Today I’m continuing on with the New Zealand Initiative’s chapter four, on the (claimed) economic benefits to New Zealanders of large scale non-citizen immigration. I don’t have the appetite to try to comment on every questionable claim in the report, so I start with a section headed “Agglomeration – Bigger is Better?” in which (despite the question mark) the Initiative appears to position itself firmly behind not just the proposition that immigration is good for us, but also the proposition that a bigger population is good for us.

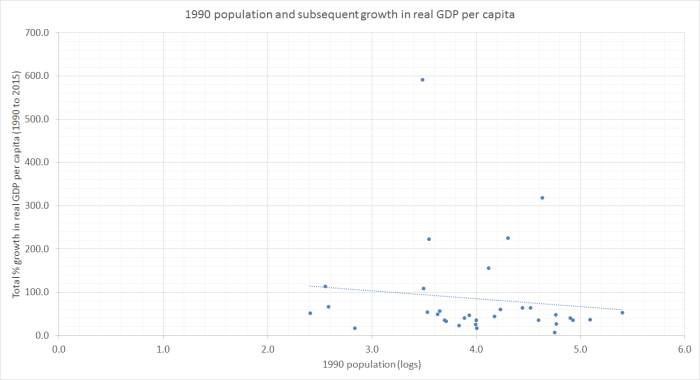

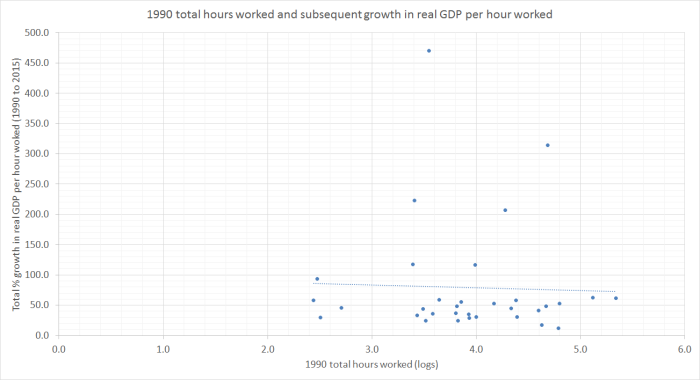

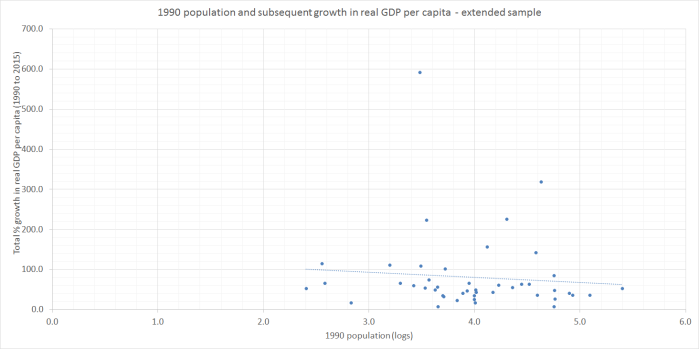

There is no good evidence I’m aware of for the latter proposition. At a more informal level, I illustrated in this post that large countries (by population) haven’t grown faster (per capita income or productivity) than small countries. And, of course, consistent with this impression, we have seen many more small countries emerge in the last few decades.

What there is little doubt about is that within countries people and economic activity tend to organise themselves in ways in which the higher productivity activities are increasingly more often found in larger cities. Cities exist in substantial part because it was found economically advantageous for them to do so. But it isn’t all that way, by any means. Natural resource based production tends to occur where the natural resources are – be it farming, oil and gas extraction, mining, or whatever. And the observation that within countries an increasing share of high value economic activity is undertaken in cities, tells us little or nothing useful about comparative national economic performance, given the successful co-existence of highly productive large and small countries.

The Initiative seems keen to take the other view

Places, cities in particular, with large, dense populations face lower transport costs in goods, people and ideas. It is cheaper to supply capital or consumer goods and find good workers; there is a better network for knowledge exchange across people. All vital components of economic growth. The existence of ‘agglomeration economies’ has been established in a number of studies. A meta-analysis of 34 studies found that the positive effects of spatial concentration on productivity remain even after controlling for reverse causality. Another meta-analysis highlights the importance of considering the various mechanisms through which agglomeration can produce benefits. New Zealand’s low economic productivity is partly explained by our small population, says Phillip McCann based on economic geography and urban economics.

But, as they acknowledge, I’ve pointed out what appears to be a pitfall in the argument in the New Zealand context, at least when it is used to back encouraging large numbers of new people into Auckland – what I’ve termed, the 21st century Think Big strategy.

Reddell contends that Auckland’s failure to produce significantly higher growth

compared to the rest of the country contradicts this explanation.

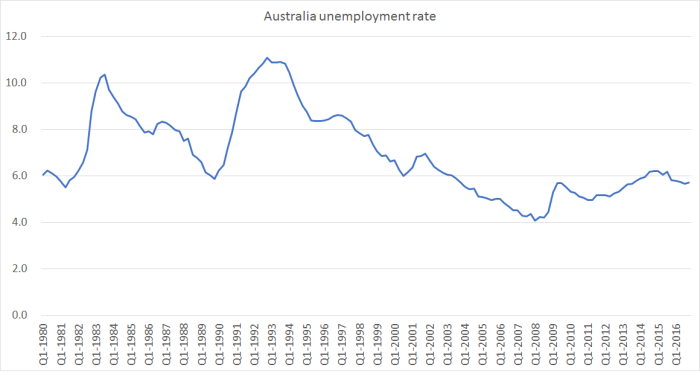

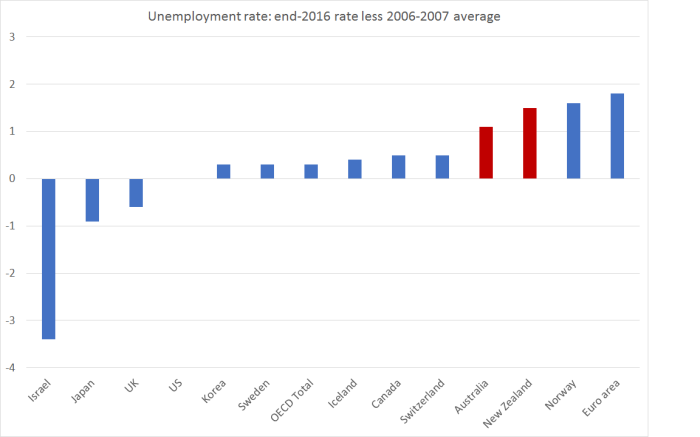

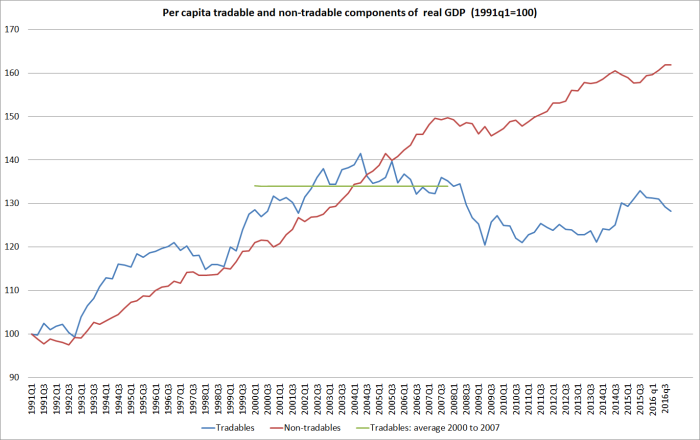

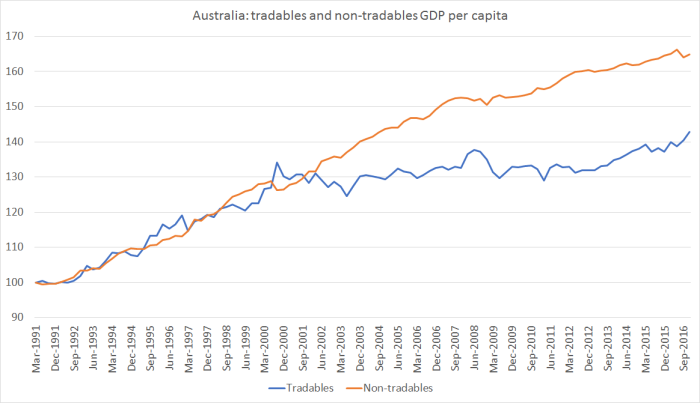

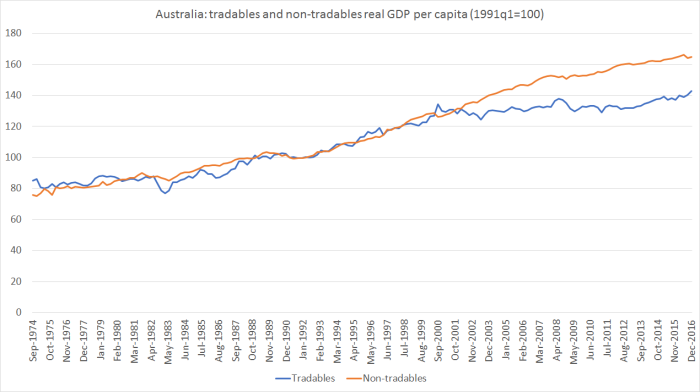

Recall that Auckland’s GDP per capita has been falling relative to that of the rest of the country for the last 15 years, and is quite low relative to that in the rest of the country when compared with other main cities in other advanced countries. Not only hasn’t Auckland outperformed, it appears to have quite badly underperformed. One could throw into the mix another point I’ve made previously: there is no major outward-oriented industry (exporting or import-competing) based in Auckland. It has the feel of a disproportionately non-tradables economy, servicing (a) the rest of the country, and (b) the physical needs of its own policy-driven growth.

How does the Initiative respond to this point?

However, a recent report highlights how standard measures can understate urban productivity differentials and estimates that Auckland’s firms have labour productivity 13.5% higher than firms in other urban areas.

This is, frankly, rather naughty. The Motu study in question produces revised estimates of labour productivity in Auckland relative to the rest of the country that are not dissimilar to the estimates of the ratio of nominal GDP per capita in Auckland relative to the rest of the country. No one has questioned that GDP per capita in Auckland is higher than that, on average, in the rest of New Zealand. But, by international standards, the margin is quite small. And, more importantly for this debate, the margin has been shrinking, even though the theoretical literature the Initiative seeks to rely on suggests it should have been widening. More people, from increasingly diverse places, generating more ideas, and as a result selling more stuff here and abroad, and investing to support those sales prospects. But it just hasn’t been happening. Instead, immigration policy has been putting more and more people in a place that doesn’t seem to have been producing the expected returns. And we know that New Zealanders, who presumably are best-placed to assess opportunities and prospects here, have (net) been leaving Auckland.

Frankly I was a bit surprised the Initiative didn’t have a more effective response to these indicators of Auckland’s underperformance and the troubling questions they appear to raise about the economics of New Zealand’s immigration programme.

The next section in the chapter is headed “Macro impact and how we measure it”. As they note

As a measure of living standards, GDP is not without its faults, but it does indicate how much a nation can produce and, ultimately, consume. The effect of immigration on GDP can be difficult to disentangle. There is little contention GDP increases with more immigration – that countries produce more with more people is a no-brainer.

Of more interest to economists is GDP per capita – how much the pie is growing relative to the number of people taking slices.

I’d add that the impact on the GDP per capita of natives is, or should be, of particular interest when it comes to considering immigration policy.

There is a surprisingly limited empirical literature on this point. There is a variety of papers which set up (calibrate) models for how the authors think the economy works, add an immigration shock, and then – surprise surprise – find that the model produces much the answer one expects. Papers in this class cover the range of results. Some are set up in ways that produce gains to natives of recipient countries, through some of the sorts of channels Initiative authors cite. But others, allowing for say fixed natural resources or sluggishly adjusting capital stocks, find that emigration tends to benefit the natives left behind, and slightly dampen the prospects of those in the recipient countries (the modelling the Australian and New Zealand Productivity Commissions used a few years ago in their review of the trans-Tasman relationship worked that way). In the recent Australian Productivity Commission report on immigration, the modelling work assumed that productivity growth in Australia would be mildly adversely affected by continuing relatively large immigration inflows (there is a somewhat jaundiced, but not inaccurate, summary here).

But in terms of straightforward empirical analysis of effects on GDP per capita or productivity, there isn’t a large pool of relevant papers (and none at all focused on New Zealand, even though we’ve had one of the largest planned immigration programmes anywhere, over a long period of time).

The Initiative authors refers to two papers. The first they summarise thus

A study of 22 OECD countries from 1987 to 2009 found migrants are not just attracted to countries with higher prosperity, they also help bring it about.

That sounds promising. The actual results don’t quite match the promise.

The authors estimates four different version of their model. In each case, they show results for how GDP per capita respond to net migration, net migration responds to GDP per capita, and how the unemployment rate and net migration respond to each other.

Here is the impulse response function chart from the first version of the model

The solid line is the central estimate, and the dotted lines are the confidence bands.

There is a statistically significant response of GDP per capita to a change in the migration rate in the first year after the shock, but everything beyond that is (a) statistically insignificant, and (b) slightly negative – ie below the zero line. No one would be surprised by a positive effect in the first period, since in the short-term demand effects from unexpected immigration inflows will typically exceed the supply effects. But over the medium-term, there is no evidence here of a sustained boost to per capita income. The pictures from the other three versions of the model all look much the same.

Before moving on, I should briefly highlight two other points about this paper:

- it uses net migration, whereas most of the theoretical arguments for possible gains from immigration relate to inflows of non-natives (new ideas, new skills etc). For most countries, the difference isn’t that important, but for New Zealand it is very important.

- one of the key things the paper sets out to show is that immigration does not materially affect the unemployment rate. This is a point that the Initiative and I are at one on, and – for what it is worth – the results of the paper suggest, as we would expect, no statistically significant effect.

The Initiative then moves on to some recent empirical work (Number 8, October 2016) by several IMF staff researchers, which built on another recent paper, by Ortega and Peri, but focused only on advanced countries.

The study finds that a 1 percentage point increase in the share of migrants

in the adult population can raise GDP per capita by up to 2% in the longer run and that the benefits from immigration are broadly shared across the income distribution.

As it happens, I wrote about this paper , somewhat sceptically, when it was first released, in conjunction with the IMF’s World Economic Outlook, late last year.

Here is the summary version of why the results simply don’t ring true.

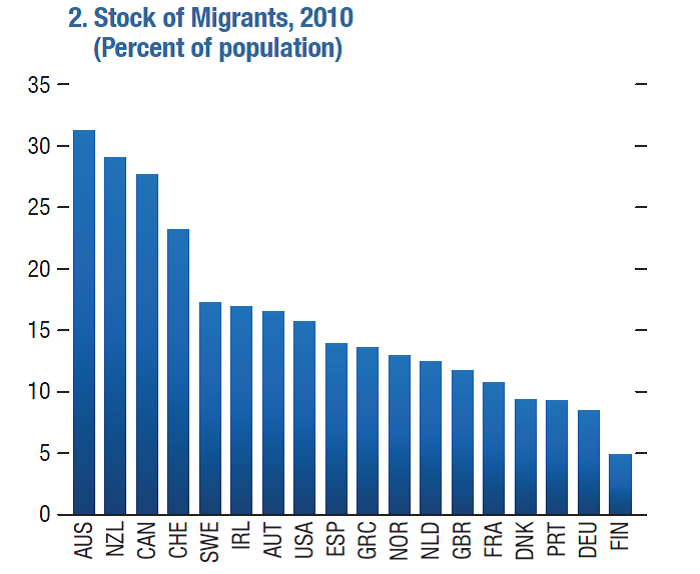

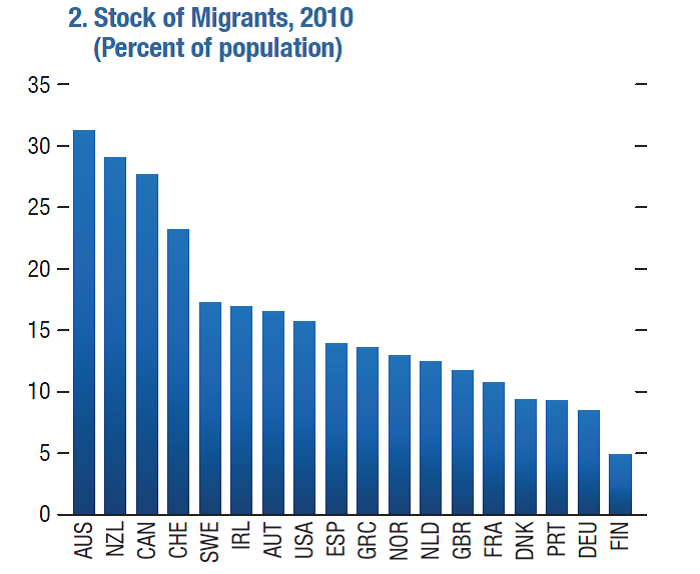

This chart is from the paper (here “migrants” is the foreign-born share of the adult population)

And this was my comment last year.

Think about France and Britain for a moment. Both of them in 2010 had migrant populations of just over 10 per cent of the (over 25) population. If this model was truly well-specified and catching something structural it seems to be saying that if 20 per cent of France’s population moved to Britain and 20 per cent of Britain’s population moved to France (which would give both countries migrant population shares similar to Australia’s), real GDP per capita in both countries would rise by around 40 per cent in the long term. Denmark and Finland could close most of the GDP per capita gap to oil-rich Norway simply by making the same sort of swap. It simply doesn’t ring true – and these for hypothetical migrations involving populations that are more educated, and more attuned to market economies and their institutions, than the typical migrant to advanced countries.

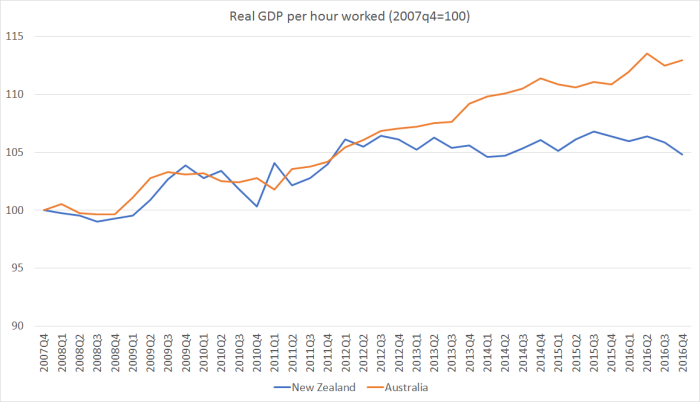

Or, we could turn it around, and think about New Zealand’s actual experience. Let’s say that the foreign-born share of New Zealand’s adult population increased by 10 percentage points since 1990 – I can’t quickly find the exact numbers, but it is likely to have been in that order of magnitude. If this model is correctly specificied – and recall that New Zealand is included in its sample – that should have given us a huge lift in productivity and GDP per capita, say by around 20 percentage points. In fact, of course, despite having had probably the largest non-citizen immigration programme of any of these countries in that period (Israel, for example, isn’t in their sample), our productivity (GDP per hour worked – the metric the IMF authors use) has slipped further behind that of other advanced countries. Yes, perhaps there were lots of other particularly bad offsetting policies undermining New Zealand’s prospects – but over this period international agencies, including both the IMF and OECD, repeatedly stated that they thought we had pretty good policies in place.

Of course, as I noted on Friday, my main interest is New Zealand. If immigration to and among other countries has been productivity-positive, that is something to celebrate, but there is little evidence that it has been so for New Zealand.

One could take the critique and questions a bit broader. For example, note how the gains arise in this study. It is from having a large (increased) share of foreign-born people in one’s population. But immigrants age, have children etc. Without a continuing inflow of non-citizen migrants, any initial boost to the foreign-born share will erode quite steadily over time.

The US offers an interesting case study. Around the time of World War One, about 15 per cent of the US population was foreign-born. Immigration restrictions imposed in the 1920s, and in place for the following forty years, saw the foreign-born share of the US population fall to around 5 per cent by around 1970. There was nothing comparable in other large migrant recipient countries (eg Australia, New Zealand, Canada). All else equal, if the IMF model was correctly-specificied, this huge reduction in the foreign-born share should have resulted in a substantial deterioration in the absolute and relative producitivity position of the United States. There is simply no evidence I’m aware of to support such a proposition (and, in fact, historical estimates suggest that the US had some of its strongest productivity growth in history during these decades).

In my earlier write-up of the IMF paper I noted that

There are other reasons to be skeptical of the results in this IMF paper. Among them is that there is a fairly strong relationship between the economic performance of countries today and the performance of those countries a long time ago. GDP per capita in 1910 was a pretty good predictor of a country’s relative GDP per capita ranking in 2010, suggesting reason to doubt that the current migrant share of population can be a big part of explaining the current level of GDP per capita (and some of the bigger outliers over the last 100 years have been low immigration Korea and Japan and high immigration New Zealand). In fact, I’ve pointed readers previously to robust papers suggesting that much about a country’s economic performance today can be explained by its relative performance 3000 year ago. How plausible is it that so much of today’s differences in level of GDP per capita among advanced countries can be explained simply by the current migrant share of the population?

If this is the strongest empirical support advocates of New Zealand’s approach to immigration can adduce, those who have been inclined simply to go along should surely be rethinking their unquestioning support for the policy approach – whatever merits it may or may not have for some other countries. I’m aware of a tendency for New Zealand Initiative people to think that the onus of proof isn’t, or shouldn’t, be on them, so obvious and “morally right” is the case for immigration. Quite where the burden of proof lies is probably more a political one than an economic one, but one might hope that the advocates could produce more evidence, or sustained analysis of the New Zealand case, than is evident in the New Zealand Initiative’s economics chapter. Especially when the policy approach they support has been tried for more than 25 years, and when even they concede some puzzles about New Zealand’s economic performance in that time.

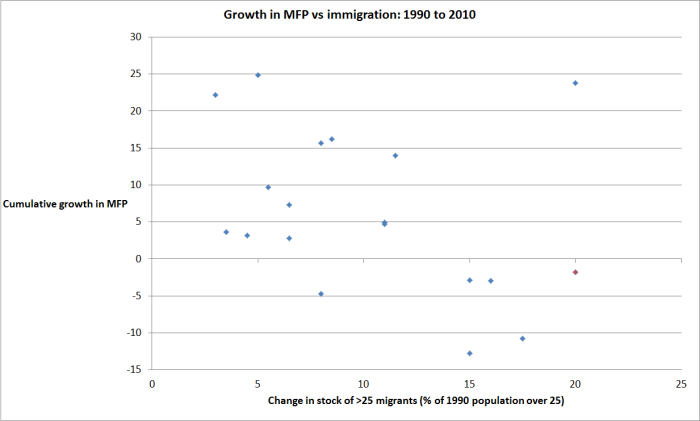

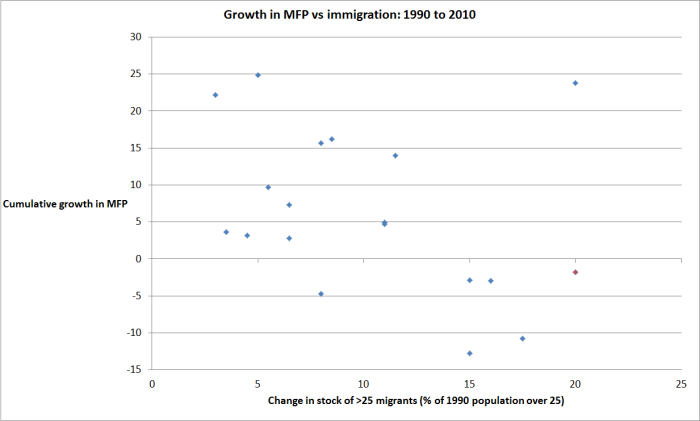

The authors of the IMF paper, and the earlier Ortega and Peri, paper, hypothesise that the gains from immigration come largely through a total factor productivity (TFP) channel. Although they never explicitly say so, The Initiative seem to share this perspective, with all their talk of ideas, innovation, alternative perspectives etc. The IMF researchers didn’t test the connection between immigration and TFP. But in my earlier post I included this chart, using the same foreign-born population share data the IMF did.

If anything, over the period they looked at, the relationship was negative – a larger increase in the foreign-born population share was associated with weaker TFP/MFP growth. New Zealand is the red dot in the chart. The outlier – in the top right hand corner – was Ireland, which looks more positive for the IMF/Initiative story, except that as I also showed in that earlier post, it is quite clear that the surge of migrants into Ireland came several years after the surge in TFP growth.

And, on the topic of TFP growth, in a post last week I illustrated again just how weak New Zealand’s TFP growth has been relative to that in other advanced economies. Surely, serious think-tank advocates of New Zealand’s large scale non-citizen immigration policy would want to engage with this sort of record, and the apparent inconsistency with the connections they have hypothesised?

Sadly, simply ignoring the actual record in New Zealand seems to be par for course in the economic chapter of the Initiative’s report.

To their credit, they devote a couple of pages of the report to my hypothesis around the contribution of immigration policy to New Zealand’s longer-term economic underperformance (pp 39 and 40 for anyone interested). As they note, I have argued that

- “given New Zealand’s continued heavy dependence on natural resource based exports, New Zealand might not be a natural place to locate many more people, while still generating really high incomes for them all”, and that

- high levels of non-citizen immigration have helpd explain persistently high real interest and exchange rates, in turn deterring business investment, especially that in the tradables sector, and thus tending to undermine productivity growth.

But they don’t really know what to do with these ideas, and so end up largely ignoring them. There is simply nothing more, in this section or in the rest of the report, on the issues around a natural resource based economy, that is very distant for major markets/suppliers/networks etc. New Zealand may have many things in common with other advanced economies, but this is one probably very important difference.

And when it comes to New Zealand’s dismal long-term productivity record, the limit of their comment is this

New Zealand productivity has been less than stellar for a long time – a concern to many economists and policymakers.

And that’s it. There is no attempt at all to engage with the data, or to tell some alternative story of economic management and prospects over the last 25 years or so, in which for example, non-citizen immigration has played a more favourable role.

There is a little bit more on real interest rates – why they’ve been so persistently high relative to the rest of the world.

The hypothesis also cannot fully explain why the real interest rate has not converged to the rest of the world. Reddell says competing theories explaining the high real interest rate, such as a risk premium associated with New Zealand investment, do not fit with the evidence either, in particular with the persistent strength of the real exchange rate. He contends that the only explanation currently on offer is that the repeated shocks to domestic demand – not fully recognised in advance by market participants – must have been a big part of the story.

Clearly, the Initiative don’t find my story persuasive, but there is simply no attempt to explain why, or to pose a credible alternative hypothesis for one of the most striking features of New Zealand macro data in recent decades.

The best they seem able to come up with is to point out that any sustained demand pressures will tend to put upward pressure on real interest rates. And that is quite correct of course. An economy with very strong productivity growth, and the associated investment in support of it and consumption in anticipation of the future income gains, will tend to have high real interest rates (relative to those abroad). And no one much will regard that as problematic – rather it is a mark of the success of the economy.

But that hasn’t been the New Zealand story. Business investment has been quite low as a share of GDP (especially given our population growth) and productivity growth (labour or total factor) has been low. There is little, or nothing, to suggest that the high relative interest rates we’ve experienced in New Zealand over the last 25 years have been a desirable market-led phenomenon. They look anomalous not just relative to other countries, but also relative to our own underwhelming economic performance.

Here is the Initiative’s attempt to fend off my analysis

The concerns raised by Reddell would apply more broadly than just on immigration. For example, tourists are foreigners who come to New Zealand, purchase our currency and goods, and use infrastructure (they require accommodation, drive on the roads, may require police assistance, add waste to landfills. etc.). Hence, tourism also puts pressure on the real interest rate and real exchange rate.

As I’ve already noted, any persistent demand pressure – whether from exports or the domestic economy – will, all else equal, tend to put upward pressure on local interest rates.

But except for population-driven pressures (in a country with a modest savings rate) we just haven’t had such pressures. As I noted just before, business investment has been lower than we might have hoped, exports as a share of GDP have been sideways or backwards, and the consumption share of GDP has been flat for decades. What hasn’t been flat has been the population, and particularly the foreign-born population, the direct consequence of government immigration policy. Take their tourism example. SNZ has data on the average daily stock of foreign travellers in New Zealand(boosting domestic demand) and the average stock of New Zealand travellers abroad (easing domestic demand), going back to 1999. There are more foreign travellers here than New Zealanders abroad, on average, but the numbers aren’t large. In 1999, there were on the average day 16000 more foreign travellers here than New Zealanders abroad. Last year, that number was 54000. 38000 (net) more travellers here is a helpful addition to net exports, and some pressure on demand. But

- the overall export share of GDP is less now than it was in 1999

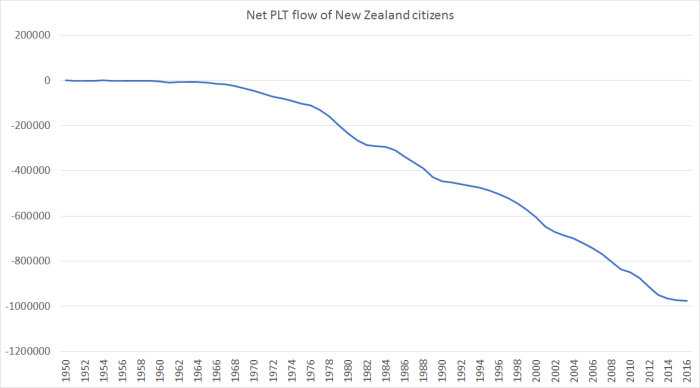

- from 1999 to 2016, there was a net inflow of 759000 non-citizen migrants to New Zealand.

That is both a very large number, and a direct government economic policy choice. It has had consequences, and there seems a reasonable prima facie case, which the New Zealand Initiative has not attempted to seriously rebut, that that government-controlled influx has not been economically beneficial to New Zealanders as a whole.

This post has already got rather long, so just two final thoughts.

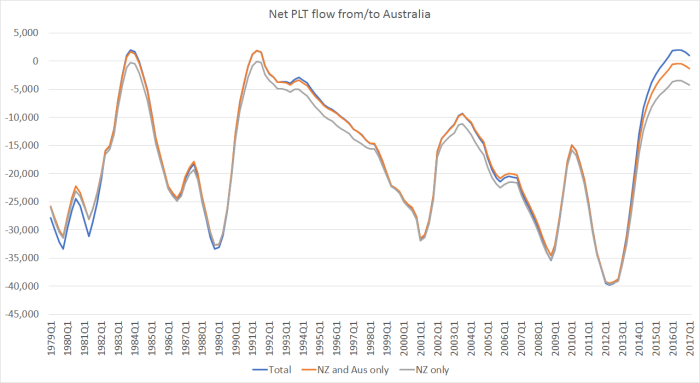

First, it is striking how little attention the Initiative gives to the large sustained outflow of New Zealanders over recent decades. That outflow is certainly at a low ebb at the moment, but there seems little reason to assume that the exodus has come to any sort of permanent end – as even the Initiative recognises, our productivity performance languishes. Whatever one thinks of immigration policy in the abstract, surely it is a somewhat relevant consideration to look at what New Zealanders themselves are doing – people best placed to assess opportunities and prospects here? There is, among some policymakers, a weird approach to this issue, in which immigration policy is substantially about replacing those who leave. I don’t think the Initiative subscribes to that silliness, but neither does it call it out. When individuals are making rational choices to move – to leave New Zealand – the burden of proof should really be on those who want the government to try to second-guess those judgements and choices. When people left Ireland, Italy, Sweden or wherever for the US in the 19th century, it benefited those who left and those who stayed. It would have daft for the authorities in those places to have responded “woe is me, we need to find some poorer people from other places to bring in to replace those who’ve left”. A quite different approach would be to respect and respond to the market signals – movements of their own people – and try to fix up their own economies in ways that might make it no longer attractive for their own people to leave. It would have been a much better lesson for the New Zealand authorities to take. Residents of Taihape and Invercargill should be grateful governments didn’t/couldn’t respond to outflows of people from those towns by suggesting a presssing need to get other people from elsewhere in the world to move to Taihape and Invercargill, even though the economic opportunities had moved on from those places.

And second, in the IMF paper that the Initiative cite there are references to a new paper by various Harvard researchers on the economic effects of diversity (so recent that the references have been added since the version of the IMF piece that I commented on last year). The authors note that typically in studies to date “the negative effects of diversity seem to dominate empirically”. In this paper, they find more positive results, but they also look at what sort of diversity might produce benefits (p 26)

we extend our index of birthplace diversity and account for cultural and economic distance between immigrants and natives. The productive effects of birthplace diversity appear to be largest for immigrants originating from richer countries and from countries at intermediate levels of cultural proximity.

and

This suggests that a combination of culturally closer immigrants and richer origins (potentially a proxy for higher skills) can be particularly valuable.

If this model is robust, then it is perhaps unfortunate for the economic case for the immigration programme that very little of New Zealand’s immigration is from countries richer than our own, and most of it isn’t from countries with close or intermediate levels of “cultural proximity”. By contrast – and uncomfortable as it is to point it out again – all New Zealand’s immigration in the mid 19th century was from countries richer than us. As such, there is little doubt that if lifted economic performance and productivity for all New Zealanders. Whether the results are robust is something for others to look at, but it is the sort of specific results, that recognise that some immigration can be beneficial, but not all needs to be – it depends on various things, including time, place, and people – that the New Zealand Initiative should be engaging with rather than merrily asserting, with no New Zealand specific evidence – that the gains to natives are there simply because people have come among us from another country, any country.

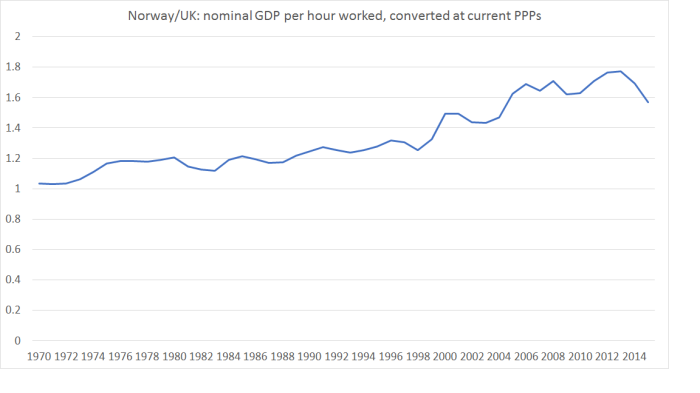

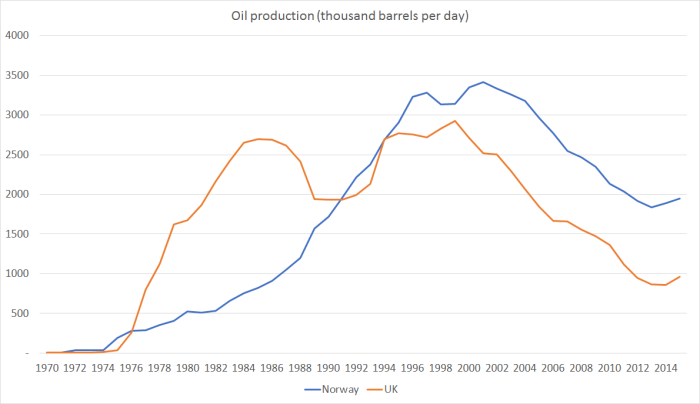

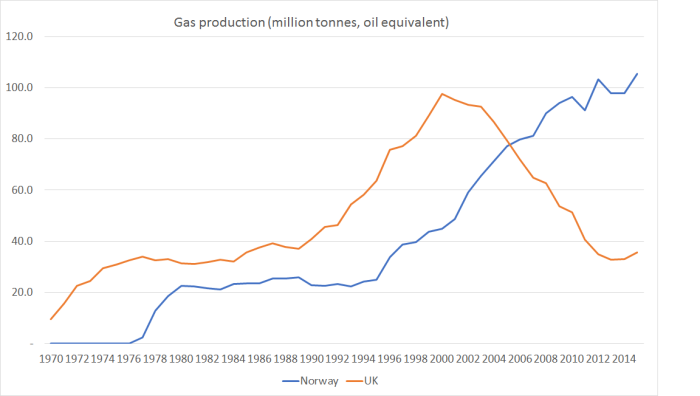

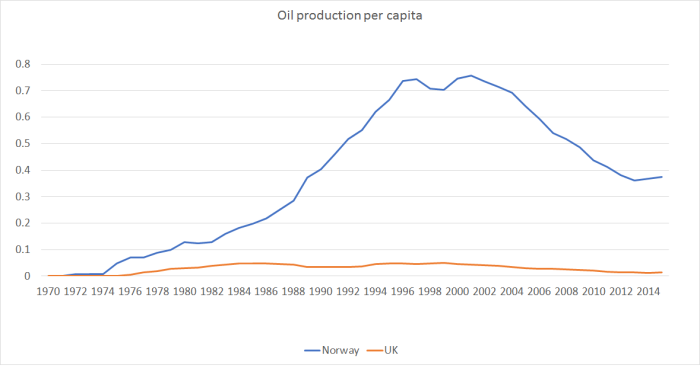

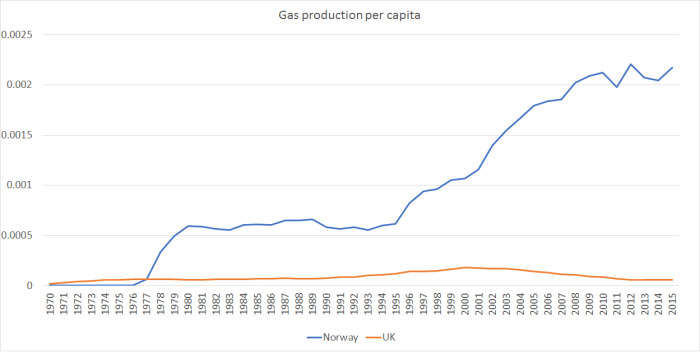

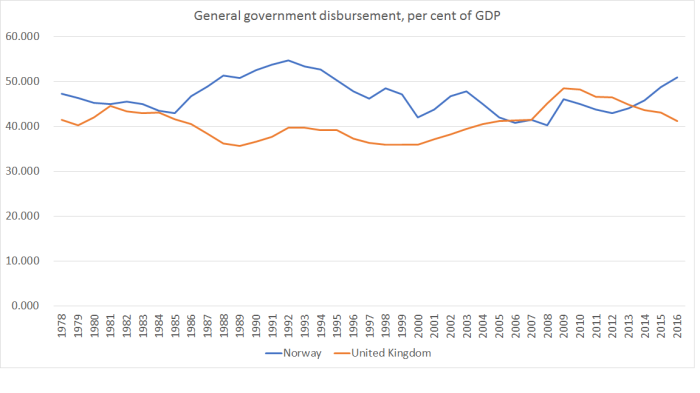

These days, by contrast, GDP per hour worked in Norway is around 60 per cent higher than that in the UK (which is in turn quite a bit higher than New Zealand’s). Norway has among the very highest material living standards of OECD countries, and the UK is still in the middle of the pack.

These days, by contrast, GDP per hour worked in Norway is around 60 per cent higher than that in the UK (which is in turn quite a bit higher than New Zealand’s). Norway has among the very highest material living standards of OECD countries, and the UK is still in the middle of the pack.

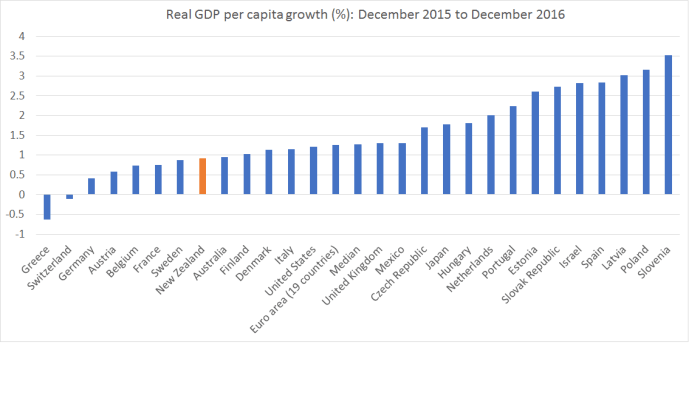

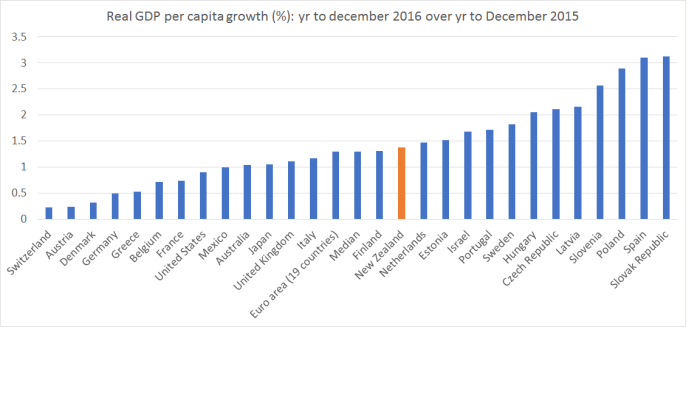

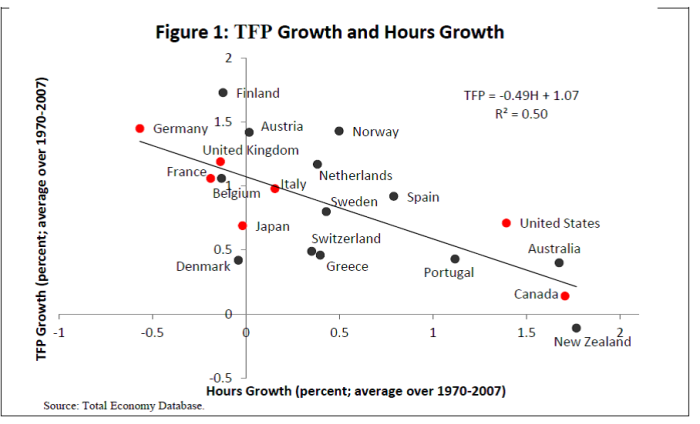

Over this period on this measure, we weren’t the worst, but we weren’t far off the worst. A lot of the former eastern-bloc countries, now given the opportunity to catch-up with the West, are bunched towards the left of the chart.

Over this period on this measure, we weren’t the worst, but we weren’t far off the worst. A lot of the former eastern-bloc countries, now given the opportunity to catch-up with the West, are bunched towards the left of the chart. And New Zealand relative to the median of the G7 countries, and to the median of the former eastern-bloc countries. Recall, after all, that the narrative of economic reform in New Zealand had also been to allow us to catch up again with the richer advanced countries.

And New Zealand relative to the median of the G7 countries, and to the median of the former eastern-bloc countries. Recall, after all, that the narrative of economic reform in New Zealand had also been to allow us to catch up again with the richer advanced countries. Not an altogether pretty picture.

Not an altogether pretty picture.

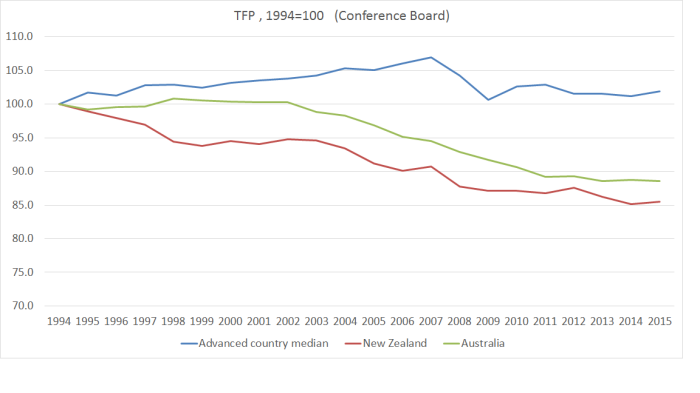

The gap between New Zealand’s cumulative TFP growth and that of the other advanced economies isn’t as large as that shown on the Conference Board data (second chart above). Then again, since the OECD data doesn’t include the catching-up eastern Europeans that shouldn’t be a surprise. But what is more striking is that until 2003 we were more or less matching the other OECD countries in this sample.

The gap between New Zealand’s cumulative TFP growth and that of the other advanced economies isn’t as large as that shown on the Conference Board data (second chart above). Then again, since the OECD data doesn’t include the catching-up eastern Europeans that shouldn’t be a surprise. But what is more striking is that until 2003 we were more or less matching the other OECD countries in this sample. In the end, perhaps the pictures aren’t really that dissimilar after all. We’ve done badly relative to other traditional advanced countries and, if anything, on this measure too, the last decade or so is looking relatively worse. In other words, if there was some convergence of growth rates, it looks to have been mostly only because TFP growth in the east European countries (in the TED sample but not in the OECD’s) slowed up so very markedly (as you can see in the third chart above). That might be unfortunate for them – and some combination of policy limitations, and substantial convergence already having occurred in some countries – but doesn’t put New Zealand’s underperformance in any better light.

In the end, perhaps the pictures aren’t really that dissimilar after all. We’ve done badly relative to other traditional advanced countries and, if anything, on this measure too, the last decade or so is looking relatively worse. In other words, if there was some convergence of growth rates, it looks to have been mostly only because TFP growth in the east European countries (in the TED sample but not in the OECD’s) slowed up so very markedly (as you can see in the third chart above). That might be unfortunate for them – and some combination of policy limitations, and substantial convergence already having occurred in some countries – but doesn’t put New Zealand’s underperformance in any better light.