The belief that “diversity is good”, and probably “and more diversity is better” pervades our public debate. Sometimes people just mean intellectual diversity, sometimes diversity of managerial style, sometime gender diversity, sometimes ethnic diversity, sometimes diversity of nationalities. But too often is all lumped together in some amorphous mass. Who, after all, would argue that diversity might not always be good?

Enthusiasm for diversity pops up all over the place. The Secretary to the Treasury – often, it seems, something of a bellwether of elite sentiment – has celebrated diversity and called for more of it (but Eric Crampton has cast significant doubt on Makhlouf’s use of the literature on gender diversity).

Even amid the general elite celebration of “diversity”, I was a bit surprised to note a letter in last week’s Listener from a representative of top-tier law firm Russell McVeagh declaring that at that firm “we have made diversity our No. 1 priority in the past couple of years”. If I were a client, I’d probably have hoped that delivering top-notch legal advice had been the top priority. It may well have been, but it is telling that it sounded better to claim that diversity was their “No. 1 priority”.

Of course, a range of perspectives on many issues that face firms or public agencies or even individuals is likely to be helpful. For hard issues there is rarely only one useful way of looking at a problem, and all of us are prone to our own biases and blind spots. Then again, all cultures (national, organizational, local, or even family) rely on not too much diversity, and on shared assumptions (usually tacit) about how things are done, how differences are dealt with, debate encouraged (or suppressed), and about what sorts of behaviours are acceptable and which ones are not. And so on. It is simply how societies work, and that doesn’t change because a particular tide of liberal opinion wishes it were otherwise.

The alleged benefits of “diversity” are part of the case often made by the champions of our large-scale non-citizen immigration policy. Late last year, supported by taxpayer funding, lawyer Mai Chen published a 400 page Superdiversity Stocktake , championing the benefits of the diversity of ethnicities and nationalities that now make up modern New Zealand. She champions in particular the alleged economic benefits

Most of the benefits from superdiversity, such as greater innovation, productivity and investment, increase New Zealand’s financial capital, whereas most of its challenges adversely impact New Zealand’s social capital

Ian Harrison has done a nice piece reviewing how flimsy the economic case, and the evidence cited for it, in the Superdiversity Stocktake really is. But “diversity is good” seems to remain one of those mantras that business and political leaders repeat to each other.

Professor Bart Frijns of AUT (himself an immigrant) has been doing some interesting empirical work on one particular aspect of the impact of diversity. His co-authored paper is The Impact of Cultural Diversity in Corporate Boards on Firm Performance , and a couple of weeks ago I went along to hear him present it at a Victoria University seminar.

Frijn and his co-authors look specifically at the impact on the performance over 13 years (2002 to 2014) of 243 listed UK firms (excluding financial sector ones), making up 95 per cent of British stock market capitalization, of having directors who were not British citizens. Performance is here measured by the change in the market value of the firm (share price) relative to the book value (Tobin’s Q) and return on assets. The proportion of firms with at least one foreign director has been increasing, reaching 72 per cent by the end of the sample. Previous studies along these general lines have, so they report, produced mixed results, but those results included negative effects from the presence of foreign independent directors.

Here is the abstract to the paper

We examine the impact of cultural diversity in boards of directors on firm performance. We construct a measure of cultural diversity by calculating the average of cultural distances between each board member using Hofstede’s culture framework. Our findings indicate that cultural diversity in boards negatively affects firm performance measured with Tobin’s Q and ROA. These results hold after controlling for potential endogeneity using firm fixed effects and instrumental variables. The results are also robust to a wide range of board and firm characteristics, including various measures of ‘foreignness’ of the firm, and alternative culture frameworks and other measures of culture. The negative impact of cultural diversity on performance is mitigated by the complexity of the firm and the size of foreign sales and operations. In addition, we find that the negative effects of cultural diversity are concentrated among the independent directors. Finally, we find that not all aspects of cultural differences are equally important and that it is mainly the diversity in individualism and masculinity that affect the effectiveness of boards of directors.

As someone who hadn’t looked into this literature in any detail previously, those results surprised me. As a sceptic of the value of such “diversity”, I might have expected them to fail to find any statistically significant economic benefits (to the owners of the firms), but in fact they found statistically significant negative effects. Try as they might, they couldn’t consistently get rid of the negative effects. They test for all sorts of things. Does being based in a metropolitan area as opposed to a smaller town matter? Does the complexity of the business matter? Does it matter whether the foreign directors are independents or executive directors? Does it matter if the firm is also listed in the US? The negative effects aren’t there in every possible alternative specification – they disappear for executive directors, for very complex firms, and for those with large proportions of foreign sales for example – but there were no alternative specifications that generated statistically significant positive results.

The authors look at the nationalities of the foreign directors, using a (now quite old) cultural values framework developed by Hofstede for classifying each country. People from different countries (loosely “cultures”) differ on things like individualism, uncertainty avoidance, attitudes to the relationship between superiors and juniors (“power distance”), and “masculinity” (assertiveness, outspokenness, driven-ness, rather than gender per se). They also use some more recently developed “cultural scores” capturing dimensions like religion, language, or even genetic differences. As they note in the abstract above, not all cultural characteristics seem to matter much, but “individualism” and “masculinity” did in the results of this study.

Why might these effects exist? Boards need a variety of perspectives on the sorts of issues they face. But one element of a common culture is about trust, and cultural diversity seems to have the potential to undermine some of that trust (if one doesn’t understand quite how someone operates one is less likely to trust them, and perhaps less likely to take seriously their perspectives – even if you were part of appointing the person to the group). Thus cultural diversity looks as though it can be disruptive to group problem solving. There are benefits, but there are also costs, and – at least in this study – the costs generally seem to have outweighed the benefits.

However good this particular paper is, it is only one study. And, importantly, it is only one dimension of diversity, or even cultural diversity. In fact, it is only measuring nationality diversity – anyone who is a naturalized British citizen, no matter how recently, is British for the purposes of this study, even though their cultural similarity with most natural-born British directors might be considerably less than that of, say, an Australian citizen director who might have resided in the UK for thirty years. (As it happens, around half of all the foreign directors were from Anglo countries). And it doesn’t deal with cultural diversity within countries at all – the differences between a black and white South African director (in this period, only a decade after apartheid), and between most white and black British directors (given the socioeconomic disadvantages in the background of most of the latter) may be as important as those between “South Africans” and “British” directors.

Knowledge advances one paper – and one database – at a time. Other authors will be able to refine, or perhaps even refute, some of these results, and perhaps extend the analysis further. But it is the sort of paper that should be taken seriously by those enthusiastically championing the possibility (near- certainty many would have us believe) of diversity economic dividends here in New Zealand.

I was interested to see yesterday an article from the Financial Times economics columnist Martin Wolf on immigration and the Brexit debate. Wolf is a pretty reliably voice for elite informed UK opinion. He regards himself as a classical liberal, but seems to me pretty representative of a David Cameron/Tony Blair view of the world.

Economists tend to think it evident that immigration is beneficial to all parties. I am not convinced. High net immigration imposes significant negative externalities: greater congestion, more stress on social services, higher land prices and a need for significant investment in infrastructure and housing. If necessary investments are made, people suffer significant costs. If they are not, the costs will be higher still.

All this cannot be entirely ignored. Moreover, while I fully accept the arguments for the benefits of diversity, I understand why many differ, even feeling that they are “losing” their country. Some would argue that this idea of having inherited property rights in a country is illegitimate. I feel it is politically fundamental.

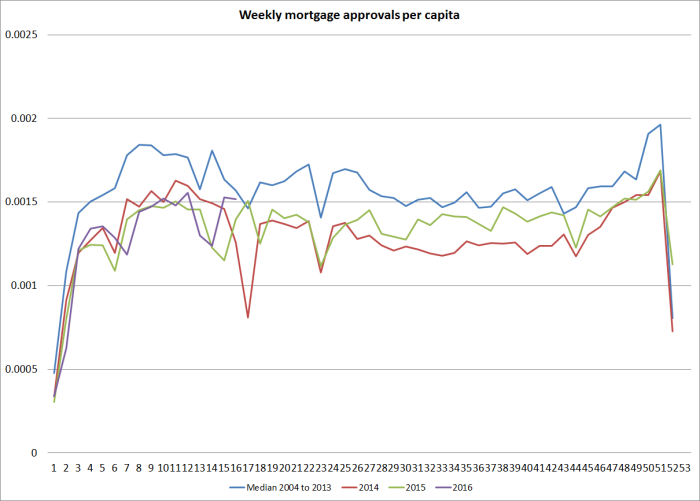

Quite a rebound in relative performance.

Quite a rebound in relative performance.