No, that isn’t a statistic from South Korea or China. It is New Zealand in 1963.

My in-laws live in Waihi and whenever we are up there I point out to the children the old television factory, just off the main road, and give them a little reminder about the bad old days when New Zealand destroyed value by manufacturing and assembling television sets. Somehow I must have been under the impression that there was just one television manufacturing factory in New Zealand.

But browsing in a second-hand bookshop the other day, I stumbled on Electric Household Durable Goods: Economic Aspects of their Manufacture in New Zealand, an NZIER Research Paper published in 1965. There is 15o pages of analysis, statistics and discussion – not everyone’s cup of tea, but I found it fascinating.

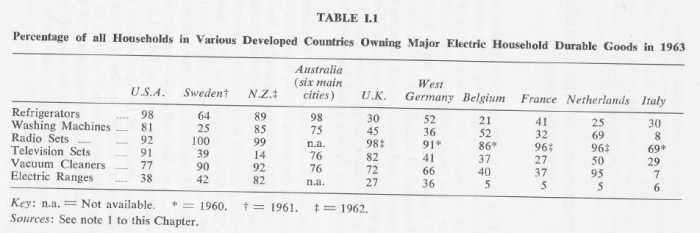

It doesn’t just have information on manufacturing. There is an interesting reminder of just how many more electrical appliances New Zealand households back then had than their counterparts in other advanced countries.

These sorts of international comparisons probably always have to be treated with some caution, but there is nothing very inconsistent with the data suggesting that at the time New Zealand still had among the highest real incomes per capita anywhere. Actually, I was a little surprised there were quite so many consumer electrical goods here, since New Zealand had high protective barriers which meant many such things cost more here than in other advanced countries. But, as the report notes, household electricity prices in New Zealand at the time were around half those in the United States and Australia, and around two-thirds of those in the United Kingdom. A government commission of inquiry had recently noted that in most areas the price of domestic electricity was below the cost of production and transmission.

The domestic manufacturing of electric household durable goods was largely a result of the very heavy regime of import protection and controls put on from 1938 and kept in place, with varying degrees of intensity, for decades afterwards (that Waihi factory didn’t close until the mid 1980s). As the NZIER piece notes

Before 1939, production of electric household durable goods in New Zealand, other than electric ranges and domestic radios, was practically non-existent.

Even for electric ranges, the report manages to cite statistics that over 80 per cent of those in use in 1939/40 had been imported.

The import controls which began in 1938 were precipitated by a foreign exchange crisis – which might well have led to a serious sovereign debt default if it had not been for the looming war – but also reflected an active desire by the government of the day to promote domestic manufacturing (for a variety of reasons, including pessimism about the prospects for (and volatility of) agriculture, a desire for greater self-sufficiency, and so on).

In some sense it worked. Many firms which had previously been importers and distributors turned to manufacturing. The NZIER paper quotes from the company history of Fisher & Paykel – a company established as importers and distributors.

The adoption by the Government in 1938 of a policy of controlling imports by licensing created an immediate problem for Fisher & Paykel Ltd,, as the company was trading principally in appliances imported from the USA. As dollar imports were even more restricted by the new system of import control than those from sterling sources, it became necessary to find alternative means of meeting a demand already barely filled and steadily increasing. The alternative was to produce the necessary appliances within the country, and so, in 1939, Fisher & Paykel entered the manufacturing field.

All sorts of New Zealand and foreign firms set up manufacturing operations here, producing all sort of products on a very small scale. It individually rational, and often highly profitable, but wildly inefficient. It took many decades to unwind.

But import licensing was considerably relaxed for a few years in the 1950s (although there were still typically tariff barriers), and there was a brief but substantial resurgence in imports of electrical household durables. During the brief period of liberalization, annual imports of washing machines (for example) were ten times what they had been in the periods of heavy controls before and after. Unsurprisingly, during that liberalization period there was some reduction in the number of domestic producers.

But when tight import controls were re-imposed in 1958, the whole focus on developing New Zealand industry was taken still further, with an emphasis on encouraging “manufacturing in depth”, and “since 1958 manufacturers in all industries have been encouraged to increase the ‘local content’ of their production”.

Television has been introduced into New Zealand since 1958 [experimental broadcasts only until 1960] and provides an excellent illustration of the policy in practice. Not only is the supply of receivers to the New Zealand market the sole prerogative of New Zealand manufacturers, but the manufacture of television tubes and other components in New Zealand has been deliberately encouraged……..where manufacturers are allocated a licence to use overseas exchange which is not tied to any particular product (the so-called “pool” licensing system), it pays to take advantage of the facilities of as local supplier even if some cost disadvantage is incurred.

And thus it was that in 1963 “the number of firms engaged in the manufacture of [TV] receivers (20) constituted a record for the production of any electronic consumer good in New Zealand”. The number of firms producing componentry is not listed. The New Zealand Official Yearbook records that in 1963/64 there were 35 firms engaged in “radio and television assembly and manufacture”, producing 113904 TVs and 93676 radios. The scale (or rather lack of it) is almost beyond belief – the average firms was producing just under 6000 units per annum.

Much of the focus of the NZIER is on the (in)efficiency of the New Zealand manufacturing operations. The author went to some length to get good data, including from foreign firms with manufacturing operations here and abroad. They cite one example of a European manufacturer of radios (a sector where, they noted, the economies of scale were less than those for the production of televisions) who supplied data on the estimated costs of production for different size production runs. That European manufacturer noted that they typically manufactured in Europe in production runs of 100000, but in New Zealand reasonably large firms typically did runs of around 5000 units. The cost of production per unit on that scale was around twice that for the European-sized production runs (scaling up to runs of one million units was estimated to produce further per unit cost savings of less than 10 per cent). Other estimates led the authors to conclude that New Zealand production was typically costing at least twice the “world” price.

The NZIER piece was primarily analytical and descriptive, rather than being policy-focused. But the author, rather drily, concludes:

If the cost of producing radio and television sets in New Zealand are likely to remain 100 per cent above costs of production in large industrial countries (and on the basis of the evidence presented in chapter VI this is a generous assessment of the higher costs of production in New Zealand) then it is a valid question as to whether the capital and labour now engaged in this industry could not be employed elsewhere to the greater national benefit.

Indeed.

Such staggeringly wasteful economic policies for so long.

(And since we have only continued to lose a little more ground relative to other countries since these particular policies were scrapped, one might hypothesise some ongoing policy problems. But that isn’t for today’s post.)

(And for anyone wanting a slightly caricatured sense of how things were, I recall this Alan Gibbs speech on New Zealand assembling television sets)