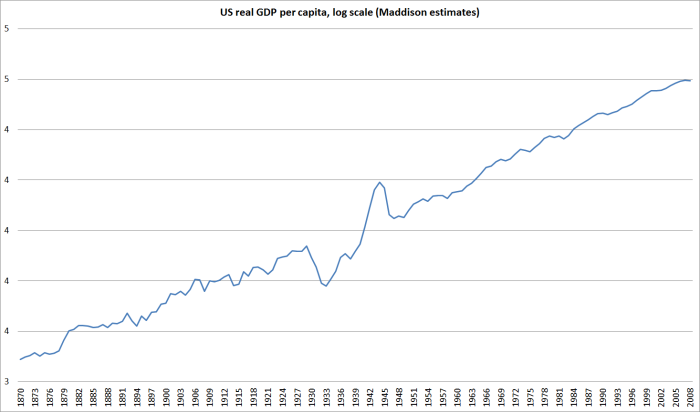

A couple of days ago I looked at how one might best classify countries, as to whether or not they had experienced a “financial crisis” since 2007. But this chart is one reason why I’ve become increasingly sceptical that “financial crises”, however one defines them, have large or enduring adverse real economic effects. I think I first saw it in a sets of slides by Nobel laureate Robert Lucas, and every so often I would use it to try to stir up a bit of debate at the Reserve Bank.

It is a quite simple chart of real per capita GDP for the United States, back as far as 1870. These are Angus Maddison’s estimates, the most widely used set of (estimated) historical data, and as Maddison died a few years ago they only come as far forward as 2008. The simple observation is that a linear trend drawn through this series captures almost all of what is going on. More than perhaps any other country for which there are reasonable estimates, the United States has managed pretty steady long-term average growth rates over almost 140 years. And yet, this was a country that experienced numerous financial crises in the first half the period. Lists differ a little, but a reasonable list for the US would show crises in 1873, 1884, 1893, 1896, 1901, 1907, perhaps 1914, and 1929-33. There were far more crises than any other advanced countries experienced.

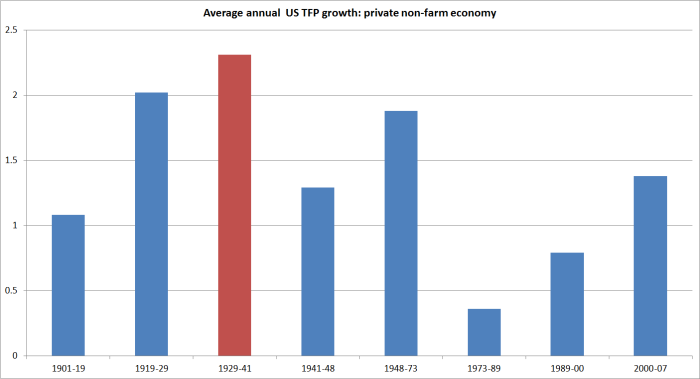

And yet, there is no sign that they permanently impaired growth, or income. One never knows the counterfactual, but right through this period the US kept on towards establishing the dominant position it was to hold in the decades after World War Two. Even the Great Depression, awful as it was (costly as it was to many people) does not look to have had permanent adverse effects. Another source I’ve bored people with over the past few years is Alexander Field’s excellent relatively recent book on US economic growth, productivity, and the Great Depression, A Great Leap Forward. Field reports the best estimates for TFP growth in the US over the last century, and growth was faster from 1929 to 1941 than in any of the other periods he presents. One might quibble about when to start and end these sub-periods, but 1929 was before the downturn became well-established, and 1941 is around when GDP per capita got back to pre-crisis trend (before temporarily going well above it in World War Two).

The United States in the Great Depression had almost all the factors that are often cited to explain why financial crises might have permanent or very long-lasting adverse effects:

- Lots of bank failures, and in a system without nationwide banks, disrupting the intermediation process.

- Lots of corporate failures

- Big changes in the price level (steep deflation)

- Huge regulatory uncertainty (including around the robustness of the judicial system – see, eg Roosevelt’s attempt to stack the Supreme Court)

- Significant fiscal costs (in this case, not bank bailouts, but the defaults by other Western countries on the huge US World War One loans).

And yet the underlying rate of innovation is estimated to have gone on just as strongly as before.

This is not, remotely, to trivialise the Great Depression. But it still looks a lot more like an event that became as severe as it was because of inadequate demand, and was resolved when sufficient strong aggregate demand returned (in the US case not until World War 2). Output lost in the interim is a real and substantial cost to the people involved, but the numbers get really big if something changes the long-term future path of growth. And there is no sign of that having happened in the many financial crises the US experienced from the 1870s to the 1930s.

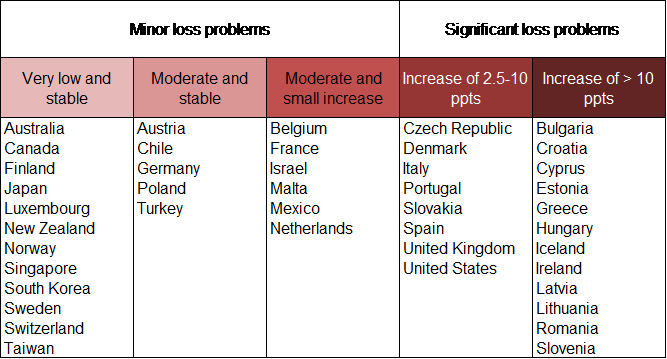

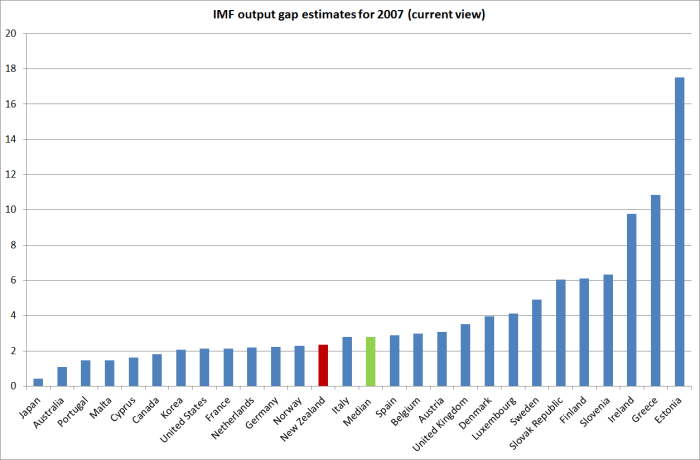

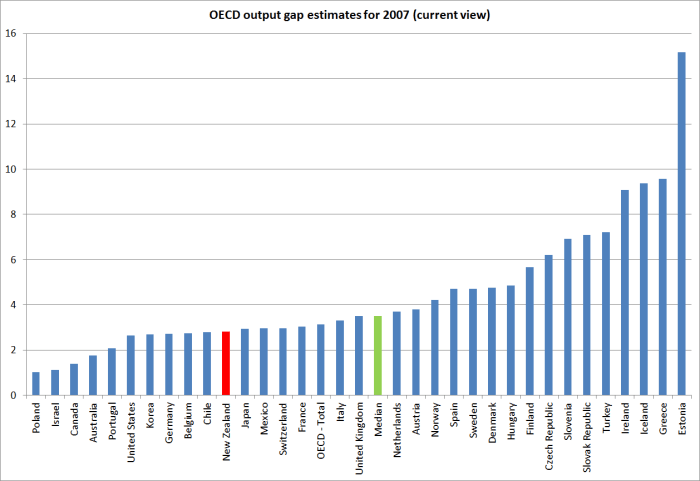

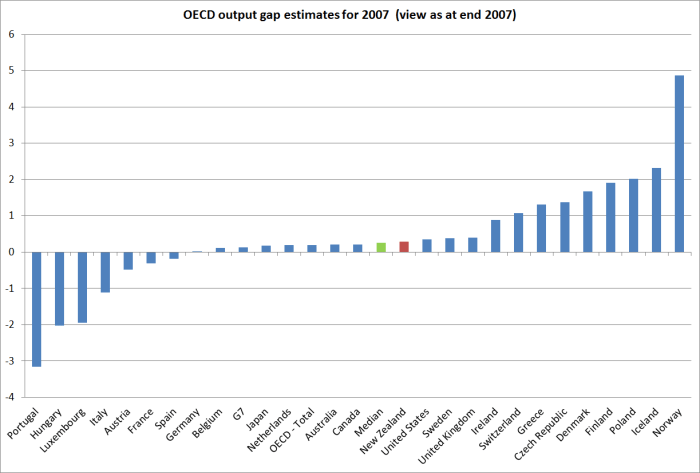

A few years ago, Andy Haldane of the Bank of England got a lot coverage for a speech in which he presented this table, suggesting that the cost of the 2008 financial crisis could be huge – 100 per cent or more of annual GDP.

If so, it could be argued that everything should be done, all resources of the state thrown at, avoiding such events, which – as Haldane put it – our children and probably our grandchildren might be paying for. But if there is little or no permanent reduction in the future path of per capita income, as a result of the financial crisis itself, the real economic costs of crises are much much smaller. And the benefits of any regulatory measures to reduce the risk of crises are commensurately smaller – all the more so when we allow for how little any of us know about the long-term costs and benefits of such regulatory restrictions. Even recessions occurring at the time of a financial crisis can’t all (or perhaps even mostly) automatically be ascribed to the crisis itself.

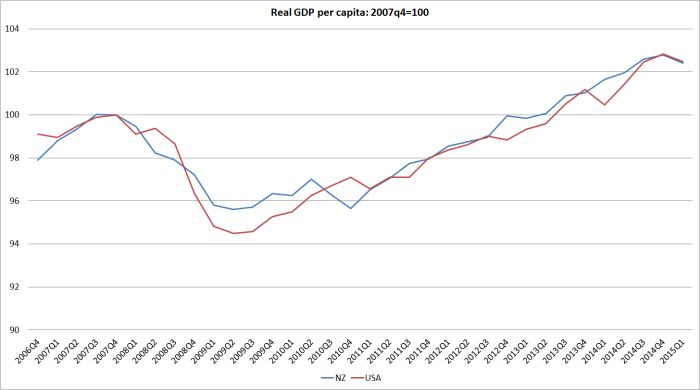

I’ll have a few more posts on related issues in the next few days or weeks. But recall where I started on this, and where I will loop back to. Per capita income GDP growth in New Zealand and the United States since 2008 has been very similar, even though New Zealand had only a minor domestic financial crisis, while the US was at the epicentre of a major global liquidity event, and many significant US institutions failed or came close to failing, and US lenders experienced very large losses. Sadly, as earlier posts have illustrated the relative productivity performance in New Zealand (relative to the US) has been even weaker.