That was the subject of last night’s Law and Economics Association seminar. Eric Crampton (from the New Zealand Initiative) and I each spoke, and a good discussion followed. The LEANZ flyer captured the essence of our own different approaches

Our speakers have differing views on the subject:

According to Michael Reddell, for most of the last 70 years successive governments have promoted large scale inflows of non-New Zealand citizens. Through various channels, this helps explain why New Zealand has been the worst performing advanced country economy in the world over that time – before and after the 1980s economic reforms. Located on remote islands, in an age when personal connections are more important than ever, that performance is unlikely to improve much, whatever else we do, until the government gets out of the business of trying to drive up our population, against the revealed preferences and insights of New Zealanders. We can provide top-notch incomes here – as we did in the decades up to World War Two – but probably only for a modest number of people.

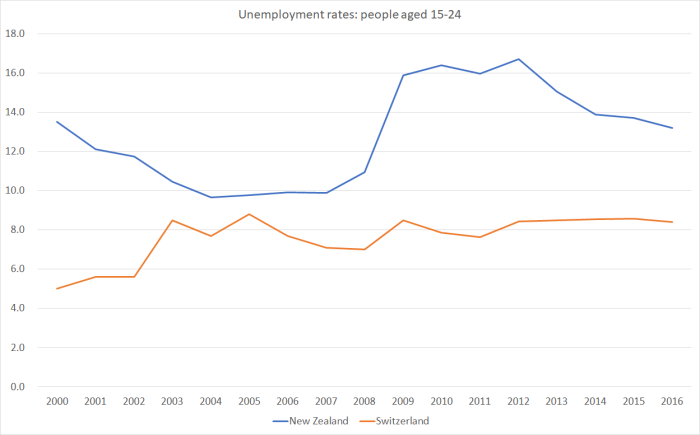

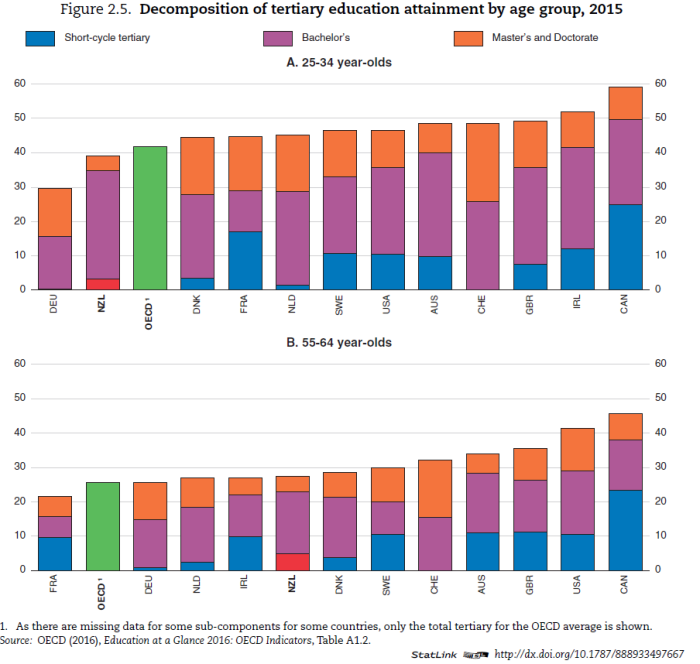

Eric Crampton on the other hand says: It’s easy to scapegoat immigrants for all of the world’s problems – and many do. Proving immigrants do any harm at all is substantially more difficult. The New Zealand Initiative’s 2017 report on immigration looked to the data on immigration and found it difficult to reconcile popular fears about immigration with the data. As best we are able to tell, immigrants have lower crime rates than native-born New Zealanders; the children of immigrants are more likely than Kiwis to pursue higher education; and, immigrants integrate remarkably well into New Zealand society. Arguments that immigrants are to blame for slow productivity growth in New Zealand are inconsistent with either the international evidence of the effects of immigration on wages, and with what New Zealand evidence exists. And where the benefits of agglomeration seem to be increasing, restricting immigration against the revealed preferences of migrants, of those selling or renting them houses, and of those employing them, is likely to do rather more harm than good.

Eric’s presentation (here) was largely based around the Initiative’s advocacy piece on immigration published earlier in the year, which I responded to in a series of posts (collected here). The text that I spoke from was under the title Distance still matters hugely: an economist’s case for much-reduced non-citizen immigration to New Zealand. We engage pretty amicably, and I’m still grateful for Eric’s post about this blog in its early days, in which he noted

Michael believes that too high[a rate] of immigration has been substantially detrimental for New Zealand, where I’m rather pro-immigration. But his is the anti-immigration case worth taking seriously.

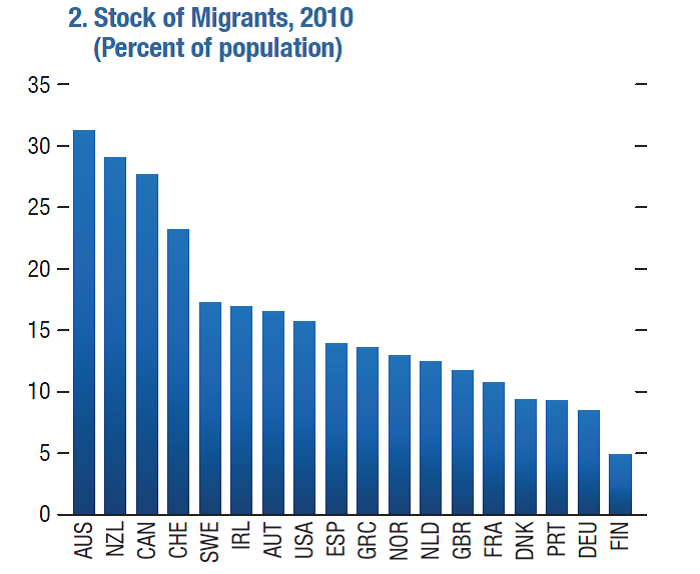

But in many respects, we were probably talking about different aspects of the issues. When he focused on New Zealand, the points Eric made mostly weren’t ones I disagreed with. We have been relatively successful in integrating large numbers of migrants, and migrants to New Zealand have been more skilled than those to most other advanced OECD countries. Migrants don’t commit crimes at higher rates than natives: if anything, given the prior screening, probably at lower rates. We both agree that housing supply and land use laws need fixing – although I’m more pessimistic than he is, because I’ve not been able to find a single example of a place that has successfully unwound such a regulatory morass. But much of his story seemed to be on the one hand an acknowledgement that there isn’t much specific New Zealand research on the economic impact of our immigration, and on the other an empassioned call for us therefore to simply follow the “international consensus” and international evidence on the issue, because he could see no reason why our situation would be different than that of other advanced countries.

By contrast, my presentation was really devoted to making the case – grounded in New Zealand’s economic history and experience – that New Zealand’s situation (and Australia’s for that matter) really is different than that of most advanced countries. Along the way, I suggested that the overseas evidence is less persuasive than it is often made out to be. After discussing the 19th century migration experiences, where the economic literature is pretty clear that migration contributed to “factor price equalisation” – lowering wage growth in the land-rich settlement countries, and raising it in the European countries the migrants left – I turned to the literature on the more recent experience.

There are two broad classes of empirical literature on the more-recent experience (in addition to the model-based papers in which the models in practice generate the results researchers calibrate them to produce):

- Studies of how wages behave in different places within a country depending on the differing migration experiences of those places, and

- Studies that attempt to estimate real GDP per capita (or productivity) effects from a multi-country sample.

There are lots of studies in the first category, and not many in the second. And almost all are bedevilled by problems including the difficulty of attempting to identify genuinely independent changes in immigration (if a region is booming and that attracts lots of migrants, higher wages may be associated with higher immigration without being caused by it, and vice versa).

I’ve never found the wage studies very useful for the sorts of overall economic performance questions I’m mainly interested in. Precisely because they are focused on different regions within a country, they take as given wider economic conditions in that country (including its interest rates and real exchange rates). They can’t shed any very direct light on what happens at the level of an entire country – the level at which immigration policy is typically set – at least if a country has its own interest rates. I’ve argued, in a New Zealand context, that repeated large migration inflows tend to drive up real interest rates and exchange rates, crowding out business investment especially that in tradables sectors. In the short-term, it is quite plausible that immigration will boost wages – the short-term demand effects (building etc) exceed the supply effects – but in the longer-term that same immigration may well hold back the overall rate of productivity growth for the country as a whole.

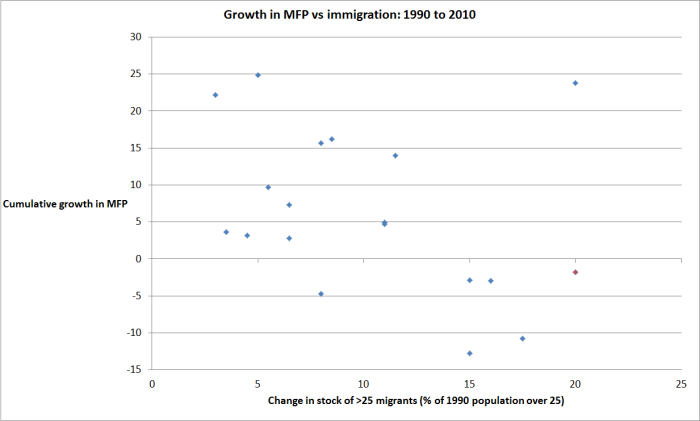

There really aren’t many cross-country empirical studies looking at the effects on real GDP per capita (let alone attempting to break out the effects on natives vs those on the immigrants themselves, or looking at superior measures such as NNI per capita). Those that exist tend to produce what look like large positive effects. So large in fact that they simply aren’t very plausible, at least if you come from a country that has actually experienced large scale migration. In one recent IMF paper, discussed in their flagship World Economic Outlook last year, an increase in the migrant share of the population of around 1 percentage point appeared to boost per capita GDP by around 2 percentage points. As I noted, if that were so it suggested that if 10 per cent of the French and British populations swapped countries – in which case the migrant share in each country would still be lower than those in NZ and Australia – both countries could expect a huge lift in per capita GDP (perhaps 20 per cent). Nordic countries could catch up with Norway in GDP per capita simply by swapping populations between, say, Denmark and Sweden.

And countries that were seeking to reverse decades of relative economic decline could reverse that performance by bringing in lots of migrants. Except, of course, that that more or less described New Zealand. Over the last 25 years we’ve had lots of policy-induced non-citizen immigration (and many of the migrants aren’t that lowly-skilled by international standards). And we’ve made no progress catching up with the other advanced countries; in fact we’ve gone on having some of the lowest productivity growth anywhere. As it happens, Israel – with more migrants again than we had – had similarly dismal productivity growth.

I could go on. For example, a country like Ireland certainly experienced a huge surge in productivity, but it was half a decade before the real surge in immigration started. And, the way the model is specified, the per capita GDP gains are sustained only if the migrant share of the population remains permanently high – if the migrant share dropped back so would the level of GDP per capita. None of it rings true. It speaks of models that, with the best will in the world, are simply mis-specified, and haven’t at all captured the role of exogenous policy choices around immigration.

But the thrust of my story was that New Zealand (and Australia) were different because their prosperity has, since first settlement, rested substantially on the ability of smart people, with good institutions, to make the most of fixed natural resources. And our prosperity still rests on those fixed natural resources – whereas that is no longer the case in most advanced economies – because it seems to still be very hard for many successful international businesses to develop and mature based in New Zealand (or Australia) when based on other than location-specific natural resources. Our services exports, for example, are still lower as a share of GDP than they were 15 years ago, and represent a small share of GDP by advanced country standards (even with subsidies to the film industry (direct) or the export education industry (indirect)).

Of course, really energetic and smart people – NZers and immigrants – will start businesses here that seek to tap global markets (often going straight to the world, not starting with the domestic market). But experience suggests that for all those talents and ideas, it is (a) harder to base and build such businesses here than in many other places, and (b) even among those that succeed, in time most will be even more valuable and more successful based somewhere nearer the markets, supplier, knowledge networks etc. Mostly, it looks as though remote places will successfully specialise in production of things that are location-specific. Gold or oil are where they are. They aren’t in London or San Francisco. Or Auckland. Much the same could no doubt be said for hydro power, or good dairy or sheep land.

Heavy reliance on fixed factors (land and associated resources) doesn’t doom a country to underperformance. But it does mean that if your country’s population is going to grow faster than that in other countries that are much less reliant on fixed natural resources, one needs a faster rate of underlying productivity growth just to keep up with the income growth in other countries. Either that, or new mineral discoveries (always there but not previously recognised). We’ve managed neither.

Against this backdrop, I concluded

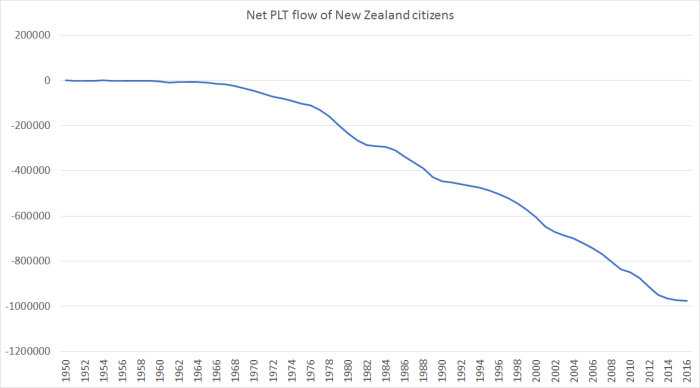

Specifically, now we need deep sustained cuts in our immigration programme. I’ve argued for 10000 to 15000 residence approvals a year. Doing that wouldn’t be terribly radical – we’d actually be putting ourselves more in the mainstream of international experience with immigration policy. Doing so would allow a rebalancing of our economy, and help us to meet pressing environmental challenges, in ways that would offer a credible promise of materially higher living standards for, say, 4.5 million New Zealanders. After 25 years – perhaps even 70 – when things have just gotten worse for New Zealanders relative to their peers in other advanced countries, it is past time to abandon the failed experiment – and radical experiment, not mainstream orthodoxy, it is – of large scale non-citizen immigration. A population growing as fast as ours is, driven up by government fiat when private choices are mostly running the other way (birth rates below replacements, net outflows of New Zealanders), in a location so remote, just doesn’t make a lot of sense.

In the discussion that followed, there was quite a lot of what seemed to me like wishful thinking, and a reluctance to accept the apparent limitations of our location. I can understand that reluctance. In the past I’ve been there myself – I’ve just this morning re-read the text I wrote some years ago for the 2025 Taskforce’s report on why distance was overstated as a constraint. I think Eric and I both accept that, if anything, personal connections are becoming ever more important (certainly than say 100 years ago, and perhaps even than 30 years ago). Perhaps one day, technology really will markedly ease those constraints – eg the possibilities that might arise from mooted six hour flights to San Francisco instead of twelve. As I responded to a questioner, if those ideas about the death of distance were being articulated in 1990, when New Zealand was just opening up, I’d probably have found them plausible. But we’ve seen no evidence of it being enough – no acceleration in (relative) productivity growth, no surge in city-based exports, really no nothing.

Eric also suggested that reliance on natural resources was a dangerous strategy, because of the potential over future decades for things like meat-substitutes to develop. They may well. And perhaps Ukraine (say) will get its act together, and a remote agricultural producer will be at even more of a disadvantage. I don’t have any expertise in those areas, but even if they are a possibility that we may have to face, so what? If the advantages/industries that have made New Zealand relatively prosperous were to go into further decline, it would be even more worrisome (for future living standards) if our policymakers had gone out on a limb and imported even more people. Because there is simply no evidence, despite all the hopes, and all the high-flown bureaucratic words, that an Auckland-based alternative economic future is coming to anything very promising. Auckland’s GDP per capita isn’t much above the New Zealand average – unlike the situation in places (think London or New York) where service-based international industries now predominate – and that margin has been shrinking further. When the economic opportunities in places go into relative decline people rationally leave those places. It is the way things work within countries. There is no particular reason for it to be any different between countries (see for example, the huge outflow of New Zealanders to Australia in the last 40 years or so).

I have sought to advance a narrative to explain as many as possible of the stylised facts of New Zealand’s underperformance, including

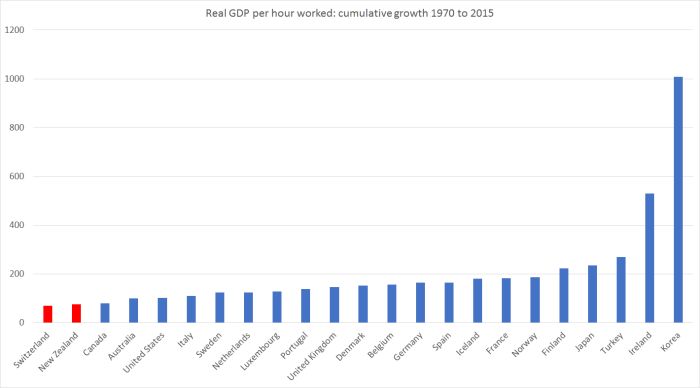

· There is still no sign of any labour productivity convergence (if anything, on average, real GDP per hour worked is falling slowly further behind),

· Total factor productivity is hard to measure, but on the measure there are we’ve kept on doing very badly there too,

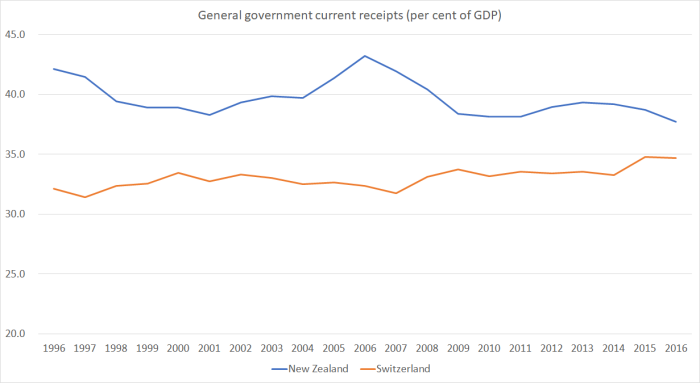

· We’ve had 25 years of the highest average real interest rates in the OECD (which could be a good thing if we had lots of productivity growth, but we haven’t)

· Not unrelatedly, even though our productivity has slipped behind over decades, our real exchange rate hasn’t adjusted downwards in the way that standard theory would teach,

· We’ve had weak business investment (bottom quartile of OECD countries, even though population growth has been in the top quartile), even though we started with low levels of capital, and

· We are still experiencing weak growth in exports (unlike most countries, we’ve seen no growth in exports/GDP for 25 years or more) and weak growth in the tradables sector of the economy (in per capita terms, no growth at all this century.

· Among those exports, there is little sign of any sustained move beyond reliance on natural resource based exports.

· Oh, and our one half-decent sized city, Auckland, has experienced declining GDP per capita, relative to the national average, over the 16 years for which we have the data.

Eric’s response last night was that there were many alternative narratives to explain our dismal long-term productivity performance. But, in fact, whether in their full report earlier in the year, or in discussion last night, the Initiative hasn’t really sought to outline a credible alternative story. In practice, any alternative seems to amount to “well, it would, or could well have been, worse without the large-scale immigration”. Perhaps it could have been. but surely it would be helpful to offer a story about the channels through which those worse outcomes could have come about, and how those channels are consistent with the indicators we’ve actually seen?

I ended the text I spoke from with an appendix setting out the key elements of how I’d change our immigration policy. Much of it will be more or less familiar to regular readers, but for the record here is the list.

Appendix

Some specifics of how I would overhaul New Zealand’s immigration policy:

- Cut the residence approvals planning range to an annual 10000 to 15000, perhaps phased in over two or three years

- Discontinue the various Pacific access categories that provide preferential access to residence approvals to people who would not otherwise qualify.

- Allow residence approvals for parents only where the New Zealand citizen children have purchased an insurance policy from a robust insurance company that will cover future superannuation, health and rest home costs.

- Amend the points system to:

- Remove the additional points offered for jobs outside Auckland

- Remove the additional points allowed for New Zealand academic qualifications

- Remove the existing rights of foreign students to work in New Zealand while studying here. An exception might be made for Masters or PhD students doing tutoring.

- Institute work visa provisions that are:

- Capped in length of time (a single maximum term of three years, with at least a year overseas before any return on a subsequent work visa).

- Subject to a fee, of perhaps $20000 per annum or 20 per cent of the employee’s annual income (whichever is greater).

I argue that this sort of approach would take more seriously the constraints of location, and offer much better prospects for lifting the productivity and living standards of something like the existing population of New Zealanders. Much of modern economics doesn’t pay much attention to fixed natural resources, and economics of location (at least in a cross-country sense). That is understandable – they aren’t the big issues for most other advanced countries (UK, USA, Belgium, Switzerland and so on). What is less readily pardonable is the willingness of our own political leaders, and supporting bureaucrats, to give so little attention to those factors and what they mean for our prospects. Firms, families, and societies all manage within constraints. Our governments do so when it comes to managing their own financial accounts. But otherwise, they seem free to just pretend that we are in a different situation than we are actually are, to persist with a modern Think Big that, decades on, still shows no sign of working out well for New Zealanders as a whole. Quite why New Zealanders allow ourselves to be carried along, when the evidence is against it, is something of a mystery.