A fairly prominent Australian politician was in town last week. Andrew Leigh was previously a professor of economics at ANU, and for the last eight years has been a Federal Labor MP. He is the Shadow Assistant Treasurer, Shadow Minister for Competition and Productivity (and spokesman on various other minor portfolios), and so presumably fairly likely to become a Federal government minister if the next election result follows the polls and Labor is elected.

Leigh was here to give a couple of lectures in the series being sponsored by the NGO Presbyterian Support Northern on topics related to child poverty and wellbeing. As it happens, next month I’m also giving one of the lectures in this series – on the role productivity growth plays in ending poverty – and if anyone is interested you can book one of the (free) sessions here (there is one in Auckland and one in Wellington).

I didn’t get to hear Andrew Leigh while he was here, but both his Auckland text and his Wellington text are available on line. The substance of both addresses is well worth reading – he is a widely-published researcher on inequality (the Auckland address) and has just published a book about the use of randomised control trials as a tool in better evaluating which policy interventions might work and which don’t (the focus of the Wellington address). I don’t claim to be a fan of the Australian Labor Party, but politics is likely to be better for having at least a few people, preferably on both sides of politics, able to address serious issues this seriously.

Having said that, I was mildly amused by the introduction to his Wellington speech. I guess it is standard advice to butter up, and flatter just a bit, your audience.

New Zealand has turned out to be a pretty good predictor of what’s likely to happen next in Australia.

New Zealand women won the right to vote nine years earlier than Australian women.

Your country enacted same sex marriage four years before we did.

You even gave Barnaby Joyce citizenship before we did.

So to be in New Zealand isn’t just a chance to see the sun rise a couple of hours earlier – it’s also an opportunity to get a sneak peak into some of the things that might shape Australia’s future.

And I have to say that as a member of the Labor opposition in Australia, I’m keenly hoping that this year or next will see Australia’s voters follow your lead in electing a progressive government.

I’m pretty sure that, even if it got a good laugh, he is wrong about Barnaby Joyce – a citizen by birth of both countries, and there was only a single birth.

But no mention at all – none, as far as I could see across two speeches – of the most striking area of New Zealand/Australia comparisons where Leigh must surely hope that New Zealand doesn’t offer a “sneak peak” into Australia’s future. And that is the, not trivial, matter of relative productivity and prosperity.

As I noted yesterday, for 100 years or so (from the time of our gold rushes onward) New Zealand and Australia are estimated to have had average real per capita incomes that were much the same. Each country had specific idiosyncratic events and influences, so that at times we did better, and then for a time they did better. Those differences were reflected in the trans-Tasman migration data – at times the (significant) net flow was one way, and at times the other way.

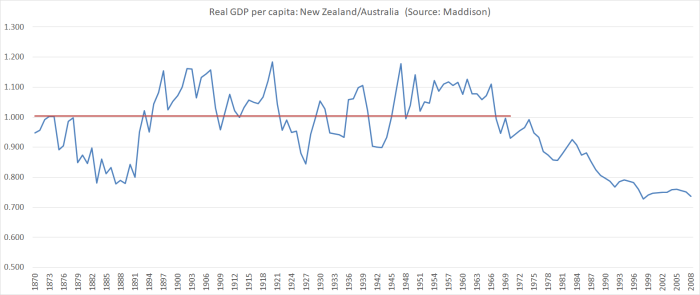

The standard collection of such data is that by former OECD researcher Angus Maddison Here is the chart of the data he judged best (no doubt far from ideal in both cases), starting from 1870 when he first reports annual numbers for New Zealand. (Maddison died a few years ago so the data aren’t updated to the present.)

The red line is the average of the series for the full period 1870 to 1970: on average, on these measures, New Zealand had very very slightly higher average incomes than Australia. On different measures you might get a slightly different picture, but the overall story won’t change much. The performance of our two economies was pretty similar. But it is no longer. The IMF’s current estimate is that New Zealand real GDP per capita, converted at purchasing power parity exchange rates, is about 76 per cent of that of Australia.

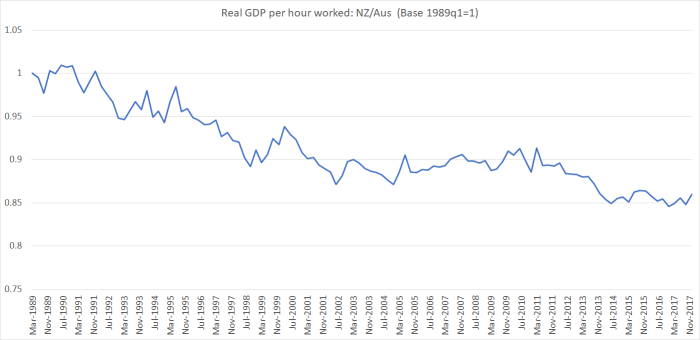

We don’t have a time series of productivity data for the historical period, and although Australia has an official series of real GDP per hour worked back to 1959, here official data can only take us back to the late 1980s. In this chart, I’ve shown the relative performance of labour productivity (real GDP per hour worked) in the two countries since 1989 (for New Zealand, using the average of production and expenditure GDP measures, and the average of the QES and HLFS hours series, as in earlier posts).

In 29 years, we’ve lost a lot more ground – 15 percentage points- relative to Australia. It isn’t a particularly steady process (at least as represented in these data) but the trend decline shows no sign of ending, let alone reversing.

And thus when, as in one of his speeches, Andrew Leigh notes that

It is not as though the child poverty rate is noticeably different in our two countries. According to the OECD, the child poverty rate – measured as the share of children living in households with disposable incomes of less than half the median – is 13 percent in Australia and 14 percent in New Zealand.

what he is omitting is that incomes in Australia are a lot higher, and thus so too is the relative poverty line measure he is using. Australia’s poor should be less badly off than our poor, because Australia’s relative economic performance is so much better.

For Australia’s sake, I hope New Zealand’s path doesn’t foreshadow their own. Then again, in some respects it already has. On the Maddison numbers, back in 1870 both New Zealand and Australia were more prosperous than the United States. As recently as 1938, we were about equal with the US. And now, we do particularly poorly, but Australia’s relative performance is nothing to write home about.

Interestingly, Leigh touches on one possible aspect of the story.

Third is to recognise the role that foreign investment plays in sustaining employment. As you know, the antipodes enjoyed among the highest wages in the world at the end of the nineteenth century. One reason for this was the high amount of land per person. While Europeans lived cheek-by-jowl, there was plenty of room to swing a sheep in Australia and New Zealand. In economic terms, one reason that wages were high was that the capital to labour ratio was high.

Today, both Australia and New Zealand have strong immigration programs. Migrants can fill skill gaps and start businesses, boost innovation and encourage exports. But they also have the inevitable impact of lowering the capital to labour ratio. To the extent that migrants are adding to the number of workers available to do a given job, this may put downward pressure on wages.

It was former Treasury Secretary Ken Henry who pointed out to me that foreign investment has the opposite effect. By increasing the available capital, it pushes up the capital to labour ratio. So by accepting foreign investment as well as migrants, a country can keep its capital to labour ratio constant, and therefore its wage rates.

I think that is partly true and partly not. As he notes, in the 19th century what marked out both countries was abundant land – which in turn attracted both migrants and foreign investment. These days, foreign direct investment can help improve prospects – and I’m strongly supportive of us being open to FDI – but FDI doesn’t add to the stock of land and natural resources (even if it can help exploit those resources more fully), and even when regulatory restrictions are out of the way, it flows in the direction of opportunity. Neither country has been particularly successful in seeing internationally competitive industries not based on our natural resources develop. Attractive opportunities in either location don’t seem thick on the ground,

It is, nonetheless, good to see a left-wing politician openly addressing these issues. Would that it were happening here.

Leigh’s other speech was devoted to the merits of randomised trials of proposed or actual policy interventions or welfare programmes. In many areas, they are the single best way of identifying what works and what doesn’t. Here are a couple of examples from his text (in this case, of programmes that proved not to work).

In some cases, the Education Endowment Foundation trialled programs that sounded promising, but failed to deliver. The Chatterbooks program was created for children who were falling behind in English. Hosted by libraries on a Saturday morning and led by trained reading instructors the program gave primary school students a chance to read and discuss a new children’s book. Chatterbooks is the kind of program that warms the cockles of your heart. Alas, a randomised trial found that it produced zero improvement in reading abilities.

Another Education Endowment Foundation trial tested the claim that learning music makes you smarter. Students were randomly assigned either to music or drama classes, and then tested for literacy and numeracy. The researchers found no difference between the two groups; suggesting either that learning music isn’t as good for your brain as we’d thought, or that drama lessons are equally beneficial.

In a similar vein, a recent randomised trial of free school breakfast programs in New Zealand schools found that it reduced hunger rates (by 8.6 units on the ‘Freddy satiety scale’, in case you’re curious). However, free breakfasts did not improve school attendance or academic achievement for low-income children.

Unfortunately, attractive as this approach is, it isn’t really an option for most of the sorts of policy interventions I write about here, which are economywide by construction. One can’t split the country into 100 different monetary regions, and apply different OCRs to each (chosen randomly) – and nor, frankly, should one want to. Even if some global dictator could do it across countries, there are far too few countries (and so many differences across them) for the results to be anything as valid as those from an evaluation of (say) a school music programme with (say) 500 kids split randomly into groups participating and not participating in the programme. The same goes for aggregate fiscal policies, or immigration policies. One might, perhaps, be able to do randomised trials around small aspects of, say, the Essential Skills visa programme, but not about overall approaches to immigration. I

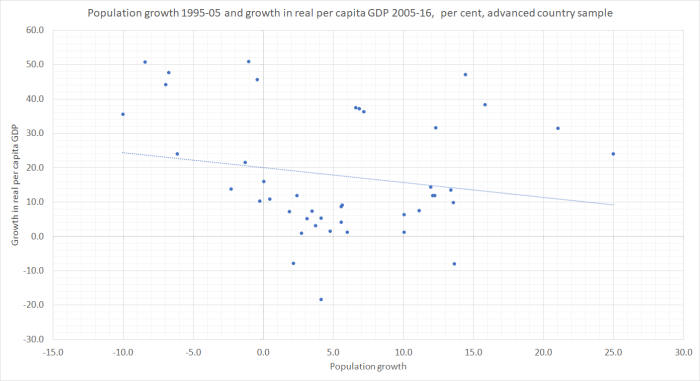

Instead, we are forced back onto looking what is really a small range of countries (say 40 advanced countries), over relatively short periods of history (the last couple of hundred years), and – given that and all the other individually confounding factors – it is perhaps less surprising that people of goodwill still differ on quite what role some of these policy interventions have to play, and what their overall effects are. Of course, many other areas of policy are much the same – think foreign affairs and defence – and the difficulty of reaching of conclusive results doesn’t change the importance of ongoing analysis, research and debate, testing and evaluating the relevant comparisons and insights that history (our own and others), theory, and current experience appear to be offering.

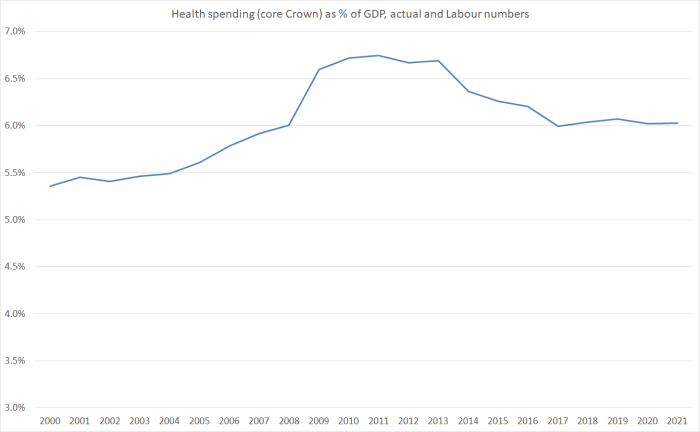

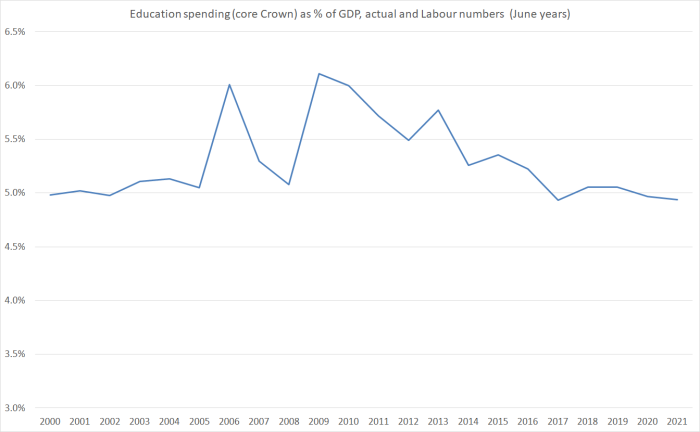

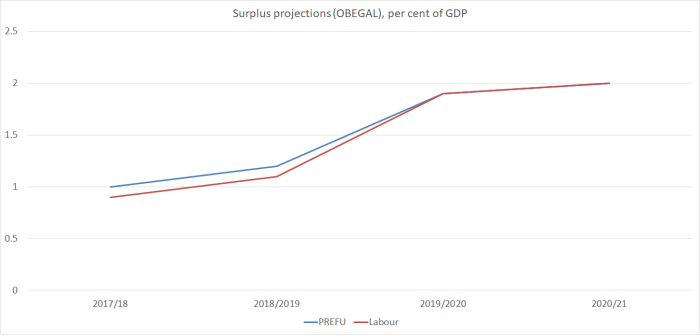

When net core Crown debt is already as low as 9.2 per cent of GDP – not on the measure Treasury, the government and Labour all prefer, but the simple straightforward metric – what is the economic case for material operating surpluses at all? With the output gap around zero and unemployment above the NAIRU, it is not as if the economy is overheating (the other usual case for running surpluses). Even just a balanced budget would slowly further lower the debt to GDP ratios. One could mount quite a reasonable argument for somewhat lower taxes (if you were a party of the right) or somewhat higher targeted spending (if you were a party of the left, campaigning on structural underfunding of various key government spending areas).

When net core Crown debt is already as low as 9.2 per cent of GDP – not on the measure Treasury, the government and Labour all prefer, but the simple straightforward metric – what is the economic case for material operating surpluses at all? With the output gap around zero and unemployment above the NAIRU, it is not as if the economy is overheating (the other usual case for running surpluses). Even just a balanced budget would slowly further lower the debt to GDP ratios. One could mount quite a reasonable argument for somewhat lower taxes (if you were a party of the right) or somewhat higher targeted spending (if you were a party of the left, campaigning on structural underfunding of various key government spending areas).

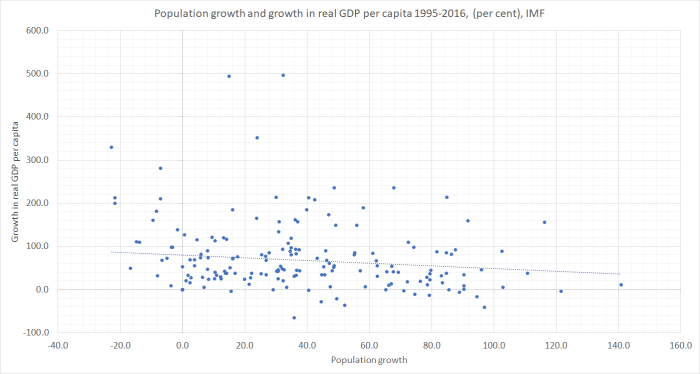

For those with sharp eyesight, New Zealand is a dot coloured orange.

For those with sharp eyesight, New Zealand is a dot coloured orange.