The Reserve Bank’s Survey of Expectations (of some reasonably “informed” respondents) came out the other day. It was one of the last significant pieces of New Zealand macro data likely to emerge before the Bank finalizes the forecasts for next month’s Monetary Policy Statement and the Governor makes his OCR decision.

As ever, there wasn’t that much media attention on these numbers, and arguably not much changed in this survey from the previous one. But in a sense that in itself should be newsworthy.

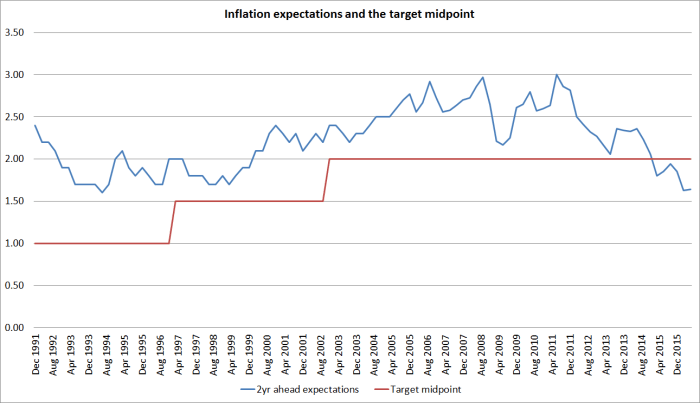

For a year now, the Reserve Bank has been reluctantly cutting the OCR, more or less reversing the ill-judged aggressive tightening phase the Governor undertook in 2014. I say only ‘more or less’, because although the current OCR is lower than the 2.5 per cent that prevailed for several years until the start of 2014, inflation expectations have also fallen. Using the two-year ahead survey measure, the real OCR was about zero at the start of 2014, but it is around 0.6 per cent now. And, as the Bank reminded us in the FSR last week, the margins banks face, over the OCR, in tapping wholesale funding markets have also increased.

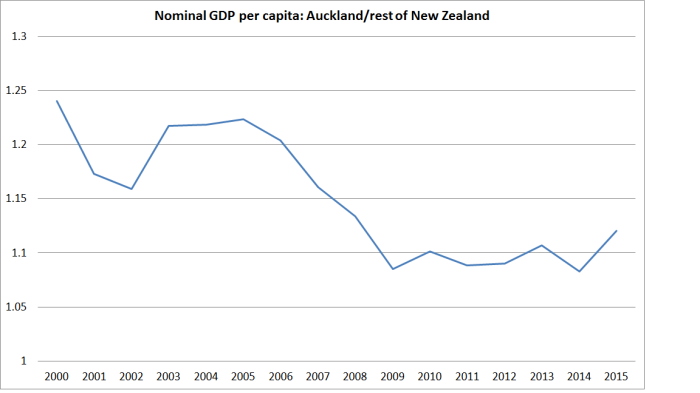

But the Bank has been cutting nominal rates for a year now, and still respondents to the survey don’t take very seriously the chances of the Bank getting inflation back to the 2 per cent midpoint of the target range, an explicit target that Governor himself had added to the PTA. The last year or so is the first time ever that two-year ahead expectations have been below the target midpoint. But despite 125 basis points of OCR cuts, there is no sign of medium-term expectations picking up again.

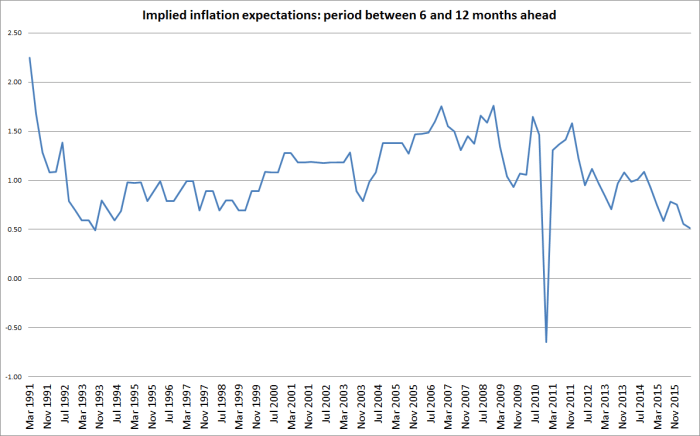

Some reporters noted that one year ahead inflation expectations had increased but (a) that shouldn’t have surprised anyone given the rise in world oil prices, and (b) there is no sign of the lift in expectations for the next couple of quarters flowing beyond that. The survey provides expectations for each of the next two quarters, and for the year ahead, which enables us to derive and implied expectation for the second six months of the year ahead (which shouldn’t be much influenced by eg changes in oil prices). Here is that chart.

I wouldn’t want to make much of a single observation, but the latest fall just continues a trend that has been underway ever since the 2008/09 recession. There is no sign of growing confidence that inflation will soon be getting back to target (note that the annualized rate of inflation for the second six months is only 1 per cent, at the very bottom end of the target range).

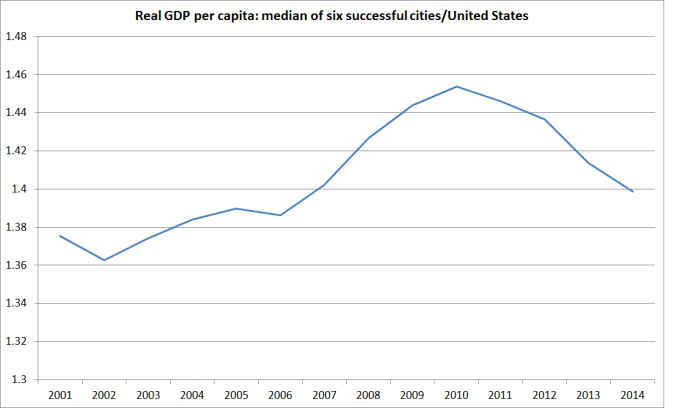

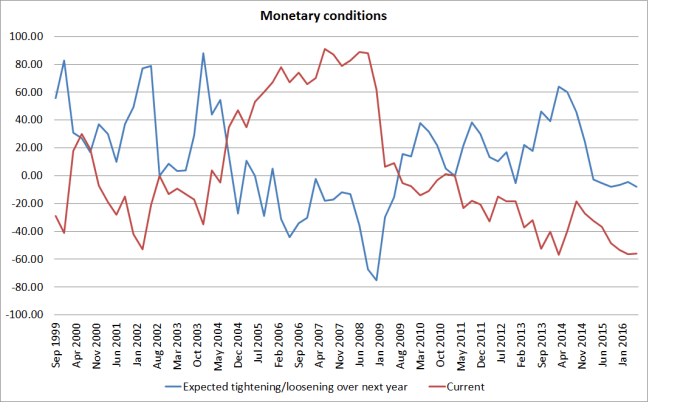

And these inflation expectations are based on expectations that monetary conditions will be eased further. In the history of this survey, respondents typically only expect monetary conditions to ease over the coming year when they are already judged to be quite tight.

For example, over the period from 2004 to 2008 respondents thought conditions were tight (the red line) and expected that they would ease over the year ahead (the blue line). At present, they think conditions are quite easy, but they still think conditions will (have to) ease further over the coming year. The size of the expected future easing isn’t large; it is the fact that they still expect further easings at all that is striking. Even with that expected easing, inflation expectations remain subdued.

If the Reserve Bank is keen to get these medium-term inflation expectations back up to around the target midpoint – as a marker of how much confidence people have in the seriousness with which the target is being pursued – there are broadly two ways to do that.

The first is through credibility/confidence effects. In other words, a substantial programme of interest rate cuts could, of itself, be enough to raise expectations of future inflation. People think along the lines of “gee, inflation has badly undershot the target, but I see the Bank is moving decisively now, and accordingly I’ll adjust my responses in the survey”. As already illustrated, there is no sign – a year into the easing cycle – of that sort of behavior at work.

If not, then they need to rely on the second channel: actually boosting economic activity, putting more pressure on scarce resources, and raising actual core inflation, leading people to revise up their forecasts of future medium-term inflation. This is probably usually the more important channel – people more often revise their forecasts/expectations in the light of actual experience with inflation.

The survey enables us to see whether respondents expect additional pressure on resources. Take the question about GDP growth, for example. In this survey expectations of GDP growth for the next one and two years actually fell. In the case of the two year ahead expectations, this fall reversed a rise in the previous quarter, but left expectations as low as they’ve been since the end of the 2008/09 recession. The survey doesn’t ask respondents for their population growth estimates, but at present the population is growing by almost 2 per cent annum, and if that continued then the expected 2.33 per cent GDP growth wouldn’t put much pressure on resources, or give much reason to expect inflation to rise. Perhaps respondents to the survey are just wrong, and will be surprised by how much growth actually happens. But at present there isn’t much evidence of a growth acceleration that might lift the core inflation rate.

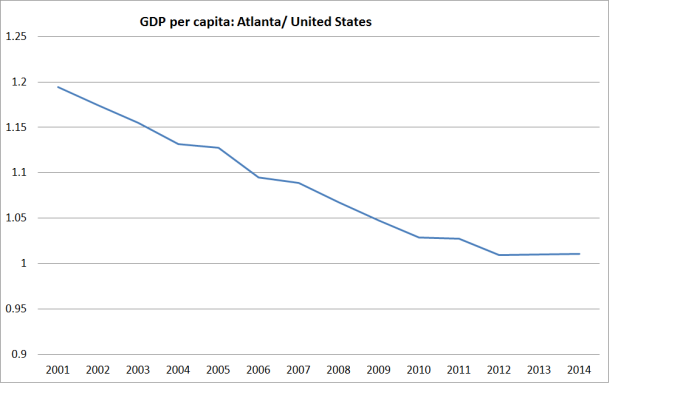

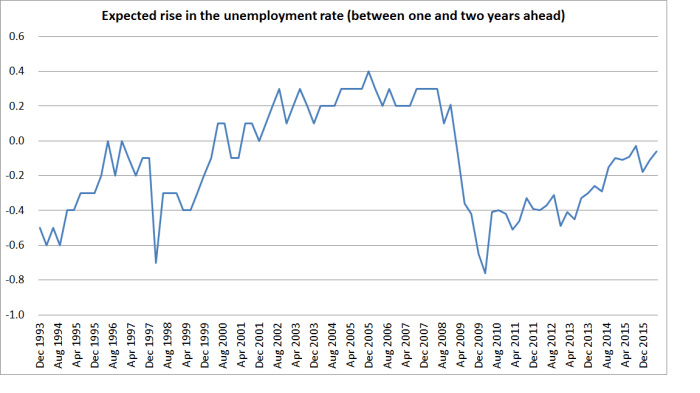

The survey also asks about unemployment rate expectations. Respondents are asked what they expect the unemployment rate to be in a year’s time and in two years’ time.

The chart shows the expected increase in the unemployment rate between one and two years ahead. When the unemployment rate is very low, and monetary conditions are tight (see chart above), as in the pre-recession period respondents typically expect that the unemployment rate will rise in future. After the 2008/09 recession, for several years respondents expected material falls in the unemployment rate. But now. with the actual unemployment rate at 5.7 per cent, they still expect it to be 5.53 per cent two years from now. There is simply no sign that these respondents expect capacity pressures to intensify from where they are. And, thus, they see no reason to expect underlying inflation (abstracting oil and tax changes etc) to head back to 2 per cent any time soon.

Who knows what the Reserve Bank will make of the recent data, including the Survey of Expectations. On their past track record, the expectations survey might provide them cover to not cut the OCR in June (“look, two year ahead expectations stabilized”). Given the Governor’s apparently strong bias to focus on the housing market whenever possible – for which he has no mandate – and avoid cutting unless the other data overwhelm him, it might make a plausible story for some.

But it would be the wrong message to take. The Governor’s mandate for monetary policy is to keep inflation near the 2 per cent target midpoint. Almost four years into his term, he has consistently failed to do that. Reasonable people might differ on quite how much responsibility he bears for that failure – what was forecastable and what wasn’t – but right now there is almost nothing suggesting (a) that informed observers have any confidence that inflation will settle at 2 per cent, or (b) that growth will accelerate and capacity pressures will intensify, in a way that might raise actual inflation and lead survey respondents to reassess the outlook for inflation itself. The succession of grudging OCR cuts over the last year has probably eased the disinflationary pressures a little, but the evidence suggests they have been nowhere near enough to address the problem of inflation persistently undershooting the target the Minister of Finance (on behalf of the public) has given the Governor.

If we look back over the last five years, there were various factors that have, and should have, supported demand/activity at any given interest rate. The terms of trade rose strongly on the back on high dairy prices, boosting domestic incomes. The Christchurch repair and rebuild process was a big boost to demand – didn’t boost productivity, but it sucked up real resources that couldn’t be used for other things. And at least on some readings, the world economy was providing some support to domestic activity – both the sluggish recovery in the West (about as sluggish as New Zealand’s) and the buoyant demand in many emerging economies.

None of those things is supporting any sort of intensified pressure on resources now. The terms of trade have fallen quite a lot, and while world dairy prices might be stabilizing (a) we can’t just assume that they will soon rise very much, and (b) the full effects on domestic spending etc of current weak payouts probably haven’t yet been seen. The Christchurch process has a long way to go, but there is no sign of the level of repair/rebuild activity rising from here (and the recent cement sales data actually showed a large fall in Canterbury sales). And there are very few bright spots in the world economy at present.

Perhaps the hope rests on a domestic (non-Canterbury) construction boom? Given the population pressures that might be welcome, but it remains much more of an aspiration than a forecast – respondents to the RB survey, expecting only very subdued GDP growth, seem to think so too.

Much better now for the Reserve Bank to move decisively to finally get on top of the downward drift in people’s expectation of future inflation, and the persistent undershooting of the target midpoint. At present, I reckon the Governor’s reaction function is one in which (changes in) house price inflation dominate, unless other data suggest to his forecasters a material risk of inflation staying below 1 per cent. That isn’t the target he has been given, but if that is something like the way he is operating, it is no wonder respondents to this survey see no reason to expect inflation to head back towards 2 per cent any time soon. The Governor has only 16 months left in office – just enough time, if he really took the issue seriously, to get underlying inflation settling back to around 2 per cent.