Bill Gross, the renowned US bond manager, puts out a monthly Investment Outlook opinion piece, a public outlet for some of his ideas and concerns. I used to read them quite regularly, and although I don’t do so these days, somewhere I saw a reference to the latest issue, and so dug it out.

His focus this month is on the advance of technology and the possible threat to the future employment opportunities of people in advanced countries. Among his possible solutions is a Universal Basic Income – as he notes (and despite the recent flurry of interest on the left in New Zealand) it has also had significant support on the right, especially in the US.

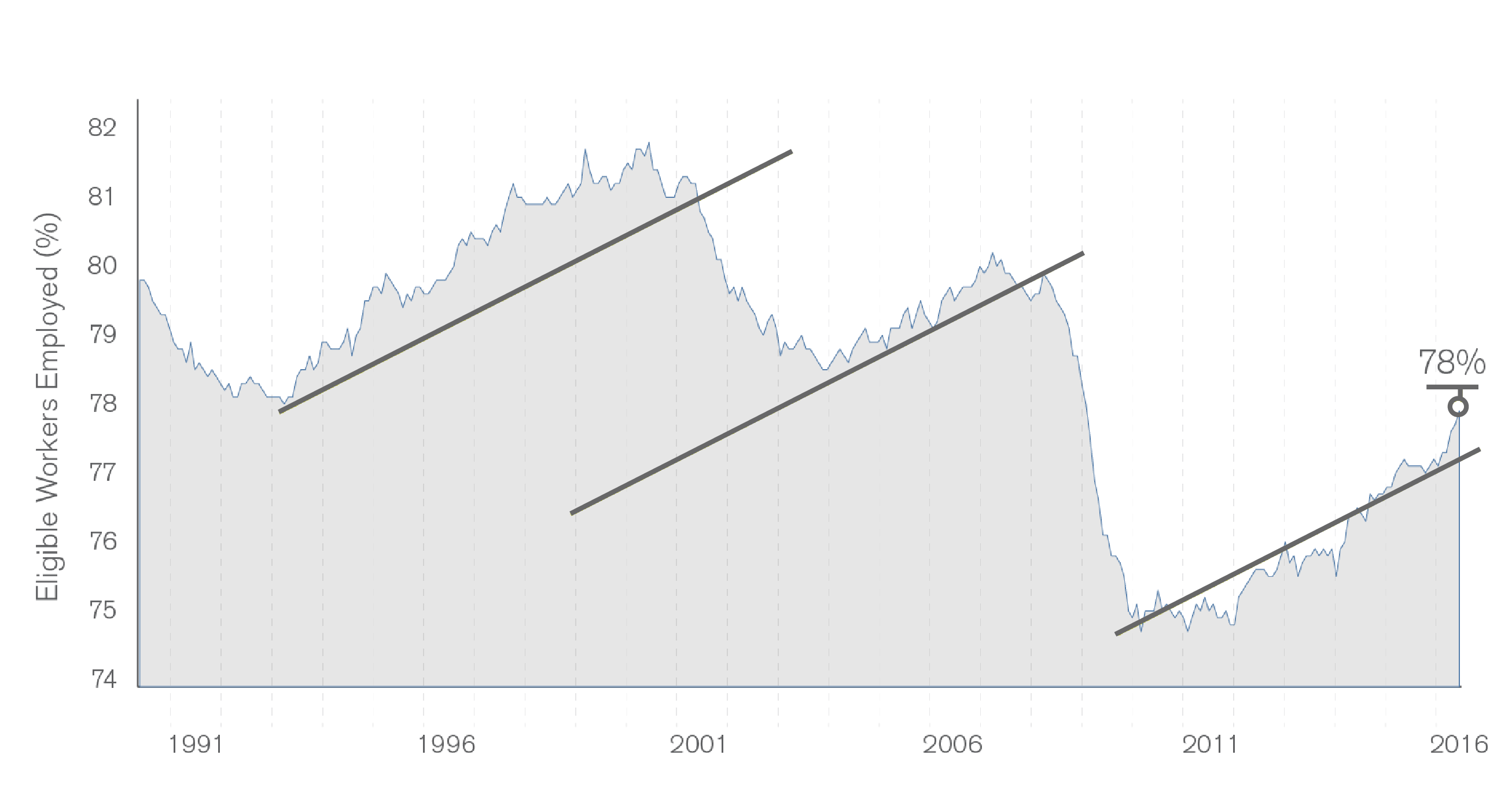

The centerpiece of his discussion is this chart

Chart I: Advance of the Robots, Retreat of Labor

As he describes it:

As visual proof of this structural change, look at Chart I showing U.S. employment/population ratios over the past several decades. See a trend there? 78% of the eligible workforce between 25 and 54 years old is now working as opposed to 82% at the peak in 2000. That seems small but it’s really huge. We’re talking 6 million fewer jobs. Do you think it’s because Millenials just like to live with their parents and play video games all day? I think not. Technology and robotization are changing the world for the better but those trends are not creating many quality jobs. Our new age economy – especially that of developed nations with aging demographics – is gradually putting more and more people out of work.

It is certainly a rather bleak picture, for the United States. But it isn’t remotely representative of the experience across the advanced world.

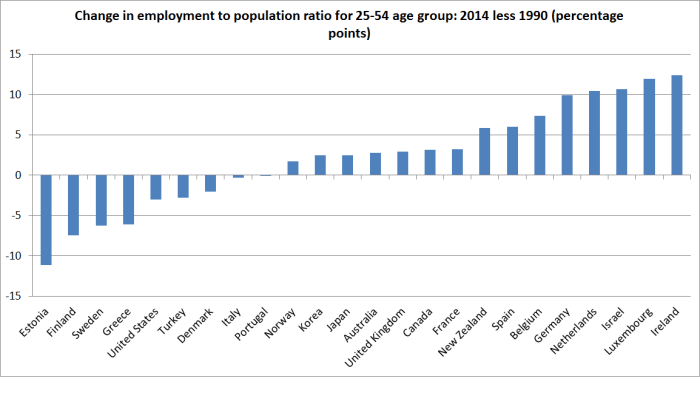

The OECD only has detailed annual labour market data to 2014. In the US, as Gross illustrates, the employment to population rate in 2014 for the 25 to 54 age group was 3.0 percentage points lower than it had been in 1990. A handful of countries had done even worse – Estonia, Finland, Greece and Sweden (three of them countries with little or no macro policy flexibility, now inside the euro). But the median OECD country (for which there was data right through the period) had employment to population rates 2.6 percentage points higher in 2014 – when most Western economies weren’t exactly buoyant – than in 1990. New Zealand did better than the median, being 5.8 percentage points higher than in 1990.

In fact, in eight of the 34 OECD countries, employment to population ratios for 25 to 54 year olds in 2014 were at the highest levels they had been in the last 25 years. On the other hand, 14 countries had employment to population ratios for this age group that were more than 3 percentage points below the 25 year peak. Perhaps unsurprisingly, 12 of them were euro-area countries, plus the United States and Sweden.

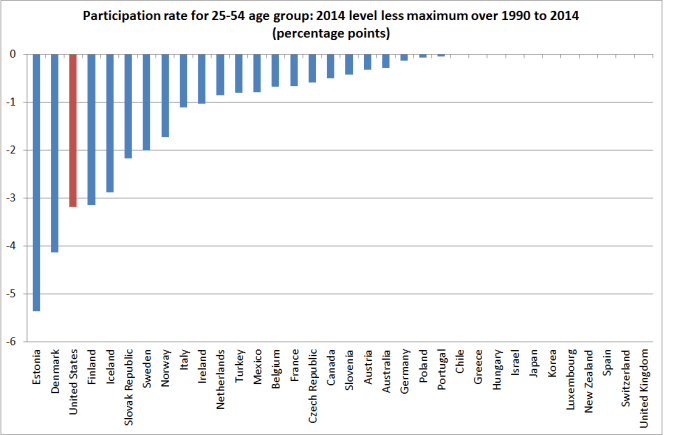

But employment to population ratios are quite substantially affected by the economic cycle. Participation rates – those employed and those actively seeking work – are less severely affected.

The participation rates for these prime-age people in 2014 were higher than they had been in 25 years for fully a third of the OECD countries (11 of 34, including New Zealand). And another 13 countries had participation rates in 2014 within 1 percentage point of the peak (participation rates are somewhat cyclical, and in few countries was 2014 a year of intense cyclical pressure on labour resources). The US was among a very small handful of countries where the participation rate was still well below the previous peak.

And here is how the US experience compares (and contrasts over the last 15 or more years) with that of the median OECD country, in a chart going back to 1980.

Looking at the participation rate, the contrast is even more striking and appears to have begun earlier.

Quite what is going on in the United States is an interesting question, but it looks to have been quite idiosyncratic.

Perhaps the answer lies in technological developments. In much of the economy, the US represented the technological frontier for several decades. But as an explanation it doesn’t really ring true when the US experience is contrasted with that of a bunch of similarly high-productivity (GDP per hour worked) northern European countries.

And perhaps there is a future to worry about in which there won’t be jobs for many of those who want them. But it does seem to have been a recurrent worry, going back at least as far as the Industrial Revolution, and – so far at least – the concern hasn’t come to anything very much for the economy as a whole. Productivity gains enable society to have more for the same, or fewer, inputs: labour once used to, say, connect telephone calls now does other stuff. In general, therefore, productivity gains are something to celebrate, and if anything the concern in the last decade or so has been how weak underlying productivity growth appears to have been.

Of course, at least when the public sector is concerned, genuine productivity gains resulting from the application of technology don’t always free up any labour anyway. My local community newspaper reports this week that the Wellington City Council libraries are introducing a new RFID self-service book-issuing system, which will “be quick and make using the library simpler”. What’s not to like about that? Cost savings should flow from that, I thought, which should be welcomed by the ratepayers. But no. Instead:

The council’s community facilities leader, councilor Sarah Free, said the upgrade would offer users the best of modern technology. … “I’m pleased to say there will be no staff reductions as a result of this upgrade”.

Perhaps there really is a revealed need for additional staff who will “focus on helping people find specialized resources or use library services”. It feels a bit like gold-plating to me – a council always keen to spend money, and rarely to save it – but in a sense in just illustrates the way in which the nature of jobs changes as technology advances without – as yet – any sign that it leaves large chunks of the population, who want to work, unable to find work.