clearly, and there is nothing comparable for the other functions that the Governor exercises considerable discretion over. The values, ideologies and experiences of whoever is appointed as Governor are likely to matter considerably – much more so in New Zealand, since a single individual exercises those powers, with few near-term checks and balances.

So, operating wholly behind closed doors, the members of the Bank’s Board get to determine the person who wields more power, and more discretionary power, than almost any person in New Zealand, at least in matters economic. The individuals on the Board are probably mostly good and quite capable people (I know several of the current Board moderately well). But whose values and interests, and what “ideologies” or implicit models, are they serving or reflecting (consciously or otherwise)? What accountability is there for the choices they make, which can have material implications for short-term economic performance and for the soundness and efficiency of the financial system? It seems like a model with all too little democratic legitimacy.

If we are going to stick with the single decision-maker model for the time being (it will, surely, in time be amended) at least we should move back to a more conventional system in which the Minister of Finance (or Governor-General acting on advice) makes the appointment. He can take advice from whomever he wants – Treasury, the Bank’s Board, lobby groups, his colleagues – but his nominee should have to go through proper select committee hearings before taking up the role. We don’t have a model of parliamentary ratification of appointees in New Zealand, but the British model in which appointees to the Bank of England policy committees face considerable scrutiny in select committee hearings seems to add some value to the process, even though the committee cannot formally stop an appointment going ahead. It might be harder to do well in New Zealand, since there is less of a hinterland of MPs not eagerly jockeying for the next promotion to the ministry, but it has to be better than what we have now. At very least, Opposition MPs on the relevant committee could question, scrutinize and challenge the person the government has appointed to the role of Governor. The current Governor might, for example, have been scrutinized on how he thought about the housing market and the role of policy.

If we going to keep the role of the Reserve Bank Board as being primarily about holding the Governor to account, direct ministerial appointment of the Governor also seems preferable. Under the current model, the Board is responsible for the person appointed as Governor. That gives them an interest in judging that person to have done the job well (if the Governor is judged to have failed in that regard, it is at least in part a reflection on the people who chose the Governor). Monitoring someone clearly appointed by the Minister could be another matter (although structures still create risks that the monitoring Board gets too close to the Governor).

Over the longer-term, I think we need to move to a system in which committees appointed the Minister of Finance (and subject to parliamentary scrutiny before taking up the role) make monetary policy decisions and whatever financial regulatory decisions should appropriately be delegated to the Reserve Bank.

In the meantime, there is the becoming-pressing issue of the expiry of Graeme Wheeler’s term next year. As I have noted previously, it expires right in the middle of the likely election campaign (almost three years exactly since the last election). All main Opposition parties are campaigning for a different approach to monetary policy (time will tell what that specifically means). How can it be appropriate for a Board appointed exclusively by the current government to be recommending an appointee as Governor (who will exercise huge discretionary powers over our economic fortunes and financial system), to a Minister whose government might be out of office by the time the new appointment takes effect. A new government might have a quite different emphasis and should, in my view, more easily be able to give effect to that.

I’m not sure what the right answer is, given the current legislation. I’ve previously, somewhat reluctantly, suggested that Graeme Wheeler, if willing, should be offered a one year extension to his term, allowing the longer-term appointment to be made under the new government (National or Labour led). However, his performance over the OCR leak issue (including , in effect, minimizing the serious misconduct of a major corporate) makes me wonder whether even for a short period that would be a prudent option. Appointing an acting Governor – probably one of the existing deputies – for perhaps six months, might a better option. There is statutory provision for it – it was what happened when Don Brash resigned.

The US model does look as though it needs reforming. But, perhaps even more pressingly, so does New Zealand’s. It is simply out of step with

- the range of functions and discretionary activities the Bank now undertakes

- overseas practice in central banking and financial supervisions

- governance of other independent Crown entities in New Zealand.

It puts too much power in the hands of one person, and that a person whose appointment is largely determined by unelected people, operating with little or no effective scrutiny.

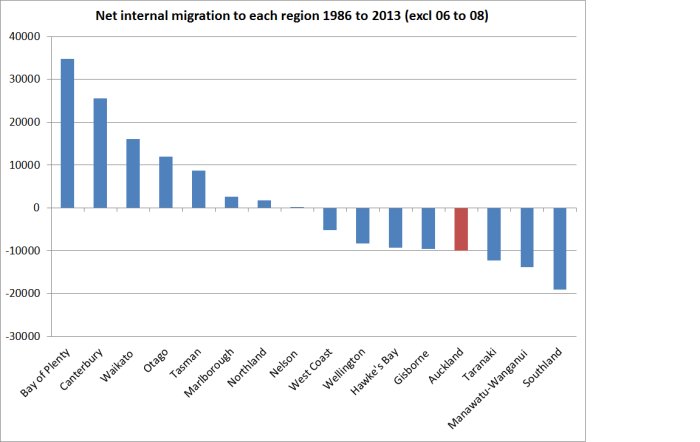

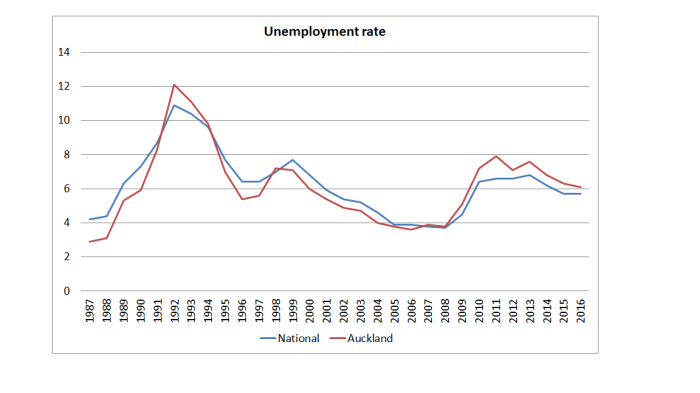

And it isn’t just that Christchurch has had a very low unemployment rate through the repair and rebuild period. Graphing the Auckland unemployment rate against that of the median region produces much the same picture.

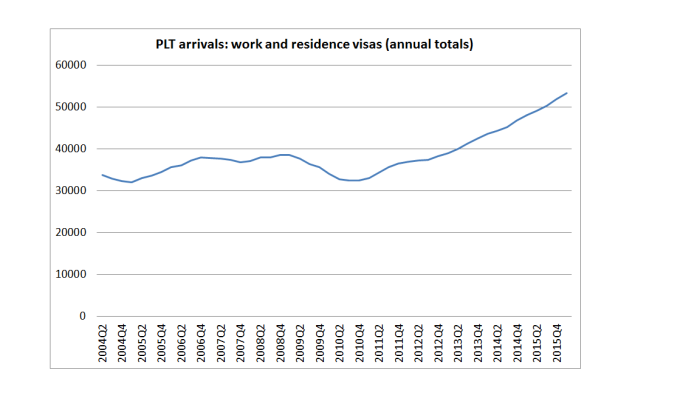

And it isn’t just that Christchurch has had a very low unemployment rate through the repair and rebuild period. Graphing the Auckland unemployment rate against that of the median region produces much the same picture. And the massive increase in student visa numbers (mostly to second tier non-university entities), many of whom later acquire residence, is on top of that.

And the massive increase in student visa numbers (mostly to second tier non-university entities), many of whom later acquire residence, is on top of that. Net, a small number of New Zealanders left Auckland for other parts of the country. Relative to Auckland’s population, the estimated outflow is tiny, but there is just no sign of New Zealanders flocking to the “success” of Auckland (and note that this period includes the outflow of people from Christchurch in couple of years after the earthquakes). Perhaps things have been different in the last three years, for which we don’t yet have data.

Net, a small number of New Zealanders left Auckland for other parts of the country. Relative to Auckland’s population, the estimated outflow is tiny, but there is just no sign of New Zealanders flocking to the “success” of Auckland (and note that this period includes the outflow of people from Christchurch in couple of years after the earthquakes). Perhaps things have been different in the last three years, for which we don’t yet have data.