What to make of the housing data released by the Labour Party, and of the subsequent debate?

I’m writing this partly to help clarify my own thoughts.

First, can the data be relied on? Well, no, but then no one really suggests that it can be. Even if we assume that the data Labour obtained are reported accurately, they are still only a partial snapshot, and report something that is likely to be aligned, but not that closely, with the subject of interest – purchases of residential property in Auckland by non-resident investors. It isn’t ideal, but then neither are other contributions to the debate (eg searches on juwai.com, or anecdotes from people on either side of the debate). There is a reasonable argument that there are no particular grounds for official statistics to be collected in this area. But if so then informal statistics and surveys are likely to be the best there is. And for those who do favour official data collections, well they are being put in place but the results won’t be available for months, since the data requirements don’t come into effect until 1 October.

Frankly, it seems reasonable to suppose that buying by non-resident Chinese is a material part of the market at present. If so, that is not a normal state of affairs. Generally, people do not buy individual residential properties in other countries as a part of a balanced investment portfolio. In particular, they do not buy such property in small cities at the end of the earth. People might, on occasion, own holiday houses abroad. The super-rich might have second houses in great world cities such as New York and London. But normal middle and upper middle class people in developed market economies don’t generally invest for their retirement in rental properties in faraway cities. Apart from anything else, monitoring costs are high. In fact, when people do own residential rental properties they are usually owned in locations quite close to where the owners themselves live.

In the 175 years since British government was established here, I expect this is the first time we’ve had this particular debate in New Zealand. And it is a different debate than one around immigration and housing. Reasonable people can differ about how much immigration we should have, and even where we might welcome migrants from, but if we are going to allow people to settle here they need to live somewhere.

“Capital flight” is a different issue. In Latin America, Africa, and now China, people who have acquired money in ill-governed countries – many of the gains themselves might be ill-gotten, but many won’t be – want safety and security for themselves and their families. That might be protection against a rickety domestic financial system. Or it might be protection against the current ruling elite cracking down on political enemies (as much of Xi Jinping’s recent “anti-corruption crackdown” seems to have been). It might just be protection against the risk of a substantial depreciation in the local exchange rate (which would probably be an appropriate course of action in China now, from a Chinese perspective). In countries where many forms of capital outflow are illegal, people have to take what routes they can.

So, I think people who talk of offshore-Chinese interest in residential property abroad as something we just have to get used to, or an inevitable feature of globalisation, are wrong. This demand is a function of the failure of China, not its success. There was never a time when British or American savers were managing their investments by buying houses in Sydney or Auckland. They were well-governed countries with rule of law protections. China, to date, is not.

People are also wrong if they suggest something odd in singling out Chinese purchasers. In most places around the world, the issue at present is about Chinese-sourced flows – and, of course, unlike many of corrupt countries from which capital has previously flown, China now has one of the largest economies in the world, so any spill-over effects potentially matter more. But if it were Russian or Argentinian buyers (which it isn’t, and has not ever been here), it would be just as much an issue.

Which is why I thought the intervention of the Race Relations Commissioner in this debate was particularly unhelpful and ill-judged.

But why might non-resident purchases of houses in Auckland matter? And to whom? I’d argue that they matter only because laws and administrative practices make new housing supply so sluggishly responsive to changes in demand. There is apparently substantial Chinese buying interest in Houston too, but when housing supply is much more responsive to changes in demand, foreign interest in local properties is largely beneficial to the local economy and its permanent residents. It is, in effect, just another export opportunity.

But things are different when supply is so sluggish – and when it is mostly government policy that makes it so. If supply were sluggish enough, even a few percentage points of additional demand could have material implications for house and urban land prices. I’d be surprised if anything like 20 per cent of demand in Auckland was from non-residents, but if the true number is five per cent (which wouldn’t surprise me) it could still be making a material difference to prices in the current rather over-heated environment. The Reserve Bank’s current and proposed lending restrictions are only likely to increase the relative importance of such offshore demand in explaining continuing price increases.

If most of any offshore-purchased houses are quickly put back on the rental market, offshore demand does not affect the availability of accommodation in Auckland. If anything, it would probably drive further declines in rental yields (though not in nominal rents). But it would still put home ownership further beyond the reach of New Zealand citizens and permanent residents living in our largest city.

The implications would be more serious if (and we don’t have the data) any material proportion of the offshore demand is being bought and left (largely) empty – perhaps occupied two weeks a year if the owners take a holiday here. Again, if housing supply were responsive, this demand would be pure gain (as at a holiday resort town), but in a city with tight housing supply restrictions (imposed, maintained and administered by central and local government), such demand would represent a reduction in effective accommodation supply, with consequences not just for the affordability of home ownership, but also for rents. In that case, there are gains from offshore demand for the immediate sellers of the property (at least if they are leaving Auckland) but the distributional consequences for the wider Auckland population look pretty awful. It doesn’t affect existing home owners, but the young and the poor typically end up worse off – and in Auckland, as David Parker has noted, those on the margins are disproportionately of Maori and Pacific backgrounds.

Bernard Hickey has suggested that offshore demand should be welcomed if it is accompanied by large scale apartment building, perhaps directly financed by Chinese capital. I’d have no objection at all to such investment, although as one who is a little sceptical of the estimates of the scale of any “shortage of physical houses”( the issue is mostly a land price issue), such a huge building programme could well sow the seeds of a subsequent collapse in Auckland property prices if the offshore demand for Auckland property proved not to be a long-term phenomenon. Real overbuilding tends to be more economically damaging than simply price overshoots.

In the longer-term I suspect (hope?) the offshore non-resident demand is a second or third order issue. Indeed, it may not be an issue at all. A more liberalised Chinese financial system would allow savers to diversify their holdings offshore through much more efficient investment vehicles. And Auckland is still a small city (and not exactly London, Sydney or San Francisco), compared to most of the others in which Chinese investors are reported to be interested, suggesting that demand would reallocate away from New Zealand if prices in Auckland got too high. In the medium to longer-term, it is still likely that the interaction between tight land use restrictions and high target rates of inward migration (which permanently boosts the population and demand for housing) will be more important for house and land prices in Auckland, and housing affordability. As I remain sceptical that housing supply can (politically) be substantially liberalised – I’m still curious to learn of any overseas examples where the controls have been substantially unwound – winding back the target level of inward migration needs to be discussed. It would be a more useful place to focus policy debate than overseas purchaser restrictions (and easier to implement effectively). Again, this is an issue that should be able to be debated without accusations of “xenophobia” or ‘racism” being flung around by the great and the good.

I favour a relatively unrestricted environment for foreign investment, putting foreign investors on the same footing as New Zealand citizens and residents (though not as more favourable footing, as ISDS provisions have the effect of doing). Most of our current restrictions appear unnecessary or counter-productive.

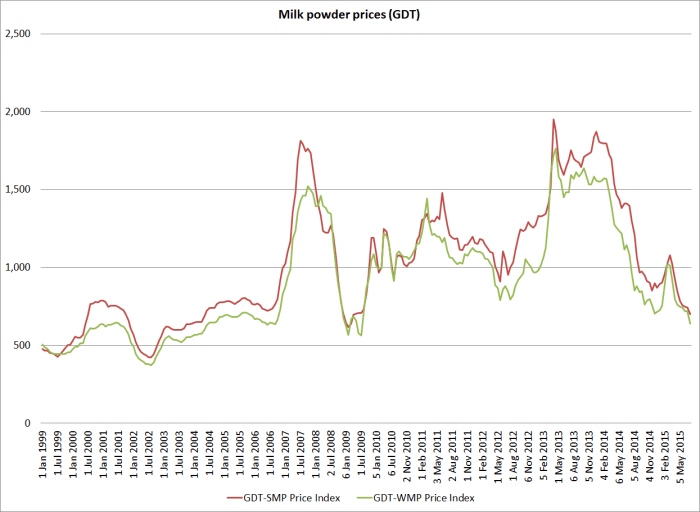

But when the government makes it hard to use urban land and increase housing supply, we are moving into a world of considering second or third best policy options if there is a large sustained source of offshore demand to own New Zealand houses. Policy should be made in the interests of New Zealand citizens and permanent residents, and it is not clear what interest of New Zealanders is served by allowing an unrestricted inflow of offshore demand (if indeed it is substantial). I heard David Mahon on Radio New Zealand this morning suggesting that even raising the issue would adversely affect our image in China, highlighting some deep “latent xenophobia”. Perhaps it will affect our image, but I rather doubt it will affect how much milk powder is sold, or the price at which it is sold. And when the country with the largest population in the world is both sufficiently ill-governed that many of its people just want to get their money out any way they can (after one of the biggest, and least disciplined credit booms in history), and just sufficiently liberal that there are some legal vehicles for those outflows, it is not inappropriate that other countries’ citizens might be wary about the implications. China – and the choices of the Chinese rich – matters for other countries in a way that Zaire mostly did not.

Are there easy answers? I doubt it. People talk of the Australian policy of allowing non-resident purchases only of new houses – which sounds not totally implausible in principle, but doesn’t appear to have worked that well in practice. If the government is confident that its registration scheme will produce robust data, perhaps an “offshore investor levy” – akin to Treasury’s dubious “Auckland investor levy” – could be considered. But I suspect any such provision would run into problems with provisions in any number of our free trade agreements. The same might go for banning non-resident purchasers altogether (eg from anyone without New Zealand citizenship or residence).

I’m not sure what the answer is, in a third best world. But in this debate, I reckon the medium-term interests of people needing accommodation in Auckland, and wanting to buy their own home, need to be the policy priority.

And good quality debate around what could be an important issue isn’t help by sloganeering from people on any side of the issue. I rather liked the guidelines for debate that Bryan Caplan and David Henderson have posted on Econlog in the last few days. I’d add just one other – to win a debate, and deserve to win it, one has to engage with the strongest arguments of those on the other side, not the weakest. Attacking straw men perhaps has its satisfactions, but doesn’t really advance understanding, or the cause of good policy.