Two local articles on possible tax system/housing connections caught my eye this morning. One I had quite a lot of sympathy with (and I’ll come back to it), but the other not so much.

On Newsroom, Bernard Hickey has a piece lamenting what he describes in his headline as “Our economically cancerous addiction”. The phrase isn’t used in the body of the article, but there is this reference: “our national obsession with property investment”. Bernard argues that the tax treatment of housing “explains much of our [economic]underperformance as a country over the past quarter century”, linking the tax treatment of housing to such indicators (favourites of mine) as low rates of business investment and lagging productivity growth.

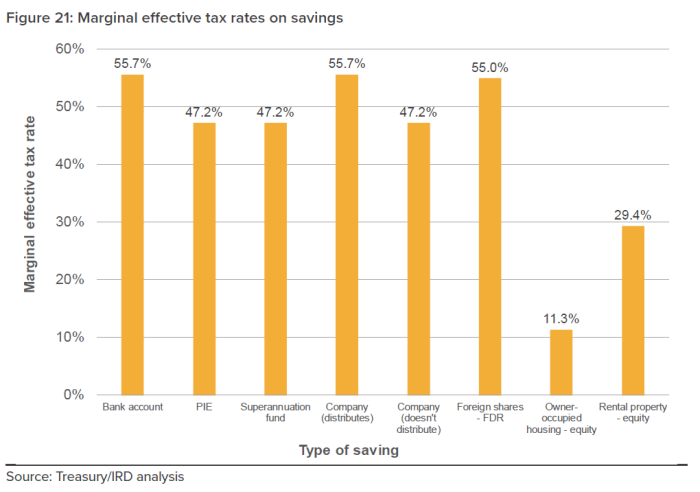

Centrepiece of his argument is this chart from the Tax Working Group’s (TWG) discussion document released last week.

Note that, although the label does not say so, this is an attempt to represent the tax rate on real (inflation-adjusted) returns.

It is a variant of one of Treasury’s favourite charts, that they’ve been reproducing in various places for at least a decade. The TWG themselves don’t seem to make a great deal of it – partly because, as they note, their terms of reference preclude them from looking at the tax-treatment of owner-occupied housing. They correctly note – although don’t use the words – the gross injustice of taxing the full value of interest income when a large chunk of interest earnings these days is just compensation for inflation, not a gain in purchasing power at all. And, importantly, the owner-occupied numbers relate only to the equity in houses, but most people get into the housing market by taking on a very large amount of debt. Since interest on debt to purchase an owner-occupied house isn’t tax-deductible – matching the fact that the implicit rental income from living in the house isn’t taxed – any ‘distortion’ at point of entering the market is much less than implied here.

Bear in mind too that very few countries tax owner-occupied housing as many economists would prefer. In some (notably the US) there is even provision to deduct interest on the mortgage for your owner-occupied house. You – or Bernard, or the TOP Party – might dislike that treatment, but it is pretty widespread (and thus likely to reflect some embedded wisdom). And, as a reminder, owner-occupation rates have been dropping quite substantially over the last few decades – quite likely a bit further when the latest census results come out. Perhaps a different tax system would lead more old people – with lots of equity in a larger house – to downsize and relocate, but it isn’t really clear why that would be a socially desirable outcome, when maintaining ties to, and involvement in, a local community is often something people value, and which is good for their physical and mental health.

So, let’s set the owner-occupied bit of the chart aside. It is simply implausible that the tax treatment of owner-occupied houses – being broadly similar to that elsewhere – explains anything much about our economic underperformance. And, as Bernard notes, it isn’t even as if, in any identifiable sense, we’ve devoted too many real resources to housebuilding (given the population growth).

So what about the tax treatment of rental properties? Across the whole country, and across time, any distortion arises largely from the failure to inflation-index the tax system. Even in a well-functioning land market, the median property is likely to maintain its real value over time (ie rising at around CPI inflation). In principle, that gain shouldn’t be taxed – but it is certainly unjust, and inefficient, to tax the equivalent component of the interest return on a term deposit. Interest is deductible on rental property mortgages, but (because of inflation) too much is deductible – ideally only the real interest rate component should be. On the other hand, in one of the previous government’s ad hoc policy changes, depreciation is not deductible any longer, even though buildings (though not the land) do depreciate.

But, here’s the thing. In a tolerably well-functioning market, tax changes that benefit one sort of asset over others get capitalised into the price of assets pretty quickly. We saw that last year, for example, in the US stock market as corporate tax cuts loomed.

And the broad outline of the current tax treatment of rental properties isn’t exactly new. We’ve never had a full capital gains tax. We’ve never inflation-adjusted the amount of interest expense that can be deducted. And if anything the policy changes in the last couple of decades have probaby reduced the extent to which rental properties might have been tax-favoured:

- we’ve markedly reduced New Zealand’s average inflation rate,

- we tightened depreciation rules and then eliminated depreciation deductions altogether,

- the PIE regime – introduced a decade or so ago – had the effect of favouring institutional investments over individual investor held assets (as many rental properties are),

- the two year “brightline test” was introduced, a version of a capital gains tax (with no ability to offset losses),

- and that test is now being extend to five years.

If anything, tax policy changes have reduced the relative attractiveness of investment properties (and one could add the new discriminatory LVR controls as well, for debt-financed holders). All else equal, the price potential investors will have been willing to pay will have been reduced, relative to other bidders.

And yet, according to Bernard Hickey

It largely explains why we are such poor savers and have run current account deficits that built up our net foreign debt to over 55 percent of GDP. That constant drive to suck in funds from overseas to pump them into property values has helped make our currency structurally higher than it needed to be.

I don’t buy it (even if there are bits of the argument that might sound a bit similar to reasoning I use).

A capital gains tax is the thing aspired to in many circles, including the Labour Party. Bernard appears to support that push, noting in his article that we have (economically) fallen behind

other countries such as Australia, Britain and the United States (which all have capital gains taxes).

There might be a “fairness” argument for a capital gains tax, but there isn’t much of an efficiency one (changes in real asset prices will mostly reflect “news” – stuff that isn’t readily (if at all) forecastable). And there isn’t any obvious sign that the housing markets of Australia and Britain – or the coasts of the US – are working any better than New Zealand’s, despite the presence of a capital gains tax in each of those countries. If the housing market outcomes are very similar, despite differences in tax policies, and yet the housing channel is how this huge adverse effect on productivity etc is supposed to have arisen, it is almost logically impossible for our tax treatment of houses to explain to any material extent the differences in longer-term economic performance.

And, as a reminder, borrowing to buy a house – even at ridiculous levels of prices – does not add to the net indebtedness of the country (the NIIP figures). Each buyer (and borrower) is matched by a seller. The buyer might take on a new large mortgage, but the seller has to do something with the proceeds. They might pay down a mortgage, or they might have the proceeds put in a term deposit. House price inflation – and the things that give rise to it – only result in a larger negative NIIP position if there is an associated increase in domestic spending. The classic argument – which the Reserve Bank used to make much of – was about “wealth effects”: people feel wealthier as a result of higher house prices and spend more.

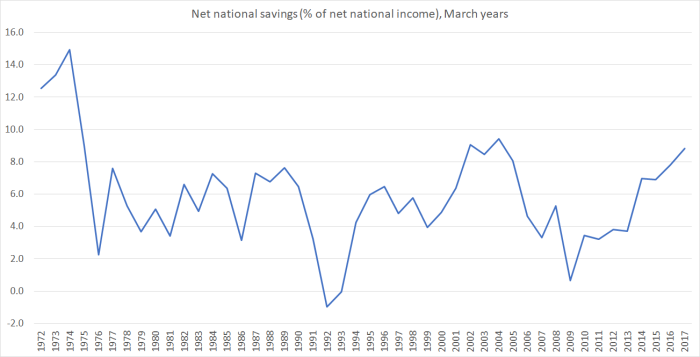

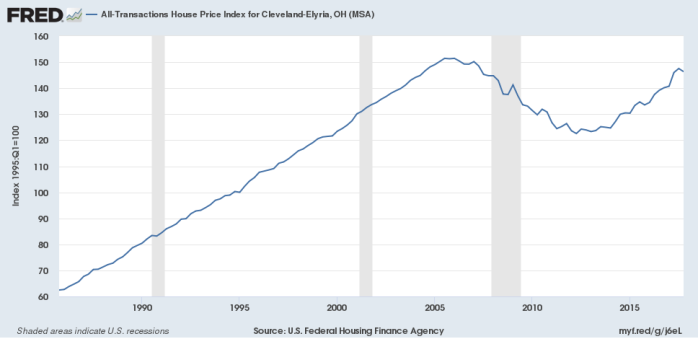

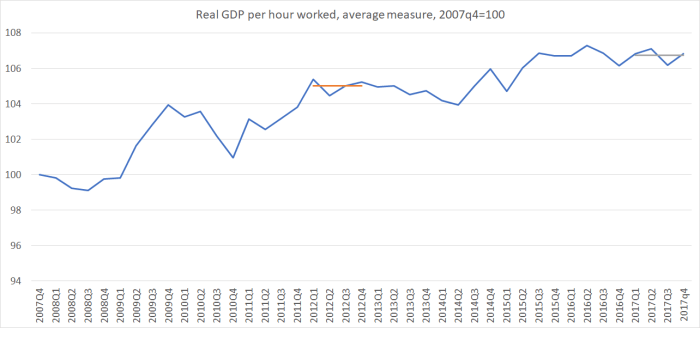

But here is a chart I’ve shown previously

National savings rates have been flat (and quite low by international standards) for decades. They’ve shown no consistent sign of decreasing as house/land prices rose and – for what its worth – have been a bit higher in the last few years, as house prices were moving towards record levels.

What I found really surprising about the Hickey article was the absence of any mention of land use regulation. If policymakers didn’t make land artificially scarce, it would be considerably cheaper (even if there are still some tax effects at the margin). And while there was a great deal of focus on tax policy, there was also nothing about immigration policy, which collides directly with the artificially scarce supply of land.

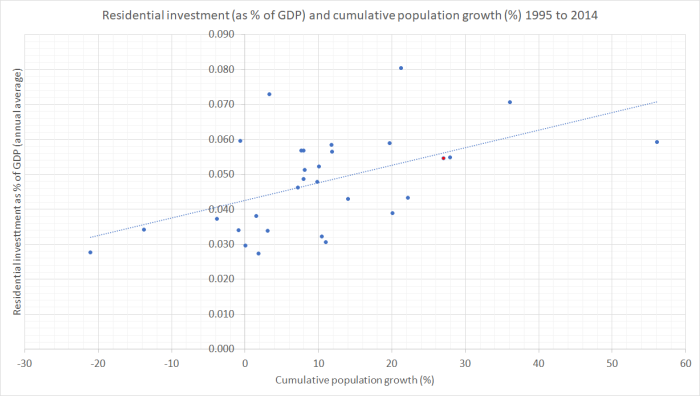

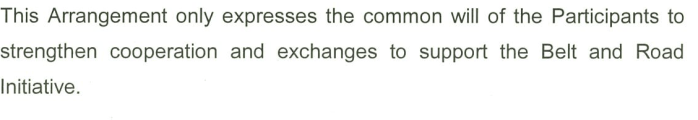

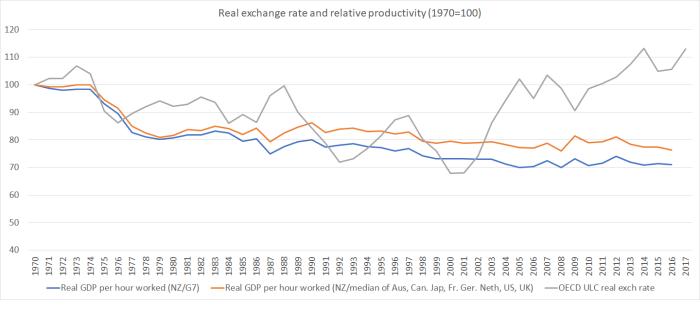

I’ve also shown this chart before

These are averages for each OECD country (one country per dot). New Zealand is the red-dot – very close to the line. In other words, over that 20 year period we built (or renovated/extended) about as much housing as a typical OECD country given our population growth. But, as I noted in the earlier post on this chart

The slope has the direction you’d expect – faster population growth has meant a larger share of current GDP devoted to housebuilding – and New Zealand’s experience, given our population growth, is about average. But note how relatively flat the slope is. On average, a country with zero population growth devoted about 4.2 per cent of GDP to housebuilding over this period, and one averaging 1.5 per cent population growth per annum would have devoted about 6 per cent GDP to housebuilding. But building a typical house costs a lot more than a year’s average GDP (for the 2.7 people in an average dwelling). In well-functioning house and urban land markets you’d expect a more steeply upward-sloping line – and less upward pressure on house/land prices.

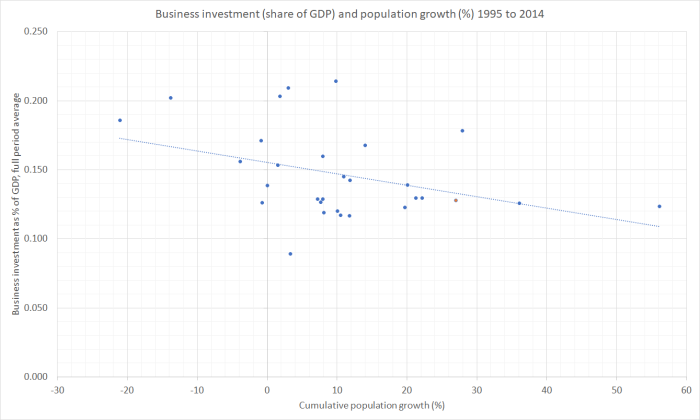

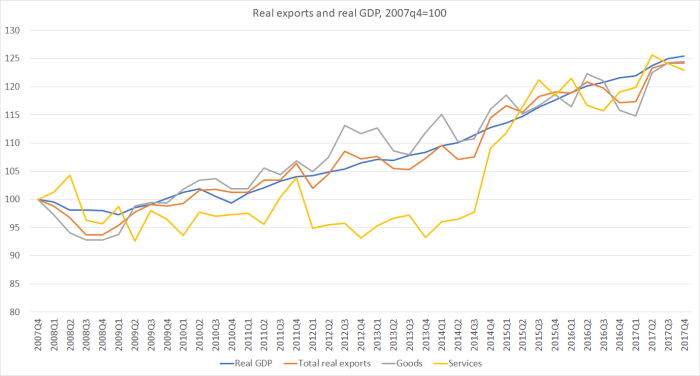

And, since Hickey is – rightly – focused on weak average rates of business investment here is another chart from the same earlier post.

Again, New Zealand is the red dot, close to the line. Over the last 20 years, rapid population growth – such as New Zealand has had – has been associated with lower business investment as a share of GDP. You’d hope, at bare minimum, for the opposite relationship, just to keep business capital per worker up with the increase in the number of workers.

This issue, on my telling, isn’t the price of houses – dreadful as that is – but the pressure the rapid policy-fuelled growth of the population has put on available real resources (not including bank credit). Resources used building or renovating houses can’t be used for other stuff.

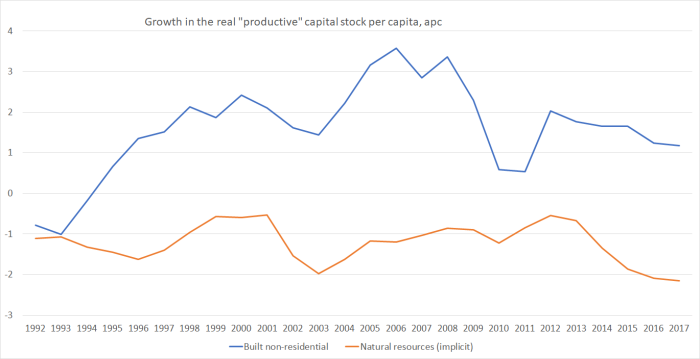

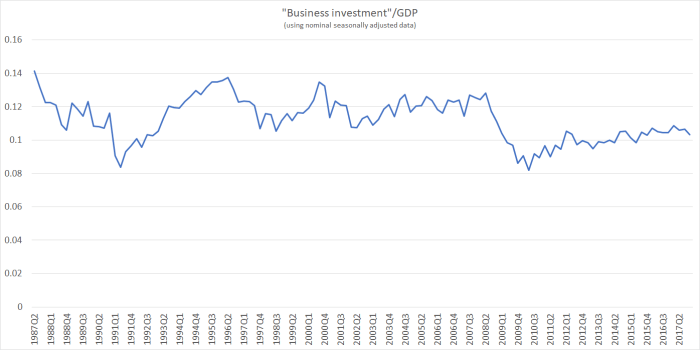

And one last chart on this theme.

The blue line shows the annual per capita growth rate in the real capital stock, excluding residential dwellings (it is annual data, so the last observation is for the year to March 2017), but as my post the other day illustrated even in the most recent national accounts data, business investment has been quite weak. I’ve added the orange line to account for land and other natural resources that aren’t included in the official SNZ capital stock numbers. We aren’t getting any more natural resources – land, sea, oil and gas or whatever – (although of course sometimes things are discovered that we didn’t know had been there). The orange line is just a proxy for real natural resources per capita – as the population grows there is less per capita every year, even if everything is renewable, as many of New Zealand’s natural resources are (and thus the line is simply the inverted population growth rate).

In New Zealand’s case at least, rapid population growth (largely policy driven over time) seems to have been – and still to be – undermining business investment and growth in (per capita) productive capacity. Land use regulation largely explains house and urban land price trends. And it seems unlikely that any differential features of New Zealand’s tax system explain much about either outcome.

The other new article that caught my eye this morning was one by Otago University (and Productivity Commission) economist, Andrew Coleman. He highlights, as he has in previous working papers, how unusual New Zealand’s tax treatment of retirement savings is, by OECD country standards. Contributions to pension funds are paid from after-tax income, earnings of the funds are taxed, and then withdrawals are tax-free. In many other countries, such assets are more often accumulated from pre-tax income, fund earnings are largely exempt from tax, and tax is levied at the point of withdrawal. The difference is huge, and bears very heavily on holding savings in a pension fund.

As Coleman notes, our system was once much more mainstream, until the reforms in the late 80s (the change at the time was motivated partly by a flawed broad-base low rate argument, and partly – as some involved will now acknowledge – by the attractions of an upfront revenue grab.

The case for our current practice is weak. There is a good economics argument for taxing primarily at the point of spending, and not for – in effect – double-taxing saved income (at point of earning, and again the interest earned by deferring spending). And I would favour a change to our tax treatment of savings (I’m less convinced of the case for singling out pension fund vehicles). I hope the TWG will pick up the issue.

That said, I’m not really persuaded that the change in the tax treatment of savings 30 years ago is a significant part of the overall house price story. The effect works in the right direction – and thus sensible first-best tax policy changes might have not-undesirable effects on house prices. But the bulk of the growth in real house (and land) prices – here and in other similar countries – still looks to be due to increasingly binding land use restrictions (exacerbated in many places by rapid population growth) rather than by the idiosyncracies of the tax system.

That seemed quite startlingly incompetent.

I had a further note from Mr Horne this noting that “unfortunately MBIE are still receiving enquiries around this. As mentioned the roles are around the teams involved in the labour market issues and are to fill existing vacancies not focused on a new initiative”. At his request I have elevated his earlier comment into the body of this post.

And, as far we can now tell, there is no new thinking going on about immigration and economic performance, and MBIE has still not published the (well overdue) annual data on approvals etc under current policy (when I asked the other day, I was told it should be out by the end of April, six months late on the normal schedule.